By James Romberger

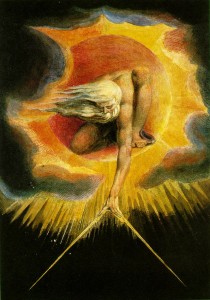

Thought forms in the mind as a combination of word and image. For that reason, cartooning is a direct, intimate means to communicate subjective thought to a reader. This is why many of the greatest comics are by artists who write their own narratives. Still, it is rare that a single person can both draw and write well, much less produce a work of blinding genius; one can spend a lifetime mastering either discipline. However, a writer’s words can be brought to life by an artist of the prerequisite abilities, one who can accomplish what in a film might require an unlimited budget and even pass beyond, to the unfilmable. The comics form offers infinite possibilities to writers and artists who are willing to work together. But the focus on autonomy in alternative comics has left collaboration largely in the hands of comics’ mainstream, where it has been greatly influenced by the economics and labor/management relationships of periodical publishing. The reader’s indulgence is asked for a short history of those relationships, as a prelude to an explanation of the artist’s contribution to the collaborative process in comics.

Bullpen variations

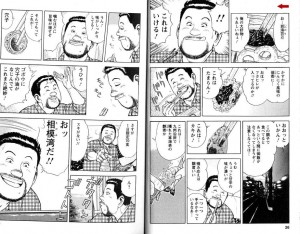

“Bullpen” comic book production was initiated in 1936 by groundbreaking cartoonist Will Eisner and his partner Jerry Iger to meet the rising demand for content in the new medium of the comic book. Studio staff was divided into an assembly line of piece-workers: writer, penciller (which might subdivide to layout, character and/or background artist), inker, letterer, and colorist. The bullpen became standard for comics because it was expedient to publish books on time and made it so no one creative person was wholly responsible for, or entirely invested in, what was claimed by publishers as properties done by “work-for-hire” employees. Comics history is crowded with “ghost” creators like Carl Barks and Bill Finger, who worked in near or actual anonymity and were not compensated fairly for their contributions. For many years, that was the accepted status quo.

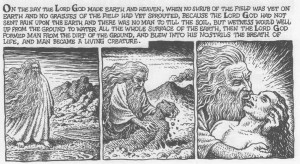

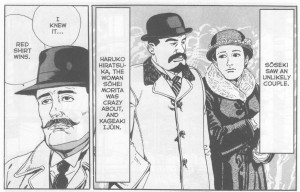

In the early 1950s at E.C. an odd exception to the standard sweatshop mold led to some of the best comics published to date. Editor Harvey Kurtzman recognized that in comics, the crux of storytelling is in the layout or breakdown that integrates text with image, the pencil drawings that establish the structure and style of the design. The layout finds the flow of viewpoint and character interaction. Kurtzman made articulately composed page diagrams for all of his stories with every basic element drawn roughly in place, which his artists then rendered to finish. Still, individual stylists like Wallace Wood and John Severin did some of their finest work for Kurtzman’s war comics “Two-Fisted Tales” and “Frontline Combat.” Kurtzman demanded a high degree of accurate detail for period stories; his artists respected his guiding intent and invested their drawings with research, observational realism and great passion. Kurtzman also grasped the importance of color and worked side-by-side with colorist Marie Severin to enhance his narratives immeasurably. In these atypical collaborations, Kurtzman was the writer and also the primary storytelling artist. His finishing artists acted more as elaborators, but it was they who signed the stories, Kurtzman only took credit as editor.

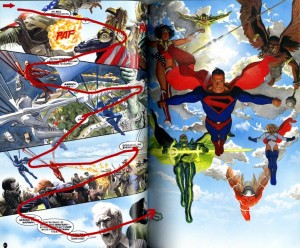

Another version of the Bullpen was introduced with what became known as the “Marvel method” in the 1960s. Editor Stan Lee enlisted artists such as Jack Kirby, Steve Ditko and Gene Colan to draw their stories from brief plots outlined by Lee in a short note or phone call, or to invent the stories from whole cloth themselves and make notes that described the narrative and suggested dialogue in the page margins. After the fact, Lee added captions and balloons based on those notes, in his words a job often “like filling in a crossword puzzle.” Lee was able to do this because on their own, these experienced storytelling artists could initiate and motivate characters, construct their environments and produce complete comic book page sets. For what often amounted to copy-writing, Lee claimed full writer credit and pay. In this arrangement, the pencillers were also uncredited plotters and co-writers.

