______

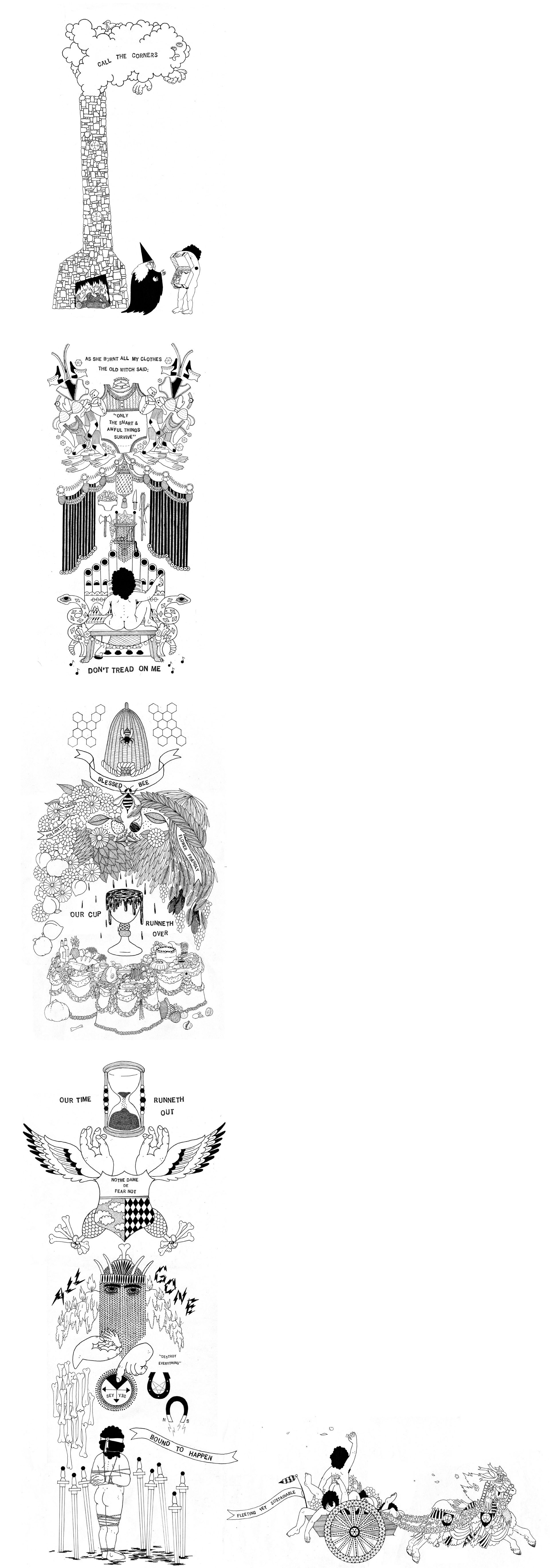

Be sure to click on the image to get a larger view.

This is part of the Gay Utopia project, originally published in 2007 . A map of the Gay Utopia is here.

