____

This is part of the Gay Utopia project, originally published in 2007 . A map of the Gay Utopia is here.

Category Archives: Blog

Romance as Criticism, Criticism as Romance

Many romances are meta, but surely few can be as meta on their meta as Kathleen Gilles Seidel’s iteratively titled Again. The novel’s heroine, Jenny Cotton, is the chief writer on a soap opera, My Lady’s Chamber, which is set in the Regency period. The novel, then, is both a historical and a contemporary, with the two constantly commenting on each other, as Jenny distributes the characteristics of her unsatisfying maybe-soon ex Brian and her possibly potential suitor Alec to various period figments of her imagination. Jenny has been with Brian since they both were children, but she only discovers that he’s a selfish git incapable of generosity or caring when Alec, playing the evil duke Lydgate (where’d that name come from?) picks up on one of Brian’s characteristic mannerisms. So Jenny reads Brian by reading Alec, or more accurately, Jenny reads Jenny by reading Alec reading Jenny reading Brian — which is to say, Jenny figures out that she has modeled Lydgate on Brian when Alec playing Lydgate picks up on Brian’s mannerisms to portray the character. Past, present, self and other, and, most emphatically, reader and read are shuffled about as in a shell game; the heart (whose heart? everyone’s heart?) is revealed simultaneously through reading and being read — the protagonist as text, reader, and critic.

Many romances are meta, but surely few can be as meta on their meta as Kathleen Gilles Seidel’s iteratively titled Again. The novel’s heroine, Jenny Cotton, is the chief writer on a soap opera, My Lady’s Chamber, which is set in the Regency period. The novel, then, is both a historical and a contemporary, with the two constantly commenting on each other, as Jenny distributes the characteristics of her unsatisfying maybe-soon ex Brian and her possibly potential suitor Alec to various period figments of her imagination. Jenny has been with Brian since they both were children, but she only discovers that he’s a selfish git incapable of generosity or caring when Alec, playing the evil duke Lydgate (where’d that name come from?) picks up on one of Brian’s characteristic mannerisms. So Jenny reads Brian by reading Alec, or more accurately, Jenny reads Jenny by reading Alec reading Jenny reading Brian — which is to say, Jenny figures out that she has modeled Lydgate on Brian when Alec playing Lydgate picks up on Brian’s mannerisms to portray the character. Past, present, self and other, and, most emphatically, reader and read are shuffled about as in a shell game; the heart (whose heart? everyone’s heart?) is revealed simultaneously through reading and being read — the protagonist as text, reader, and critic.

Not just any critic, either. Like Jennifer Crusie’s Welcome to Temptation, Seidel seems to deliberately reference and engage with the major early feminist critic of romance, Janice Radway (and probably also with Tania Modleski, whose work drew explicit parallels between romance and soap opera.) Radway argued, following Nancy Chodorow, that the romance genre was a fantasy of reconcilement with the mother. Romances, she said, presented brutal men who were eventually melted by love into unexpectedly maternal softies, providing women with the consolatory dream of a caring patriarchy of love and empowerment, and so enabling them to tolerate their inadequate marriages and lives.

Radway’s thesis is quite unpopular with many current romance readers, if my experience mentioning her name on social media is any guide, and Seidel is undoubtedly being arch when she provides an almost parodically perfect Radway narrative of man-as-mother-substitute. Jenny’s own mother died when she was a year old, and as a result she feels that she never learned how to be a woman, and never had anyone to take care of her. For his part, Alec is an obsessive care-taker; in just about his first meeting with Jenny, he discovers she’s having a miscarriage and bustles her off to the hospital, literally sweeping her off her feet to carry her at one point. She needs a mother; he’s a mother. The Radway formula, illustrated.

Except it doesn’t quite work that way. While Jenny wants a mother, she rather hates being taken care of. For his part, Alec over the course of the novel runs through his emotional reserves; he falls in love with Jenny, but the strain of constantly trying to take care of everyone (as he once took care of his terminally ill sister) eventually renders him inert. The storyline resolves not through Jenny discovering a mother in Alec, but rather through her realization that she, herself is her mother. She always thought that her mother would have been good at the “girly stuff” — dressing up, being frilly and elegant and glamorous. But after breaking up with Brian the jerk, Jenny realizes that her mother (whose chief love was driving around from pool hall to pool hall with Jenny’s pool shark dad) was just as much of a tomboy as her daughter. Jenny doesn’t need a guy to be a mother because she was always already her mother herself. Instead, it’s the mothering guy who needs to be taken care of. Or as Alec puts it (after some coaching from Jenny, feeding him his lines as is her wont) “I need you to explain to me how I need you.”

Except it doesn’t quite work that way. While Jenny wants a mother, she rather hates being taken care of. For his part, Alec over the course of the novel runs through his emotional reserves; he falls in love with Jenny, but the strain of constantly trying to take care of everyone (as he once took care of his terminally ill sister) eventually renders him inert. The storyline resolves not through Jenny discovering a mother in Alec, but rather through her realization that she, herself is her mother. She always thought that her mother would have been good at the “girly stuff” — dressing up, being frilly and elegant and glamorous. But after breaking up with Brian the jerk, Jenny realizes that her mother (whose chief love was driving around from pool hall to pool hall with Jenny’s pool shark dad) was just as much of a tomboy as her daughter. Jenny doesn’t need a guy to be a mother because she was always already her mother herself. Instead, it’s the mothering guy who needs to be taken care of. Or as Alec puts it (after some coaching from Jenny, feeding him his lines as is her wont) “I need you to explain to me how I need you.”

In Radway’s formulation, romance is a trans-gendered pleasure — a fantasy of women loving the women within men. Seidel’s reworking doesn’t so much put every gender back in its place as it infinitely iterates (“Again”) the cross-gender swapping. Jenny, the tomboy, becomes the caring man as mother; Alec, caring man as mother, becomes the woman swept away and cared for. “Someone else was making everything absolutely perfect,” he thinks at the end. “There was something to be said for a woman with imagination.” The “woman” there is supposed to refer to Jenny — but given the fact that imagination for Radway is figured specifically as the transgendering of the love object, it must also refer to Alec, who, transgendered himself, is the one experiencing the characteristically Radwayian romance of motherly protection from a strong patriarchal figure (she is, after all, his boss.)

This scrambling of gendered positions is in part a critique of Radway’s critique of romance. Romance, Seidel says, is not (or doesn’t have to be) about fooling oneself into thinking that the patriarchy is your mother; it can be about insisting that women can take care of themselves, both personally and professionally. But if that’s critique, it also seems like conversation — and, perhaps, assurance. Psychoanalysis is always, after all (as that prime fetishist Freud demonstrates) self-psychoanalysis, which means that Radway’s supposed excavation of the romance readers psyche might perhaps better be read as a projection of Radway’s own particular neuroses.

