A comparative study of classic 1960s manga by Tatsumi Yoshihiro and Tsuge Yoshiharu by Tom Gill, Meiji Gakuin University.

(Note: Japanese names are given in Japanese order, surname followed by personal name. The author would like to acknowledge the kind assistance of Bill Randall who read an earlier version of this paper and made many valuable comments on it.)

Introduction

Urban Japan in the 1960s was an exciting but bewildering place. World-beating levels of economic growth were accompanied by huge demographic upheavals. From 1950 to 1970, the population of Japan grew by roughly one million people per year. At the same time, the rural population came funneling into the cities at the rate of 1% of the total population every year [1]. Tokyo and Osaka became two of the most overpopulated and polluted cities in the world. One aspect of the massive shift from rural to urban lifestyles was that children started changing from being an economic asset (manpower in the fields or fishing boats who would one day inherit the business and look after their aging parents) to being a liability, as they had to be educated to ever higher levels and became increasingly unlikely to live with their parents in the latter’s old age as farmhouses gave way to cramped apartments. The cost of education was rising as an ever-expanding population of high-school graduates competed for ever more highly prized places at elite public universities and even the also-rans would increasingly expect their parents to pay for four years at a less prestigious private school.

One side effect of all this was a huge increase in the number of abortions. During the 1960s even official government statistics found that there were 400 to 700 abortions for every 1,000 live births [2]. Under-reporting of abortions means that the true figure was probably between twice and three times that level (Norgren 2007: 7). The Japanese government refused to license the contraceptive pill; it was not to legalize it for several more decades. Poorer women were often forced to go to back street abortionists or do it themselves. Abandoned fetuses became one of the sad little byproducts of Japan’s frenetic urbanization and industrialization.

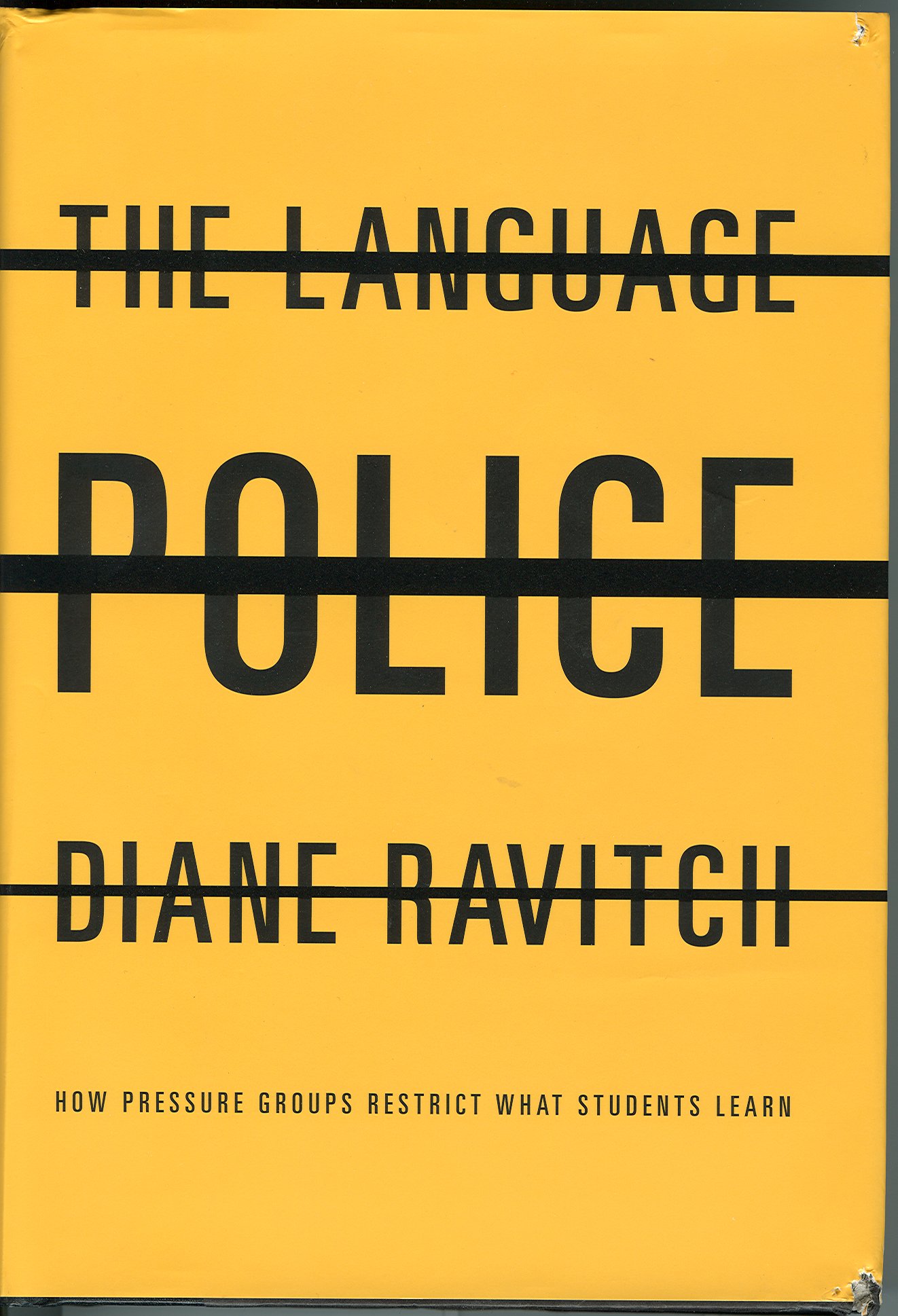

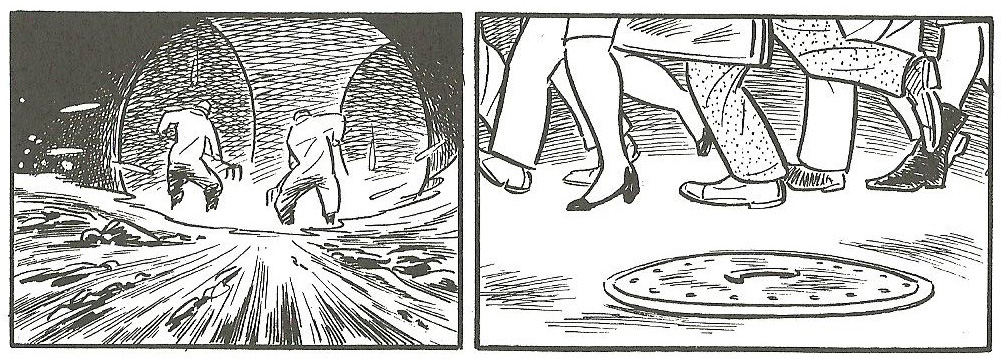

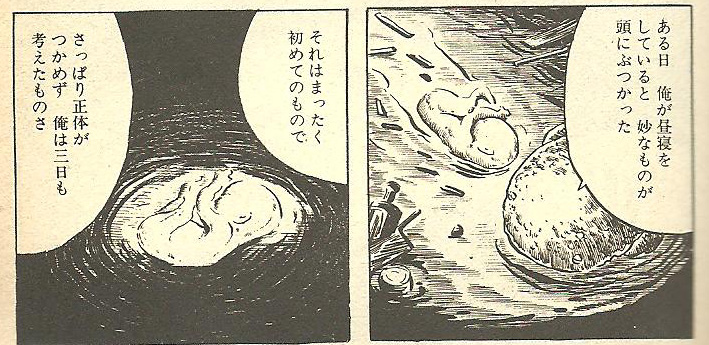

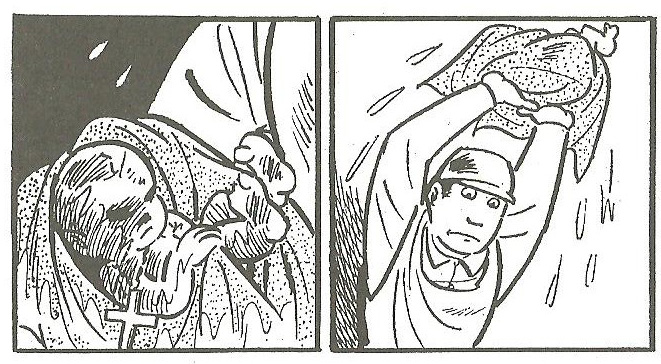

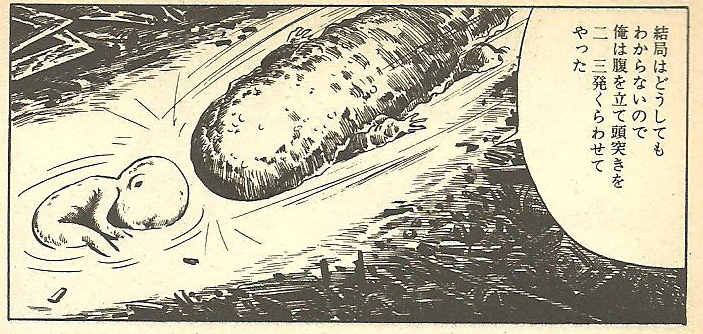

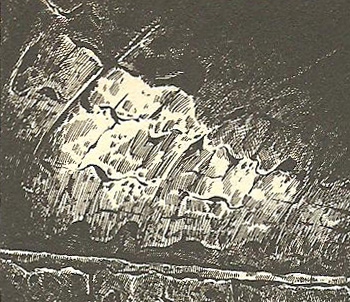

Fig. 1 Images of fetuses in Tsuge Yoshiharu’s ‘Sanshôuo’ (p. 6, frames 3 and 4; left) and Tatsumi Yoshihiro’s ‘Sewer’ (p. 2, frames 6 and 7; right). Tsuge reads right to left; Tatsumi left to right.