______

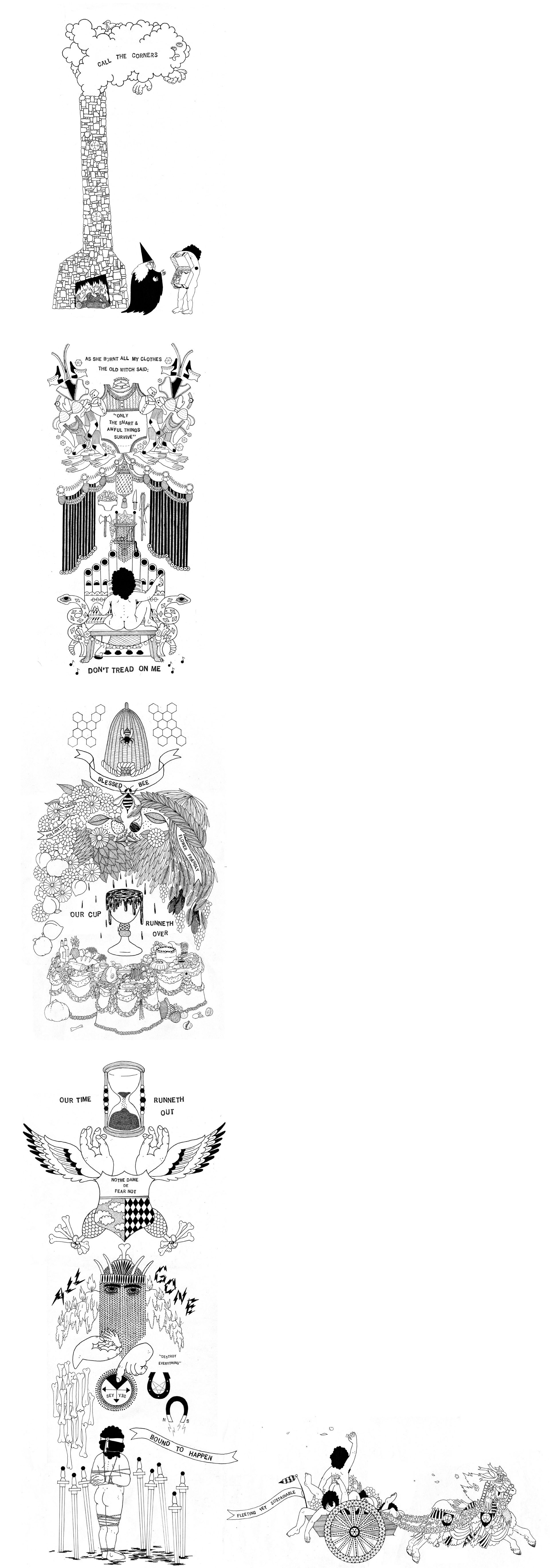

Be sure to click on the image to get a larger view.

This is part of the Gay Utopia project, originally published in 2007 . A map of the Gay Utopia is here.

The current “Golden Age of Television” is not so much a revelation that TV can actually be good, but that stories are often more impactful when told the long way. Plot arcs develop on a slow burn, and the audience has time to form intense emotional attachments to even minor characters. On the flip side, even a great television show will spend its initial few hours building up to that magic, pivotal moment that justifies the hype. The Sopranos first breaks out of its shell and becomes a harrowing nocturne in “College,” (season 1, episode 5,) and Breaking Bad clicked during the wrenching intervention scene in “Grey Matter” (also season 1, episode 5.) So a part of me can’t fully dismiss True Detective only after the first episode, even if I feel like I spent an hour of my life watching the unholy union of Twin Peaks and a dick measuring contest.

Dominick Nero at The Gothamist, and other besides, have already pointed out a striking similarities between Twin Peaks and True Detective here—(but watch out, there are spoilers in it. I try to remain spoiler free below.) Nero writes, “Rust Cohle and Marty Hart are arguably the 2014 equivalent of FBI Special Agent Dale Cooper and his gruff buddy, Sheriff Harry S. Truman. The dreamer and the lawman, the weirdo and the straight guy—Lynch made this detective dichotomy a primetime staple over 20 years ago. And although Nic Pizzolatto is by no means a Lynchian storyteller, True Detective owes a lot to the short-lived ’90s series. Themes of existentialism, pagan naturalism, and the futility of old-fashioned Americana (in the north or the south) pervade both shows, making Pizzolatto’s efforts largely indebted to the elusive David Lynch.” In both shows, a young woman’s corpse is discovered, bearing ritualistic, sadomasochistic markings. It turns out she was a prostitute, and involved in some heavy shit. Wacky lawman pays attention to strange details and throws out high-falutin anthropological language, while straight-shooting lawman quietly bemoans the end of human decency.

I couldn’t read Nero’s case in full, because I don’t want to know the ending of True Detective yet. He articulates the stylistic differences between these shows, but perhaps gives too much credit to the post-Katrina nihilism that Rust Cohle and the show are meant to embody. In episode one, Cohle struggles to say anything that the Nietzchean teenager in Little Miss Sunshine wouldn’t have. The Laura Palmer-counterpart is named Dorothea Lange, a fact made even hokier by the show’s bristling self-importance. Twin Peaks is goofy and over the top in many ways, but the over-cooked, baroque Americana of True Detective’s opening sequence takes the cake. It’s like someone watched the first five minutes of True Blood and was like, “This, but darker! And with more strippers!”

Not to mention the first episode’s Frank Miller-esque issues with women. Twin Peaks had the decency to star lots of fascinating women, make Laura Palmer a character, and dramatize the bizarre, domestic fall-out from her death from episode one. Here we have Madonna and Whores, prostitutes and the melodramatic staple of the good-wife back home. And a sassy black secretary, who so far has only been a sounding board for Hart’s even sassier joke. This does not bode well, but there are seven more hours to go. I’ll return with an update upon episode five, and then the finale. It just might take me a few months to get there.

