Picking on superhero comics for being dumb is like punching a baby for not walking well, but there’s something about the inexplicably popular work of Geoff Johns that invites derision. It might be that his influence has grown by leaps and bounds over the past decade, culminating in his current position as the Chief Creative Officer at DC Comics, with his style of writing now being the shoddy model for the entire company to follow. This style has its proponents, even among people who should really know better, due to its constant hammering on nostalgia buttons, emphasis on “awesome” moments, and constantly-expanding stakes that reassure readers a long-term plan is in place, no matter how idiotic it is. What’s more, regular injections of gruesome violence and attempts at making everyone a badass make Johns’ comics perfect for those developmentally-stunted members of the audience who want to pretend that the kiddie entertainment of their childhood is all grown up now that it’s full of rape and dismemberment. But look at it with any sort of critical eye, and while occasional moments of dumb action-movie enjoyment might surface, they are buried in an overwhelming self-seriousness that makes the whole enterprise laughable.

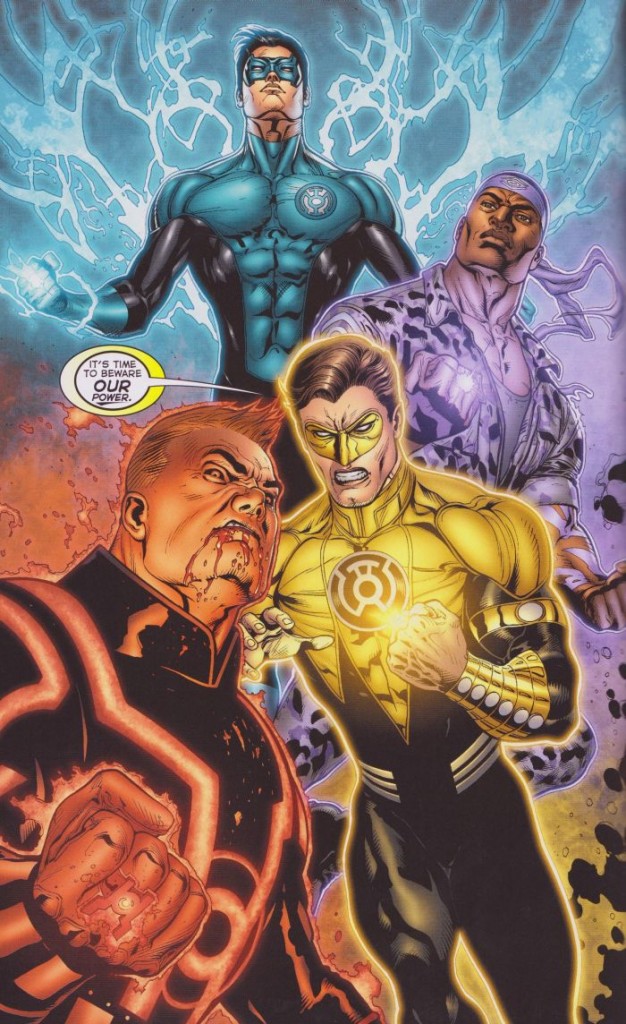

So, here’s a look at Johns’ signature franchise, Green Lantern, which he revived in the mid-00s through a convoluted resurrection and redemption of a hero who had been turned into a maniacal mass murderer, then turned into the driving force behind much of DC’s line-wide plotlines, culminating in the “Blackest Night” crossover, the ne plus ultra of Johnsian large-scale death and destruction, a clusterfuck of obnoxious zombies, resurrected characters transformed into badasses, and ridiculous plot points treated with the utmost seriousness. But that comes later; let’s start at the beginning, shall we?

Part 1: Back to Basics, But So Much Cooler This Time, Dudes

Johns got to make a clean start with Green Lantern with a new series that started in 2005, having just brought Hal Jordan, the most popular version of the character ever since sometime in the 60s, back to life through a complicated retcon (an abbreviation for the comics fan term “retroactive continuity”, in which writers “fix” previously-written stories by telling what “really” happened) that absolved him of the crimes committed when, in an attempt to shake things up, a 90s storyline had him go crazy, kill off all of the fellow members of his army of space cops, try to destroy the universe, and eventually die saving the Earth. But now he’s back, and it turns out he was actually possessed by some sort of fear entity, and…wow, just trying to explain the basic backstory of this comic is numbness-inducing. It’s bad enough that Johns regularly takes a few pages at the beginning of issues to get readers caught up in the ongoing plot. When even superhero comics readers need regular reminders and recaps to be able to keep up with your stories, you might have tangled them up a bit more than is necessary.

So anyway, as the series begins, Hal Jordan is back to being an Earth-bound superhero, and since one of the core aspects of his characters back in the day was that he flew planes, Johns has him join the Air Force as a fighter pilot. Of course, the Air Force is a branch of the military, but Hal is too cool to have to go through any of the rigamarole of recruitment or orders; no, he simply asks a buddy to have a general let him join up and become a pilot, and even though he was kicked out years ago for punching that same general (another bit of fantasy; strike an officer, you just get a ticket home without any other consequences), they let him back in because, hey, he’s Hal Jordan and he’s awesome.

Why Hal needs to fly planes to get his adrenaline kicks should be the main question here, since he has a ring that lets him create anything imaginable and zoom around the universe at presumably faster-than-light speeds (since he’s always traveling to other star systems) anyway, but it’s mostly the nostalgia factor at work; that’s what he did back in the 60s (when planes were futuristic and glamorous), so that’s what he does now, dammit. Johns also seems to be attempting to ground the character and give him real-world concerns, which mostly serves to make things pretty boring whenever Hal isn’t wearing green. Johns must have realized this, since he ended up pretty much completely dropping any attempts at non-Green Lanterning and focusing solely on space-bound action and intrigue.

Many of the early issues are spent establishing the oh-so-tiresome theme of “overcoming fear”, with characters constantly going on about how everyone is fearful, especially those who don’t want to repopulate Hal’s rebuilt hometown of Coast City (the destruction of which, along with the deaths of its populace, being what drove him into villainy), as if it is more susceptible to chaos than anywhere else in the DC universe. But Hal is the man when it comes to combating fear, as he and his fellow Green Lantern John Stewart exposit to the reader when they explain how they’ve overcome their rings’ former weakness against the color yellow (yes, really): “Feel fear. Overcome it. Not a problem.” Yes, this is serious, insightful treatment of battles between colors.

The rest of the time is spent revitalizing old villains in “edgy” new ways. There’s the Shark, a super-evolved, uh, shark that has arms and legs and communicates telepathically in sentence fragments that all have to do with eating brains. He’s a near-mindless beast, but he also wears what appears to be a wetsuit for some reason, and Johns makes him mean and nasty by giving him a scene out of Jaws by way of Herschell Gordon Lewis:

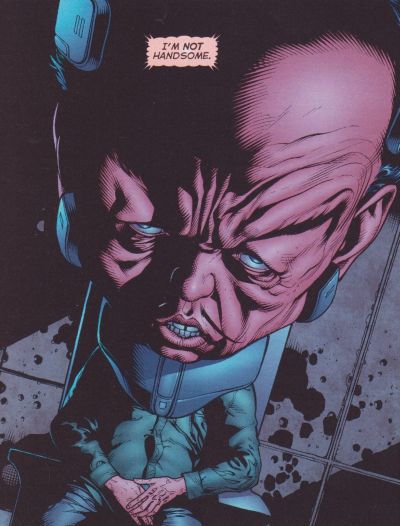

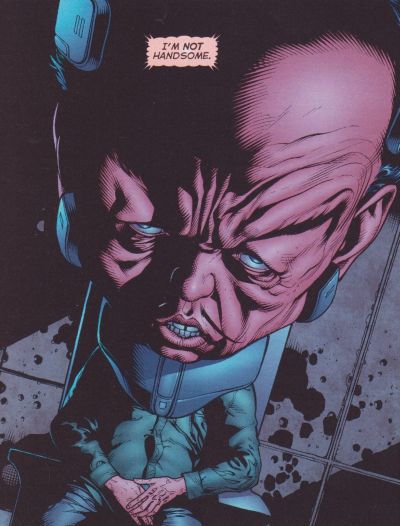

There’s also Hector Hammond, a gross, giant-headed scientist who Johns attempts to turn into a creepy, telepathic riff on Hannibal Lector, sitting in a prison cell and making cryptic comments to Hal, while commenting that Hal is so cool and he’s Hal’s biggest fan in an apparent attempt to replicate the creepiness of Frank Miller’s take on the Joker in The Dark Knight Returns, but without all that icky homoeroticism. He actually provides one of the more morally troubling moments in the series, but not in the intended way; Hal, while trying to get some information out of him, uses his ring to enable the pain centers in his giant brain, and then proceeds to beat him savagely:

Interrogating prisoners by beating information out of them is a pretty common practice in action movies and detective fiction, but that doesn’t make it any less morally troublesome (especially considering the still-continuing debates in U.S. politics about torturing prisoners), and having a guy dressed in green tights bloodying a giant-headed freak just cheapens the whole issue. It should be embarrassing for everyone involved, if only they had any shame.

Hal also faces some Manhunter robots (who have their own long backstory, but it’s not worth going into), which want to exterminate all life or something. There’s a subplot about the government trying to reverse-engineer alien technology, and these Manhunter guys come calling, giving Hal someone to fight, which leads to an especially silly battle in the sky over Coast City, in which a robot sucks all the power out of Hal’s ring, but he chases it in a fighter jet, and even though he promises to return it to the Air Force without a scratch, he promptly crashes it (he somehow manages to crash pretty much every plane he flies, making him the worst pilot ever), then gets his power back by reciting the Green Lantern Oath (which is how he usually recharges the ring from his own portable lantern; this is a pretty serious design flaw in the Manhunter robot), and the super-powerful machine is defeated when some rubble from the plane it just destroyed hits it on the head.

That’s how most of these plots work themselves out, by taking leaps that really don’t make any sense. In a later story, Hal and a couple of his fellow pilots get shot down over Chechnya and spend a few months in a prison camp, all because he likes to court danger by not wearing his ring when he flies. That’s a dumb way to start a plot, even if it’s already been established that Hal is a thrill-seeker and a doofus, but there are a hell of a lot of super-people who should have rescued them at some point. The Justice League shows up and apologizes, saying that they thought he was off in space, but none of his fellow Green Lanterns (three of whom are also from Earth) thought to check up on him when he went missing? It’s all meant to give him something to angst about (since he could have saved them all in minutes if he was wearing his ring), and maybe to plug some real-world threats into the book, but it takes some serious mental contortions to even attempt to accept.

And then things get dumber when Cowgirl, one of the pilots that got shot down along with Hal (and a sexy blonde chick that immediately falls for Hal, of course), gets the chance to fly a mission and avenge herself on the Chechen terrorists, and is promptly shot down again (the Air Force being rather carefree with their planes). Hal goes back to save her, and he’s not messing around this time:

That image is supposed to be awesome and badass, but it makes Hal look like an idiot, since he has already flown over the terrorist camp, but he’s still shooting, presumably into the air. He then gets involved in a tiresome international incident, leading a bunch of brainwashed superheroes and a bunch of Russian soldiers wearing robot armor to attack him, along with some bounty hunters, and even the rest of the Justice League. Amusingly, all these guys get into a big battle, but Hal wanders off to keep looking for Cowgirl, and everyone else apparently decides to just go home, since that’s the last we see of them.

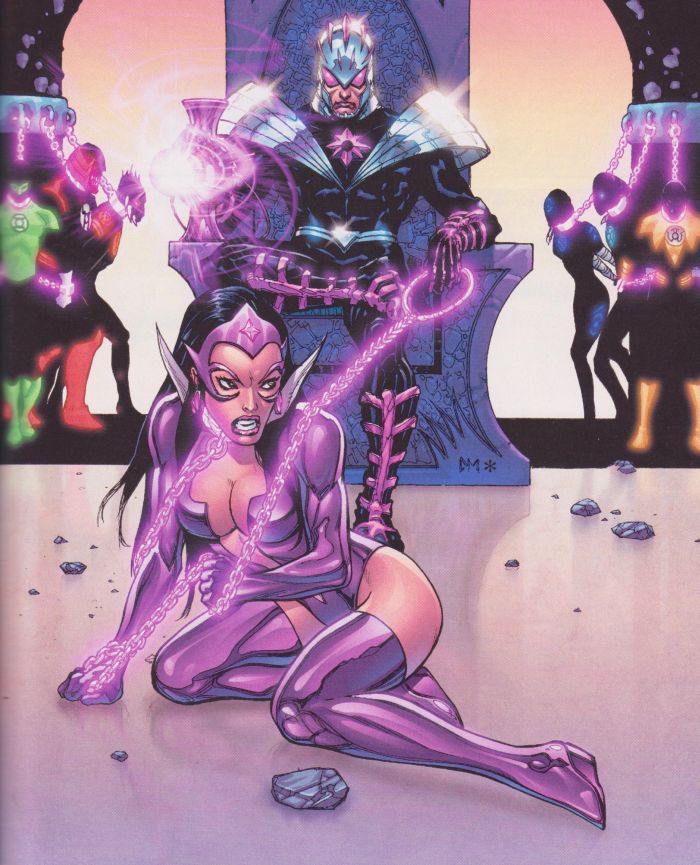

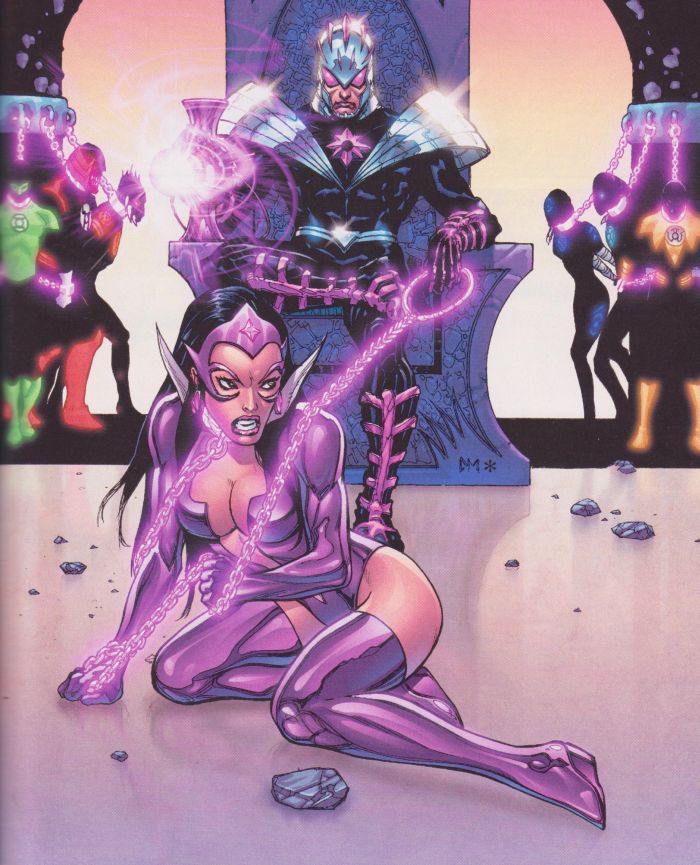

Then it’s time to reintroduce another villain: Star Sapphire, whose redesigned costume has been the target of much ire. This involves Hal’s ex-girlfriend, Carol Ferris, who was possessed by an alien crystal and became a villain, but this time around, the crystal, which is sent by an alien race called the Zamarons, alternates between Carol and Cowgirl, and it wants to mate with Hal, because he’s so awesome, all the ladies want to get with him, even the alien ones (who still have the voluptuous physiques superhero fans crave, making interspecies love cool and sexy instead of weird and creepy). It’s rather embarrassing to see so much love directed at the dumbass hero, as if Johns has a total crush on him and tries to act it out through his sexy lady characters. There’s a bunch of nonsense about the Zamarons being avatars of love, but their version of love involves being very possessive and controlling, and they like to cover entire planets with stasis-inducing crystals, because they love them so much and want to protect them. Geoff Johns obviously has some issues with women.