It was against this backdrop that the two works I wish to focus on here were written. They are both short manga, written by intense young men whose names were closely associated with the gekiga style – literally, “dramatic pictures.” Gekiga artists replaced cute tales for children with hard boiled stories based on real life situations. In these two cases the real life situation was the abandonment of an aborted fetus in the sewers under some great city. In ‘Sewer’ by Tatsumi Yoshihiro (1969), a sewage worker finds a fetus while at work and later is obliged to throw away his own girlfriend’s fetus in the same place. In ‘Sanshôuo’ (Salamander) by Tsuge Yoshiharu (1967), a salamander swimming in the sewers beneath a great city encounters a floating fetus and puzzles over its meaning. In this paper, I will compare the way these two great manga artists make use of the same motif for very different artistic and political ends.

‘Sewer’ by Tatsumi Yoshihiro (1969; 8 pages)

Tatsumi Yoshihiro (born 1935, in Osaka) is widely credited with coining the word gekiga in 1957 [3]. His late ‘60s manga are typically short, brutal accounts of modern urban life in the Japanese working class or underclass. Many are now available in English thanks to the efforts of Japanese-American manga artist Adrian Tomine and the Drawn & Quarterly publishing house, which is now translating Tatsumi’s work at the rate of one volume per year [4]. ‘Sewer’ appears in The Push-man and other stories (Tatsumi 2005). In the Introduction, Tomine describes Tatsumi’s work as reading like “the direct expression of a personality that is keenly observant, deeply self critical, and constantly torn between sympathy and misanthropy.” The work in question is very much in character.

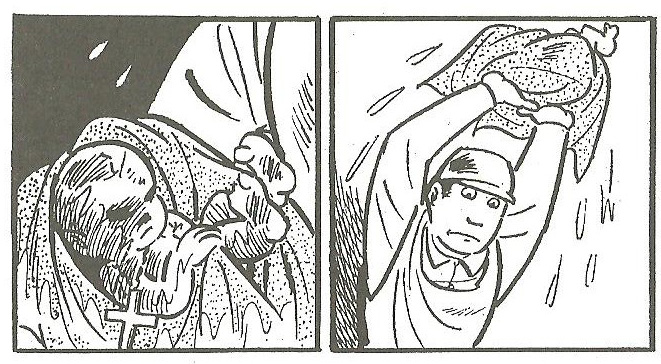

A young man, anonymous, dressed in overalls, gumboots and cap, is working in a massive underground sewer, using a three pronged hook to remove blockages. One day, something bumps against his leg. It is wrapped in a furoshiki, a Japanese kerchief used for carrying small bundles. It turns out to be a fetus, clearly recognizable and with a crucifix hanging from its neck. The young man’s face shows no expression. He raises the furoshiki above his head and is about to throw its back into the sewage when he is stopped by his boss. The boss removes the crucifix and then tosses the fetus back into the sewage without even bothering to put it back in its wrapping. He plans to sell the crucifix, which could be gold. After work, the two men take a shower. The boss, a tough old working class man, calls our hero ‘an odd one.’ Why should a young man like him want to work in the sewers? The young man says nothing. We sense his alienation as he walks home past busy streets in a great crowd of people.

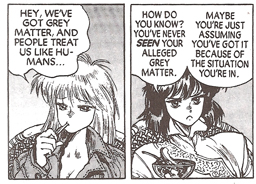

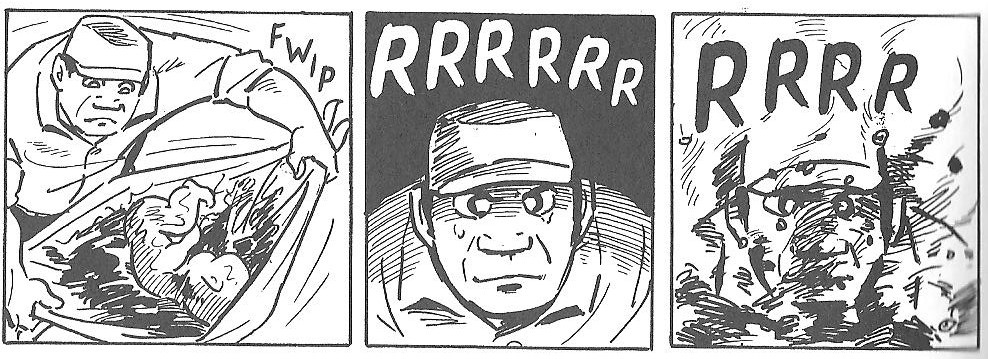

‘Home’ turns out to be his girlfriend’s apartment. She does sewing work at home, and has just finished sewing a wedding gown as he arrives. She is pregnant, and she tries the wedding gown on for size in a less than subtle hint that she thinks he should take responsibility and marry her. He responds by approaching her from behind, putting his hands on her breasts, and initiating sex. As usual, there is no expression on his face. A tap dripping into the dirty sink conveys the passing of time and the squalid nature of their surroundings and, by implication, their relationship. She accuses him of only wanting her for sex. His response is to take her to a disco, where they dance intensely to a large rock band. She starts to feel unwell (fig. 2 left) – a touch of morning sickness, perhaps. He breaks into a sweat and finally lets out a scream (fig. 2 right) – the only moment in the whole story when his face shows some kind of expression, and the only sound he makes in the whole story as well.

Fig. 2 Tatsumi, ‘The Sewer’ p. 5, frames 9, 10 (read left to right)