Every once in a while I’ll get an email from someone who wants to know. “Whatever happened to that graphic novel you were working on? Did you ever finish?”

Discards. I worked on it for four years, completed more than three hundred pages while working full-time as a high school art teacher. And now it sits in a box in my closet, unread by all but a few friends, several of whom largely hated it.

What went wrong?

I’m still a teacher. I look at the pile of effort and time and in the right light I see something that might be useful to another cartoonist. I did after all make it that far. Hundreds of pages of finished comic art is in itself nothing to sneeze at. And there’s no doubt in my mind that those hundreds of pages, along with my high school teaching, brought me the skills that I have today, skills that employ me as a freelance illustrator, even if my cartooning itself isn’t in much demand these days.

I was twenty-six when I started, a high school teacher with an almost fevered desire to work, to make things, to bury myself in the aspects of my life I could control. For several years, making Discards provided me with the focus I needed to forget all the other things in my life that were making me miserable.

But somehow, of all the projects I’ve been involved in, this was the one I was unable to drag across the finish line. What went wrong?

But first —

There are reasons I got as far as I did, things I did that I would recommend to anyone pursing long-form comics. For one, I wrote a script — multiple drafts, in fact. The story started out as prose, a manuscript called The Three Thrift Kings. On second revision it lost its title along with most of the text, and became Discards.

The first draft was a loosely interconnected set of stories largely set at a thrift store in rural Florida. The protagonist Michael (I know, I know) has returned to his childhood home for unspecified reasons and takes a job as a janitor at a thrift store. It’s a sort of Pilgrim’s Progress, in a retail outlet, with drugs and lots of monologues about video games.

As a first draft, the story was a structural mess. I had written it as a receptacle for a series of autobiographical anecdotes about my time as a janitor, back-up man, and finally furniture-electrical pricer at a large thrift store in Casselberry Florida. The smaller nested anecdotes were stories I had refined over a long period of story-telling, but the central plot that linked them all together had been grafted on later in the process. (This too was a “found” element. After talking with a fellow teacher about all the strange things I had encountered working at the store, he told me about one of the strangest jobs he had ever worked — cleaning out evicted properties. His story of finding a stash of drugs, and the subsequent return of the owner of said drugs, would provide the missing through-line necessary to make a coherent story out of first draft.)

The second draft refined the physical environment of the story until it took place in essentially two locations– Michael’s house, the thrift store, and the walk between the two. It also strengthened the main events of the narrative by introducing those strands of plot earlier on. In short, it was structurally sound, something that would have been impossible to do had I tackled the pages graphically directly from the onset.

The setting for the story was visually rich as well, and I knew that my intimate knowledge of the minutia of the environments I would be describing would make for interesting comics.

After completing the second draft of the script, I made my second smart move – I drew layouts for the entire book.

Years of studying page mechanics, and the two or three hundred pages I had drawn in my life so far, meant that the layouts came easily, once I warmed to the task. After some initial slowness, I worked my way up to a speed of about 20 pages of layouts a day, working on sheets of discarded paper folded in half, mainly to discourage myself from feeling too precious about my drawing.

In fact, the faster I worked, the better things seemed to go. If I got bogged down on a page, trying to figure out the spacial mechanics of a scene or movement of the characters or placement of dialogue, I’d just crumple it up and continue on another sheet. After a few days of this my layouts were getting much stronger, even as my drawing itself got looser and looser. By the end of the month I had laid out the entire 400 page book.

Not having a final length in mind led me to expand and contract sections at my own whim, and I brought an almost perverse joy to extending certain sequences that had in the script been only a sentence or two of description. Other scenes were recast dramatically, especially dialogue-heavy scenes, which often had added physical action as my “actors” took over from my writer.

And if this were a happy article about personal fulfillment and artistic success, this might be where I would end, with the satisfied artist and his stack of folded copy paper, a readable story in his hands mere months after first imagining.

But I’m afraid that’s not what happened.

What am I looking at, and why do I care? Discards, page 25

When I started Discards, I had some experience in pen and ink, with a wide variety of tools and textures at my command. But I had virtually no experience working for reproduction. By the time I had drawn my first 50 pages, it was clear two things were already very wrong.

For one, I was working at a scale much too large to be useful for me. Specifically, I was working with an active page area of 11” x 15”, i.e. double the size of my folded letter-paper layouts. Huge originals plus a mania for tiny little lines and an initial fear of bold application of blacks equaled pages that seemed anemic and washed-out, no matter how many layers of lines I added.