Jack Kirby writes continuity, which Stan Lee ignores, from the original art for Fantastic Four Annual #3, 1963

In particular, Kirby was the single greatest driving force in the foundation of Marvel’s popular multimedia empire; his creative input on “The Fantastic Four” alone encompassed a multitude of imaginative characters and settings. To be fair, Lee helped make the books successful with his unifying voice; in the letters pages and in his “Bullpen Bulletins” he created an illusion of family that resonated with young readers. He did plot and write some of the stories and he credited his artists (for their art) prominently. But Lee also failed to defend his collaborators’ interests to management. According to Kirby biographer Mark Evanier, promises were made to Kirby about royalties that were not kept and Kirby found no one to address his concerns to but Lee, who said, “I have nothing to do with that.” Kirby subsequently left the company rather than be further exploited. Kirby’s children still struggle to gain any portion of the multibillions Marvel makes from the comics, films and merchandising derived from their father’s work.

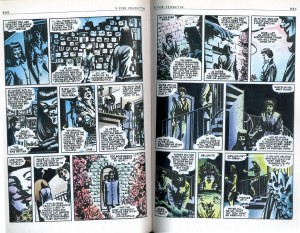

Too many battles were fought by the artists and writers of comics for their rights to be detailed here, but in the early 1980s, major publishers instituted “creator-owned” contracts for special projects in which artists and writers share copyright as co-authors, on an equal footing. Mainstream comics are still closely overseen by an editor, who selects teams and then acts as intermediary to writer and artist, even in creator-owned projects. The editor can facilitate their best efforts and contribute greatly to the storytelling by honing the creator’s individual contributions, depending on the sensitivity and sensibility of their recommendations or dictates. Some other holdovers from the bullpen days are still present in mutated form. While some artists finish their own pencil drawings in ink, others still have their pencils inked or finished by other artist. Inexplicably, though color makes a profound impact on the reader, the colorist still holds the lowest-paid job in comics. Perhaps as a consequence, few artists in comics do their own color, which is now most often applied by digital artists, with mixed results. Also, while alternative cartoonists often prefer to letter in their hand, mainstream artists do not and digital fonts have supplanted hand lettering almost entirely, not least because digital balloons and captions are editable until the last moments before publication. Whatever the rationale for their use, digital typesetting loses the qualities of illumination that are an important advantage of the comics form. Inkers, colorists and letterers of varying degrees of skill and artistry can greatly enhance, or ruin a book. But, it should be reiterated that the penciller controls the layout and storytelling and so is the primary artist.