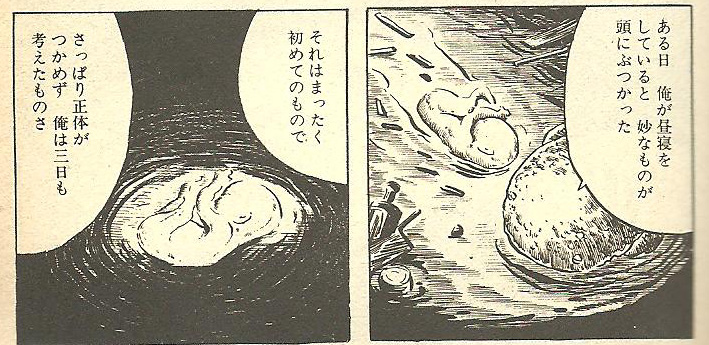

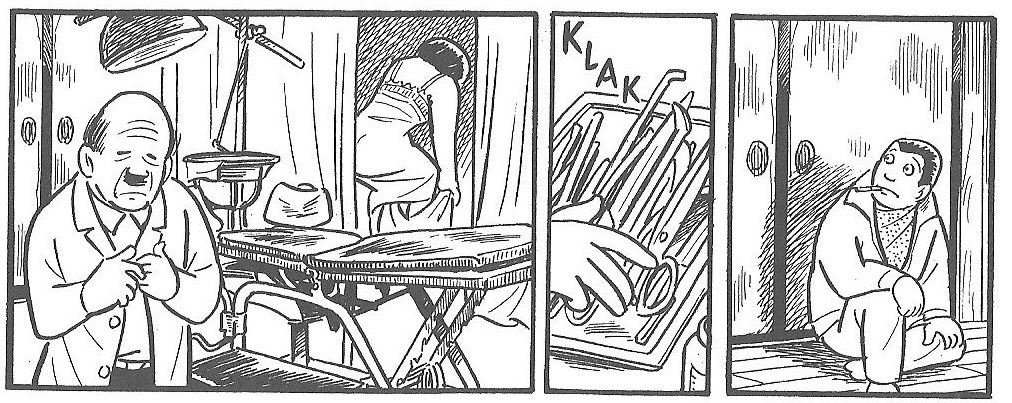

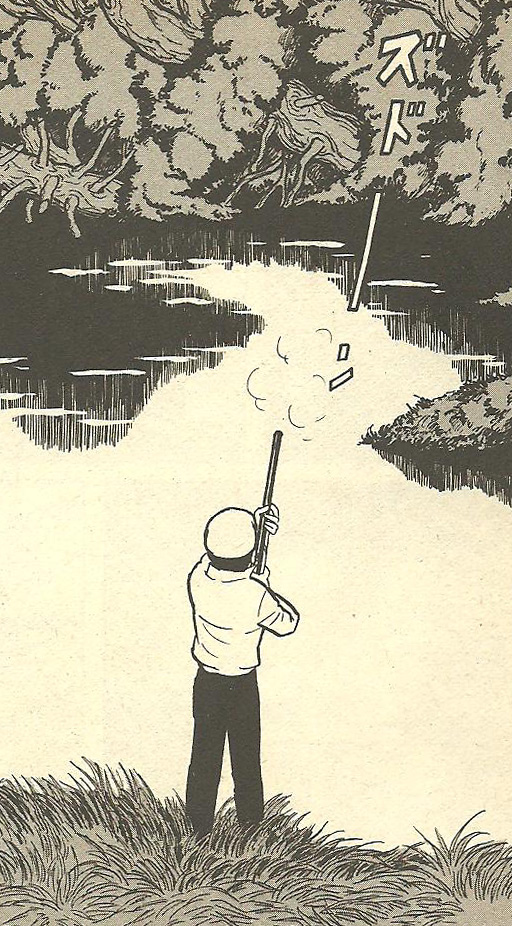

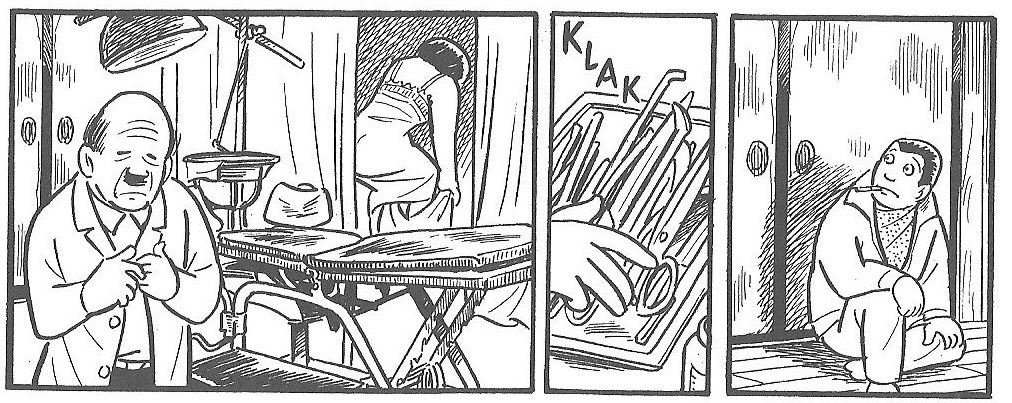

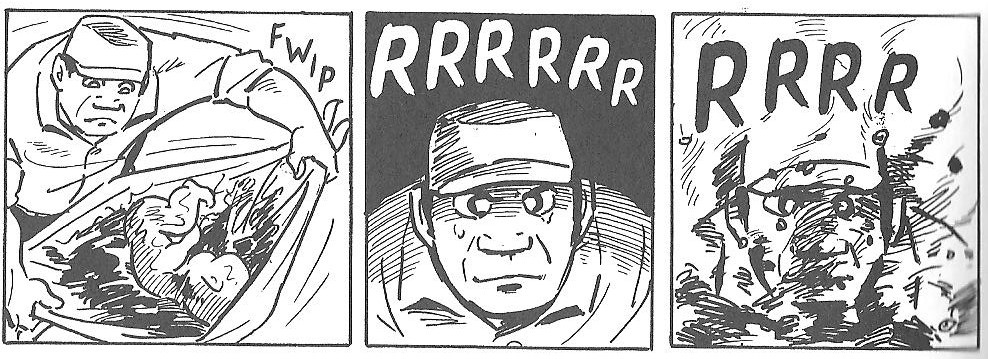

We next see them asking for directions in a rundown neighborhood, looking for a backstreet abortionist. While the job is being done, the camera stays with our hero outside the closed doors (fig. 3).

Fig. 3 Tatsumi, ‘The Sewer’, p.6 frames 6, 7, 8 (read left to right)

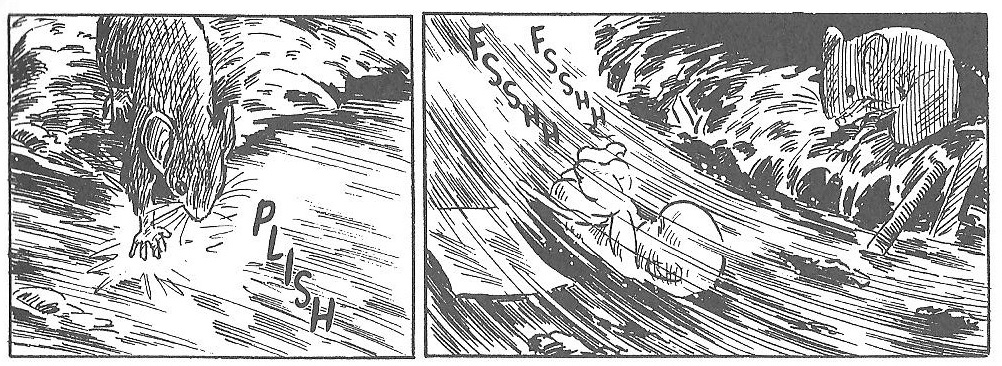

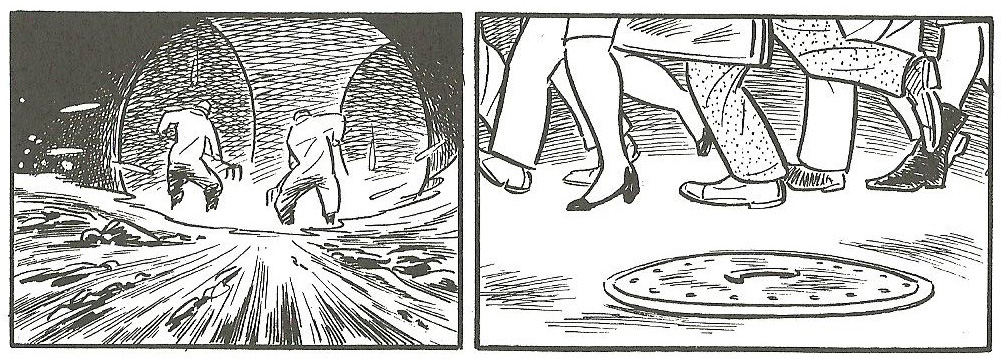

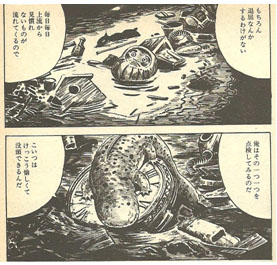

We never see the fetus, but the next day he arrives for work with his own little furoshiki. His boss complains that he is late and that the sewers are badly clogged up today. Our hero carefully places the furoshiki in the water and watches it float away, a slight reddening of his cheeks the only indication of shame or embarrassment. But the furoshiki is spotted by his boss who picks it up and opens it to see if there is any gold or silver with this fetus. As the crucifix on the previous fetus showed, it was not uncommon for women having back-street abortions to assuage their guilt feelings by putting small items of jewelry with the fetus. There is none, however, so he tosses it back into the sewage, the baby this time clearly visible as he has not bothered to tie up the furoshiki. Our hero, still expressionless, stands there dumbstruck. The boss tells him to get back to his work. They carry on (fig 4 left). The final frame shows a manhole cover, presumably just over where they are working, with the feet of half a dozen pedestrians going past it (fig. 4 right).

Fig. 4 Tatsumi, ‘The Sewer’, p. 8, final 2 frames (read left to right)

It is a chilling yarn, vividly recalling the Japanese proverb ‘kusai mono ni futa’ – if something smells, put a lid on it. The legs we see in the final frame are moving fast, looking purposeful, helping to keep the busy city running smoothly. Any little problems that may arise from that society are quietly disposed of in places where most people will never see them. The muted expressions of the characters accentuate the alienated atmosphere. This is true of all the characters – we never see more than a vestigial smile or a faintly downturned mouth on the face of the girlfriend, and often her face is turned away from us or concealed by hair; while the abortionist and the sewer boss are just phlegmatically getting on with business. But our hero is the extreme case. Not only is he blank faced almost throughout the story, looking innocent, at a loss, or resigned, but he is also mute. One inarticulate scream at a disco is the only sound he makes; no words escape his lips. His anonymity, expressionless face and silence express the inner repression needed to survive in the darker backwaters of modern industrial society. Note also that there is no interior narrative either: the thought bubble is one manga device that Tatsumi never uses in this story, or in many others from this period. Nor is there any use of explanatory text to tell you what is happening or about to happen. We are left with manga stripped down to its bare essentials: action with almost no explanation; images that have to explain themselves. This is the way most of the stories are told in Tatsumi’s 1969 collection, The Push Man and Other Stories, and it is interesting to see how characters’ inner thoughts start to be featured in the 1970 collection, Abandon the Old in Tokyo, and explanatory text in the 1971-2 volume, Good-Bye. For me, these textual explanations, though a handy narrative tool, dilute the alienated intensity of Tatsumi’s manga. (Tsuge also wrote many of his classic late 1960s manga without any use of thought bubbles or textual explanation, though ‘Sanshôuo’ is an exception in which Tsuge chooses to make the salamander think rather than speak.)

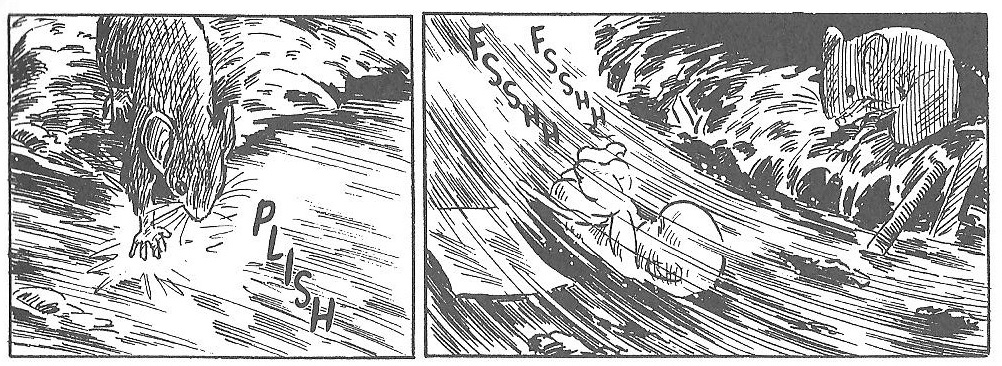

Tatsumi makes cinematic use of sound effects to generate atmosphere. Typical manga onomatopoeia conveys the sound of water dripping and splashing, the whirr of the girlfriend’s sewing machine, and the tiny metallic sound of the abortionist picking up his tools (fig. 3 center). When the couple go to the disco, every frame is bursting with noise – thumping drums, screaming guitars (fig. 2 left) – but the frames immediately before and after that episode are silent. And after the final splash of our hero’s baby being thrown back into the sewage, the rest – the men working amid the flowing sewage (fig. 4 left), the clattering footsteps of the crowd passing the manhole (fig. 4 right) – is silence.

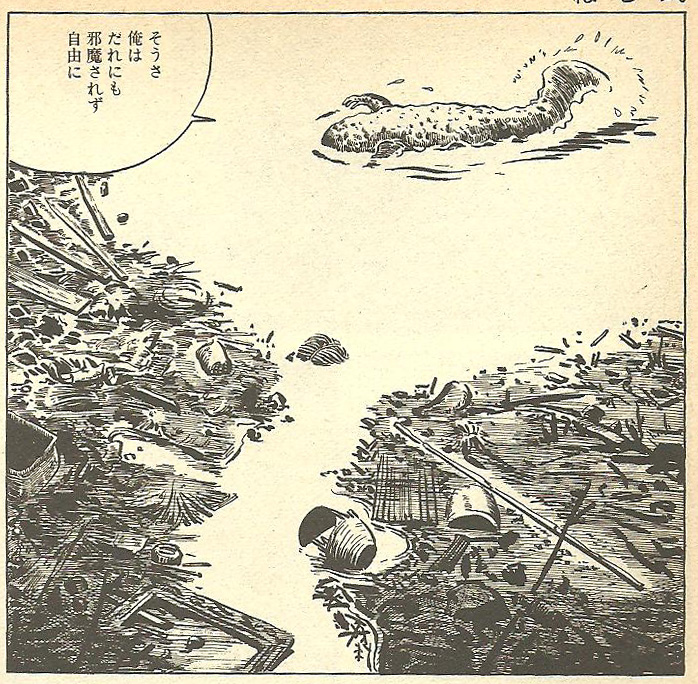

There is nothing fancy about Tatsumi’s frame sequencing. After a large opening frame introducing our hero and displaying the title of the story, the narrative proceeds pretty steadily at 9 to 12 frames a page, a succession of small frames with dark backgrounds contributing to the claustrophobic atmosphere of the story. There is almost no embellishment: for example, it is almost impossible to identify any other objects in the sewage besides the two fetuses. A few boxes and sticks, and a single rather disturbing little animal – a rabbit fetus? a deformed piglet? – on page 1 (fig. 5 left; detail right), are the only objects we see that are not essential to the plot.