And all those little lines added precious time to each page. My work sessions took place every day after ten hours of teaching. I timed them. Each page was taking between 10 and 15 hours to complete, the majority of this time spent embellishing. “Well, you’re fearless, aren’t you?” cartoonist Jim Woodring told me once, staring at a page consisting of nothing but shopping carts in a darkened room. I don’t think he meant it as a compliment.

Even worse than the huge amounts of largely invisible effort was the waste caused by ineffective designs or “off-model” characters.

Somewhere, some when, some genius said it first. “In comics, style is way less important than consistency.” Whomever it was, I’d like to shake their hand, and then ask them to please build a time machine and head over to Seattle circa 2009 so that they can let me know in person.

My initial designs for my characters just weren’t very well-thought out. They weren’t easily distinguished from each other, not by body type, not by facial structure. And as a consequence of that initial failure, I just kept on tweaking even as I produced “finished” pages.

The result of this was a stylistic mishmash, where characters were sometimes only identifiable by the type of screen-tone applied to their hair. Had I applied some basic rules of design to differentiate them from each other at the start, it would have saved me a lot of grief.

This “design drift” was made even worse by the rudimentary nature of my cartooning. As an observational draftsman, I had some skills to draw upon at the start of the project, but as a cartoonist producing stylized forms from my imagination, I had a lot of work to do. And the better I got at these tasks, the more inadequate the previous pages seemed to my eye.

The crudity of the drawing was made worse by the surface polish of the inking and rendering.

Sylistic drift of this kind would have to be very dramatic to be visible over the time scale of, say, a ten page or even 25 page story. But a graphic novel is one contained unit. You can hold it in your hand, flip through it, stick your fingers between the pages. The first panel exists with the last in perfect simultaneity, no matter how much time passed in the process of creation.

This is not unlike the difficulty of assessing the work of, say, Dave Sim and Gerhard and their 26-year project Cerebus. The early issues of Cerebus, crude as they could be visually, still stood unified stylistically as they appeared, issue by issue. But as collections, the early work reads very differently. Much of this difference is undoubtedly due to this stylistic drift. What was an asset in the serial format (improvement of the artist over a prolonged period of time) becomes a liability when the format is changed.

Had I been publishing or otherwise making these portions of Discards publicly available as I worked, it’s possible that I would have been able to make peace with the early portions of the book. But as it was, unseen by anyone save my fellow Seattle cartoonists, the early pages shortly seemed unbearably crude to my eyes. And the more I developed, the wider the “awkward” phase of the book seemed to be.

“Be like a shark,” cartoonist Jon Morris tried to warn me. “A drawing shark. Don’t stop swimming. Just keep eating stuff.” And had I been working on a series of short stories, something where each unit could be its own contained unit, then I might have persuaded myself he was right. But this was a novel, dammit. Shouldn’t the first page look like the last?

The real end to all of this wasn’t my frustration with my drawing, or the labor of the large-format pages. I actually managed to correct course on both of these problems mid-way through the book, switching to a much smaller scale, working with more dramatic blacks and incorporating bold brush into some pages, and finally settling in to drawing the characters with an acceptable amount of consistency.

What finally sunk it was this – so much time had passed since the initial idea, I hated the whole story.

It was two cartoonist friends of mine, David Lasky and Helen America, that gave me the bad news that I was making a book about an asshole. He’s completely unlikable, they each told me over tea and cake. Why should we care about him at all?

This was a hard blow. I was, after all, in the process of making a story about someone who possessed many of my memories and experiences, if not always my actions or personality. How could they say something so harsh about him? About me?

And then, with their reactions in mind, I sat down and read what I had made.

I hated him.

Really, I hated me.

Here was a story about someone who is essentially a tourist in the lives of the people around him, who observes them from the comfortable distance of condescension. Several of the choices I made as a cartoonist reinforced these distances – the facial caricature, the dialect. Here, truly, was a book about a brash young man who is in fact an asshole. Who happened to have been based, at least partially, on myself.

I tried a few fixes, specifically, adding a sequence in the very beginning that gives the character some self-awareness of these deficiencies, letting the audience into his thought process a bit while introducing hints as to the events had shaped him into the person he was.

But it was too little too late. The project was definitively killed a month or two later, when I had my first taste of being paid to make things I was interested in. My labor was done, although Discards never would be.