And that is in fact how Seidel reads it. In a footnote to her discussion of Radway in the collection Dangerous Men & Adventurous Women, from 1992 (just two years before Again) Seidel says this:

Janice Radway, in her 1987 introduction to the British edition of Reading the Romance…acknowledges the “residual elitism which assumes that feminist intellectuals alone know what is best for all women.” In a graceful, moving statement, she suggests that such scholars should offer romance readers and writers “our support rather than our criticism or direction.” She follows this generous-hearted position with the most discouraging words I encountered in all the reading I did for this essay as she dismisses the possibility: “Our segregation by class, occupation, and race [race?] works against us.” We are still Other to her; she does not believe either party can speak to the other. I find this inexpressibly sad.

Seidel, then, reads in Radway a tragic fissure, a split between women and women — which is precisely the tragic fissure that Radway reads into romance readers and writers like Seidel. It is not romance readers, but Radway, who is bifurcated; it is not romance readers, but Radway who needs to be reconciled with the mother — or, in Seidel’s version, to realize that she is already reconciled with the mother, and that the romance is already hers.

Again, then, can be read, not as (or not just as) a refutation of Radway, but as a love letter to her. And part of what that love letter says is that Radways’ book is itself a love letter — that “Reading the Romance” can itself be read as a romance.

That romance isn’t utterly untroubled. Seidel has a lot of fun in the novel with a rival soap opera, Aspen!! written by the (significantly) male writer Paul Tomlin, a man who “didn’t know anything about soaps”, and who seems to have contempt for the form and for the audience. The satire of those who hope to save romance and romance readers for better, higher things certainly implicate Radway, tweaking her condescension and her separation of herself from her subject — the way she wants to write in romance without actually writing romance.

But the very act of criticizing the critic puts one, inevitably, in the position of critic. The original name of Aspen!! was Aspen Starring Alec Cameron; the Othering Othered is also the loved one — albeit a loved one who needs to be taught to love. And that teaching is criticism, too. “I suppose we’re to conclude from that that my best chance of being an acceptable human being is to be married to you?” Alec says, after Jenny has explained their relationship to him through a critical reading of the ongoing plot of In My Lady’s Chamber. Criticism speaks romance and romance speaks criticism. And when the genres are so nested in each other, how can you tell who is outside or who is inside, or who is saving whom?

How Does What’s In Print Affect Comics Studies?

I have been thinking about access in comics studies lately, about the way the availability of resources can be used to steer critical interests in the field. Publishing houses and archivists, collectors and copyright holders, even cultural guardians – there are a lot of people and institutions involved in making decisions about which titles to seek out, preserve, and keep in print. Of course, anyone who works among the ephemera of popular culture faces similar challenges, but my question focuses on the implications for comics scholarship: How does access to materials shape the choices you make about the comics you study, teach, or review?

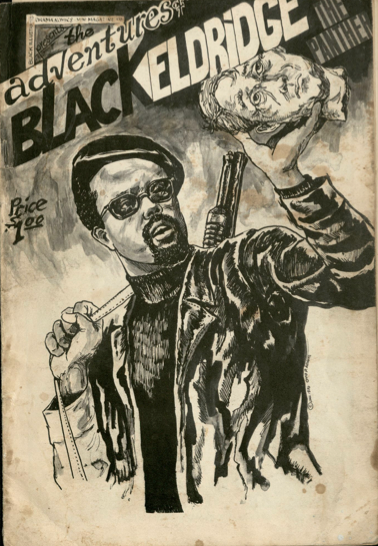

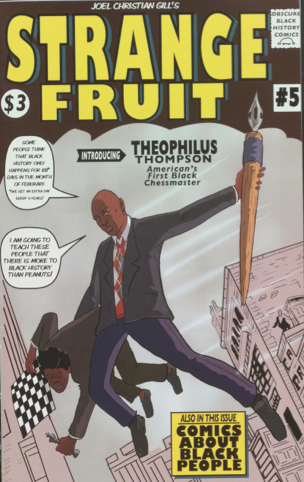

Last week, I visited the comic book archives at the Library of Congress in DC and at Virginia Commonwealth University’s James Branch Cabell Library in Richmond. Although I arrived with a list of rare comics and fanzines that I wanted to read, the best part of spending time in archives was getting the chance to talk with the reference librarians who maintain the collections and know where to look for hidden gems. Thanks to Cindy Jackson at VCU, I got to turn the pages of The Adventures of Black Eldridge: The Panther, a newly-acquired underground comic produced by Ovid P. Adams in 1970. Megan Halsband at the Library of Congress introduced me to Joel Christian Gill’s recent series of Strange Fruit Comics that uses satire and comics culture to dramatize obscure black historical figures (along with great bonus features like “Lil’ Nino Brown in Slumland”).

You may have to travel to Richmond to see Black Eldridge wield his machete against the villains of white supremacy, but Gill blogs about his work online and his Strange Fruit Comics are being collected in a new edition out this June. And it’s a good thing too, because quite a few of the titles I regularly teach in my class on race and comics are now sadly out of print and I don’t know how long I can keep asking students to hunt down used copies.

Questions of access must also take into account the way comics as a form continues to be disparaged ideologically by those in positions of power. Complaints that the College of Charleston forced last year’s incoming students to endure lesbian “pornography” in Alison Bechdel’s graphic novel, Fun Home, also prompted South Carolina State Representative Tommy Stringer to tweet: “Is the instructional ability of CofC teachers so low that they have to use comic books to teach freshman?” The material consequences of this kind of thinking are extremely serious; the state ultimately voted to slash the first-year reading program’s dollars from the college’s budget.

One wonders if Rep. Stringer would level the same accusations of teacher incompetency if the College of Charleston had selected March: Book One for their freshmen reading selection, as Michigan State and Marquette University are doing this fall. U.S. Congressman John Lewis has been signing copies of his graphic novel memoir to standing-room only crowds across the country. In interviews, Lewis along with his co-writer Andrew Aydin and artist Nate Powell have often praised the ability of comics to inspire social change and reviews celebrate the novel’s success as a teaching tool. Furthermore, the 1958 comic book, Martin Luther King and The Montgomery Story, is available for purchase again due, in part, to a reference in Lewis’s graphic novel and the publicity surrounding distribution of the comic book’s translated Arabic edition during the Arab Spring in 2011. I suspect that high schools and colleges will keep these comics in print for a long time.

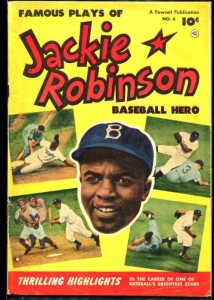

The research that I’m doing now on EC Comics greatly benefits from the initiatives of fans that have worked hard to keep reprints in circulation. The same can’t be said, though, for comics like Fawcett’s Jackie Robinson series, also from the 1950s. Last week, I had the chance to read three issues (three!) from the series, along with one about Joe Louis and Willie Mays, all incredibly fragile and rare. I’m eager to write about these comics, to try to make some kind of meaningful connections with other titles produced during this period. (Who knew that Robinson apprehended cat burglars in his spare time?) But now I’m realizing how important it is that we also work with publishers to make these comics more readily available. If readers can’t get better access to titles like Jackie Robinson or The Adventures of Black Eldridge, how can they become a part of larger critical conversations in comics studies?