Fig. 5 Tatsumi, ‘The Sewer’, p.1, frame 2 with detail

The fetuses themselves are depicted with a grim, stained realism. Twice Tatsumi briefly allows us to dream of a mystical or sentimental way out of this cruel little tale. When the first fetus is discovered it has the crucifix hanging from it and our hero raises it above his head still swaddled in its furoshiki. It is a surprising image, especially in a non-Christian society like Japan. For a moment we are reminded of the baby Moses, found drifting amid bulrushes, or of the baby Jesus wrapped in his swaddling clothes. In fact, as far as we know, our hero is raising the baby above his head only in order to hurl it further away from him and back into the river of sewage from which it came. Then, when our hero’s own aborted baby is found by his boss, the boss cradles it in his arms with a look of sadness on his face, and says “that’s a shame.” A moment later we realize that the boss is only sad because there is no valuable gold or silver in the furoshiki, and he casually tosses the fetus back into the sewage. This is nihilistic theatre of cruelty. There is no humor, hope, or any other redeeming feature to cheer our hearts at the end of the story.

‘Sanshôuo’ (Salamander) by Tsuge Yoshiharu (1967; 7 pages)

Born in Tokyo in 1937, Tsuge Yoshiharu scraped a living by drawing hard-boiled adventure yarns for pay libraries until 1965, when he was plucked from obscurity by Nagai Katsuichi, the legendary editor of Garo, the monthly alternative manga magazine which was already well on its way to becoming an essential element of the counter culture by the time Tsuge came on board. Although Tsuge is highly respected in Japan, and far better known than Tatsumi, he has not had the English-language exposure that Tatsumi is now enjoying. This manga of Tsuge’s, published in Garo in May 1967, has never been translated into English or any other language as far as I know [5].

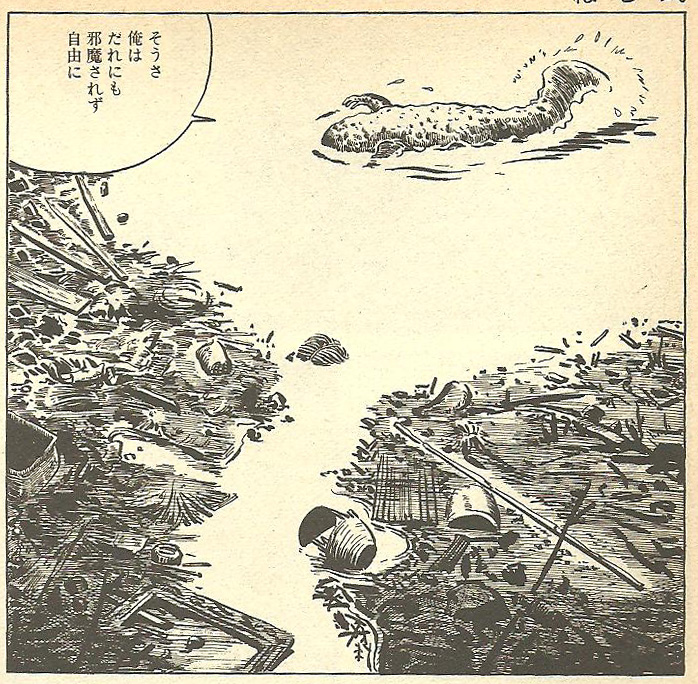

A salamander [6], depicted in exquisite anatomical detail, is seen swimming in the sewers beneath some great city. It reflects on its own being: it cannot remember how it got here, though it vaguely recollects some very distant hometown. It recalls how disgusted it was at first by the vile stench of the dead and rotting things floating in the sewer – “There were times when I vomited and had diarrhea at the same time.” Now however, he has quite got to like it – he is on his own, undisturbed, and enjoys exploring the variety of flotsam and jetsam floating around the labyrinth of sewers.

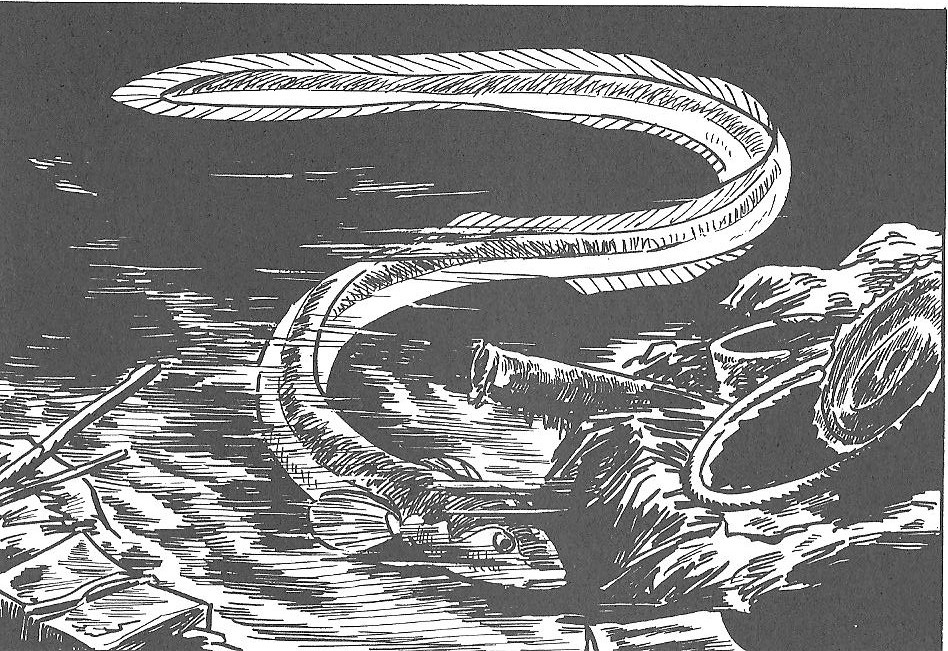

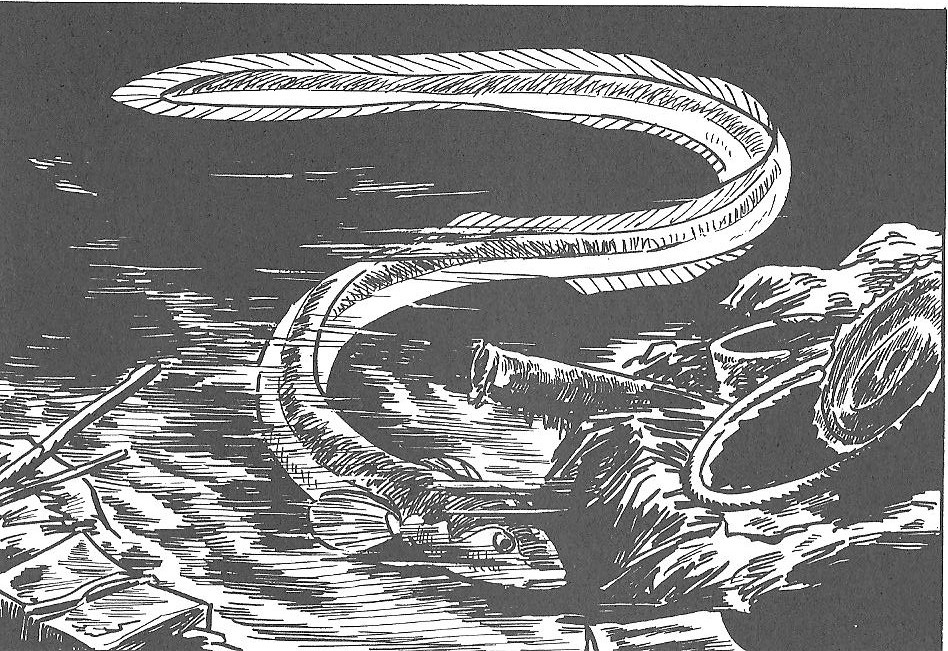

Fig. 6 Tsuge, ‘Sanshôuo’, p.7, frame 1.