So now that Johns has reestablished Green Lantern, reintroduced a bunch of the supporting cast, and tried to ground the character in something approximating the real world, he promptly takes off into the stratosphere and shifts the focus to large-scale outer space conflicts.

Part 2: Johns Gets Too Big for His Britches

Johns began hinting at ideas like “the emotional spectrum” and “the blackest night” in earlier issues, but he really kicks that stuff into gear in “The Sinestro Corps War”, a long storyline that sees the villainous Sinestro, a former Green Lantern who went bad, start his own lantern corps, tinted yellow and powered by fear. That is, they inflict fear, because they’re a bunch of scary monsters and evil murderers, and they want to kill all the Green Lanterns. This leads to a series of violent fight scenes, with lots of characters on both sides being viciously killed. Johns tries really hard to sell the scale of the threat, with Sinestro recruiting big-time villains like the Cyborg Superman (the villain behind the infamous “Death of Superman” story of the 90s), Superboy Prime (an evil version of Superboy from an alternate universe that was the villain of the Johns-written event crossover Infinite Crisis), and the Anti-Monitor (the reality-destroying villain of the crossover that began them all, Crisis on Infinite Earths), and he has Kyle Rayner, the guy who replaced Hal as Green Lantern when he was evil/dead, get possessed by the fear entity Parallax (the one that turned Hal evil), which gives him a monstrous evil grin/sneer, along with some other especially grotesque (and kind of Freudian) visuals:

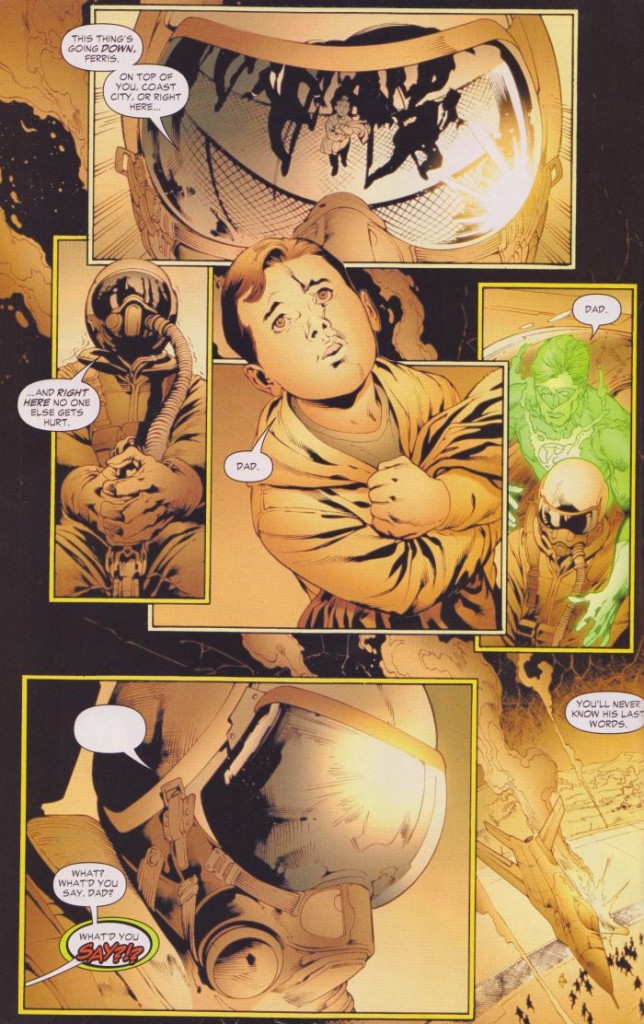

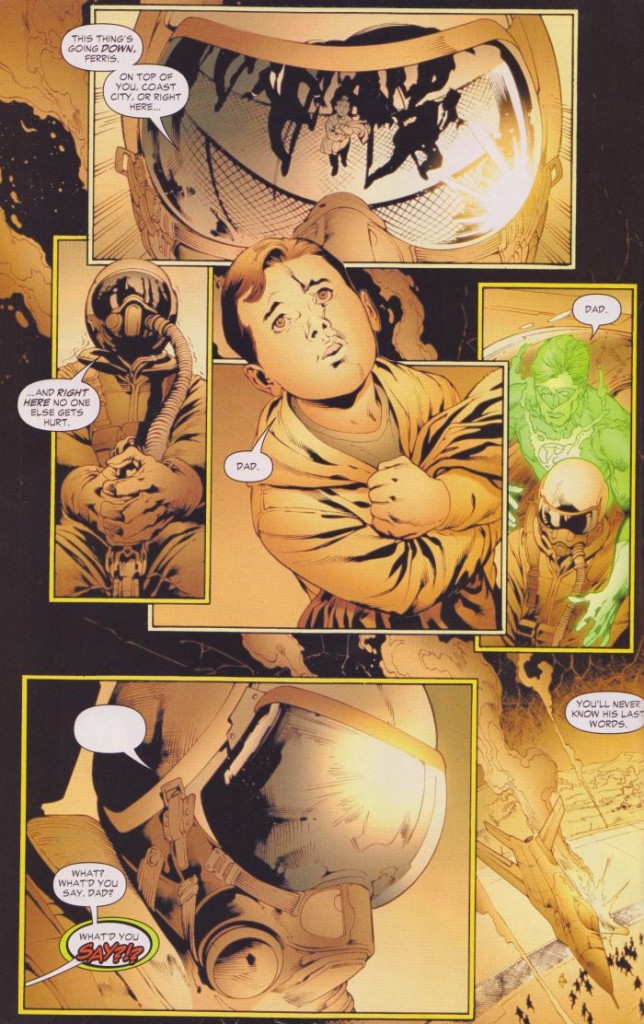

This is actually one of the more innocuous stories in Johns’ tenure on the series, since it’s pretty much non-stop, large-scale action, with the Sinestro Corps attacking Oa (the Green Lanterns’ headquarters), various lanterns attacking the Sinestros’ headquarters (including a scene in which Hal steals a bunch of yellow rings, for little reason other than to recreate the cover of the issue where he went crazy and killed everyone), and everyone converging on Earth for a big smackdown, which the Green Lanterns win when the Guardians (the little blue dwarves who are in charge of all the Green Lanterns) rewrite their laws in order to allow the use of lethal force (which turns out to be Sinestro’s plan, since he just wants to bring fascist order to the universe, and the deployment of lethal force is key to doing so). The relatively straightforward nature of the story doesn’t stop it from including all sorts of idiocy and tastelessness though. For one, Sinestro manages to get Parallax to possess Kyle Rayner by revealing that his (Kyle’s) mother was killed by a member of the Sinestro Corps who is a sentient virus. Why that makes him scared rather than angry is unknown. Dumber still is a scene in which we learn Hal’s greatest fear, which is that he’ll never know what his father’s last words were:

Does that even make sense? What a weird thing to be scared of. That’s pretty typical of Johns though; he tries to work in dramatic moments that fit the themes he tries to write about (in this case, “fear”), while constantly mashing on the buttons labeled “Hal is awesome and everyone loves him” and “Hal wanted to fly just like his father”. The most cringe-worthy moment in this entire story comes when Sinestro and his minions are attacking Coast City, and Hal broadcasts a notice through everyone’s TV to evacuate the city for their own safety, but the people have learned through his example to have no fear, so they all stay and shine green lights through their windows to show their support. Aside from the question of why everyone has green cellophane lying around their houses, they’re just being really fucking stupid, intentionally putting themselves in harm’s way and giving the bad guys targets to use against the Green Lanterns, all as a meaningless gesture.