Prophet, The Incal, and Suggestion in Science Fiction

In the science fiction short story The Island by Peter Watts, a group of human engineers sets out on a mission to build warp gates across the universe. As they travel from one build location to another, they move at such at such high speeds that a few years for the builders is the equivalent of billions of years on earth. Every time they complete another portal, they get a brief look at the offspring of humans that is living at the other end of the gate, where earth once was. “I’ve seen these portals give birth to gods and demons and things we can’t begin to comprehend, things I can’t believe were ever human.”

Over the past few years, dark, intricately-woven science fiction universes have multiplied at Image and other publishers, and many of them tap into the feeling of Watts’s engineers, the wonder of seeing something we are unable to understand. These stories walk a fine line between suggestion and fulfillment. They must depict a universe so different from our own that it stretches our minds to think about it, and then they have to explain it. We aren’t content merely to gaze upon a bizarre creation, we also want to understand it. This is the core challenge that a science fiction world must answer: How do you depict the unimaginable?

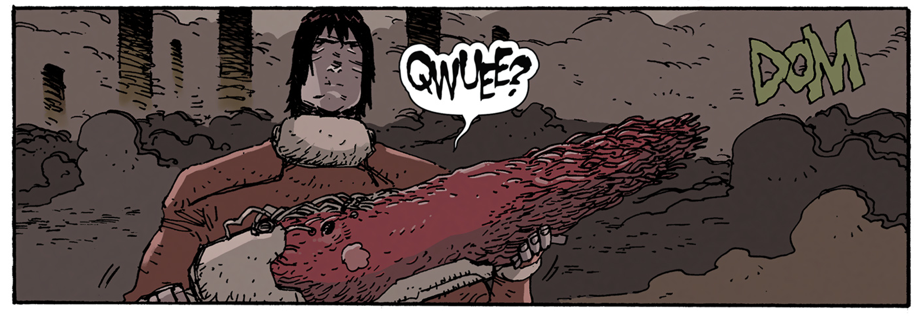

One title that stands out is the Brandon Graham reboot of Prophet. Graham has assembled a stunning team of artists to illustrate and write the story with him, which is loosely based on a Rob Liefeld character. The story takes place 10,000 years in the future, and it’s pages are rich with imagined history, from the biological technology to the debris of forgotten wars. The setting and story evoke the nostalgic fascination that European and American painters felt for the ruins of the Greco-Roman empire.

Prophet

I am consistently delighted by how bizarre and alien the world of Prophet feels. The hands-off story telling allows me to fill in the gaps of the worlds that Graham describes in a way that feels organically collaborative. It reminds me of another science fiction comic which taps into the infinite, The Incal by Alejandro Jodorowsky and Moebius.

Jodorowsky is best known as the director of the surrealist film the Holy Mountain, and for the ambition of his plans for a film adaptation of Dune. After assembling a team of creators that included Orson Welles, Dali, Moebius, and H. R. Giger, the project went over budget in pre-production and was canceled, it’s components later harvested to make Alien, Blade Runner, David Lynch’s Dune, and others. Jodorowsky’s Dune was too revolutionary to be realized, and that is exactly why the comics that he went on to create are so fascinating.

In comics, Jodorowsky found a medium where he could work without constraints. He said in an interview, “If you want 10,000 cosmic spaceships, it doesn’t cost more money than drawing a horse.”

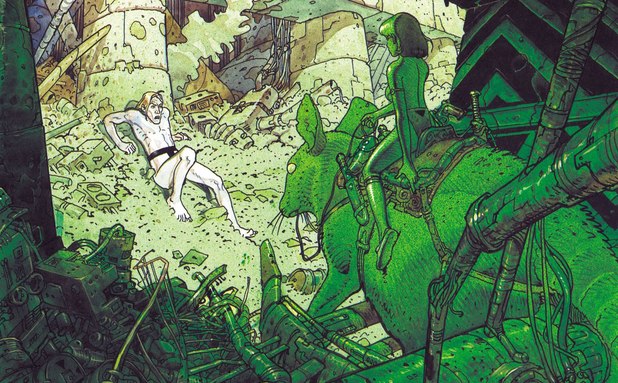

The Incal, published from 1981 to 1989, is the story of a foolish, selfish white man named John DiFool who is pulled into a journey across space by the metaphysical spirit known as the Incal. DiFool is dragged throughout the adventure not because he is special, but because his genetic code resonates with the Incal. He is a bumbling participant in the cosmic and spiritual war that unfolds.

Both Prophet and The Incal succeed in creating a world that feels at once inconceivable and familiar. To do so, Jodowrosky and Graham (Note: from here on I’m going to refer to the Jodorowsky and Moebius collaboration and the Graham and team collaboration as Jodorowsky and Graham respectively) both use dialogue and narration to suggest a much larger universe than they are ready to spell out on the page. In the Incal, it does not matter that we know little about the Technopriests, the Emperoress, or even the Incal. We understand the roll they play in the story, and can create our own mythology around them. This technique is even more common in Prophet, with dozens of technologies, wars, and worlds (Foam Music, Ambulavit Pod, Lux Glacies Caverns) that appear only for a single line.

This collaborative world-building technique is not limited to throwaway details, but is also used to drive the plot forward. Prophet waits until the end of issue six to introduce the primary conflict of the series, the battle between the earth empire and Old Man Prophet, a clone who has rebelled. There are several short stories in Prophet that don’t openly announce how they fit into the comic’s overall plot, and the reader wanders through the pages with the characters, trying to piece together what has happened. Even the first image of an earth empire ruler, though bizarre, cannot be read in a moral framework.

Ambiguous depiction of the earth empire in Prophet.

Once the narrative engines get running, it’s clear that the story exists in a binary good versus evil universe, and not even a particularly original one (empire=evil, white-guy-who-fell-in-love-with-a-native-woman=good). Even the character design seems to become more explicit. Where the first images of the earth empire Mothers just look strange, later images portray them as monsters. Once the incremental exposition had filled in enough gaps that I could see the larger arc of the plot, I began to feel nostalgic for the complex, morally ambiguous universe I had been imagining around the characters.

This is one of the pitfalls of using suggestion to flesh out the world. The Wachowskis have spoken in interviews about the tremendous challenge of realizing and expanding the science fiction universe in Reloaded and Revolutions that they had alluded to in the Matrix. Another manifestation of the gap between expectation and realization occurs when writers who have established a hard science universe introduce elements of spirituality and mysticism (for example, the recent Battlestar Galactica series).