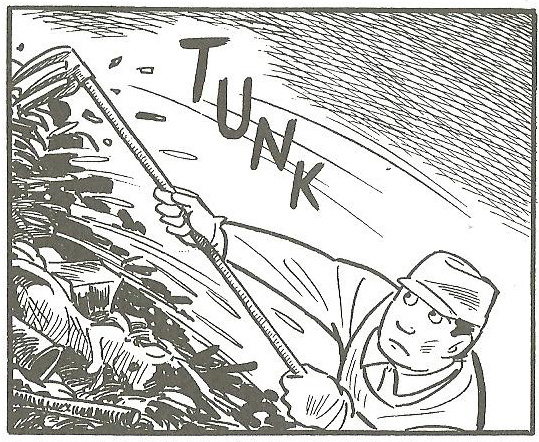

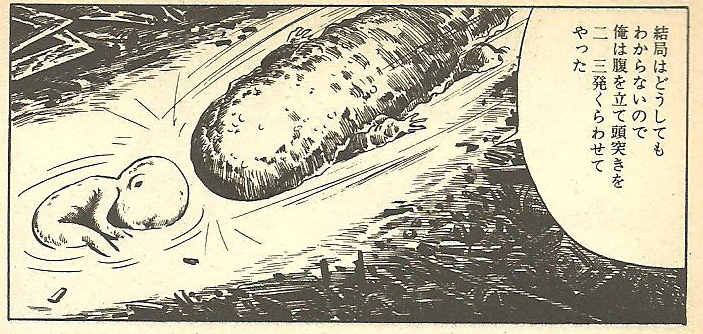

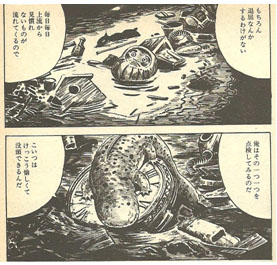

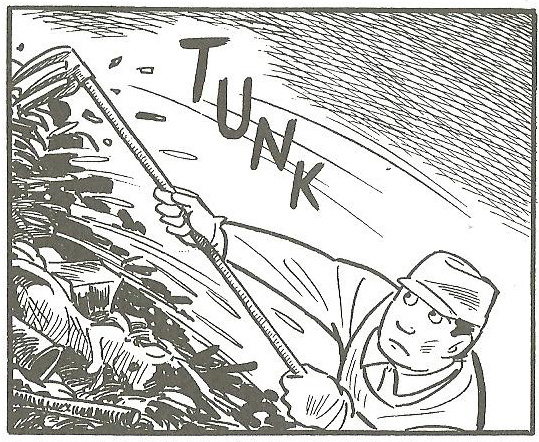

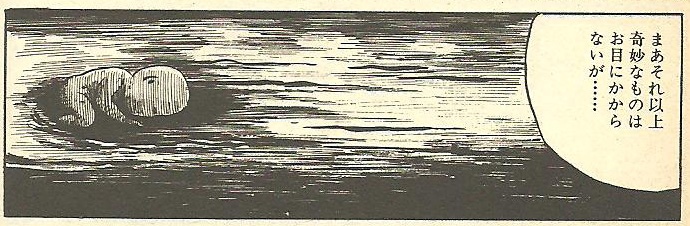

He recalls a recent incident (fig. 1 left, above). “One day while I was having my siesta, a strange thing came and bumped up against my head” (fig. 1, center left). “I’d never seen anything like it. I couldn’t imagine what it was. I thought about it for three whole days” (fig. 1 far left). “In the end I just couldn’t figure it out so I got irritated and gave it two or three butts with my head” (fig. 6). “Well… I’ve never seen anything as weird as that” (fig. 7). The picture tells us that the strange thing was a human fetus. It is not clear whether it is alive or dead. It is surrounded by an aura of light, drawn as if it were still in the womb (fig. 1 far left). The salamander’s head butts send it drifting on down the sewer, the aura of light changing to one of darkness (fig. 7).

Fig. 7 Tsuge, ‘Sanshôuo’, p.7, frame 2

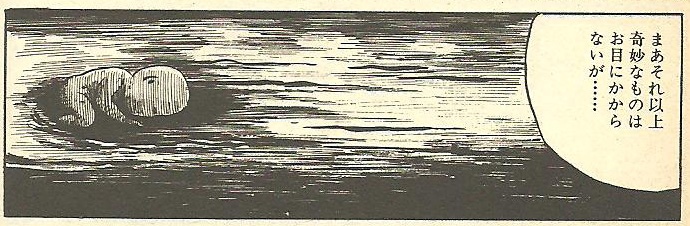

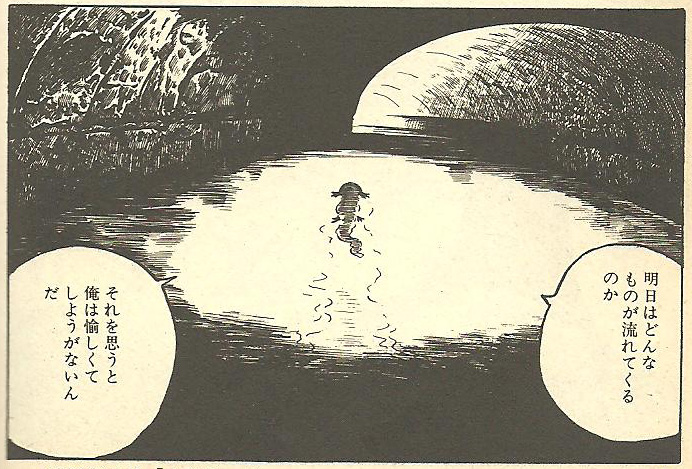

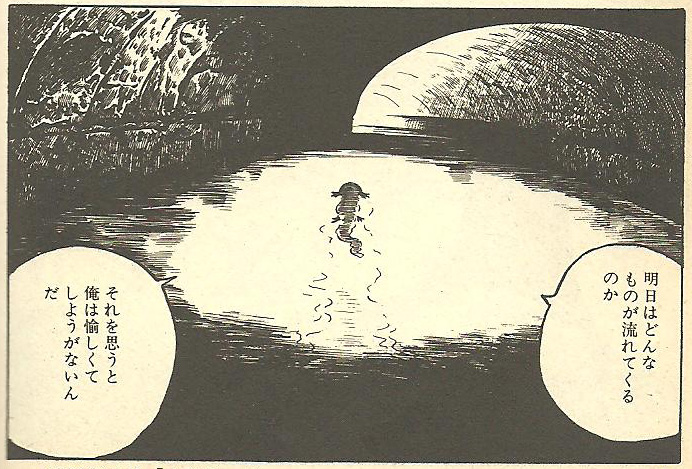

In the final frame (fig.8) we return to the present moment. The salamander finally swims into the distance, remarking “I wonder what will come floating my way tomorrow. Thinking about it brings me a feeling of incredible pleasure.”

Fig. 8 Tsuge, ‘Sanshôuo’, p. 7 frame 3 (final frame)

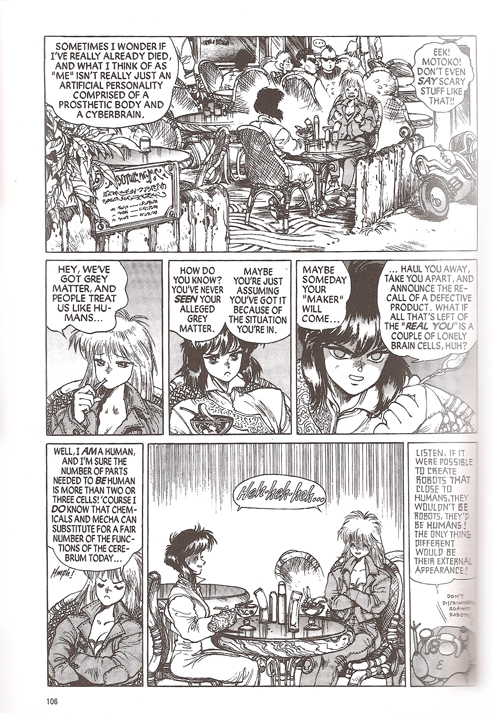

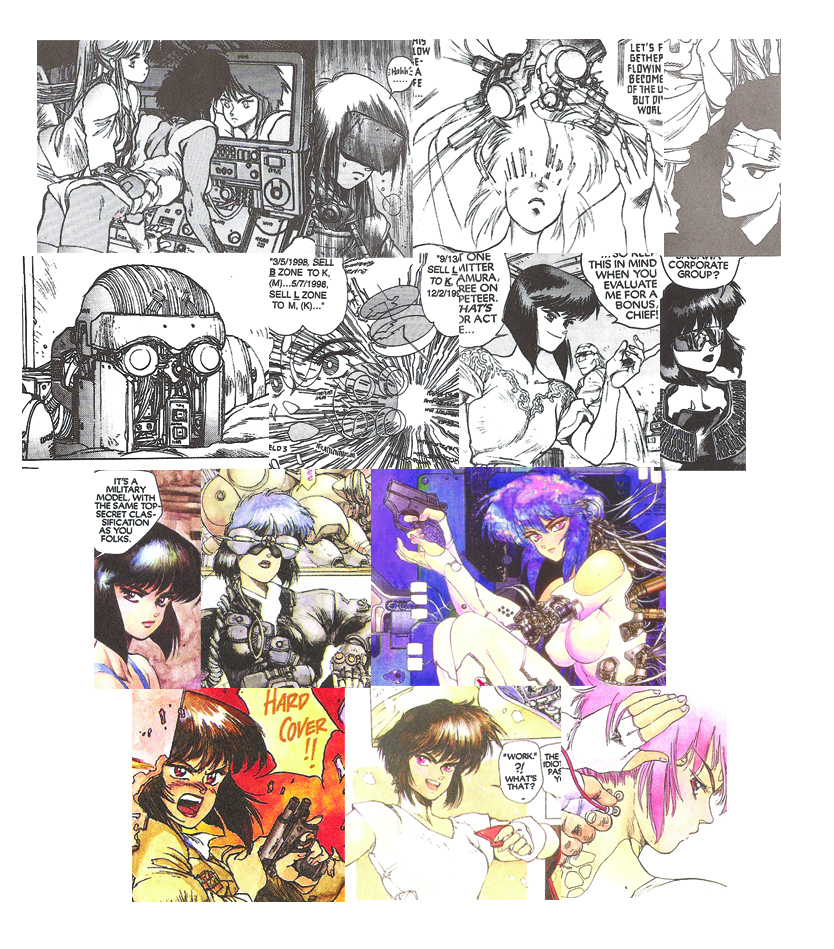

Where Tatsumi offers us brutal social realism, Tsuge is more of a symbolist. At one level, the sewers in his story are the real thing, with far more attention to depicting the detritus in them than we find in Tatsumi. But they are also teeming with symbols. In the haunting opening frame (fig. 9 left), the deformed brickwork on the sewer walls hints at sad or menacing masks (fig. 10, left), a mélange of random flotsam, looked at closely (fig. 10, right) hints at drowning arms (yellow ring), battleships (blue rings), a word in Roman letters, possibly “PEACE” or “TRACE” (green ring) and, intriguingly, a tiny image of a human figure, possibly Disney’s Snow White (red ring). The eddying water (fig. 9 left) hints at giant eyes and a nose, anticipating the emergence from the depths of the salamander. Among the items that float past the salamander during the story (some visible in fig. 9 right) are two large clocks, a bicycle wheel, a couple of crumpled books or magazines, sandals, a goat’s skull, a dead dog, bottles, tin cans, rubber gloves, a parasol, the giant eye from an optician’s shop sign, broken pots, a basket, bamboo sticks, a picture frame, a dharma doll, a birdhouse, a small animal (maybe a water rat, possibly alive), a toy car, and, rather worryingly, a gas mask.