The rest of the battle is all pretty fine, aside from regular bits of ultraviolence and other such ridiculousness thrown in on both sides. It’s a pretty gleeful orgy of killing, with background characters regularly chopping each other’s heads off and tearing each other in half. The cover of one of the issues shows the Statue of Liberty being replaced by a statue of Sinestro, but it’s not meant to be symbolic; one of the first things the bad guys do after attacking Earth is build a big Sinestro statue, since they have weird priorities. The bad sentient virus infects Guy Gardner (another Green Lantern from Earth), but he is saved when a microscopic Green Lantern enters his bloodstream and rescues him. Amusingly, the Cyborg Superman just wants to die, and when it looks like he’s going to get his wish, a single tear emerges from his one human eye and rolls down his cheek. And while this moment isn’t written by Johns, but rather Peter J. Tomasi in the sister Green Lantern Corps title, it’s definitely worthy of inclusion in a tallying of the story’s hilariously awful moments:

There’s also a scene in which Parallax manages to possess both Kyle and Hal at the same time, and they overcome it by looking at a painting that Kyle’s mother bequeathed to him (???) and crawl out of its mouth in a particularly disgusting scene:

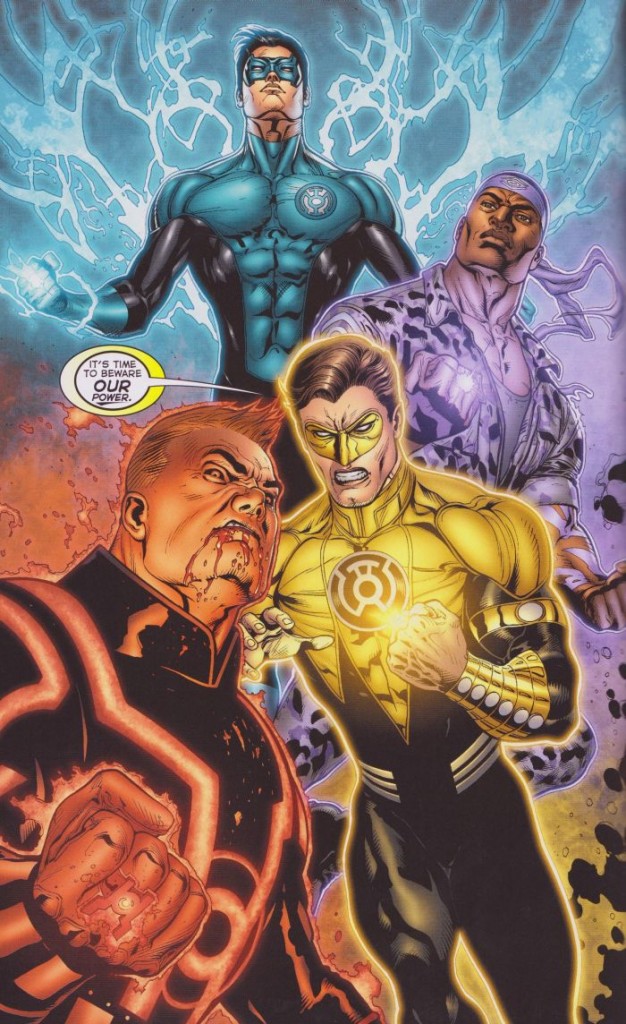

But the big, “important” moment of the story, a revelation that would shape the series from this point forward, is when we learn all about the “emotional spectrum”, a whole series of lantern corps that will emerge, beginning an epic “War of Light”. In addition to green for willpower (which Johns apparently thinks is an emotion), there’s yellow for fear (Sinestro’s corps), red for rage, orange for avarice (green, for envy or greed, would make more sense here, but it was already taken), blue for hope, indigo for compassion, and violet for love (the Star Sapphires). And so begins the simplification of all emotion down into a small number of possibilities (what about happiness, despair, betrayal, regret, or, I dunno, nostalgia?), creating fodder for innumerable stories in which different colors can fight each other with a “my hope shall overcome your rage!” simplicity to their actions. As dumb as this idea is, it’s a concept that could work well enough for kiddie entertainment, like something out of Care Bears or My Little Pony, but wedding it to regular maimings, the constant spilling of blood, ridiculously-proportioned women thrusting their secondary sexual characteristics at the reader, and teeth-gritted angsting about law and justice turns it all into a loud, garish mess.

We also learn that this is all leading up to the zombie-riffic “Blackest Night” story, but we’ve gotta take a break first (lest the constant high-stakes mayhem become more exhausting than it is already), so why not run in place for a bit?

Part 3: Howsabout a Pointless Origin Story?

Yes, the main thing that comes in between “The Sinestro Corps War” and “Blackest Night” is “Secret Origin”, a revised retelling of how Hal first became a Green Lantern. It’s pretty much a redo of the story we’ve already heard several times over (since this is superhero comics, it gets recapped every few issues anyway), with changes to make it more directly relevant to the stories Johns is currently telling. For instance, when Abin Sur, the Green Lantern who crashed his spaceship on Earth and gave his ring to Hal Jordan, was flying to Earth, he was bringing along a murderous alien called Atrocitus (yes, that’s really his name; Johns is amazing at coming up with the most obvious names possible for bad guys, including a member of Sinestro’s corps called Arkillo), for no reason other than to insert him into Hal’s origin story. Hal and Sinestro end up hunting him down, which inadvertently leads to the origin of the villain Black Hand when he comes into possession of a “cosmic divining rod” (a device that sucks up Green Lantern powers and then shoots them back out as death rays) that Atrocitus built. For a couple of space cops, Hal and Sinestro do a remarkably poor job of containing stray weapons.

