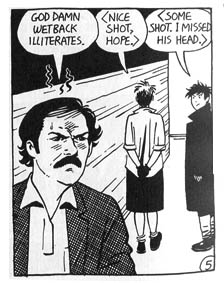

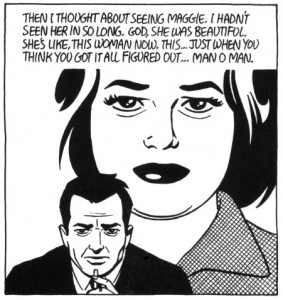

Whenever Jaime Hernandez decided (presumably in the shift from the “Mechanics” storyline to what would thereafter be identified as “Locas”) that his loosely linked narrative would unfold well into the future, and, more significantly, that he would mark that duration through the visible aging of his characters, his comics inevitably introduced operations of memory that would be experienced by both his characters and his readers. Most daringly, Jaime allowed his main character, Maggie, to gain weight as a sign of her physical aging, along with the many other changes in her relationships, location, and lifestyle (a term which might here refer to both her shifting sexual and musical preferences): such shifts represent what, outside of comics, we might call a life. It’s worth reinforcing how unusual this is in comics, which often employ a persistent present tense, in which characters never age; and only a comic of a certain duration (say, thirty years) will realize the full effects of this technique. By directly injecting chronology and temporality into his narrative (along the lines most famously pioneered by Frank King’s Gasoline Alley), Jaime brings the impact of the past on the present through directly into play.

Whenever Jaime Hernandez decided (presumably in the shift from the “Mechanics” storyline to what would thereafter be identified as “Locas”) that his loosely linked narrative would unfold well into the future, and, more significantly, that he would mark that duration through the visible aging of his characters, his comics inevitably introduced operations of memory that would be experienced by both his characters and his readers. Most daringly, Jaime allowed his main character, Maggie, to gain weight as a sign of her physical aging, along with the many other changes in her relationships, location, and lifestyle (a term which might here refer to both her shifting sexual and musical preferences): such shifts represent what, outside of comics, we might call a life. It’s worth reinforcing how unusual this is in comics, which often employ a persistent present tense, in which characters never age; and only a comic of a certain duration (say, thirty years) will realize the full effects of this technique. By directly injecting chronology and temporality into his narrative (along the lines most famously pioneered by Frank King’s Gasoline Alley), Jaime brings the impact of the past on the present through directly into play.

While the treatment of memory in comics may be most fully evident in comics memoirs, which (at least since Art Spiegelman’s Maus) have often employed sophisticated formal means to represent relationships between present and past on the static page or, often, to collapse temporal gaps in order to render powerful, often traumatic, memories, the play of memory has in fact been central to mainstream comics as well, particularly following the rise in significance for readers and creators of what fans now summarize as “continuity.” DC’s company-wide Crisis on Infinite Earths (1985) was not only an attempt to clean up the company’s messy and contradictory history, but, more audaciously, a bid to wipe clean the memories of longtime DC fans. But powerful memories aren’t effectively repressed, especially by corporate design or external control. A poignant Deadman story by Alan Brennert, tucked away in Christmas with the Super-Heroes 2 as soon as 1988, suggested that the outrageous notion that post-Crisis readers were simply expected to forget the prior existence of an “officially” eliminated character like Supergirl Kara Zor-El was simply unenforceable. Indeed, the rise of comics fandom (and collecting) was built upon acts of “unofficial” collective memory which rendered DC and Marvel’s loosely connected series as linked serials, transforming semi-autonomous pulp fictions into something like tribal chronicles devoted to (somewhat) logical unfolding and overarching narrative sequence. By 1990, when Grant Morrison retrieved the Psycho Pirate (also ostensibly banished from revised DC history) for his self-reflexive run on Animal Man, the supposedly forgotten DC multiverse came roaring back in a flood of tears (the cover of Animal Man 24 depicts the Psycho Pirate literally weeping old DC comics), with Morrison’s subsequent work for DC dedicated in large part to remembering rather than forgetting ever minor character or event in the company’s history. (DC’s previous injunction to forget has in large measure been turned into a demand that loyal readers, like Morrison, remember everything.)