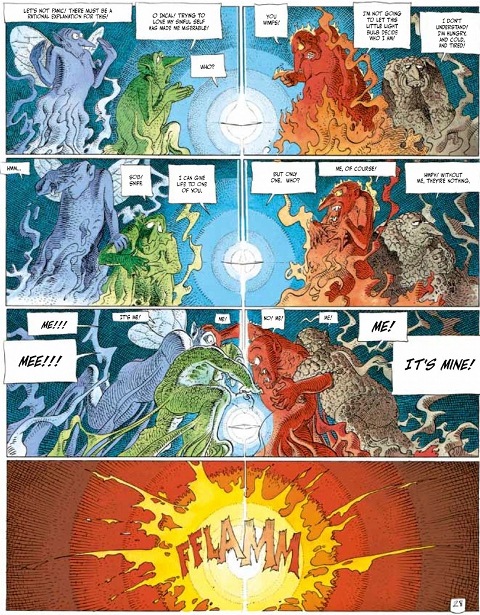

Jodorowsky’s Incal avoids this trap from two different directions. First, it is upfront with the metaphysical, psychedelic weirdness of its world. On page 32, the Incal splits John into four competing gnomelike characters that represent aspects of his personality. It’s a bizarre and awkward turn in the story, but it does an excellent job of signaling the rules of the universe to the reader (no rules). Later, when the battle between light and dark takes center stage, it feels like an extension of the book’s themes instead of a reversal.

The four spirits of John DiFool in The Incal.

The second way that The Incal exceeds expectations is by beginning with a relatively straightforward swash-buckling adventure, and then expanding and interrogating parts of the universe until it is much larger. The Incal feels like a small story is growing, while the Prophet feels like a large potential is shrinking.

In later issues of Prophet, Graham pivots the narrative arc by focusing on the a new threat and introducing more characters pulled from the original Liefield Prophet universe. It feels rushed and I didn’t feel any pressing need for the book to be truer to the Liefeld universe, but I’m happy to see the story move in any direction that is not a steady march towards a boring war. One of The Incal’s greatest accomplishments is that even though the story changes direction repeatedly (in the most bizarre turn, the characters must convince all living creatures in the galaxy to fall asleep and enter the Theta-dream together), each iteration feels like a movement closer to story’s core themes. If Graham can make similar course adjustments on Prophet, he will have something truly special.

Art vs. Art: Zen Pencils and the Critical Imagination

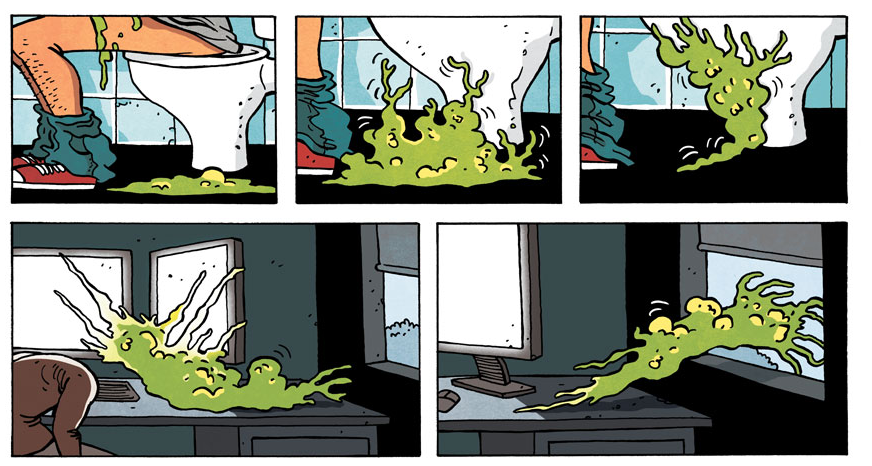

Trying to figure out the exact point of Zen Pencils has not been easy. Created and written by Australia-based cartoonist Gavin Aung Than since 2012, it is at least usually a series of comics about inspirational quotes made by famous people, a sort of Chicken Soup for the Cartoonist’s Soul. With its feel good premise and emphasis on inner creativity, self-realization and the transformative power of a single out-of-context quote, it isn’t surprising that the comic series has been since its inception a hit on Facebook walls and Pinterest boards alike. Whether or not you recognize the author, if you’ve seen a comic floating around about a quote by Carl Sagan, Helen Keller, or Theodore Roosevelt, chances are you’ve seen some of Aung Than’s work. Though not all focused on unrelenting positivity, the vast majority of Zen Pencils comics are small and quickly gratifying fell-goodisms, nuggets of good vibes that find their ideal germinating ground in the digital networks of chain emails your uncle likes to send out. Yet at the same time, Zen Pencils has long had an underlying current of negative, vitriolic vein of thought running through it, expressed in angry comics on teaching, the terrors of post-graduation life, and the impact of technology on society, among others. These comics received a certain degree of notoriety for this, and, as this is the internet, a certain degree of trolling directed at Zen Pencils in general and Aung Than in particular. But it is not these initial comics that the crux of Zen Pencils’ notoriety rests on, but rather the way Aung Than responded to his critics; by creating a massive, four part comic about the evils of his interlocutors. It’s an ignominious, textbook example of how one should not respond to criticism.

The comics begin with a group of internet critics and naysayers, apparently quite literally full of shit, bursting into piles of green sludge randomly and violently. As more and more cardboard cutout cynics meet their fate this way, the green sludge begins to take form, transforming into a massive slime monster aptly titled (and with a hashtag) #hate. To counter the threat of #hate, which threatens to engulf all creativity and art in the world, an anachronistic group of artists led by one “H. Miyazaki” (copyright issues and all) gather together and, with veritably Captain Planet like gumption, form a giant mecha robot called A.R.T., emblazoned with an inspirational quote by Theodore Roosevelt, and blast off to fight the evil #hate in a climactic showdown. When they finally succeed in the comics’ thrilling conclusion, they take the entrails of their slain adversary, fly to the moon, and write the word ART on its surface as a message (and perhaps a warning) to all those who may question and criticize art.

Be afraid, my fellow HU critics.

There is so much going in this bizarre four part comic, written by a man best known for writing feel-goodisms about Albert Einstein and Helen Keller, it’s difficult to know where to begin. For long-time naysayers and critics of Zen Pencils, this vociferously anti-criticism criticism is going to do little but validate their objections, that Aung Than’s work is little more than moralizing, didactic tripe that doesn’t see the world with nuance. And in doing so, of course, they will only reinforce Aung Than’s position that critics are hacks at best and slime beings at worst. So where is there to go from here? It seems all too easy to dismiss the Art vs. Hate comics as angry, senseless diatribes, long winded rants in the vein of a public meltdown, but there’s a clear form and directionality to these comics that your average twitter breakdown lacks. Aung Than has planned out these comics thoroughly, and released them successively, each within a few weeks of each other. Several weeks to a month seems a long time to hold onto the white hot rage the comics seem to project, so what is their purpose? Aung Than is clearly making a statement, however confused and angry, and this in itself seems worth at least trying to unpack. What he ends up expressing is not a rant so much as a Manichean prophecy, a declaration that we live in a world of light and dark, art and criticism, #hate and #create. And we – all of us, from immediate readers to anyone with a stake in the exploration of art itself – must take a side. Will we stand with the artists, and try to create? Or will we be swept away as critics, like so many little slime monsters?