Fig. 9 Tsuge, ‘Sanshôuo’ p.1 frame 1 (left), p. 6 frames 1, 2 (right)

Fig. 10 Tsuge, ‘Sanshôuo’ p. 1, details

Some of these images are used by Tsuge elsewhere [7]. Here they have an ominous effect. The broken clocks – both seem to have lost their hands – tell us that time has no meaning here. Perhaps, too, they recall the famous images of stopped clocks at Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Combined with the gas mask, they hint that perhaps some awful catastrophe has occurred. Maybe above the sewers, everyone is dead. The fetus may possibly recall the one that used to be on display, preserved in formaldehyde, at the Peace Museum in Nagasaki. The cheerful disposition of the salamander takes on a ghastly irony here. We see the end of religion (dharma doll; it has both eyes painted in indicating a wish fulfilled, yet looks terrified), science (clocks, optician’s sign), industry (toy car), art (picture frame), literature (books and magazines), and even nature (dead animals and skulls). It seems the salamander is frolicking amid a compendium of life now destroyed.

At another level, Tsuge’s sewer could be a birth canal. Certainly when the fetus comes bobbing along we cannot escape that implication. Then the story takes on an even more brutal misanthropy. Human life springs not from a pure wellspring but from a putrid sewer. When the salamander head-butts the fetus downstream, we are left to contemplate the horrible possibility that it is actually going to be born when it emerges from the sewer. If the sewer is a birth canal, the salamander could be a deformed penis, lolling around in filthy sexual juices, or a spermatozoa, or possibly even another, hideously deformed, fetus. At times it looks more like a lump of shit floating around in somebody’s bowels. The salamander mentions that it has grown to three times its previous weight, thriving on the various unmentionable things that it eats. There is another hint at nuclear/chemical warfare in the salamander’s comment on p.3 that “at some point I stopped being myself and became some quite different living creature” – i.e. it has mutated.

But surely the salamander is also a symbol of the artist’s diseased imagination. He takes a perverse pleasure in floating around in all the filth of the sewers, as Tsuge does in exploring the perverted sexuality and necrophilia of modern man. “It’s actually quite enjoyable to get absorbed in this kind of stuff,” the salamander comments on p.6. Perhaps that is the same kind of lugubrious pleasure that Tsuge gets from exploring the darker side of human nature. The salamander is a thoughtful creature, who enjoys carefully studying the various things that float its way. Among its reflections: “I suppose that if your environment and eating patterns change, your constitution can change too.” A conservative critic would read that as referencing the corruption of humanity by the depravity of modern culture. Perhaps the salamander has not so much mutated as adapted.

The salamander’s comments on the fetus are interesting too: is this “strange thing” a representative of humankind? Gondô [8], in conversation with Tsuge, calls this an existential manga and asks if Tsuge had read Sartre and Camus when he wrote it. Tsuge says he had read only Camus, and name-checks The Myth of Sisyphus. Certainly the salamander, with only a vague recollection of where he came from, and no idea how or why he got to where he is now, is a bit of an existentialist. The fact that he has learned to take pleasure in his filthy surroundings also hints at Camus’ accommodation with the cruel and absurd universe: either to commit suicide or to laugh at it. The salamander seems inclined to the latter. But I also seem to detect an echo of Swift. In Gulliver’s Travels Swift has the houyhnhnms puzzling over the strange behavior of men. When Tsuge’s salamander says “I’ve never seen anything as weird as that,” we suspect that like the houyhnhnms who treat Gulliver as representative of mankind, the salamander may indeed be referring obliquely to humankind in general, the weird species that has deposited all this wreckage into the sewers.

Discussion

In the years since these two manga were drawn, the image of the fetus in the sewer has become a staple of horror stories. In the 1970s and ‘80s a slightly younger manga artist, Hino Hideshi (b. 1946), turned the image into a personal trademark with a string of shocking works centering on deformed fetuses and babies emerging from the sewers – some, such as ‘Hell Baby’ (Hino 1995) and ‘Mermaid in a Manhole’ (Hino 1988) would be translated into English and help him acquire a cult international following. In 1990 a low-budget American movie called The Suckling or Sewage Baby, in which an aborted fetus flushed down the toilet in a brothel mutates under the influence of toxic sewage and comes back to kill all the prostitutes, carved out a small niche for itself in underground horror culture. The expression ‘sewer baby’ has entered modern street slang to mean a baby conceived in the sewers from an encounter between semen and menstrual blood flushed down toilets, in the gleeful grand guignol of the 21st century. And yet these two manga could not accurately be described as horror stories. These fetuses do not come out from the sewers to take revenge on humankind – they are entirely passive. If Tatsumi’s story is horrific, it is the horror of social reality, not fantasy [9]. And Tsuge’s story is not so much horrific as disquieting.

The shared motif of the fetus in the sewer is unlikely to be coincidental, and it was Tsuge’s that appeared first. Tatsumi says in an interview with Tomine that he “hardly read any manga” in the 1960s (Tatsumi 2005: 206). Tomine presses him again a year later (Tatsumi 2006: 199) and is told “I am so ignorant… I’m sure there are many talented manga artists, but I don’t know any I could recommend.” This cannot possibly be taken at face value – he and Tsuge were publishing in the same magazine, and there are countless similarities of theme and style. We must generously assume that Tatsumi was pulling Tomine’s leg here. Interviewed a third time by Tomine (Tatsumi 2008: 208), Tatsumi does at least name-check Tsuge and a few other Garo artists, without actually acknowledging influence. Tsuge himself has frequently admitted to borrowing ideas and images from other artists and stated it was common practice in the desperate struggle to make a living from manga in the 1950s and ‘60s. There are several cases of striking parallels between manga drawn by Tatsumi and Tsuge, and as far as I can see, Tsuge mostly seems to have been first.

For Tatsumi, the two symbols of fetus and sewer mark the intersection of some intense obsessions, which are repeatedly reworked in his manga of this period. The fetus-in-sewer motif gets another work-out in ‘My Hitler’ (1969). A man feels frustrated because his girlfriend always washes out her vagina after they have sex, washing his sperm into the sewer. He imagines what would happen if one of them made it to her womb – the result might be a Napoleon, or a Hitler. She leaves him, apparently temporarily, out of fear of a vicious rat that comes up from the sewers to attack her. He feels a strange fellow feeling for the rat and cannot bring himself to kill it. We see the rat sitting in the sewer; a fetus is swept past it on the current (fig. 11 right). The last time he sees his girlfriend, she says “that pest is like a wife to you” and deliberately flirts with another customer at the bar where she works. His parting words to her: “The rat gave birth. Six little ones… cute baby rats… none of them are like Hitler” (201). The message seems to be that humans – or perhaps women in particular – are an inferior life form to rats.. Much later, in 1982-3, Tatsumi would publish Jigoku no Gundan (The Army from Hell), a fantasy epic published in six volumes in which a baby abandoned in a sewer is brought up by rats and ends up being the king of a rat empire that emerges from the sewers to terrorize humankind – a variant on the horror theme of the revenge of the abandoned fetus.

Fig. 11 Tatsumi, ‘My Hitler’ (The Push Man, p. 195)

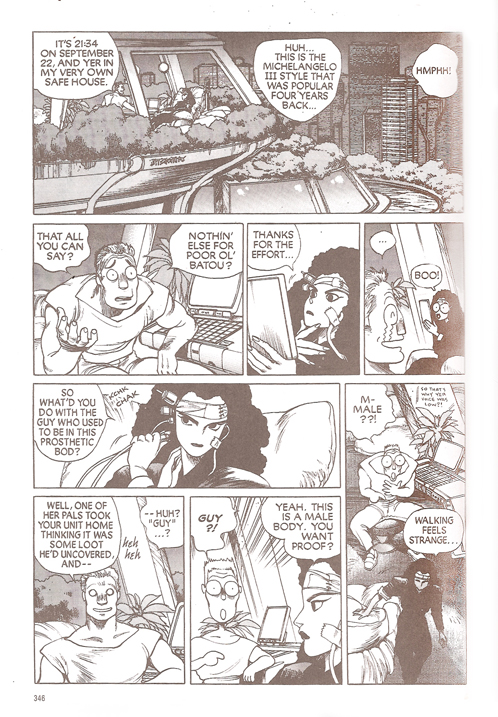

The mute sewer worker returns in Tatsumi’s ‘Eel’ (1970), which arguably recalls Tsuge’s ‘Sanshôuo’ even more closely (fig. 12 left). The man is now part of a three-man team, and they have discovered a pair of large eels swimming around in the sewers. Meanwhile, back home our hero’s girlfriend is pregnant and freezing cold because he cannot afford to buy a stove to heat their shabby apartment. She falls down the stairs, miscarries, and subsequently leaves him to return to work as a bar hostess, calling him a loser. The next day hero catches the two eels and carries them home in a bucket. There is a yakuza waiting at the door to collect his ex-girlfriend’s possessions. Having handed them over, hero chops up one of the eels, grills it and eats it with tears streaming down his face. The story ends with him returning to the sewer with the bucket to free the remaining eel, in a moment slightly reminiscent of the salamander’s swimming off to freedom at the end of the Tsuge story.