Make It So

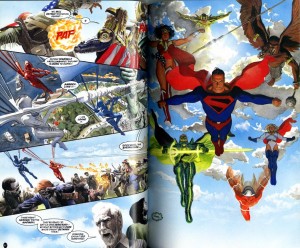

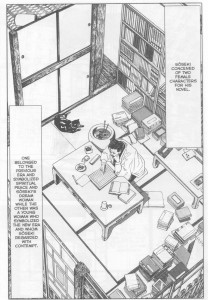

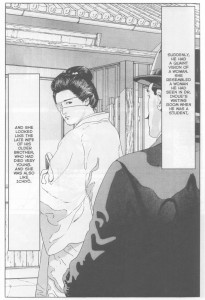

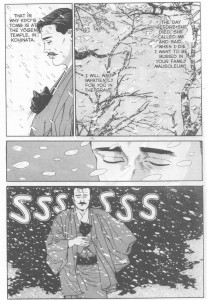

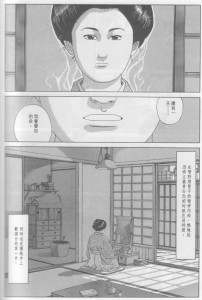

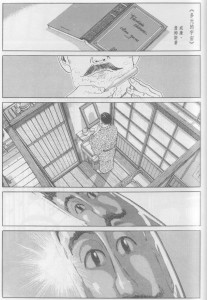

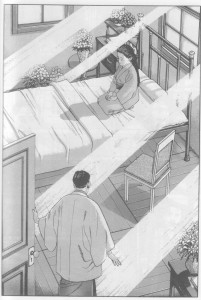

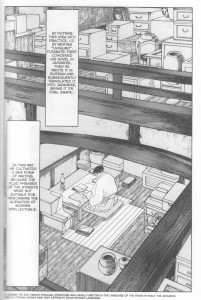

Currently in mainstream comics, an editor works with a writer to provide an artist with a document that resembles a movie script. This text describes the settings, the personalities, speech and actions of the depicted characters, as well as the trajectory and intent of the scenes. However complete this may sound, it’s not; the artist’s job is daunting. In a film, the lion’s share of the credit does not usually go to the writer, but to the director, the person in charge of the product of a largely visual medium. In comics, the artist must engage complex skills that approximate everything that would be involved in making a movie: direction, cinematography, casting, actors, production design, set design, lighting, costume, makeup, special effects and every other function, including that of the person who tapes around the actor’s feet to mark where they were standing.