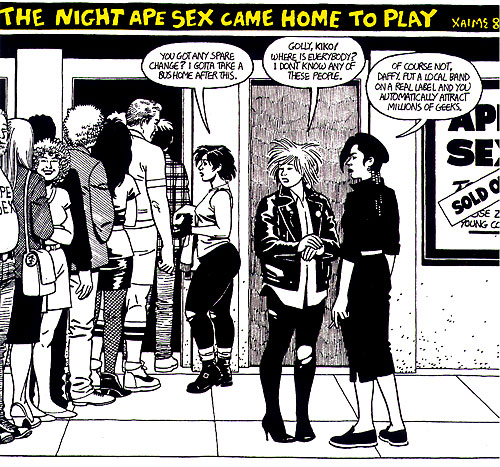

While Jaime Hernandez’s work at times draws upon (usually with parodic affection) the sort of continuity that now undergirds superhero comics, the chronology he more fully employs is closer to the plotting of soap operas or other long-form narratives that may have created without master plans, especially those like long-running television serials or film franchises (begun without conclusions in mind) in which creators must not only keep the narrative ball rolling, but account for the actual bodies of actors playing characters visibly aging before the eyes of their audiences. While superhero narratives now imply that their accumulated events unfold in time, most still have to figure out fantastic (or spuriously scientific) reasons for their main characters’ slow or halted aging despite the passage of time such comics otherwise exploit by drawing upon what had seemed long-abandoned threads. While “Locas” might easily be criticized for lacking a tight coherence across its full span (a criticism I find misapplied to a work that thrives on the fragmentation, improvisation, and spontaneity of punk rock, among Jaime’s more obvious aesthetic models), Jaime has increasingly relied upon a narrative unfolding which is simultaneously ragged and intricately woven (images that recall the original meaning of a “text” as a weaving), often moving forward by leaping back (though flashbacks) or, in his most recent work, through what appears to be an audacious leap into the future. This structure seems willfully incoherent at times, yet increasingly committed to exploring the ability of memories, whether vivid or half-forgotten, to deepen the impact of successive stories in his series. There are clear narrative (and commercial) risks involved in this strategy: Jaime’s work increasingly rewards loyal, long-time readers and is therefore perhaps less and less inviting to newcomers. (The same is true of most mainstream superhero comics, despite weak attempts to reach new audiences through reboots and relaunches every so often.) As a reader who has been with Love and Rockets over the long haul, my own response to the developing “Locas” stories is deep satisfaction and emotional reward in what seems to me one of the richest reading experiences in the history – that is to say, historical experience – of comics.

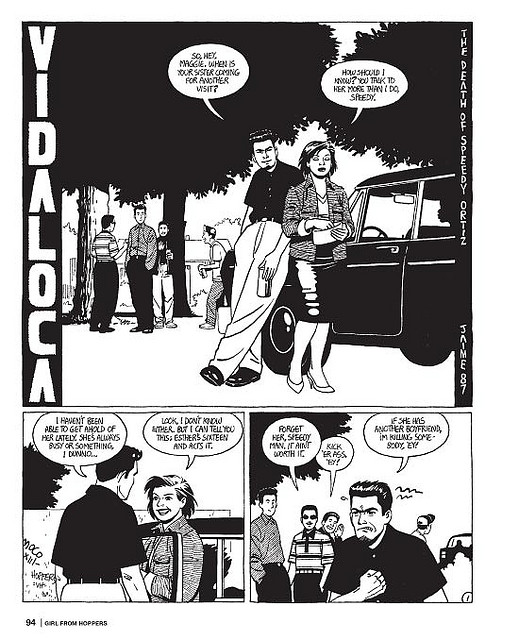

For instance, much of the general narrative context for the recent and lauded “Browntown” from 2010 derives from a summary of the Chascarillo family’s circumstances by Speedy Ortiz within a single panel of the 1984 story “Locos.” In a following story, “Young Locas” from 1985, Maggie’s best friend Letty’s death was announced, with a (drawing of) a photograph (reminiscent of the notable use of photographs in comics memoirs such as Maus and Fun Home: as Susan Sontag famously claimed, “all photographs are memento mori.”). That early story and traumatic event will be narrated from Letty’s perspective and more fully depicted in 2011’s “Return for Me.” (And “Browntown” and “Return for Me” function as flashbacks of a sort in relation to the five-part “The Love Bunglers” that surrounds them in the two most recent volumes of Love and Rockets.) The full impact of each narrative, in other words, relies upon the invocation of the reader’s memory across the gap of a quarter-century. Only an artist who has established an exceptionally loyal readership (or obsessive re-readership) can perhaps get away with such literal suspense, leaving readers hanging for more than two decades. Again, it seems inevitable that a new reader (who may still appreciate Jaime’s considerable skills as an artist) simply won’t have access to the long-term effect such connections have for others.