When I think about my brief time making comics for public consumption, I’m struck by the oddity of it all, that my most widely-read comic written and drawn in a single twenty-four hour period, was not labored over in any way at all. How different would my cartooning have been if I had used all the time I spent on Discards making other short, spontaneous comics instead? How many thousands of pages might I have now had I focused on content rather than the pursuit of some awkward perfection?

Of course, who knows what those comics that never were might have been like, and what kind of things they might have said about who I was at that time. Although the unfinished things in our lives can be painful, in some ways it’s the finished ones that are the worst, in that our failures are so clearly articulated by our own labors.

For me, finally, I’m happy for Discards to finally be what it is, a journeyman work in a box in a closet. A personal example of what can happen when you want too much and know too little. And, maybe, an example of how not to make a graphic novel.

Sean Michael Robinson is a writer, illustrator, and musician. You can contact him at LivingtheLine.com, or at seanmichaelrobinson at gmail dot com.

Years ago, when I was learning about cross-cultural communication and the teaching of English, a teacher of mine said that Americans are often considered very friendly by people from other countries. Sometimes, we’re considered overly friendly, overly intimate, especially when we meet someone new. Her example was something like this:

People who are new to English have to learn that when Americans ask ‘How are you?’ we don’t really necessarily mean it. Maybe we mean it a little bit, but not enough to hang around for an extended answer. Sometimes we are really interested in finding out, but more often than not it’s a perfunctory question and it serves as a routinized greeting rather than an earnest or sincere inquiry. (There is an enormous amount of research in discourse studies and conversation analysis about questions and answers.)

Likewise, when we answer with ‘Fine thanks,’ it’s not because everything is necessarily fine, but because it’s ordinarily expected of us. In fact, if we offer more information than that, it could be seen as inappropriate. Under some, rather restricted circumstances, if someone asks ‘How are you?’ we can answer the question honestly:

Usually, though, we reserve honest answers for close friends, spouses, and family members. Most often, though, the question ‘How are you?’ elicits a quick, conventional, standardized answer.

Not all question/answer adjacency pairs are routine, though. In web comics, especially those that are meant to be funny, the question/answer adjacency pair is used to further the humor of the strip. On a first date between a dragon and a transporter malfunction victim in Scenes from a Multiverse, a comic I wrote about before, questions can help uncover and solve problems or at least defuse tension:

There is a degree of similarity between Dragon’s question ‘Is everything okay?’ and ‘How are you?’ Both of them are queries about the state of the interlocutor: feelings, health, overall situation. But these two forms function very differently. In this comic, Dragon is genuinely concerned about how his interlocutor is feeling. We know this in part because of the follow-up, ‘You seem a bit flustered.’

The questions in panel 2 aren’t routine, either, especially since the two characters are out on a first date and attitudes toward dragons seem particularly germane given the situation. But in panel 4, there is another question: ‘Can you believe it?’ I don’t think this question is a routine question like ‘How are you?’ (Some people may call it a rhetorical question, popularly defined as a question that doesn’t need an answer.) This is a kind of question that is a frozen form, a formulaic utterance meant to anticipate/address an interlocutor’s question or comment about a topic or situation.

I’d like to consider question and answer adjacency pairs in two additional comics. One is from the absurdist web comic Wondermark and the other is from Saturday Morning Breakfast Cereal.

The question-and-answer exchange between Batman and Alfred is funny because it so clearly violates our expectations about how the Batsignal works as a call for help. Couple that with the disagreement about computer-mediated communication and Batman’s strong opinions about how it ought to be done, and no one is surprised by the last panel. Even Alfred’s question ‘Are you mad?’ is a query about Batman’s feelings (like ‘Is everything okay?’ in Scenes from a Multiverse, above).

My last example shows how questions and answers can go a long way toward preventing clear communication. (Alfred and Batman have clear communication in the above comic, even though it may be a little bit frustrating for both of them.) This strip comes from Wondermark, and I wrote about it in an earlier post.

The question-and-answer exchange in Wondermark takes the notion to an extreme degree. The conversation starts out reasonably well, but by panel three, the interaction has gone awry. It is easy to see that the forms (the form of the questions and the form of the answers) are perfectly fine. The ‘problem’ (humor?) arises with the content of the answers. The forward motion of the conversation was strong enough to keep the exchange rolling, even if the questioner and perhaps the answerer knew that the train was going off the rails.