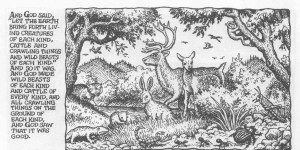

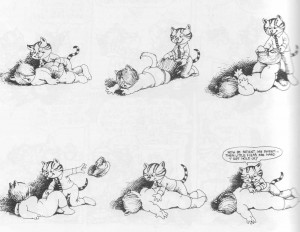

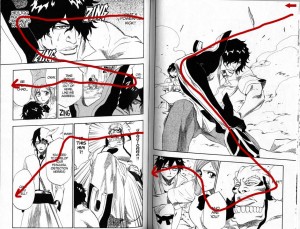

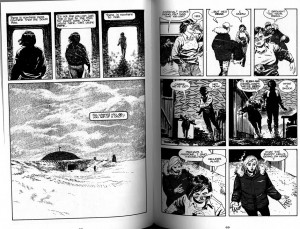

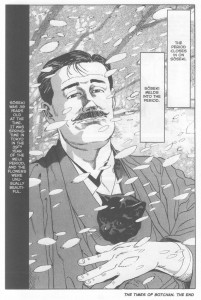

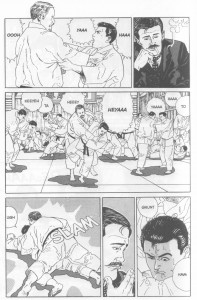

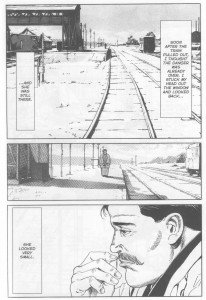

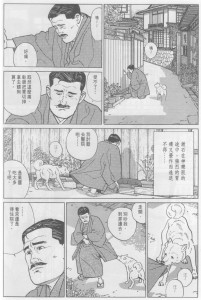

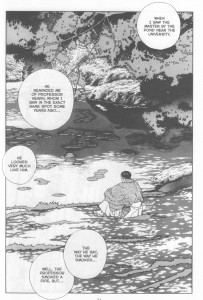

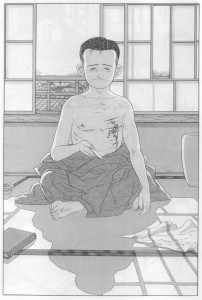

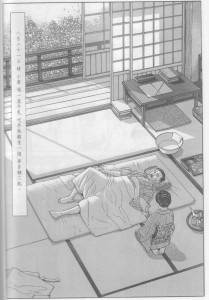

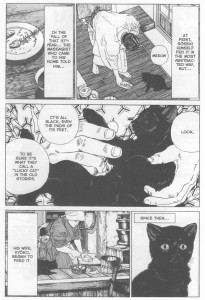

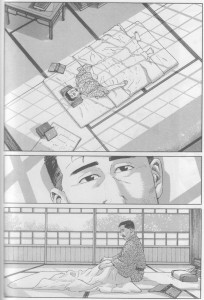

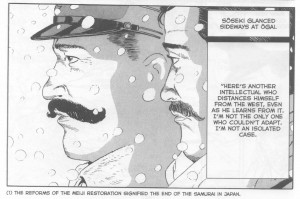

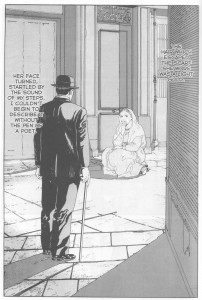

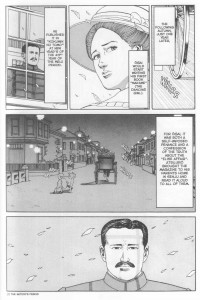

One challenge for the cartoonist is that one’s “actors” must play their parts with well-timed reactions and believable emotions, expressions and gestures. That is no small feat of itself. The characters must reflect the diverse variability of human form. They must also be recognizable (“on-model”) from all angles or lines of sight, as must the settings, objects, vehicles and fashions, which also must all be true as possible to the time and place depicted, down to the smallest necessary detail. All of the depicted persons, environs and objects must also be executed in perspective and reflect the influences of light and the natural elements. In other words, the artist must understand and render everything that in a film is recorded by a cameraman. Like animators, cartoonists visualize movement within three-dimensional space as they simulate the viewpoint of a weightless steadicam; they engage a complex form of draftsmanship that can be described as “motion perspective.”

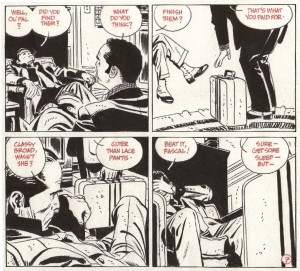

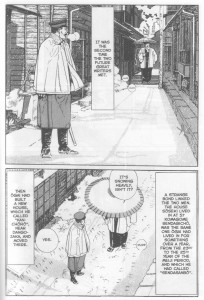

Alex Toth, motion perspective from the original art for “Torpedo.”

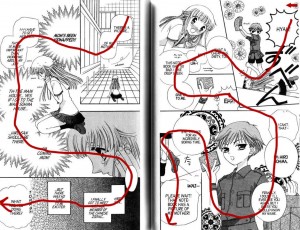

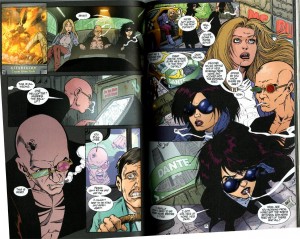

Quintessential moments must be chosen to freeze in panels. A further complication is that the characters must be composed in each panel in their order of speaking, as indicated by the script. The refined composition of each panel acknowledges not only the design of the images viewed simultaneously in direct proximity on the page and on the facing page (a two-page “spread”), but also those throughout the entire narrative. The illusion of movement occurs in the spaces between panels, where positive and negative space flip, creating visual rhythms that sync with the beats of the broken-down blocks of words, as the reader’s eye is led where the artist wants it to go. At the layout stage, artists might expand upon, or deviate significantly from a script in order to make a story work effectively. For instance, the addition of panels can serve to compress time or make actions clearer, captions can be bumped to panels behind or forward in order to gain room for a larger drawing, captions can be added or deleted to clarify character. In truth, it would be difficult if not impossible to find a cartoonist who did not add many acting characters, objects, architecture, flora and fauna of their own device throughout the execution of a given story, all of which contribute substance to the narrative.