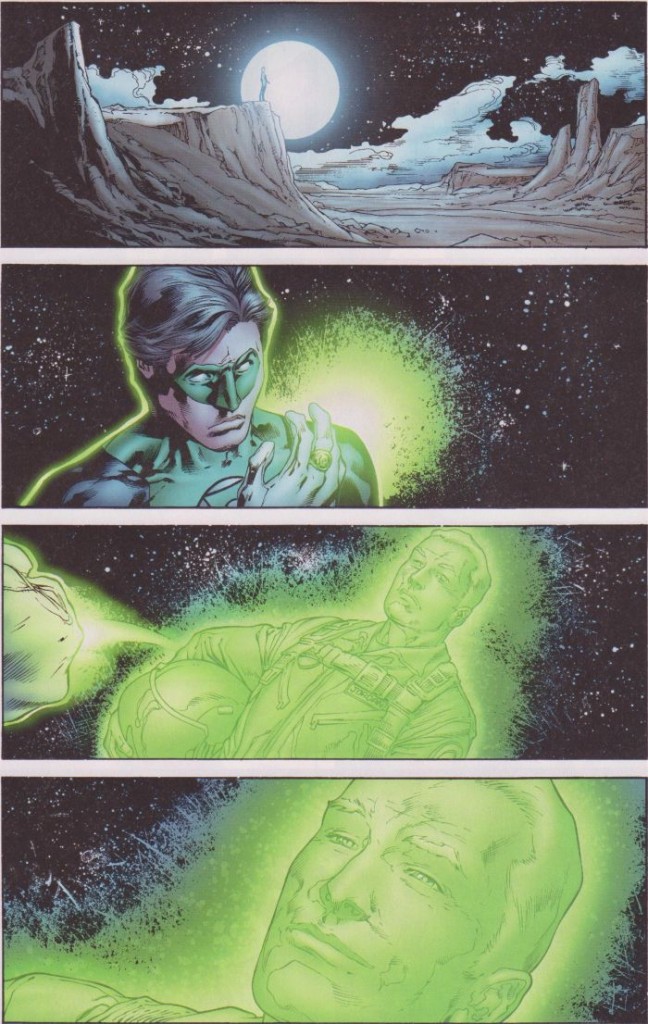

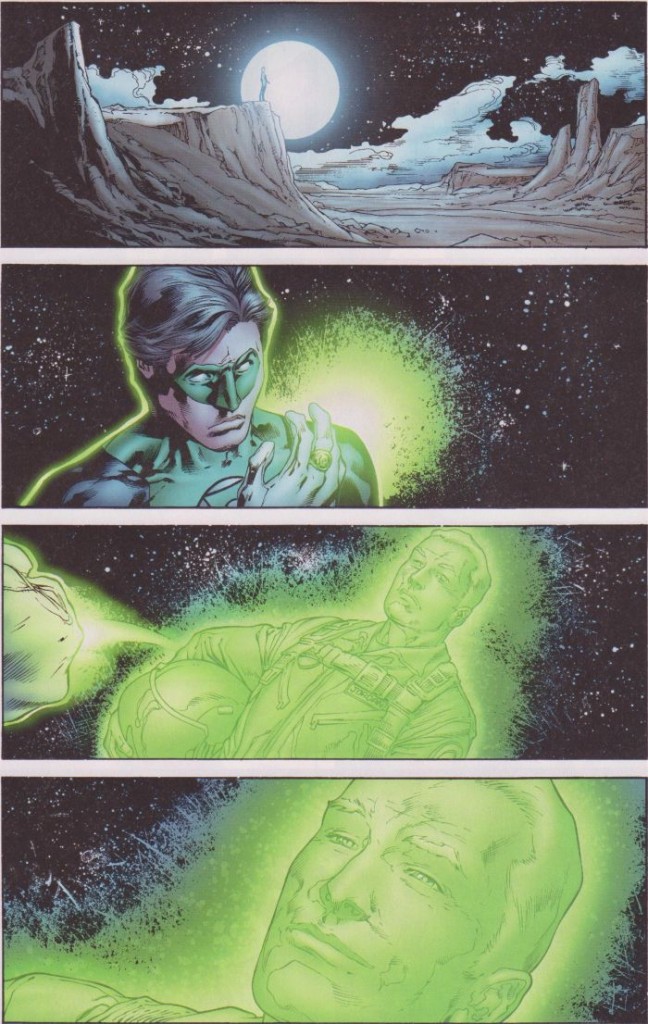

The best (that is, most hilariously ham-fisted) moment of this origin story comes when Hal decides to hunt down Carl Ferris, the man who ran the aeronautics company his father was working for when he crashed his plane and died, because he’s sure that Ferris murdered his father. But it turns out that his father’s death destroyed Ferris, and his guilt and sadness has driven him to get cancer, leaving him on his deathbed. Oh, such misdirected anger! This leads Hal to sit on some remote mountain bluffs and use his ring to create an image of his father in order to have it smile and give his approval:

So there’s the real reason for the flashback: dealing with daddy issues. Back in the present, Johns introduces the Red Lanterns, who are led by Atrocitus, who is now boiling over with rage and seeking vengeance on Sinestro. These guys are the ones that gave us several especially atrocious covers, the likes of which keep driving customers from comic book stores, and they’re kind of the point at which Geoff Johns tips over into self-parody. The anger powers of the Red Lanterns manifest themselves as acidic blood that they projectile vomit at their enemies, which is rather disgusting. They’re presented as mindless minions of Atrocitus, barely able to keep themselves in check, and their ranks include a kitty cat for some reason, since I guess cats are known for holding grudges or something. In their introduction story, Sinestro, who was captured by the Green Lanterns at the end of the “Sinestro Corps War” storyline, is scheduled to be executed, but they decide to have it done on his home planet, which is a really stupid idea, since transporting him anywhere makes an easy opening for attack. And sure enough, that’s what happens, with some Sinestro Corps members trying to free their leader, but everyone being overtaken by some Red Lanterns, and Hal being sent to save him, or possibly execute him himself, whichever happens first.

This also necessitates the introduction of the Blue Lanterns, whose emotion is hope, which doesn’t really make much sense. What is hope, anyway? The desire for something good to happen? A belief in some sort of god? Is that even an emotion? And how do Blue Lanterns control this hope? Do they feel it themselves and wish really hard that they can blow shit up, or do they have to channel it from other believers? In fact, there are tons of inconsistencies in these emotional powers; Green Lanters are super-willful, so they channel their mental forcefulness into making big green weapons, and Red Lanterns are so angry that they just boil over with explosive bile, but Yellow Lanterns don’t feel fear, they inflict it. So how do they make all sorts of yellow stuff, by being super-scary? If whoever they are fighting isn’t easily frightened, are their yellow force bubbles completely ineffective? Later, we learn about compassion, its main power being that it is able to channel the other emotions and emulate them. That seems to be taking compassion as synonymous with empathy, but if that’s the case, is it even an emotion? Would anybody describe compassion as the emotion of being able to feel other emotions? And how do the various lantern corps use their powers anyway? Do they love, or hope, or covet so hard that they create objects out of their color-coded energy? What if they’re not feeling especially angry or scary that day? Do they have to be completely single-minded, focusing only on their specific emotion, to be able to do anything? Obviously, thinking too hard about this nonsense is a path to frustration and insanity, but Johns never stops delving into the intricacies of this silly system he set up, which makes the inconsistencies and poorly-thought-out ideas impossible to ignore.

Whatever the case, the Blue Lanterns include an alien named Saint Walker, and an elephant alien who is meant to be a stand-in for the Hindu god Ganesh, demonstrating that hope is meant to stand for religious belief, which Johns simplifies into meaninglessness with their oft-repeated catchphrase, “All will be well”. These guys power Hal’s ring up to 200% capacity and tag along with him to rescue Sinestro, but they get to demonstrate how great they are along the way by cooling down a star about to go supernova, saving all the inhabitants of the planet revolving around it. Interestingly, this is one of the only times in the entire series that any of the Lanterns perform their (or at least the Green shade of the spectrum’s) stated mission to patrol space, fight crime, and help people out. The rest of the series is all about people attacking Hal because they are obsessed with him, or engaging in power struggles between different colors. By including a simple moment like this, the entire premise and conflict of the series is thrown into relief, seeming like petty infighting between the powerful, who ignore the plights of those not worthy of their attention. This wouldn’t be a bad metaphor for modern society, if it was at all intended as such.

So anyway, Hal and pals go fight some Red Lanterns, and it’s really gross, full of vomit and gore, but the big moment comes when Hal gets a red ring stuck on his finger, turning him into a blood-vomiter, and then a blue one, which makes him some sort of Green/Red/Blue Lantern, since he’s so awesome he should get all the rings. There are more silly adventures, but it’s really just setting the stage for the next big crossover, which is about as Johnsian as they come.