Fig. 12 Tatsumi, ‘Eel’ (far left); ‘Black Smoke’ (three frames on right)

A fetus also features in Tatsumi’s ‘Black Smoke’ (1969), which seems to have been designed as another companion piece for ‘Sewer.’ This time our hero’s job involves incinerating garbage. He collects a couple of furoshikis from the local gynaecology clinic and then realizes that one of them contains his own wife’s aborted fetus (fig. 12, right). He knows it is not his because he was rendered impotent and infertile by a traffic accident and his wife has boasted of her own promiscuity. So he deliberately burns down his own house while his wife is asleep, watching the smoke arise from a nearby hilltop. His comment, “it’s a filthy city. Everything here is trash. Eventually someone’s gotta burn it” interestingly anticipates Robert de Niro’s famous line in Taxi Driver (1976), “Someday a real rain will come and wash all this scum off the streets” – albeit using fire rather than water as its cleansing metaphor.

Yet another story from this period, ‘The Burden’ (1969) also dwells upon pregnancy, childbirth and death. The hero strangles his wife to death just as she is on the point of giving birth to their baby. Six months later, as he is finally arrested for murder, he spots a mentally retarded prostitute with whom he had sex earlier in the story, who tried but failed to induce an abortion by standing up to her thighs in a cold river. The baby has been born and she is apparently happy to be petting it (fig. 13 left). An unseen voice finally comments “to survive in the crowd, you have to struggle alone.”

In ‘The Washer’ (1970), a window-cleaner witnesses his own daughter having sex with the president of the firm where she works as a secretary. When next he sees her, he rips off her clothes and forces her to shower – she is defiled. The next time he is out cleaning windows he witnesses his daughter suffer an apparently fatal seizure (eclampsia?) while he looks on helplessly from the other side of a plate-glass window. The story ends with him watching the president seduce another secretary, while on his back he carries the newly-born baby of his own daughter (fig. 13 center). Again a de Niro note is struck when a co-worker comments “You… taught us how the world behind these windows is different. How some stains can’t be washed off.” This hero too is virtually mute, breaking silence only once, to utter the name of his daughter, Ruriko. Like the scream at the disco in ‘The Sewer,’ this one-word utterance signals an emotional breaking-point. These inarticulate heroes are drawn as essentially the same character: a clumsy, broad-faced man with a button nose.

These two stories (‘The Burden’ and ‘The Washer’), both turning on a pregnancy that ends with a living baby, slightly offset the morbid fatalism of the abortion yarns, although both births occur in very grim contexts. Another story, ‘Test Tube’ (1969; fig. 13, right), turns on failure to conceive. A young medical intern serves as a sperm donor for a beautiful woman who has been unable to conceive. After the test tubes filled with his semen fail to produce results, she requests a different donor. The humiliated intern attempts to rape her and ends up in prison.

Fig. 13 Tatsumi, ‘The Burden,’ ‘The Washer,’ ‘Test-tube’

By now the key Tatsumi themes should be apparent. Sexual humiliation, often accompanied by economic inadequacy, so that a woman cannot be satisfied either sexually or materially; lowly occupations that involve cleaning up the mess created by main-stream society (sewer worker / incinerator / window cleaner); and a visceral disgust about the biological processes of sex and reproduction that parallels a disgust about the inhumanity of modern urban mass society – often shading into downright misanthropy, with a corresponding sympathy for animals. We have seen sympathy for rats and eels; other Tatsumi stories go further – one hero lives with his pet monkey (‘Beloved Monkey’ 1970), and another, in abject despair, has sex with a dog (‘Unpaid’ 1970).

Let us turn now to Tsuge. Though there are many stylistic similarities between the two artists, the unremittingly nihilistic atmosphere of the Tatsumi story is more like Tsuge in the years before his mature period. He and Tatsumi both drew plenty of pulp gangster yarns, ghost stories and samurai bloodbaths in the 1950s, but by 1967 Tsuge was only a gekiga artist in the limited sense that he drew characters relatively realistically rather than with the comically exaggerated features associated with mainstream manga for children. In thematic terms, Tsuge was already moving away from grim social realism and into uncharted territory of personal symbolism. He and Tatsumi both make heavy use of animals in their manga, but unlike Tatsumi, Tsuge uses them symbolically rather than literally. No-one has sex with animals in Tsuge cartoons. Instead, the device of making the salamander the narrator of this story is a leap of the imagination of a kind that we do not find in Tatsumi. Tsuge’s nihilism is leavened with a playful sense of humor.

The Tatsumi fetuses are casually discarded by a dehumanized society, and the filth in the sewers runs parallel to respectable society above ground in a fairly straightforward comment on the cynicism of Japanese society in the high-growth years. Unborn babies, like old people in the title story of Abandon the Old in Tokyo, will be discarded if not needed. Tsuge’s fetus is a more ambiguous, teasing image. It reminds one not so much of Tatsumi’s cruelly abandoned abortions as of the fetus floating in space at the end of 2001: A Space Odyssey, which (surely coincidentally) was released in 1969, the same year as Tatsumi’s story and two years after Tsuge’s. We are not quite sure whether it is dead or alive, or what symbolic role it has in this unsettling subterranean world with its playful yet thoughtful salamander.

In many ways this manga is exceptional – I believe it is the only one Tsuge ever wrote with the device of a non-human protagonist, and also the only one using the image of a fetus. Indeed it is striking that among the 22 stories that Tsuge published in Garo (1965-70), there is no direct reference to conception, pregnancy, childbirth, or abortion. There are many on the theme of male/female relations and even a couple touching on marriage, but no offspring are depicted. The only Garo manga to feature a baby is the early work Unmei (Fate, 1965), and even here the baby is found abandoned in bulrushes with 150 gold coins hidden in his clothes – the links between sex, pregnancy and childbirth are bypassed. Interestingly, there does not seem to be a single work by Tsuge in which sex leads to pregnancy and thence to abortion or childbirth. Perhaps when the salamander head-butts the fetus to send it floating away he is symbolizing Tsuge’s reluctance to engage directly with the Facts of Life.

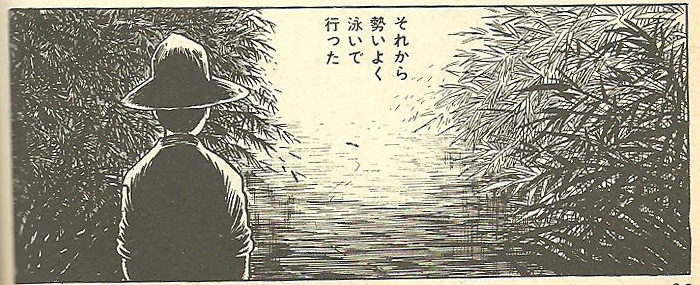

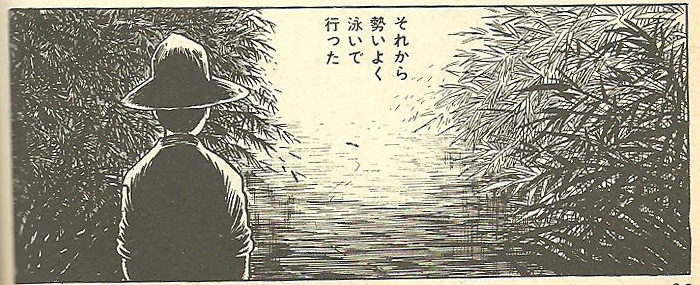

On the other hand, there are plenty of indirect, symbolic references to fertility issues – some obvious, others debatable. The most direct reference is in ‘Akai Hana’ (The Red Flowers, 1967), a rural idyll based on a young girl’s first menstruation, symbolized by red flowers falling into a stream. But Tsuge’s best-known Freudian critic, Shimizu Masashi, sees the hunter’s arrival in some countryside around a swamp in ‘Numa’ (The Swamp) as a phallic incursion into a symbolic womb (Shimizu 2003: 472-473). He also argues that the little pet bird kept by a poverty-stricken cartoonist and his wife in ‘Chiko’ (1966) is a symbolic fetus and the accidental killing of it by the man (fig. 14 far left) is a symbolic forced abortion (ibid. 31-32). The following month Tsuge published ‘Hatsu-takegari’ (The First Mushroom Hunt, 1966), in the final frame of which a small boy, plagued by insomnia over excitement at going mushroom-hunting, finally falls asleep in the womb-like body of a grandfather clock (fig. 14 center left; Shimizu 2003: 432). Shimizu further reads the snow-bound inn inhabited by an elderly man estranged from his family in ‘Honyara-dô no Ben-san’ (Mr. Ben of the Igloo, 1968) as a symbolic womb to which the old man has retreated, noting that Ben sometimes rolls up in an embryonic ball (fig. 14 center right; Shimizu 2003: 164). When the unhealthy young man in ‘Umibe no Jokei’ (A View of the Seaside, 1967) is seen swimming intensely in a swollen sea, Shimizu argues that the young man is embracing his own death, returning to the great womb of them all, the sea (Shimizu 2003: 413) [10] (fig. 14 far right). Note how the white turbulence of the water around him echoes the white aura around the fetus in ‘Sanshôuo’ (fig. 1, far left).

Fig. 14 Tsuge, ‘Chiko,’ ‘Hatsutake-gari,’ ‘Honyara-dô no Ben-san,’ ‘Umibe no Jokei’

These interpretations of Shimizu are open to debate, but I find them largely persuasive. Taken as a whole, Shimizu’s monumental writings on Tsuge amount to arguing that a grand obsession with the Oedipal desire to return to the womb as a form of death wish underlies the entire post-1965 ouevre. ‘Sanshôuo,’ exceptional in so many ways, does share one feature with other works of this period – namely, the watery environment. Whether it be a swamp, a hotspring, a river, a sewer, a gutter or the sea, water is a virtually ever-present feature. For Shimizu (2003 passim), water signifies the womb, the eternal mother, death. I would add that in these Tsuge works water can also signify freedom – perhaps a lonely kind of freedom, the freedom that comes with detachment from society, from responsibility, from human connections of all kinds.

