Originally presented: Panel on Frames and Ways of Seeing in Modernist Narrative at The Tenth Annual Modernist Studies Association (MSA) Conference, Nashville, TN, November 2008.

Author’s introduction (“disclaimer”)

This paper was presented at the Modernist Studies Association conference two years ago. As such, the audience for the talk was not comics scholars, or, even, necessarily people who were interesed in comics. The paper is pitched to that audience and therefore says quite a number of things about comics that are fairly obvious to the comics scholar (or even just the perceptive comics reader). In fact, it even says things I know to be debatable, and even incorrect, since those things weren’t my primary concern. So, yes, I know that “The Yellow Kid” isn’t the first comic strip in U.S. newspapers (to say nothing of the world at large), but since splitting those hairs wasn’t the point of the paper, I used that as a generally “known” reference point.

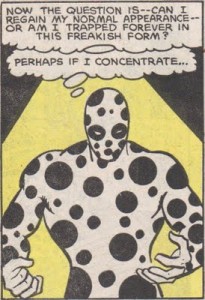

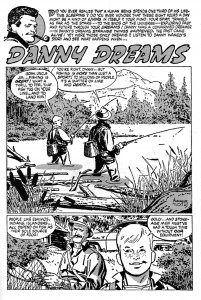

I was invited to participate in a panel on “frames and ways of seeing in modernist narrative” after one of the participants in the original panel dropped out. As I recall, all three of the original panelists were from the University of Toronto, studying under/with noted modernist scholar, Melba Cuddy-Keane. Cuddy-Keane got in touch with my dissertation advisor at University of Maryland, Brian Richardson, and asked if he knew anyone interested in frame narration and modernism. Brian got in touch with me, recalling a paper I had written for him many years previous as a graduate student. That paper, however, was already forthcoming in Narrative, and I wasn’t really interested in recycling the material. So, I took the opportunity to apply some of the research I was doing on time, modernism, and comics and to write some of that out, rather than merely having it bounce around in my head. All of this is the long way of saying that the paper was even more rushed and “tossed off” than the typical conference paper, since I was a late addition to the program. At this point, I feel as if there may be nothing particularly revelatory here, as much of this material feels (to me, anyway) as if it’s fairly obvious and straightforward and covered elsewhere in the literature. Since this is a blog (my brother’s no less), I don’t feel quite so guilty about letting it see the light of day, as long as nobody really feels like it reflects the care I generally take in my scholarship. Things that make me cringe a bit, are… a) sources cited, but no bibliography listed. The sources are mentioned, for the most part, in the paper itself, but obviously, a bibliography should be included. Since I was only reading it out loud at the time, however, and I knew the sources, I never typed them up. (At this point, this note may be taking longer than it would take to type the sources… but let’s not ruin a fairly boring and mediocre story). 2) The paper also includes various notes to myself telling me to elaborate on this point or that orally. Obviously, for written publication, I should turn those into more coherent written claims… but I’m just writing a disclaimer instead. [Many of these were references to the images, so I’ve replaced them with “See Fig. X” reference. -ed.] 3) The quality of the scans is sometimes pretty bad, as well. My scanner is just an 8 x 11 and some of my sources were much bigger. I should have gone to the Artist Formerly Known as Kinko’s and done the scans on a larger printer to get things right… but, again, I reveal the generally slipshod nature of my efforts on this particular piece. All of this is why I told Noah and Derik that they could have this conference paper if they wanted it… but that I was generally unsure of its “ready for prime time” (using the term loosely) status. Derik and Noah decided to run it anyway (making me think that they reall need more submissions for this feature [We do! Send us something -ed.]), so, here it is “warts and all.”

“Through Space, Through Time:” Four Dimensional Perspective and the Comics by Eric Berlatsky

Whether pamphlet-form comic books, cramped newspaper comic strips, or more traditionally codex-form “graphic novels,” comics have only recently started to receive serious critical attention as “art objects,” as opposed to mass culture ephemera. The biggest breakthrough in comics criticism is still undoubtedly Scott McCloud’s 1993 book Understanding Comics, a book that makes a bold play for considering comics as “art,” by bypassing the typical starting date for its history. The standard date, particularly in America, is, of course, 1895, marking the beginning of R. F. Outcault’s Hogan’s Alley as a newspaper comics page in The New York World. This date, would, of course, place the origins of the newspaper comic strip in close chronological proximity to the “high art” development of modernism. However, McCloud’s choice to define comics as “sequential art,” or, in the longer version, “juxtaposed pictorial and other images in deliberate sequence,” allows him to include pre-Columbian picture manuscripts, the Bayeux tapestry, Egyptian painting, Trajan’s column, and Hogarth’s “Harlot’s Progress” as comics, along with other, more likely, suspects, like Rodolphe Topfer’s “picture stories” of the mid-nineteenth century (McCloud 10-17). McCloud discards some of the elements of earlier definitions of comics in order to detach the era of comics’ increasing popularity (the twentieth century) from its definition, suggesting that some of the greatest achievements of older “high art” are, in fact, comics. While this has the potential to raise the culture caché of comics as a medium, it also obscures the ways in which the form reflects and takes part in the modernist project and the advent of modernity.

Continue reading →