Part 4: Geoff Johns Doesn’t Really Understand Zombies

Zombies can be used as a metaphor for any number of things, such as the inevitable approach of death or the assault of conformity, but when Geoff Johns came up with his zombie lantern epic “Blackest Night”, which stretched beyond the Green Lantern series to encompass the entire DC universe, he didn’t appear to put any thought into it other than that undead creatures are cool-looking, and maybe kind of scary because they’re unstoppable. In this form, as a bunch of deceased characters raised from the dead and turned evil when a swarm of black rings spreads throughout the universe and possesses various corpses, they’re kind of a creepy menace almost entirely through sheer numbers, but the menace of the huge, unstoppable army is kind of diluted, since we’ve already seen hordes of Sinestros, Manhunters, Red Lanterns, etc. attack our heroes. What should be effective imagery is already kind of tired, and the obnoxiousness of Johns’ zombies ruins most of the effect anyway. The best thing that can be said about the story is that it’s fairly effective as an example of large-scale action and that Johns seems like he might be attempting to make a statement about the ever-temporary nature of death in superhero comics, but if that’s the intent, it’s as muddled as all hell.

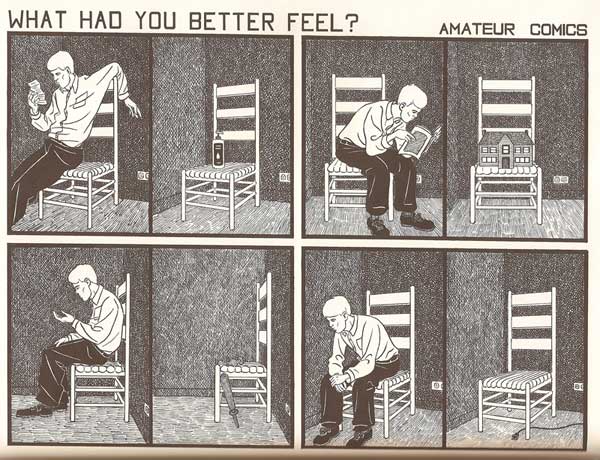

The main crime here though is the zombies themselves, which depart from the silent, brainless monsters of Dawn of the Dead and the like by being downright talkative. Johns is going for an assault on the emotions of the living heroes, having their dead friends and family returning and attacking them both physically and verbally. The thing is, these zombies never shut up. They are the most annoying fucking villains in modern superhero comics (and that’s saying something), trying to provoke the heroes by invoking their failures and assaulting them where it’s really supposed to hurt, then killing them as viciously as possible. Early on, Hawkman and Hawkgirl are attacked by Ralph Dibny (a.k.a. the Elongated Man) and his wife Sue (who, as a former happily married crime-solving team, have been some of the most debased characters of the last decade or so of superhero stories, Sue’s rape and murder being the centerpiece of the much-lamented story Identity Crisis), who taunt them crudely, then viciously murder them and tear their hearts out:

More of this sort of thing follows, with some especially egregious examples including zombie Firestorm attacking his replacement and torturing and murdering his girlfriend while forcing him to watch, or Jean Loring (Atom’s ex-wife, and the murderer of the aforementioned Sue Dibny) showing up to murder some heroes and scream such classic lines as “No one ever believed in him. Not until you came along tonight. And that glimmer of hope you ignited in him tasted so good.” It’s all rather gross and nasty, and while it’s meant to be shocking, it’s really just tiresome. As we learn, it’s all part of the main villain’s scheme, which requires the zombies to provoke emotions, which will then power him up for his attack on Earth. How this makes any sense is beyond me (why does a master of death need to drain emotions? What do emotions have to do with death at all, except as a way to connect this nonsense to Johns’ ongoing color-war plot?), and the scenes of zombie attacks are eye-rollingly dumb, as various characters are seen via zombie-vision to glow with whatever color on the “emotional spectrum” corresponds with whatever single emotion they are currently feeling, thus allowing the zombies to steal those colors when they kill them. It’s sheer stupidity, but while it drives the early chapters of the story, it’s mostly forgotten when Nekron, some sort of death god and the true villain behind the black lanterns, rises and starts his attack, eventually revealing that his real target is “the Entity”, the spirit of life, which was hidden within the Earth billions of years ago.

During all this, Green Lantern goes on a quest across the galaxy to unite all the different color rings as an attack against Nekron. He picks up his old girlfriend Carol, who is now a Star Sapphire wielding the power of love and wearing a skimpy costume; Sinestro; Saint Walker; Atrocitus; Larfleeze, a warthog-like alien who has the orange-tinted power of being greedy and saying “Mine!” a lot (which is supposed to be funny, but is just really annoying); and Indigo-1, the leader of the compassion-shooting Indigo Tribe, who get introduced as a bunch of mysterious, loincloth-wearing, gibberish-talking aliens in the middle of all the zombie chaos. Their attack on Nekron doesn’t work though, because Johns needed to drag the plot out some more, so they spend a few more issues fighting zombies, while Hal ends up getting willingly possessed by Parallax again so he can fight the Spectre, the spirit of God’s vengeance (who takes the form of a giant, pale guy wearing a green cloak and underwear), who was somehow also turned into a zombie, and then Nekron possesses all the heroes who have died and been resurrected at some point, like Superman, Wonder Woman, and Green Arrow. The Barry Allen version of the Flash, who had recently been brought back to life some twenty years after he died in the original Crisis on Infinite Earths, and Hal Jordan manage to escape being possessed though, because they’re Johns’ favorites.

And then, in an especially silly plot point, somebody reveals that all the different rings are based on Oan technology (even though, as we saw in previous stories, some of them apparently manifested spontaneously through accumulated emotion or something), and the “Book of Oa” (a giant book that the Guardians keep around, because that’s how billion-year-old guys with unimaginably complex technology would store a repository of their laws and history) states that during “the blackest night”, which had been prophesied for thousands of years, Green Lanterns can deputize somebody else for twenty-four hours. This is an excuse for all the colored lanterns to recruit another character to their teams, and for the artists to come up with new costume designs for familiar characters. So, Flash becomes a Blue Lantern (he has a lot of hope, I guess), Atom becomes a member of the Indigo Tribe (because Johns established him earlier in the story as being especially compassionate, showing that he didn’t blame his murderous ex-wife for her crimes), Mera (Aquaman’s wife, who Johns has decided is an important character) becomes a Red Lantern, Wonder Woman becomes a Star Sapphire (mostly so she can get a skimpier version of her costume), Batman villain the Scarecrow becomes a Yellow Lantern (his deal is that he gives people a drug that brings their nightmares to life, although Johns makes him a fear-addict here so he can be all crazy with the yellow fear powers), and Superman’s arch-nemesis Lex Luthor becomes a greedy Orange Lantern.

As with most of Johns’ comics (and superhero comics in general, really), this is action figure storytelling, grown men playing with toys and trying to think of cool playsets to build and different childish conflicts for them to get into, but while that sort of thing can have its charms (most Hollywood action movies aren’t much different), Johns turns it into a distasteful exercise in arrested development, trying desperately to make it serious and dark and violent and “adult”. Hence the nasty stuff with the zombies, the constant sexualization of any female characters (even the weird alien ones), or the more ridiculous stuff he comes up with later, like a scene in which zombie Aquaman presents Mera with a reanimated version of their dead baby, and she vomits red blood-acid all over it:

Even dumber is when Johns uses the revelation of the white Entity as a chance to combine his color-coded emotion system with Christian mythology in a retelling of the origin of life that incorporates all the nonsense he created over the course of his years of color-based storytelling, casting the orange power of avarice as the snake that influenced Eve in the Garden of Eden, showing how Cain’s murder of Abel birthed the red power of rage, and so on. It’s so idiotic as to be kind of daringly subversive, or so I might think if I didn’t believe that Johns takes it all very, very seriously.