The glaring weakness in Aung Than’s dichotomy is the weakness of most dichotomies – that the binary they are predicated upon does not really exist. In writing this article, I am at least ostensibly in the position of critic, but I do not think of myself solely as such, and dedicate much of my time to my own creative endeavors. Does this make me a critic, or an artist? Am I made of slime and hate, or goodness and creativity? In truth, I and most people are a holistic mix of both. Criticism is not inimical to art; it is the molecular reaction, the most basic process, through which art of any sort is created. Art doesn’t emerge from a vacuum; it is created in response to the world, indeed as criticism towards it, and art evolves as an active process of criticisms and reassessment across decades and centuries. The Realists would not have emerged were they not critics of the Romantics; Postmodernism would never have occurred were it not for the faults present in Modernism. The moment we strip art of its critical dimension, we strip it of its ability to grow, to change, and to affect us. Art, if it is to serve a purpose, cannot simply stop being critical or subversive when we deem it so; it cannot be made for its own sake. And if you will forgive me for trying to answer the forbidden ‘what is art’ question, I would say that art exists to inform, to reflect, and to critique, and the moment it ceases in this function it is no longer art. It is something else entirely.

I hope #Hate isn’t #trending.

Is this what Aung Than wants? To strip art of its critical component and make it a dead and static thing to be hung up on a wall and endlessly gestured to? I do not think so. Zen Pencils is based on the words of wisdom spoken by some of the most notable figures in our world, and many of those figures quoted are indeed artists. Imagine a world where artists did not exist to say inspirational things! What would Zen Pencils, Hallmark, and the chain email enthusiasts of the world do?! The horror! But in all truth, in evaluating the Art vs. Hate comics, my suggestion would be for Aung Than to think back to one specific character; H(ayao) Miyazaki, his self-described biggest idol and influence. What is it about Miyazaki’s work that he appreciates the most? What does he try to emulate, and what makes it worthwhile to him? Criticism is not merely an act of negation; it is as much choosing what to keep in creative endeavors as it is figuring out what to leave behind, and what to oppose.

I do not say any of this to condescend to Aung Than or his work, for when it comes to mindlessly negative internet trolls and their detrimental impact on discourse and the creation of art, we are in total agreement. The nastiness directed towards Zen Pencils does not constitute good criticism, but the comics as a whole could stand to realize that there is more to the process of creating than empty eulogies. In raising art to a pedestal-beyond-pedestals, Zen Pencils does not enshrine art, but merely the idea of art, an empty rhetorical figure used metonymically to refer vaguely and uncritically to everything good and pure in the world. This emptying out of art, so to speak, is not a new phenomenon; defending art for art’s sake, as if art exists independent of the world from which it arises and must be bulwarked against that very world, is a common and noxious idea that gains ground whenever one speaks of art as a goal in and of itself. It is easy to appreciate art, to worship the very idea of it and identify it as the sentinel against which all the evils of the world are kept at bay, but this is tantamount to a betrayal of art itself. Art does not preserve the world, nor does it transcend it; art creates the world, and to criticize is to define and create art itself. We make art not to transcend the world, but to critique it, and make it a better place. And when we can fully recognize and appreciate this, then maybe Aung Than’s dream will be realized, and art will truly triumph over #hate it all its forms.

I’m not the first to point it out, but there’s something truly unfortunate about the idea that “H” Miyazaki would find much wisdom in the words of noted white supremacist and American imperialist cheerleader Theodore Roosevelt.

XX-Men: The Failures of Brian Wood’s All-Woman X-Team

A very slightly different version of this post first appeared at The Middle Spaces.

At the end of last year, Orion Martin wrote a piece for The Hooded Utilitarian entitled, “What If the X-Men Were Black?” that argues that the metaphor of Civil Rights issues as persecuted mutants fails, or that at the very least the elasticity of the mutant metaphor to cover race, gender, sexuality, ethnicity means that it’s susceptible to appropriation and undermines any ability to productively comment on those social issues. Impressed by this essay, I thought it would be interesting to look again at the first arc of Brian Wood’s recent X-Men series, which features a much hyped team of all women and see what the result might be of a mutant superhero group in which the persecution metaphor might be peeled away due to the fact that all the team members are women, in favor of a more direct reflection on issues facing women, both as members of the X-team, but also as characters who ostensibly directly represent a real-world (albeit diverse and far from monolithic) political identity.

Marvel’s X-Men has a decent history of including women in its super-teams, sometimes even in the role of leader. You have to ignore the original X-Men where Marvel Girl (aka Jean Grey) was the only woman, but later, Jean would be joined by Storm, and then Kitty Pryde, Rogue, Rachel Summers, Psylocke, Dazzler, Jubilee, and so on… The New Mutants had Wolfsbane, Karma, Dani Moonstar, Magma. Various forms of X-Factor and X-Force all had women team members. In fact, take Dazzler and Jean Grey out of that first list and you have the core of Wood’s X-Women team, but that record of including women is still only good in relation to the rest of superhero comics. There are still a ton of more men in the X-Men than women, and aside from Storm and Jubilee, the most popular X-Women have all been white…

Marvel’s X-Men has a decent history of including women in its super-teams, sometimes even in the role of leader. You have to ignore the original X-Men where Marvel Girl (aka Jean Grey) was the only woman, but later, Jean would be joined by Storm, and then Kitty Pryde, Rogue, Rachel Summers, Psylocke, Dazzler, Jubilee, and so on… The New Mutants had Wolfsbane, Karma, Dani Moonstar, Magma. Various forms of X-Factor and X-Force all had women team members. In fact, take Dazzler and Jean Grey out of that first list and you have the core of Wood’s X-Women team, but that record of including women is still only good in relation to the rest of superhero comics. There are still a ton of more men in the X-Men than women, and aside from Storm and Jubilee, the most popular X-Women have all been white…

Racial Aside #1: Psylocke complicates the “white women” aspect of this analysis, but in a way that highlights the deep problems with representations of race and ethnicity in superhero comics. I never gotten over her 1989 transformation from Captain Britain’s big-haired hippie sister into hottie Asian ninja in butt-floss. My complaint about Psylocke is not the race-bending—I am all in favor of black Human Torch or Heimdall and support people’s desire to see an Asian-American Iron Fist—but that her transformation was written into the X-narrative to fulfill the dual fetish of the Asian woman and the exotic ninja killer trope is egregious. She just looks “Asian.” (Well, kind of. There was also some kind of genetic manipulation of the body afterwards or something. Who can keep this stuff straight?) She is literally an Anglo woman whose mind has been put in an Asian woman’s body with no connection to any form of Asian culture or family or community, except in the most facile way that being a “ninja” makes that the case.

Racial Aside #2: Bling! (yes, the exclamation point is part of her name) is a queer African-American student and X-Man in training at the school during this series. However, her crystalline appearance obscures any physical racial markers, and more troubling, her codename and backstory (she is the daughter of a famous rapper couple) become the primary way race is encoded on her.