Insofar as such instances rely upon a long memory (or, more realistically, re-reading), they seem appropriately attached by Jaime to traumatic events, which are commonly understood (in the now vast literature on the representation of trauma in various media) as unassimilable when they occur. Trauma is typically experienced as a delayed response, in the process Freud termed Nachträglichkeit, or “deferred action,” which recognizes not only a delay in full understanding, but assumes a revised understanding of an earlier event in light of later circumstances and the clarity or obfuscation provided by retrospection. (Lacan translated the term as après-coup, like Freud’s German term more commonplace in French than the typical English translation, which sounds a bit technical. Both psychoanalysts wished to convey the common experience of such temporal disruptions to psychic life.) While the suspense – again, the quite literal suspension of narrative resolution through delayed narration – Jaime has built into his narratives may seem to ask a great deal of readers seeking more autonomous or self-enclosed episodes, the gaps he sustains may be more accurate representations of the way in which traumatic memories function than more efficient and concise narratives provide.

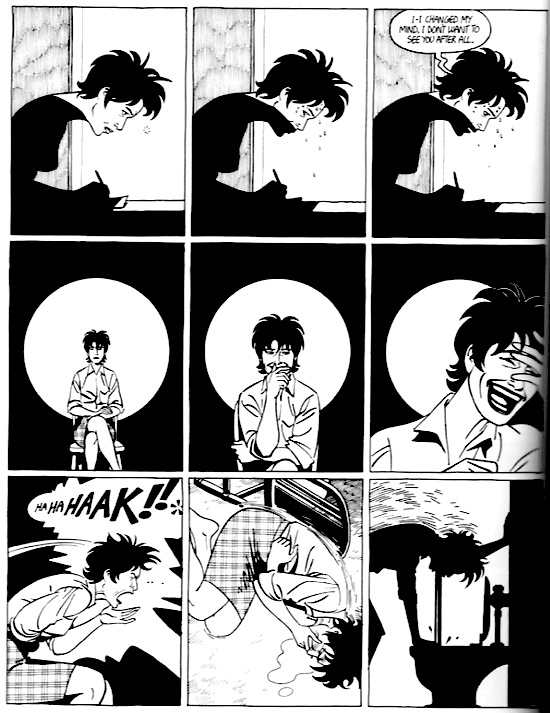

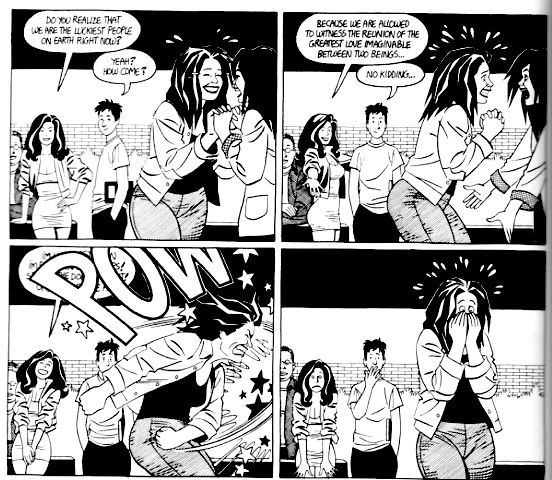

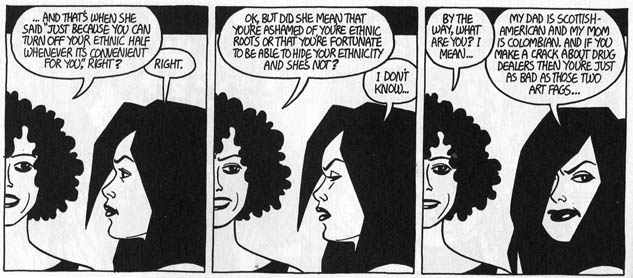

In addition to calling upon memories across years, even decades, of “Locas,” Jaime also often treats the function of memory (as well as fantasy, a topic that demands its own attention within Love and Rockets) at the level of the page or sequence, and often as the operative dynamic between juxtaposed panels. As others have demonstrated, the Hernandez brothers are masters of transitions, though not in the way typically praised in mainstream comics. As Charles Hatfield has noted, despite their preference for standard “grid” layouts, both Gilbert and Jaime Hernandez “nonetheless take a drastic approach to narrative elision …” relying on the technique Joseph Witek calls “uncued closure,” which (as Hatfield says) “pits image, image-series, and page surface against each other.” Shifts between panels are often surprising and jolting, more in the tradition of Eisenstein’s theories of montage, in which he defined the dialectical relationship between shots as “collision,” rather than the smoother “linkage” favored by his equally brilliant contemporary Pudovkin, which might define the transitional goals of most comics creators. (Early comics suggest the form experienced some anxiety in this regard, as in Winsor McCay’s numbering of his panels, or in the arrows that guide readers in the dynamic fight sequences in Jack Kirby’s early Captain America pages, devices that seem to indicate some concern about readers’ abilities to move forward correctly.) Jaime typically avoids the nondiegetic clarifications that hold the hands of readers moving through more conventional comics: the small boxes that carry us across time or space with a helpful “meanwhile …,” “later that day …,” or “At a secret hideout on the other side of the world …” as well as the more recent technique shared by mainstream “widescreen” comics and contemporary films that provide “on-screen” titles identifying a location and perhaps date and time to guide readers. In Love and Rockets (which is hardly unique in this regard) the leap across panels can be uncertain and disorienting rather than obvious and “invisible.”

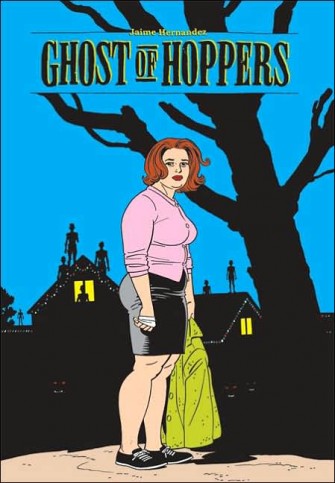