The good guys win in the end, of course, although there’s at least one hiccup along the way when Sinestro assumes the power of the Entity and becomes a White Lantern. But he can’t control it, and Hal ends up being the one who defeats the power of death by uniting all the other resurrected heroes and then bringing Nekron’s sidekick back to life, causing him to vomit up a bunch of white rings and destroy Nekron. At least, I think that happens; it gets pretty hard to follow, as usually happens with this cast-of-thousands clusterfucks. There’s some business about various dead heroes being resurrected for some mysterious purpose, which led into another series called Brightest Day that I don’t think I can bear to inflict upon myself after this much Johns exposure. I think the big mystery turns out to be the return of Swamp Thing though, but a version of the character that does its best to negate any changes wrought upon the franchise by Alan Moore, since Johns, ever loyal to his employers, knows which side his bread is buttered on.

Part 5: Oh God, This Just Keeps Going

Uniting everyone in the universe to shoot a bunch of colored beams around and defeat death itself is only a stop along the journey for Johns, who just keeps trucking along with his candy-colored epic, doing his best to inflict sensory overload on his readers through more and more battles between feelings. The next phase of the story sees Hal and friends seeking out the “entities” of all the different lanterns, the various spirits that embody the emotions behind the colors, in an attempt to keep them from falling into the wrong hands. It’s as misguided and weird as ever, including at least one perfect example of Johns’ dunderheaded take on what are supposed to be the basic building blocks of the human experience. That would be the fact that the love entity is a vicious monster called the Predator (did I mention that Johns must have had some relationship problems at some point?) who possesses a stalker guy and turns him into a nasty killer. And of course, the male version of a Star Sapphire gets to wear a head-to-toe costume that puts him into pretty striking contrast to the flesh-revealing scraps of fabric(?) that barely cover his female minions:

Johns even tries to have his cake and eat it too, by having Carol complain about having to wear a swimsuit while fighting evil across the universe (even though other Star Sapphires are shown as wearing versions of the costume that aren’t as revealing) and including a scene in which she bumps into a guy on the street who spills a drink on her boobs and then leers at her along with his fellow frat boys, as if we’re supposed to frown upon that objectification of women, then ogle the cleavage pushed into our faces a few pages later.

In other nonsense, Atrocitus searches for his own rage entity, which is a giant bull called the Butcher. Let me repeat that: it’s a bull. Called the Butcher. Did nobody notice the irony there? Johns actually tries to make Atrocitus a sympathetic character, with his clumsy attempts at character development being pretty amusing as he comes across a prison full of murderers and just executes them all with his red vomit:

He also fights the Spectre in the middle of an execution, during which the man being electrocuted taunts his victim’s father, then gets all scared and sorry when the father gets possessed by the Butcher and turns into a vengeance-fueled monster. As much as Johns seems to want to use these emotion-colors to tell stories, he’s got nothing interesting to say about them, or any depth to any of his characters. The killer is unrepentant and evil, ready for death, but he still cracks and starts begging for his life when the various scary monster characters attack him. The father is sad and angry, and I guess we’re supposed to feel sorry for him as he cries and screams and turns into a killer himself. But there’s no attempt to address the morality of capital punishment or the effect that violent revenge might have on those who carry it out; it’s all just window dressing for aliens and costumed creatures to fight over who gets to wield power. Johns does seem to be trying to add some depth to Atrocitus’ character, making him a sad, tortured being under his raging exterior, but since he’s designed as a fanged, screaming, blood-puking monster, it ends up being pretty amusing when he tries to actually emote:

In other entity-chasing antics, Hector Hammond escapes from prison and gets possessed by Ophidian, the orange snake-monster of avarice; a girl who was kidnapped by a serial killer becomes the host of Adara, the hope entity that looks like a three-headed eagle for some reason; and a selfless paramedic gets a page or two to argue with a colleague over whether they should treat somebody who doesn’t have insurance before Proselyte, the giant octopus avatar of compassion (since octopi are the most empathetic of all the animals, of course), takes him over. But that gets ignored pretty quickly in favor of the introduction of a mysterious villain that turns out to be Krona, who has his own backstory that is much too tiresome to explain, even though it gets revisited several times over the course of the next bunch of issues. He’s a rebel Guardian, and he wants revenge, or he wants to rule the universe, or he wants to kill everyone, or there’s some other explanation and goal for his villainy, but it really doesn’t matter; he’s just the next big bad guy to fight.

So Hal and his multicolored buddies have to jet around the universe doing more ring-zapping, but not before he has a long, tiresome argument with the Flash about how he’s a jerk and impulsive and doesn’t accept help from his friends and doesn’t follow rules and blah blah blah, and Flash gets possessed by Parallax and they fight, and there’s an especially dumb discussion of H.G. Wells’ The Time Machine that I suspect Johns got from watching the Mel Gibson movie Ransom rather than reading the actual book. Hal turns down help from his friends in the Justice League because he’s too cool for them, and he goes off to space with his colored-ring pals, and they all get sucked into a giant book of forbidden Green Lantern lore, and oh god, this is so stupid, and it just keeps going and going and going.