Racial Aside #2: Bling! (yes, the exclamation point is part of her name) is a queer African-American student and X-Man in training at the school during this series. However, her crystalline appearance obscures any physical racial markers, and more troubling, her codename and backstory (she is the daughter of a famous rapper couple) become the primary way race is encoded on her.

So with that history of better than average—but not good enough—representation of women in X-Men comics and of the team itself being used as a metaphor for disenfranchised groups, it seems fair to judge this X-Women comic with that in mind, and as such, I can say with some confidence, that it fails. Furthermore, if a focus on a new team of women characters was to any degree supposed to attract new readers—more women and/or folks intimidated by the steep learning curve of 50 years of continuity who might see this as a fresh start—it totally fails on that account as well.

I first picked up these issues of Wood’s X-Men not only because I was interested in the representation of women in this comic, but mostly because Rogue, Kitty, Storm and Rachel are sentimental favorites of mine. The height of my collecting X-Men was in the 1980s, and if you don’t count the handful of issues of Grant Morrison’s early New X-Men run (in 2001) that I quickly got rid of, I bought no X-Men comics between 1988 and 2004 when Whedon and Cassaday’s Astonishing X-Men series came out (a series that managed to capture something akin to my memory of the X-Men’s voices from the 1980s—as opposed to the Claremont-reality, which in returning to those early issues I found to not be as good as I remembered), and those 80s comics shaped what I consider my ideal and “most authentic X-Men.” I don’t know from Gambit or Bishop or Jubilee or whoever. That said, despite my fragmentary knowledge regarding 1990s X-Men, I do not count myself as a total neophyte regarding the comics’ characters and major tropes. I’ve managed to glean some info from that era via friends and Wikipedia, and yet in reading this series I found myself struggling to follow what was going on, what was at stake, and why I should care. It’s not hard to imagine that someone totally new to the comics would have been even more lost.

I am not one to complain about the frequent re-booting of numbers in contemporary superhero comics. Personally, I’d prefer for all on-going titles to be series of varying lengths—volumes bound together by time period and or theme, and creative team. I think this would help overcome the crippling burden of continuity, make comic stories easier to organize, and most importantly provide frequent places for new readers to jump on. What is the point of starting a new series with a new number one, if the very first arc is so enmeshed in established continuity that the reader is struggling to catch up with stuff that happened years before in some other version of the series? This is especially the case when the guest star/villain is someone that is basically an obscure character that does not have connection to the iconic stories of X-Men past that might have some reach beyond the die-hard comic fans. Back in the height of my collecting days as a kid, Jim Shooter, Marvel’s editor-in-chief, enforced the philosophy that every comic was potentially someone’s first, and as such writers should write with that in mind. I am not suggesting that we need to go back to the days where a page or two of every issue is dedicated to re-cap, but I do think that, if all that “Marvel NOW!” bullshit is going to really mean anything, any new series needs to make an effort to introduce characters and situations. And I do think it is bullshit, because let’s face it, the urge to completism is what pushes modern comic marketing—own the whole series, own all the variant covers, get the collected trades if you miss something, so that you can understand what happens next. The reason folks complain about the rebooting of numbers, is not so much the numbers themselves, is because despite the editorial lipservice to creating places for new readers to jump on, the re-numbering is about manipulating the collecting culture’s penchant to obsessively pick up first issues despite the harsh lessons of the 1990s comic market collapse. The weak effort of these Marvel NOW! issues and series to actually introduce characters and create something of a fresh start (at least narratively) just reinforces that Marvel is more interested in wringing out every last sale from current readers than finding new ones. It is a classic case of diminishing returns.

There is no effort in this “new” series to establish the characters, but even worse there is no effort to establish or explain why this particular iteration of X-Men…X-Women…exists. It seems like these characters just happen to be the ones who are around when Jubilee calls to say she needs help. If anything, the fact that Jubilee’s problem includes a baby she has recently adopted and is responsible for, suggests that her entre into maternity is what makes this a case for the women of the X-team.

Jubilee is being pursued by John Sublime… Who? Some villain from the X-Men’s past we are told is immensely powerful and dangerous, but if you don’t know who John Sublime is (and I had never heard of him), there is no sense of what he is really capable of, what he has done in the past, and what is at stake in potentially trusting him when he claims to have arrived not to hurt Jubilee, her baby or the X-Men, but to warn them of a new threat. I used Google to look up Sublime’s history and found his backstory to be nauseatingly convoluted and kind of stupid. Stupidity I can handle. These are superhero comics after all, but without any real introduction his presence loses any impact it might have to all save the most informed X-Men fan. I guess he is some kind of hyper-evolved sentient bacteria that can possess people and has psychic powers? Maybe? Actually, even after reading the comic I am not sure what his powers are, because even though he ends up allying with the X-Men, he is never depicted using them.

Jubilee is being pursued by John Sublime… Who? Some villain from the X-Men’s past we are told is immensely powerful and dangerous, but if you don’t know who John Sublime is (and I had never heard of him), there is no sense of what he is really capable of, what he has done in the past, and what is at stake in potentially trusting him when he claims to have arrived not to hurt Jubilee, her baby or the X-Men, but to warn them of a new threat. I used Google to look up Sublime’s history and found his backstory to be nauseatingly convoluted and kind of stupid. Stupidity I can handle. These are superhero comics after all, but without any real introduction his presence loses any impact it might have to all save the most informed X-Men fan. I guess he is some kind of hyper-evolved sentient bacteria that can possess people and has psychic powers? Maybe? Actually, even after reading the comic I am not sure what his powers are, because even though he ends up allying with the X-Men, he is never depicted using them.

The new threat to which Sublime has come to warn the X-Men is his sister, Arkea (I didn’t know bacteria had sibling relationships or identified as a particular genders—like I said stupid—but I am willing to overlook this), except she doesn’t possess people, she possesses machines. That is, except for Jubilee’s baby. She hitches a ride on him, but this is never explained. . I guess it is possible that this baby has a neuro-prosthetic device that allowed Arkea to possess him, since he comes from a hospital where we are told that work is done, but again, it is not explained. In fact, a simple three-issue arc can’t even keep the effects of the possession on the baby (Shogo) straight. Sublime tells Jubilee in issue #3 the reason the baby has been asleep the whole time is because of the possession, but we are shown the baby awake in a panel in issue #1 when he is ostensibly still possessed.

There are several things like this in the narrative—small details that seem to be explaining something, but that only lead to more questions. For example, I guess Rogue can’t fly anymore without absorbing someone else’s power to do so, but still has super-strength and invulnerability? I am sure some X-Men superfan would be able to explain it to me, and a reference to Northstar suggests he was the source of her flight and speed, but since Northstar doesn’t actually appear in the comic, it remains unclear. Again, I can imagine that an X-Men neophyte would really have no idea what that meant despite this being an introductory issue.