The forms of questions and answers in comics of course reflect to a degree our ‘real-life’ experience with them. It is the function of these adjacency pairs that provides a great deal of room for discussion. The three comics I chose are designed to be funny, and the comics artists use adjacency pairs as a linguistic component to propel the humor.

What comics have you read that called your attention to the particular forms of questions and answers?

“The true picture of the past flits by. The past can be seized only as an image which flashes up at the instant when it can be recognized and is never seen again. ‘The truth will not run away from us’: in the historical outlook of historicism these words of Gottfried Keller mark the exact point where historical materialism cuts through historicism. For every image of the past that is not recognized by the present as one of its own concerns threatens to disappear irretrievably.”

–Walter Benjamin, “Theses on the Philosophy of History” (English translation Harry Zohn; Illuminations p. 255)

Fig. 1: Clipping courtesy of the Bridgeport History Center at the Bridgeport, Connecticut Public Library

I wonder sometimes if I’m being followed. I can’t seem to escape from Walt Kelly. R. Fiore’s recent TCJ review of the new Hermes Press collection Walt Kelly’s Pogo: The Complete Dell Comics Volume 1, compels me once again to consider the cartoonist, who died in 1973 and lived his formative years in Bridgeport, Connecticut. The Park City is about thirty miles south of Oakville, my hometown, and Oakville is just outside of Waterbury, where the Eastern Color Printing Company began producing comic books in the 1930s. Of course, I’d heard of Kelly long before I’d read any of his work. He’s on a short list of Connecticut luminaries, along with Nathan Hale, Rosalind Russell, Paul Robeson, and Thurston Moore, but I didn’t read Kelly’s celebrated strip until I was in my mid-thirties. Several years ago, one of my students gave me copies of two of her late father’s beloved Pogo collections. I know you enjoy comics, she said, and you teach them, too, so I think you might like these: Pogo, the first Simon and Schuster collection from 1951, and The Pogo Papers, from 1953. Covers creased, paper tan and brittle, bindings cracked. Her dad, I know, loved these books, returned to them, left them behind for his daughter, for me. I thanked her for this kind gift, but even then, in the summer of 2007, I neglected them. A year later I was asked to contribute an essay to a collection on Southern comics and I remembered what my student had said: You might need these. I think that’s what she said. I’d like to think so, anyway.

I begin with what is probably more than you need to know about me and Walt Kelly because, like Fiore, I, too admire the artist, and, in the years since my student handed me her father’s Pogo books, I’ve written about his work twice: first, in an essay on Bumbazine for Brannon Costello and Qiana Whitted’s collection Comics and the U.S. South (UP of Mississippi, 2012) and again last year for a paper presented at the Festival of Cartoon Art at the Ohio State University’s Billy Ireland Cartoon Library and Museum. In the first essay, which Tom Andrae cites in his introduction to the new Dell Comics collection, I discuss the two scenes Fiore addresses in his review— the watermelon panel from “Albert Takes the Cake” (Animal Comics #1, dated Dec. 1942-Jan. 1943) and the railroad sequence from “Albert the Alligator” (Animal Comics #5, dated Oct.-Nov. 1943). You can read that 2012 essay, “Bumbazine, Blackness, and the Myth of the Redemptive South in Walt Kelly’s Pogo” here or from your local library; the Google Books version does not include the illustrations.

Fiore takes issue with Andrae’s analysis of the black characters who appear in “Albert the Alligator.” While he begins with the suggestion that “Andrae is on firmer ground in denouncing the characterizations in the story from Animal Comics #5,” Fiore then asks that we consider other readings of the narrative:

Once again, however, [Andrae] is sloppy in characterizing [the characters] as “derisive minstrelsy stereotypes.” The conventions of the minstrel show were as formalized as the Harlequinade, and the characters in the story at hand don’t fit them. Further, I believe a more sophisticated and context-conscious reading would come to a different conclusion.

As I read these remarks, I began to wonder, what would a “context-conscious reading” of this sequence look like? And is Fiore correct? Would it reach a different conclusion than the one in Andrae’s introduction?

I attempted just that sort of contextual reading in my Bumbazine essay, in which I trace the impact not only of minstrelsy but also of the rhetoric of the South as redeemer, a concept Kelly inherited from the Southern Agrarians. But any reading that hopes to place Kelly in historical context must take into account the tensions and fractures that exist in his body of work. Kelly is a significant cartoonist not because he was more progressive than other artists working in the 1940s but because he records for us the contradictions in his own thinking and practice.