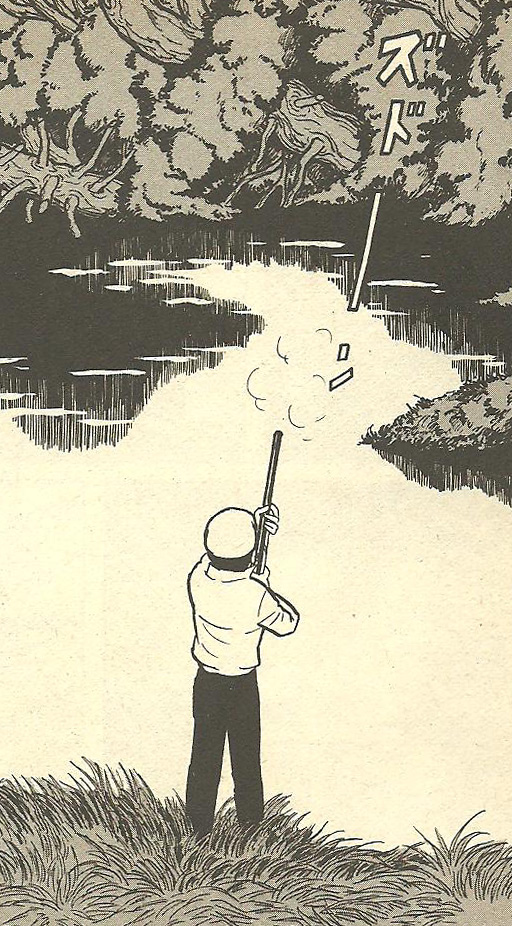

Consider the two images in fig. 15. On the left is the final frame from ‘Numa’ (The Swamp), in which the solitary hunter fires an ambiguous shot into the air above the swamp. On the right is a frame from ‘Sanshôuo,’ in which the salamander splashes cheerfully around in the fetid water of the sewer, saying “that’s right, nobody comes to interrupt me – I am free to do as I please.” The two frames both show an area of white, featureless water, forming a distinct shape. It might not be too much of a stretch to see the outline of a womb with a birth canal leading away from it in these patterns – that is certainly what Shimizu sees. At the same time, the two frames each have a solitary masculine figure: the hunter with the gun as his phallic symbol, and the salamander, in whom the man and his phallic symbol have merged [11]. It is shortly after this scene in ‘Sanshôuo’ that the fetus appears. It is an interruption we would expect to annoy the salamander. On the previous page it has just remarked “other than me there is no-one at all here in this hole. If I think of the whole place as one big house of my own, there’s nothing scary about it all.” Who can say precisely how many layers of irony surround the arrival of the fetus to interrupt this solitary, masturbatory orgy of self-satisfaction? It is almost as if the salamander were himself a fetus, resenting the arrival of a twin.

Fig. 15 ‘Numa’ (left), ‘Sanshôuo’ (right)

Later the same year (1967), Tsuge published ‘Nishibeta-mura Jiken’ (The Incident at Nishibeta Village) [12]. A travelling fisherman encounters a young man who has escaped from a lunatic asylum. The escapee (who seems perfectly sane) accidentally traps his foot in a hole in the rock with a small fish stuck underneath it. The supposedly mad young man is taken back to captivity, whereas the fish, which has also endured a horrible experience, is returned to the river by our hero. After pausing in the shade of the pussy willow, it swims off into the distance, apparently unharmed by its experience (fig. 16). As it does so, it bears a striking resemblance to the contented salamander in the earlier story. Both creatures are bathed in an ethereal light. A mutant salamander in a stinking sewer; a freshwater fish in a mountain stream. Ultimately both will serve as multilayered symbols of masculinity, escapism, freedom. And if there is something comic about the symbols chosen to represent these things, it can be put down to a layer of ironic self-awareness that is part of the unique charm of Tsuge Yoshiharu.

Fig. 16 ‘Nishibeta-mura Jiken,’ final frame

REFERENCES

Hino, Hideshi (director). 1988. The Guinea Pig: Mermaid in a Manhole. Citrus Springs, Florida: Unearthed Films (animation).

Hino, Hideshi. 1995. Hell Baby. New York: Blast Books.

Norgren, Tina. 2001. Abortion Before Birth Control: The Politics of Reproduction in Postwar Japan. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Shimizu, Masashi. 2003. Tsuge Yoshiharu o Yome (Read Tsuge Yoshiharu!). Tokyo: Chôreisha.

Tatsumi, Yoshihiro. 2005. The Push Man and other stories. Montreal: Drawn & Quarterly.

Tatsumi, Yoshihiro. 2006. Abandon the Old in Tokyo. Montreal: Drawn & Quarterly.

Tatsumi, Yoshihiro. 2008. Good-bye. Montreal: Drawn & Quarterly.

Tatsumi, Yoshihiro. 2009. A Drifting Life. Montreal: Drawn & Quarterly.

Tatsumi, Yoshihiro. 2010. Black Blizzard. Montreal: Drawn & Quarterly.

Tsuge, Yoshiharu. 1985. ‘Red Flowers’ (translation of ‘Akai hana,’ 1967). In Raw vol. 1 #7. New York: Raw Books.

Tsuge, Yoshiharu. 1990. ‘Oba’s Electroplate Factory’ (translation of ‘Oba Denki Mekki Kôgyôsho,’ 1973), in Raw vol. 2 #2. New York: Penguin Books.

Tsuge, Yoshiharu. 1994a. Akai Hana (Red Flowers). Tokyo: Shôgakkan.

Tsuge, Yoshiharu. 1994b. Neji-shiki (Screw-style). Tokyo: Shôgakkan.

Tsuge, Yoshiharu. 2003. ‘Screw-Style’ (translation of ‘Neji-shiki,’ 1968). In The Comics Journal #250. Seattle: Fantagraphics.

Tsuge, Yoshiharu and Gondô, Shin. 1993. Tsuge Yoshiharu Manga-jutsu (The Manga Art of Tsuge Yoshiharu). Tokyo: Wise Shuppan.

Tsurumi, Shunsuke. 1991. Manga no Dokusha toshite (As a Reader of Manga). Tokyo: Chikuma Shobô.

NOTES

[1] In 1950 Japan’s population stood at 83.6 million. By 1970 it had reached 104.3 million.

As for urbanization, definitions vary, but according to the Population Division of the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Japan’s urban population climbed from 34.9% in 1950 to 53.2% in 1970, a rise of 18% in 20 years. [back]

[2] Historical Abortion Statistics Japan [back]

[3] The word makes its first appearance on the cover page of Tatsumi’s 1957 work, Yûrei Takushi (Ghost Taxi). [back]

[4] To date Drawn & Quarterly have published five volumes of Tatsumi’s manga (Tatsumi 2005, 2006, 2008, 2009, 2010). [back]

[5] The only works of Tsuge that have been translated into English are three short stories, ‘Red Flowers,’ ‘Mr. Oba’s Electro-plating Factory’ and ‘Screw-style.’ See bibliography for details. There are also very poorly translated scanlations of ‘Numa’ (Marsh) and ‘Chiko’ (Chico) floating around the internet. His works are readily available in Japanese, and all the ones discussed here are included in Tsuge 1994a or Tsuge 1994b, each of which is a handy paperback currently available at Amazon Japan for 610 yen, or about $7. [back]

[6] Tsuge admits in conversation with Gondô (Tsuge and Gondô 1993 vol.2: 57) to being influenced by Ibuse Masaji’s short story, also called Salamander (Sanshôuo), in which an overgrown salamander gets stuck while struggling to get through the narrow opening of its underwater cave and reflects amusingly on its predicament. Tsuge says he does not particularly like the Ibuse tale but happened to have read it recently. [back]

[7] The giant eye anticipates his most famous work, Screw-style (‘Neji-shiki’), in which a boy urgently needing a doctor to heal a jellyfish sting on his arm finds himself in a town full of opticians; clocks appear in many works, including the work published immediately before this one, The First Mushroom Hunt (‘Hatsutake-gari’) (see fig. 14 center left); the bird house anticipates The House of Mr. Lee, (‘Li Ikka no Ie’), in which the eponymous Mr. Lee can converse with birds; the dead dog resembles Goro in The Dog at the Pass (‘Tôge no Inu’), etc. [back]

[8] Gondô Shin, a close friend of Tsuge’s, played Boswell to his Johnson, producing a hefty two-volume record of conversations (Tsuge and Gondô 1993) in which the two men discuss every single comic Tsuge ever published. [back]

[9] Googling for terms like ‘fetus/foetus/embryo’ and ‘sewer’ will produce quite a few media reports of actual cases like this, most of them from the United States. [back]

[10] Tsuge would return to the symbolic sea many times, notably in ‘Yanagiya Shujin’ (Master of the Yanagiya, 1970) and ‘Umi e’ (To the Sea, 1987). The famous critic and manga fan Tsurumi Shunsuke entitles his essay on Tsuge (1991) simply ‘Umi’ (Sea). [back]

[11] Tsuge’s salamander is male, since it refers to itself as ore, a specifically masculine form of the first person pronoun in Japanese. [back]

[12] See my paper forthcoming in the International Journal of Comic Art (spring 2011): “The Incident at Nishibeta Village: A Classic Manga by Yoshiharu Tsuge from the Garo Years.” [back]

BIO

Tom Gill was born in Portsmouth, UK and got his doctorate in social anthropology from the London School of Economics. Since 2003 he has been a professor at the Faculty of International Studies of Meiji Gakuin University, Yokohama, Japan. His research interests include marginal labor, homelessness and masculinity. He has written many papers in English and Japanese on these topics and one book – Men of Uncertainty: the Social Organization of Day Laborers in Contemporary Japan (State University of New York Press, 2001). His favourite mangaka is Tsuge Yoshiharu, and his favourite American cartoonist is Chris Ware. “Actually I would not call comics a side interest,” he says. “Tsuge Yoshiharu is the voice of homeless, marginalized masculinity in Japan and Chris Ware is his American blood brother.”

Editor’s Note: For other Hooded Utilitarian articles on Tatsumi Yoshihiro and Tsuge Yoshiharu, please click on the name tags below.