In their exploration of memory at all levels, the sequence of stories centered around Maggie and Hopey in Volume II of Love and Rockets is exemplary. (This material was first collected in the volumes Ghost of Hoppers and The Education of Hopey Glass, which were combined to make up the recent “collected works” volume Esperanza; this material is also all found in the larger volume Locas II). The “ghost” referred to in the title Ghost of Hoppers is explicitly Maggie, experiencing the genuine nostalgia of return, in the original Greek sense of the pain — rather than fuzzy warmth the bastardized use of the term connotes — one experiences upon returning to a “home” that will never again exist as one once knew it. (Maggie experiences nostalgia the same way Ulysses does: it hurts.) But she might be just as easily described as haunted rather than a haunt herself: she’s haunted by memories of the past that return in (appropriately for a comic) strikingly visible and sometimes fantastic forms (a demonic dog and dog-footed child). In a larger sense, the second volume of Love and Rockets is haunted by memories of the (younger, somewhat more carefree) first volume, and so the reader of this series – returning to familiar yet changed characters and settings after the gap the Hernandez brothers imposed through a hiatus of about five years – is also called upon to recall that past which constantly burdens the forward progress of these characters and this narrative. (Whether they wanted to or not, it’s worth recalling that the Hernandez brothers “returned” to the familiar narratives of Love and Rockets because of fairly consistent reader demand. Despite work on other projects, they seem fated to never escape the persistent drag of their most successful creations.)

In order to represent the tricks of memory (or, again, the transition from objective reality to fantasy or dream, a comics tradition that goes back at least to McCay) Jaime may present panels in a sequence that requires the reader to briefly back up, understanding transitions not just by forward movement but through brief retrospection, a step back in order to move forward with an understanding of how the ground has shifted. The propulsive forward motion that seems to define the consumption of comics, panel by accumulative panel, is in this case staggered by a movement that shuttles between projective and retrospective understanding. (For an otherwise strained cinematic comparison, consider the famous transitions in the films of Yasujiro Ozu, which are often only clear once they are over.) In a number of instances, Maggie wanders through panels which otherwise represent her past, like a dreamer; more complexly, the shift from present to past is made via panels in which the adult Maggie looks out a window at herself as a child, with each version drawn in a distinctive style: the adult Maggie is more realistic, the child Maggie is more cartoonish. (The sequence in fact dramatizes the moment when little Perla accepts being called Maggie for her future.) Emphasizing their complex status as a couple and pair across the full history of “Locas,” Hopey will view herself as a child in the same way in another sequence. Such sequences are briefly disorienting, and only fully comprehensible through a reading that steps back for confirmation before securely moving forward: in one panel Maggie is looking at some kids; although the stylistic shift should cue us, only the identification of one of the children as “Perla” in the next panel clarifies that a temporal shift has taken place, and thus we re-read the previous panel in light of what follows it. We come out of this detour into the past in the same way, via a panel of Maggie-in-the-present again looking out the window (but now from the interior rather than the earlier exterior) at Maggie-in-the-past. In a few more panels, Maggie will see herself and Letty pass by: in the cinema, these would be misleading eyeline matches, organized to imply spatial contiguity and temporal simultaneity, but which in fact articulate impossible spatial and temporal coordinates, only available in memory, dream, or delusion.