Fig. 2: Pogo takes on one of the Kluck Klams in a story from The Pogo Poop Book, 1966

Kelly, the child of working-class parents, a left-leaning, often progressive autodidact who, later in his career, would challenge Senator Joseph McCarthy, the Ku Klux Klan, and the John Birch Society, demands our attention because he forces us to ask another question: given his reputation as a cartoonist beloved by students and liberal intellectuals of the 1950s and early 1960s, how could he also have produced works such as “Albert the Alligator,” stories that clearly owe a debt to the conventions of the minstrel stage, and that traffic in derogatory stereotypes? To answer this question, I believe we need to understand Kelly’s nostalgia for his hometown of Bridgeport, Connecticut. One of the flaws in some of Kelly’s early work was his inability or unwillingness to interrogate the images and ideas he’d inherited from childhood artifacts such as, for example, Joel Chandler Harris’s Uncle Remus stories. As Andrae reminds us in the introduction to the Dell Comics collection, Kelly’s father enjoyed readings those stories to his son.

Fig. 3: Image of Bridgeport from Andrew Pehanick, Bridgeport 1900-1960, p. 124

What effect does nostalgia have on us, as writers, as artists, as critics—as fans? When I speak about Kelly, I find it difficult to separate my nostalgia for home from Kelly’s fondness for the Bridgeport of the late teens and 1920s. When I read Kelly now, I am reminded of my childhood in Connecticut, not because Kelly’s comics played any role in it, but because the setting he describes in his essays, for example—the industrial landscape of the Northeast—is also the world of my imagination. By the late 1970s and the early 1980s, however, the brass and munitions manufacturers that had attracted so many immigrants from Europe and migrants from the South were fading. The only traces that remained were signs with names like Anaconda American Brass on redbrick walls of abandoned factory buildings. And the stories, of course, of the men and women who, like Kelly’s father, like my grandparents and great grandparents, worked in those mills.

Fig. 4: My grandmother, Patricia Budris Stango, second from left, at work in 1941 at the United States Rubber Company, later called Uniroyal, in Naugatuck, Connecticut

As I argue in my essay on Bumbazine, Kelly did not write about the U.S. South. Rather, he told stories in a setting that, for all its southern trappings, looked and felt more like New England. The city of Bridgeport, Connecticut, was, in the early twentieth century, as Kelly describes it, “as new as a freshly minted dollar, but not quite as shiny. The East Bridgeport Development Company had rooted out trees and damned up streams, drained marshes, and otherwise destroyed the quiet life of buttercups and goldfinches in order to make a section where people like the Kellys could live.” In this essay from 1962, Kelly might be describing Pogo’s Okefenokee Swamp: “Surrounding us was a fairly rural and wooded piece of Connecticut filled with snakes, rabbits, frogs, rats, turtles, bugs, berries, ghosts, and legends” (Kelly, Five Boyhoods, 89).

Fig. 5: Clipping from the Bridgeport Post, January 14, 1951. Courtesy of the Bridgeport History Center.

Kelly scholars from Walter Ong to Betsy Curtis to R.C. Harvey to Kerry Soper and Tom Andrae have since the 1950s been looking closely at some of these legends. In his essay “The Comic Strip Pogo and the Issue of Race”—along with Soper’s We Go Pogo (UP of Mississippi, 2012), one of the best academic analyses we have of Kelly’s strip—scholar Eric Jarvis points out that Kelly often referred to “his elementary school principal in Bridgeport as a rather nostalgic model of how society should approach these issues with ‘gentility’” (Jarvis 85). Jarvis then includes passages from Kelly’s introduction to the 1959 collection Ten Ever-Lovin’ Blue-Eyed Years with Pogo in which the artist again remembers the Bridgeport of his childhood and that principal, Miss Blackham: “Somehow, by another sainted piece of wizardry, she sent us off to high school feeling neither superior nor inferior. We saw our first Negro children in class there, and believe it or not, none of us was impressed one way or another, which is as it should be. Jimmy Thomas became a good friend and the young lady was pretty enough to remember even today” (Kelly, Ten Ever-Lovin’ Blue-Eyed Years, 6).