Arkea is mostly a direct threat through her possession of Karima Shapandar. Who? This is another character I had never heard of and whose history as an “Omega Sentinel” is deeply convoluted. So, we have a new foe who wants to take over the world who is connected to one former villain turned temporary ally, to another one-time villain turned ally who was in some kind of coma in Beast’s lab until possession by Arkea wakes her up. We are told that Karima the Omega Sentinel is also very dangerous, but since we are simply told all of this in a way that mostly relies on previous knowledge, there is little sense of what is at stake in this story-arc except the most generic idea of Arkea “dominating the world.” Oh, and I guess Karima is their friend, so the X-Men are reluctant to harm her body even though her brain is likely dead.

It is certainly possible that some, if not all of these omissions and poor plotting and characterization are addressed in later plot arcs in Wood’s X-series, but I wouldn’t know because I gave up after the first three issues. There was nothing that made me want to keep up with it, and I am confident that a new reader drawn to a point where in theory they could jump on would likely feel the same way. In fact, I would go as far to argue that this would be especially true of a reader drawn to the ostensible appeal of an all-women X-team, since there is never any effort to make this iteration of the team cohere except as the most cynical sales ploy that is only notable on the meta-level. And if it were to bomb, well then editorial would have an example of an all-women comic that failed to point to when explaining that they just don’t sell—rather than examining their own publishing practice and the flaws in the story-telling (See the recent Fearless Defenders series for another example).

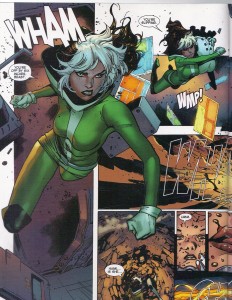

The only saving grace of these three issues is the art by Olivier Copiel and a team of inkers and colorists. In particular, I enjoy the depiction of a scene in issue #2, where Rogue smashes her way into Beast’s lab and seems to break through the panels to evoke her strength and sudden arrival. Generally, speaking the women in these issues are not drawn in the awkward positions meant to display all their physical assets at once, leading to ridiculous contortions, and even Psylocke is drawn with a different uniform from her purple butt-floss ninja classic. I like Rachel Summers Final Fantasy-inspired long red leather coat as well. But there is still some of the typical comics cheesecake, like Akrea/Karima’s semi-supine form when she first awakens or the way Psylocke seems to stick out her butt when she uses her psi-bow, or whatever it’s called. Some of the action sequences are also well-conveyed by the art, though, especially the train derailment sequence in the first issue.

The only saving grace of these three issues is the art by Olivier Copiel and a team of inkers and colorists. In particular, I enjoy the depiction of a scene in issue #2, where Rogue smashes her way into Beast’s lab and seems to break through the panels to evoke her strength and sudden arrival. Generally, speaking the women in these issues are not drawn in the awkward positions meant to display all their physical assets at once, leading to ridiculous contortions, and even Psylocke is drawn with a different uniform from her purple butt-floss ninja classic. I like Rachel Summers Final Fantasy-inspired long red leather coat as well. But there is still some of the typical comics cheesecake, like Akrea/Karima’s semi-supine form when she first awakens or the way Psylocke seems to stick out her butt when she uses her psi-bow, or whatever it’s called. Some of the action sequences are also well-conveyed by the art, though, especially the train derailment sequence in the first issue.

But the art is not enough—at least not by the standard of the first full story-arc (and that seems fair)—to make this series compelling. Perhaps I should not be surprised given Brian Wood’s characterization of the project in an article about the series from USA Today. He says: “I feel like as far as the X-Men go, the women are the X-Men. Cyclops and Wolverine are big names, but taken as a whole, the women kind of rule the franchise.” This could indicate the potential for an interesting take. It brings up the question: why are Cyclops and Wolverine the big names, if the women on the team seem to be the backbone of the franchise? A good series might take up that question more explicitly. Instead, what we get is a series more in line with the second part of his quotation from the news story, “[I]t’s the females that really dominate and are the most interesting and cool to look at. When you have a great artist drawing them, they look so amazing and always have.” Wood gives no indication what makes these women so “interesting,” except perhaps his assertion that they are “cool to look at” and “look so amazing.” When it comes down to it, it is only their appearance as women that makes them interesting in his eyes, not their social position as women in the X-world, or these particular individual characters. They are defined only by their appearance and their sexuality (he makes sure to discuss the potential promiscuity of the characters). Perhaps it shouldn’t come as a surprise given the accusations against Wood by female comics creators, but even if that weren’t the case, I can’t imagine the attitude he displays being all that different from other comics writing dudes, except perhaps that he tries to couch it as liberating to women—as some would say, he is the classic “fake feminist.” Wood seems able to spout the platitudes about how “Most [comics] are written and drawn from a very male point of view, pandering to the largest demographic of readers, and at times with a sexist point of view, with lots of T&A and so on,” but with the inability to see how his own work may fall in line with that tendency as well.

But the art is not enough—at least not by the standard of the first full story-arc (and that seems fair)—to make this series compelling. Perhaps I should not be surprised given Brian Wood’s characterization of the project in an article about the series from USA Today. He says: “I feel like as far as the X-Men go, the women are the X-Men. Cyclops and Wolverine are big names, but taken as a whole, the women kind of rule the franchise.” This could indicate the potential for an interesting take. It brings up the question: why are Cyclops and Wolverine the big names, if the women on the team seem to be the backbone of the franchise? A good series might take up that question more explicitly. Instead, what we get is a series more in line with the second part of his quotation from the news story, “[I]t’s the females that really dominate and are the most interesting and cool to look at. When you have a great artist drawing them, they look so amazing and always have.” Wood gives no indication what makes these women so “interesting,” except perhaps his assertion that they are “cool to look at” and “look so amazing.” When it comes down to it, it is only their appearance as women that makes them interesting in his eyes, not their social position as women in the X-world, or these particular individual characters. They are defined only by their appearance and their sexuality (he makes sure to discuss the potential promiscuity of the characters). Perhaps it shouldn’t come as a surprise given the accusations against Wood by female comics creators, but even if that weren’t the case, I can’t imagine the attitude he displays being all that different from other comics writing dudes, except perhaps that he tries to couch it as liberating to women—as some would say, he is the classic “fake feminist.” Wood seems able to spout the platitudes about how “Most [comics] are written and drawn from a very male point of view, pandering to the largest demographic of readers, and at times with a sexist point of view, with lots of T&A and so on,” but with the inability to see how his own work may fall in line with that tendency as well.

Looking through the list of people who’ve written X-Men comics, I see no women on that list, and while having a woman doing the writing is by no means a guarantee of a good comic, if the women of the series really do dominate it, as Wood would have us believe, then it is beyond time to allow a woman to dominate the series from the writer’s seat for a change. I mean, it’s only been 50 years. Sure, Louise Simonson worked as Claremont’s editor on Uncanny X-Men for four years, and she did get to influence the characters by writing about 60 issues of X-Factor and 30-some issues of The New Mutants, but the flagship title? It has always remained in the hands of men.

10 More Most Underrated Albums Ever

At Salon I have a list of most underrated albums,, but it was cut for space. So here’s what got left off.