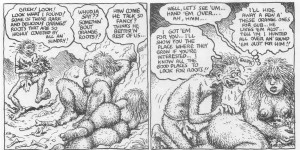

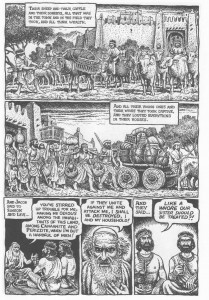

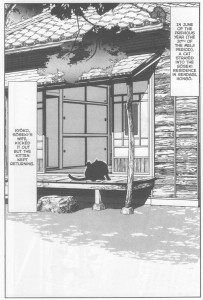

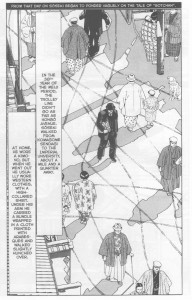

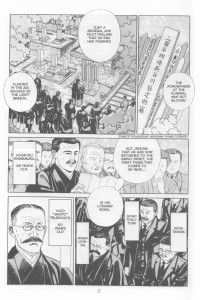

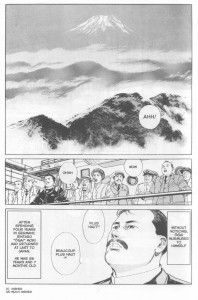

Artist Tony Salmons notes three seemingly innocent words often seen in scripts, “a crowd gathers.” Salmons says, “A writer scripts or merely plots this line down on paper and goes on to the next scene. I spend an entire day researching, casting, lighting and acting out that crowd. Is it an opium den? SF or Hong Kong? Texas? German beer garden? Rainbow room at 30 Rock? What kind of crowd? If I do it with total commitment the considerations can go way beyond this. And the writer’s contribution is 3 words, ‘A crowd gathers.'” No matter what the story requires, the artist must make it so.

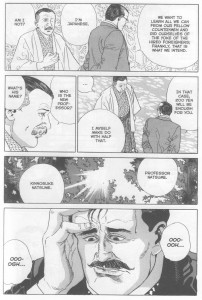

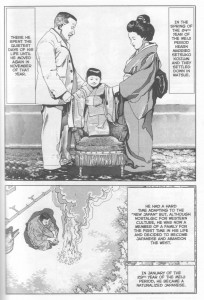

Tony Salmons, detail from the original art for “The Strange Adventures of H.P. Lovecraft.”

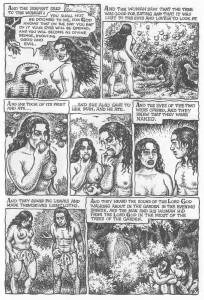

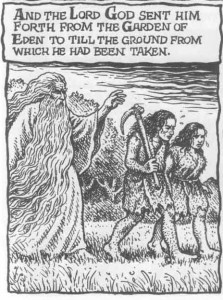

Additionally, ideas occur in the process of drawing. The artist may see a better way to articulate a scene after it has been laid out, when the story has achieved sufficient form that new visual potentials emerge. Artist P. Craig Russell has detailed one of the artist’s many unique contributions to comics storytelling, a technique he aptly calls “parallel narrative,” sequences invented by the artist that diverge from the script to depict scenes that are not in the text, that are intended by the artist to counterpoint the text. In comics, the onus is on the artist to make the story work. For that, the artist must find ways to “believe” what they are drawing, to feel the motivations of the players, the touch of a lover, the heat of battle or the cold night wind of the desert and express them to the reader.

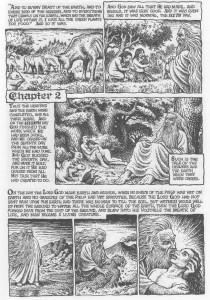

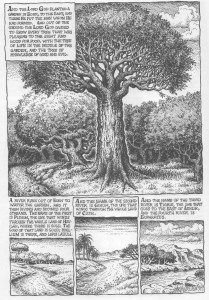

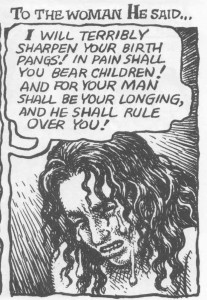

Comics demand an immersion on the part of the artist that goes far beyond the job description of an illustrator. Illustrations are derivative entities that are subordinate to text, isolated visualizations which can operate either as redundant to the words or as commentary on the words, ranging from literal to oblique. In comics, the text is most often visually subordinate. The images are imbedded with far more information than the words. The words represent sounds and qualify the images. The text need not say something that is clearly shown in the pictures. Illustrations can enhance or challenge the reader’s visualization of prose, but comics are a full-blown realization of narrative, with the intimate interactivity of a book and with more potential for expansive spectacle than film.

For most of comics’ short history, the writing was often the weakest element and so highly skilled interpretive cartoonists have longed to work with better scripts. As the graphic novel gains ground in the book trade, more serious writers will want to explore the form. This could result in more sophisticated and revelatory collaborative efforts. It should be made clear that comic artists are usually paid more per page than writers, but for as long as credits have been given, artists have willingly shared them equally with writers. But now, the equilibrium of credit has slipped askew. Increasingly one sees collaborative books credited and publicized with the emphasis on the writer alone. Such selective crediting causes further chain reactions. In the catalog listings of libraries and booksellers, the “Author” is listed first. In the case of graphic novels, it is assumed that the name credited as “writer” is the “author,” unless specified otherwise. The artist might not even be included in bibliographic data unless credited by the publisher as a “co-author.” Amazon’s default system for graphic novels lists writers as “author” while artists are diminished to “illustrator”, a subordinate creator and in no way a “co-author.”