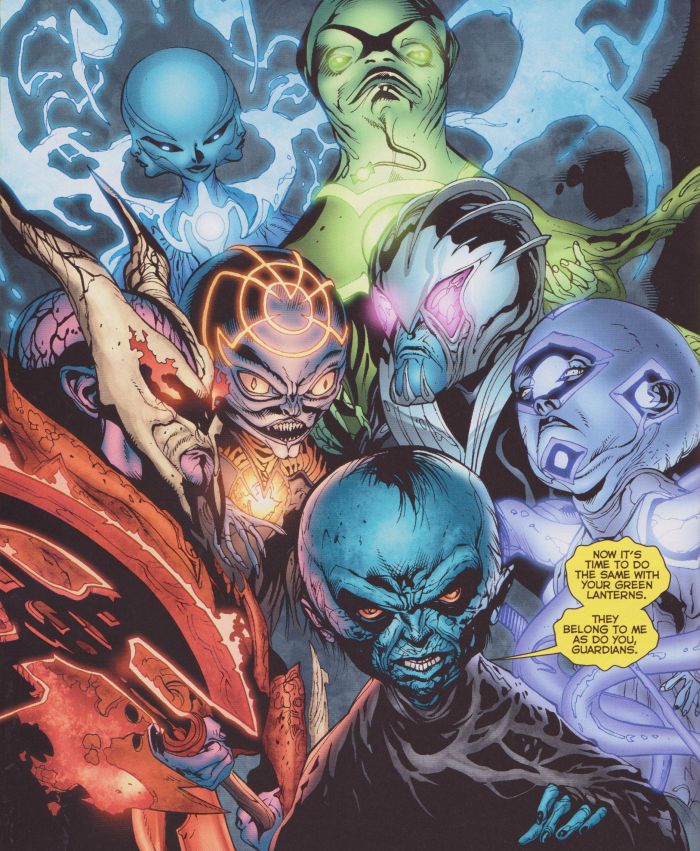

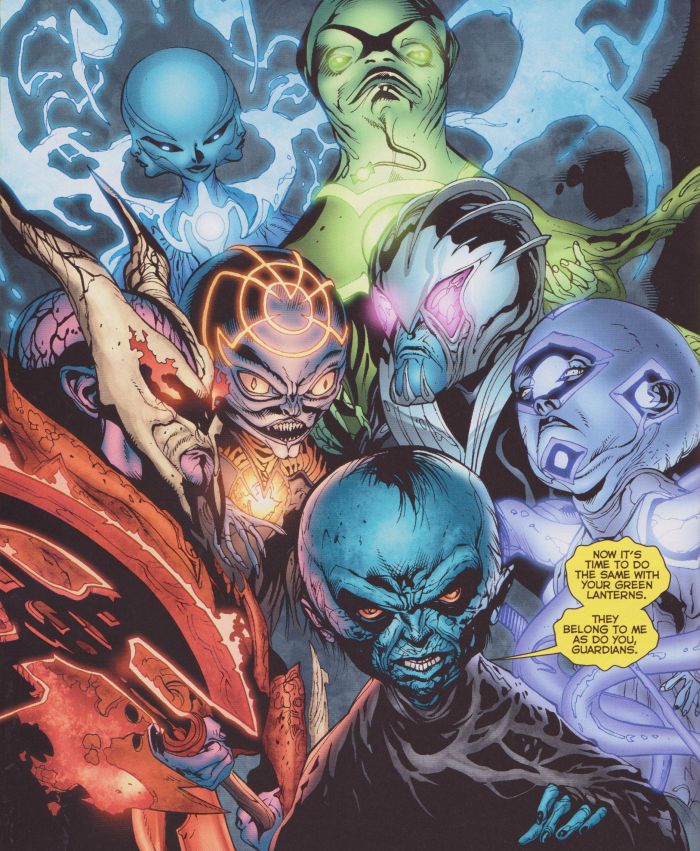

Actually, at this point, the series has reached a state of sublime stupidity, a childlike “and then this happened, and then this happened” sort of storytelling equilibrium, and while it’s certainly not good, it’s mostly readable, and one almost wants to keep plowing through it just to see what contortions to the rainbow-feelings cosmos Johns will come up with next. Krona takes over the Green Lanterns, cramming the different entities into all the Guardians and revealing some amusingly bizarre designs:

Then he brainwashes all the Green Lanterns, which forces Hal and the other human Green Lanterns to switch to different-colored rings. This necessitates more costume redesigns, including some especially awful purple camouflage fatigues for John Stewart:

Then Hal and Guy Gardner get captured, and Krona intends for them to get turned into Guardians, but that’s just a cruel tease, because who wouldn’t have wanted to see them as macrocephalic dwarves? Then there’s more fighting, and it all ends kind of suddenly (I suspect the story was compressed a bit in order to reach an end in time for DC’s latest universe-wide reboot) with Hal’s ring being taken away and Sinestro becoming a Green Lantern, and a final panel that I wish was the actual end of the series:

Of course, after the big “New 52” reboot, Johns picked up right where he left off, with more of the same characters zooming around space and arguing over rings and colors and Guardians, but this presents a perfect jumping-off point, enabling me to attempt to keep what’s left of my sanity after immersing myself in this moronic view of the emotional cosmos.

In Conclusion, If Anybody Is Still Reading

With this apparently being the maximum amount of Geoff Johns comics as I can take, I’m left with a few questions (mostly why I exposed myself to such mental toxicity) and observations. It seems to me that Johns, in an attempt to weave a grand, expansive cosmos around his favorite character, fundamentally misunderstood the basis of the idea behind it, and managed to turn it from sort-of science fiction into dorky fantasy, with an air of “sufficiently advanced technology seems like magic” legitimacy to it. The original concept behind Green Lantern is that the rings can create constructs of energy (or “plasma” or something, for writers who wanted to sound scientific), and mastering their use took a great deal of willpower, even if that’s a nebulous concept in and of itself. But Johns decided that the green energy itself <em>was</em> willpower, which, if he considered it an emotion, opened the gateway to a whole range of other emotions, and he extrapolated outward to a grand vista of colored feelings, a whole spacetime-spanning, multi-front war of shifting alliances, reversals, betrayals, and ever-more-grand-and-violent battles. That sort of massive-scale ambition is kind of commendable, and, sure, it could be a good basis for a kiddie cartoon of some sort, but Johns takes it all so damn seriously. He tries to retell the origin of life and address the nature of death and the afterlife. He has characters confront the horrors of genocide and debate the morality of capital punishment. He attempts to delve into the nature of “pure” emotions themselves and see how they can be manipulated, twisted, or channeled by people. This seems like it’s more than just a big spandex space opera to him; it’s a way of life.

That’s what ultimately sours me on the entire enterprise: the need to turn what could be dumb-but-enjoyable action-adventure stories into some sort of statement, even if that statement is just “look how mature and adult this is!” That’s the nature of superhero comics these days, adding sex (or hints in that direction, mostly consisting of skimpy costumes and cleavage/upskirt viewing angles for female characters) and violence (which is not nearly as coy, usually being front-and-center on the page and as gory as possible) to the children’s entertainment which the creators and the audience have such nostalgia for. Johns’ ambition in revamping and “maturing” the characters and milieus that he loved so much as a kid is obvious, but while he may have stumbled upon some halfway decent ideas and managed to put together some pretty good action sequences, the execution is so blunt and dumb, full of ridiculous nonsense and crammed with tawdry attempts to make the stories “dark”, that anyone in their right mind should just laugh, rather than celebrate him as some sort of master storyteller.

So what’s the big takeaway from this overlong exercise? Are Johns’ comics as terrible as I always thought they were? I’m tempted to say that they’re not, but that would probably be Stockholm Syndrome speaking. Really, they’re pretty awful from top to bottom, full of nonsensical twists and terrible dialogue (seriously, a little bit of wit would go a long way; instead, the stories are full of lines like “This rainbow rodeo’s locked and loaded!” and “I hope it still will be [enjoyable] when my foot’s up your wrinkled blue ass!”).

Some storylines are more palatable than others, with one big reason: the artist. Ivan Reis illustrates the majority of Johns’ tenure on the character, including the Blackest Night crossover, and he approaches the material in much the same way as Johns: seriously and reverently. His characters are all gritted teeth, bulging muscles, and staid heroism, which only exacerbates the pompous and “important” presentation of the whole stupid business. He does cram lots of detail into his pages, although this eventually gets exhausting; Blackest Night has what must be at least a half-dozen spreads of thousands of characters (zombie superheroes, zombie villains, Green Lanterns, more zombies, etc.) charging at the reader, to the point that all impact is lost by the time the story drags to an end. Doug Mahnke, on the other hand, brings a bit of humor and energy to the proceedings that other artists lack, providing enough exaggeration and strangeness as to make things occasionally seem more farcical and less self-conscious. He can’t completely overcome Johns’ stupidity, but he definitely makes it more enjoyable.

But no, some very minor redeeming qualities and backhanded praise aside, this is a collection of modern superhero comics that begs to be ignored and forgotten by anyone with half a brain. It’s certainly not the worst thing out there (just read a few issues of the Green Lantern Corps tie-ins that get packaged along with the main series in the compilation volumes to see stories that are uglier and worse-written), but it surpasses those lesser efforts through sheer influence. Somehow, Johns has determined how to push the nostalgia buttons of man-children like himself who can’t manage to expand the boundaries of their sphere of knowledge beyond stories of muscular behemoths in colorful, skin-tight costumes beating each other into oblivion, and he has shaped the industry to his liking, convincing everyone that this is how superhero stories should be told. It’s an impressive feat, especially considering that he doesn’t have the cleverness of a Joe Casey or Grant Morrison, the cult of personality of a Brian Michael Bendis or Warren Ellis, or the humanity of a Mark Waid or Kurt Busiek. Those writers might not be everyone’s cup of tea, but they’ve all proven themselves to be miles beyond Johns in creativity, style, and just plain comics-writing chops, but as so often happens in the world of commercial art, mediocrity rises to the top. But it doesn’t have to be that way. If, when presented with the chance to read Geoff Johns comics, we can all pledge to at least consider something else, something better, something that might not suck, then maybe, just maybe, this world will be a slightly less stupid place. Join me, if you will, in this goal: to lower the readership of Geoff Johns comics by .01%. We can do it, people!

__________

Click here for the Anniversary Index of Hate.