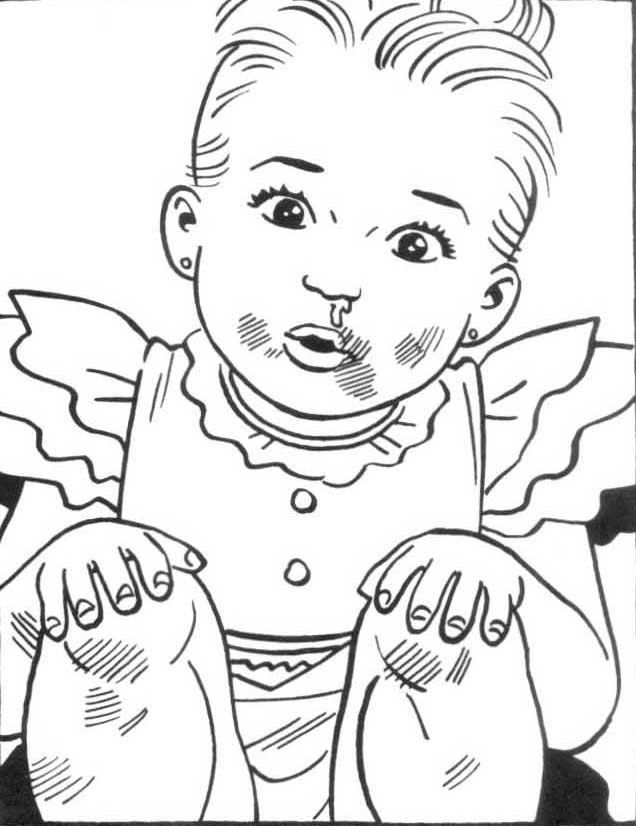

Jaime is celebrated for his representations of children, in a style that derives (as he acknowledges) from the kid-comic traditions of Dennis the Menace, Little Archie, and (to a lesser extent) Peanuts. But it’s not often noted that he does not always draw children in this way: these “cartoonish” kids are often children as they appear in memory as opposed to representations of his characters in the historical past, who retain more realistic qualities. Jaime’s characters seem to remember their own childhoods in the visual idiom of early kids’ comics. In other instances, children are drawn in a style that matches depictions of adults, as in the devastating flashbacks of “Browntown” and “The Love Bunglers” in his most recent work. But when his characters recall themselves or others as children, such memories seems to signal the artist’s recourse to his own memory of how children appeared in comics when he was a kid. (This is loosely related to the technique, perhaps first employed in Alan Moore’s run on Supreme, of having the memories and/or history of that Superman knock-off drawn in the style of Silver Age DC comics, in marked contrast to the generic style of contemporary superhero comics otherwise employed by Moore’s artists.)

Although a number of critics have questioned or criticized the notion of “collective memory,” which might be another term for what we attempt to define as “history” (all too often in its most “official,” hegemonic forms), Jaime Hernandez’s work across the past three decades relies – for at least some of his readers – on a relay between the memories of his characters, his own narrative sensibility, and the recall of his audience. (Fantagraphics of course plays a considerable role by keeping everything in print: in terms of the preservation of memory, we might call the many collected volumes of Love and Rockets an archive.) Reading “Locas” is, in effect, remembering “Locas.” This is not to say that Jaime’s narrative has no future (a promise his last work, again, takes to a surprising new level), but that it seems bound to remain haunted by the persistent past.

______________

The index to the Locas Roundtable is here.