Jeri Southern, “You Better Go Now” 1956

Forget icons recognizable by a single name like Billie, Sarah, or Ella; Jeri Southern is little known compared to relatively obscure torch singers like June Christy, Julie London, Peggy Lee and Anita O’Day. But Miles Davis was a fan, and you can hear why on this album. Southern’s voice is pure, bright, and sensual, perfect for the flirtatious vulnerability of songs like “You Better Go Now” and “Remind Me”, or for the tortured lost love pie-in-the-sky hopes of “Something I Dreamed Last Night.” Southern doesn’t waste any tracks on uptempo; the pace throughout is slow, giving her careful phrasing and restrained emotion room to take on weight and depth. “Give me time/I’ll give you love/Give me time/I’ll give you rapture, dear,” she sings, and it’s a promise she keeps.

Bill Harris, “Bill Harris and Friends”, 1957

Jazz trombonist Bill Harris was a longtime sideman for Woody Herman, but as far as I know this record, featuring Ben Webster on tenor sax, is his only outing as a leader. It’s a true gem, though. Harris’ broken, hesitant squonk gives “It Might As Well Be Spring” a plaintively delicate vulnerability, and Webster’s huge tone and vibrating reed are sensuous as ever on “Crazy Rhythm.” It’s the juxtaposition of the two on “I Surrender Dear” that’s truly transcendent though; smooth and broken, hesitant and suave, one of the greatest forgotten “good old good ones,” as Dick Buckley used to say.

Chuck Berry, “St. Louis to Liverpool”, 1964

This was released in 1964, after Berry had spent 20 months in prison. It’s a conscious effort to engage with the wave of bands that had been inspired by his music, from the use of overdubbed vocals on “Little Marie” to name-dropping the Beatles on “Go Bobby Soxer.” “St. Louis to Liverpool” also tends to make all those bands look a little puerile, Certainly, the Beach Boys weren’t singing about child custody struggles, and John Lennon wasn’t writing lyrics to match “It’s a bobby soxer beat

/And you can rock it any way you wish/Work out, bobby soxer,/you can

Wiggle like a whimsical fish.” Nor did the Stones ever have a guitar solo as hot or cool as Berry’s in “Promised Land,” which manages to evoke both tough electric blues and blazing Nashville picking (Berry was a country music fan of long standing.) And that doesn’t even get to the still-funny-after-100-listens “No Particular Place to Go,” and the fierce instrumental “Liverpool Drive”. Berry is usually thought of as a singles artist; partially as a result, “St. Louis to Liverpool” is rarely considered in the pantheon of the top rock albums. It should be though.

Doors, “The Soft Parade” 1969

As rock, the Door’s were always strained, pompous and lumbering. This is the one album where they turned that to their advantage. Inevitably, fans hated it — Rolling Stone said the band was “in the final stages of musical constipation.” (http://www.rollingstone.com/music/albumreviews/the-soft-parade-19690823). That comparison seems particularly inapt; the Doors here are anything but tight. Instead, the album lurches from track to track, strings and brass spurting seemingly at random, blues riffs flailing, Morrison staggering from odd, vaguely offensive tribute to Otis Redding to hippie enthusiasm to portentous declamation (“You cannot petititon the Lord with prayer!”) to outright doggerel (“The monk. Bought. Lunch!”) The result is something like the Shaggs meet Shatner; a miracle of trashy incoherence. “The Soft Parade” is both humiliating self-parody and the only time Jim Morrison ever made good on his claims to genius.

Sadistic Mika Band, “Hot Menu”, 1975

Sadistic Mika Band was an influential Japanese band, but this particular album doesn’t seem to have been much heralded over here. Nonetheless, it’s my favorite of theirs — a quintessential 70s fizz of lounge fuzak. If Steely Dan composed a blaxploitation soundtrack, it might have turned out something like this.

Sonny & Linda Sharrock, “Paradise” 1975

Guitarist Sonny Sharrock played with Miles Davis, but he’s still relatively unknown, perhaps because he refused to fit neatly into the “jazz” label. Certainly, his second album with his then wife Linda is uncategorizable. There are repetitive spiky “On the Corner” style funk riffs, cheesy keyboard grooves, dissonant free jazz interpolations, blues licks, and through it all Linda’s Yoko-Ono-goes-to-church garbled combination of moans, shrieks, and speaking in tongues. All the nuttiness is held together by an undeniable strain of soul. Many folks have draped themselves in the mantle of Mingus, but “Paradise” may be one of his truest children, not least because it sounds so completely unlike him, or anything else.

Marty Stuart, “Busy Bee Café”, 1982

Stuart had some success on country radio later in the 1980s and 1990s, but this, his second album, was mostly ignored at the time and since. You can see how folks overlooked it; it’s a gloriously relaxed affair, with Stuart’s lightning bluegrass picking sliding into one easy groove after another. The album is a tribute to Stuart’s influences and friends, and so Johnny Cash shows up on a number of tracks, just to remind you that he wasn’t as aesthetically lost during the 80s as Rick Rubin would like you to believe, while the wonderful Doc Watson trades vocals on the twin guitar “Blue Railroad Train”. “Boogie for Clarence” is a virtuoso tribute to the bluegrass guitarist. “Busy Bee Café” is a quiet masterpiece, filled with love.

Womack and Womack, “Love Wars” 1983

Womack and Womack make moderate soul for middle-aged folks who want to bob their heads rather than shake it on the dance floor. The lack of urgency probably explains their relative obscurity — and it’s also why “Love Wars” is such a great album. The tracks sway and insinuate, as Cecil and (especially) Linda’s vocals dripping with longing, knowledge, and vulnerability. It’s a similar psychic space to Van Morrison’s “Astral Weeks,” and I’m not always sure which album I like better.

Doughnuts, “Age of the Circle” 1995

The Doughnuts were apparently marketed as a straight edge band, but those thick, brutal guitars, the grinding tempos, and even the strained, half-shrieked vocals seem less akin to punk than to the death metal scene in their native Sweden. Similarly, the lyrics aren’t about hardcore snottiness and political engagement; they’re about filth and impurity and despair —songs like “Who’s Bleeding?” are a riot grrrl take on metal’s traditional body loathing. Maybe the Doughnuts are unknown because of the punk/metal genre confusion, or maybe the U.S. just wasn’t ready for an all-female Swedish band that sounded like it pulverized multiple grunge acts before breakfast. Either way, “Age of the Circle” is a lost classic.

Michio Kurihara, “Sunset Notes” 2007

Best known for his work with Japanese collective Ghost, Kurihara’s solo album has a lot of that band’s psychedelic fire. It’s also a showcase for his range as a guitarist, though; not just the high volume Hendrix lilt of “A Boat of Courage,” but the gentle acoustic backing of “The Wind’s Twelve Quarters” or the crunchy guitar pop-hook worthy riff in “Pendulum On A G-String” and the oddball high-volume March of “Do Deep-Sea Fish Dream of Electric Moles?” One of the most sublime records of the 2000s that didn’t show up on anyone’s best-of lists.