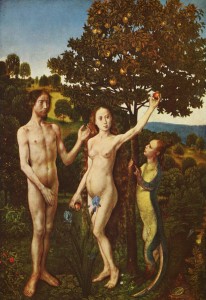

This diminution of the artist’s perceived role in comics has repercussions for alternative and mainstream artists alike. Artist Jillian Tamaki spoke of her process collaborating on the graphic novel “Skim” with her cousin, the writer Mariko Tamaki: “(Mariko) was not precious about it. It was basically just a play and there was no description of what they were doing when they said something, or where they were…it was me putting the pacing in, and the rhythms and the timing and the backgrounds….it took about two years.” But when “Skim” was nominated for a Canadian book award, the writer was the only one cited for the honor. Writer Alan Moore makes sure that his artists share equal credit, but Neil Gaiman’s name dominates the cover of the exquisite book P. Craig Russell made of “Coraline.” It can and has been claimed that it is Gaiman’s name that sells books, but a case can also be made that Russell’s mastery of the comics medium is such that his adaptations of Gaiman’s prose stories are more resonant in their form than the comic books that the writer has scripted. Even as the medium is poised to evolve into a sophisticated art form, critics often closely analyze what they perceive as “the writing” of a given book, but ignore or barely describe the art, perhaps because they are unaware of the interrelativity of text and art in comics, or perhaps because the publisher’s packaging and promotion tells them that the writer is the primary creator.

This trend will discourage thoughtful non-writing or interpretive artists from involvement with the medium. Because of the labor-intensive nature of comic art, a graphic novel can take an artist years, even decades to complete. In the current climate, collaborative comics become much less worthwhile for the artist. The remedy to this situation falls to the individuals who work in comics. Artists should avoid the “illustrator” label and stipulate a co-authorship credit for themselves in their contracts. They might find that there already is a co-authorship stipulation in their contracts, which has not been honored by the publisher’s packaging and publicity arms, or that there is some ambiguity in the distinction between “co-creator” and “co-author,” or they could discover that there is a contractual clause which calls for “credit according to current practice.” This means that the more artists allow themselves to get less credit, the more it becomes current practice. Also, writers could heed Alan Moore’s positive example and not allow their credit to override that of their partners. Both creators should ensure that their publishers direct their design and promotional departments to incorporate the contractually stipulated credits and see that book trade entities correctly list them. The alternative is that artists accept a diminished role and lose their hard-won rights.

In the end, the credit issue is about more than just the bruised egos of artists and writers. Debates about the validity of authorship itself are set aside when the realities of book publishing and movie deals come into play. A great comic need not ever be made into a movie if it resonates sufficiently within the parameters of its form, but when films are made and when book royalties accrue, artists and writers should share in the credit and proceeds as co-authors. For the artist, comics are a difficult form and the work involved in a graphic novel is not undertaken lightly. If his or her contributions to the whole experience of reading are seen as expendable tools of the writer, the evolution of comics is at risk.

Sources

Jack Kirby scan courtesy of the Howell-Kalish collection. From the Jack Kirby Museum’s Original Art Digital Archive.

Evanier, Mark. Kirby: King of Comics. New York: Abrams, 2008. p. 157.

Green, Karen. Words and Music…er, Images. Comic Adventures in Academia, column on Comixology website, 4/3/2009:

http://www.comixology.com/articles/212/Words-and-Music-er-Images

Lee, Stan with George Mair. Excelsior! The Amazing Life of Stan Lee. 2002. New York: Fireside/Simon and Schuster, p.146.

Russell, P. Craig. Parallel Narrative. Video series posted online: www.pcraigrussell.net

or http://vodpod.com/watch/1296908-pcr-tv-parallel-narrative-murder-mysteries-part-1

Salmons, Tony. Quote from private correspondence. August, 2010.

Tamaki, Jillian. Quote from transcript of panel discussion: Inside Out: Self and Society in Comic Art. Moderator: Calvin Reid. St. Mark’s Church, Howl! Festival, 9/10/2008:

http://www.comicsculture.net/