As Kelly biographer Steve Thompson reminded us at the OSU conference, however, in other interviews Kelly describes the racism and ethnic tensions in the Bridgeport of the 1920s. So, like Jarvis, I am fascinated by the role nostalgia plays in Kelly’s art and in his essays because, after all, as Svetlana Boym reminds us, nostalgia is a utopian impulse, a desire not so much to recover the past as it was lived but to recall the life we wish we’d lived, in a world that never was. But, if it had existed, what would that world have looked like? “Nostlagia (from nostos—return home, and algia—longing),” Boym writes, “is a longing for a home that no longer exists or has never existed. Nostalgia is a sense of loss and displacement, but it is also a romance with one’s own fantasy” (Boym XIII).

When Brannon Costello asked if I’d contribute an essay to Comics and the U.S. South, I hesitated. My first thought was to write an article on Howard Cruse and Stuck Rubber Baby. Already taken, Brannon told me. Then I asked, What about Pogo? You can’t publish a book on comics and the South without Pogo. A friend later remarked, Why would you write about the South? You lived there for less than a year, and the whole time all you talked about was New England. That’s not exactly what she said. What she said was something closer to this: You hated it there. But, more recently, when I told my friend that I’ve now written two essays about Kelly and the South, she smiled and said, Of course. The more we resist something, the more we are drawn to it. The more I resisted Kelly’s comics, the more I found myself drawn to them and to the South and to the myths of Kelly’s youth—my youth—that I had ignored

So, in reading R. Fiore’s review of the new Pogo collection, I again find myself face to face with Walt Kelly. And I keep returning to Walt Kelly’s early comics not because they transcend discourses of race; rather, I return to them because they include these stock figures and because I believe these early stories, like my student’s gift, offer an opportunity to think and to reflect on how these discourses—how these racist stereotypes—have shaped my life, my thinking, my conduct in the world. I am writing about Kelly because, to borrow a phrase from Walt Whitman, he and I were “form’d from this soil, this air,” and I turn to him because he invites me to dig through that soil, to breath the air again, to remember.

Fig. 6: The final Pogo collection Kelly published in his lifetime (1972)

It is perhaps too easy to say that these early comics are a record of their time. They are, of course; they demand that we investigate and reconstruct the discourses of the era that produced them. But to deny the hurtful and derogatory nature of the images in Kelly’s early work, I believe, is also to deny his power as an artist. The images in these early issues of Animal Comics are ugly, but there is something in them that will not be ignored. In his mature work—read, for example, Ten Ever-Lovin’ Blue-Eyed Years with Pogo, or The Pogo Poop Book, or Kelly’s final collection, We Have Met the Enemy and He Is Us—Kelly breaks with these conventions. And the image he leaves behind is this one: P.T. Bridgeport, the circus bear, the character who was, in many ways, the real soul of Pogo, now old, tired, but more real and true as he stares at his beloved swamp and sees not a pristine wilderness but a wasteland of junk. But even here we find a possibility of hope and renewal:

Fig. 7 and Fig. 8: From the last two pages of the title story of Kelly’s We Have Met the Enemy and He Is Us (1972) (pages 41-42)

I started this post with a quotation from Walter Benjamin (translated into English by Harry Zohn) not for you but for me, as a way to remind myself of the value of interrogating images like the one of Pogo and Bumbazine sharing the slice of watermelon. If we fail to recognize images from the past as part of our “own concerns,” Benjamin argues, we run the risk of losing them, and their meaning, entirely. But here again I have left something out. Benjamin adds this final parenthetical statement to his fifth thesis: “(The good tidings which the historian of the past brings with throbbing heart may be lost in a void the very moment he opens his mouth.)”

So, a paradox: we must look carefully, search for these “flashes,” but we also risk negating them and their meaning when we speak or write about them. But to remain in watchful silence offers no real alternative. We must speak of these things, although, as we do so, we are not speaking about the past, not really. We are instead addressing the pain of what it is to live here, now, with each other and with these discourses that continue to blind and disorient us.

Fig. 9: Two gifts.

References

Andrae, Thomas. “Pogo and the American South” in Walt Kelly, Walt Kelly’s Pogo: The Complete Dell Comics Volume 1. Neshannock: Hermes Press, 2014. Print.

Andrae, Thomas and Carsten Laqua. Walt Kelly: The Life and Art of the Creator of Pogo. Neshannock: Hermes Press, 2012. Print.

Benjamin, Walter. Illuminations. Trans. Harry Zohn. New York: Shocken Books, 1968. Print.

Boym, Svetlana. The Future of Nostalgia. New York: Basic Books, 2001. Print.

Curtis, Betsy. “Nibble, a Walt Kelly Mouse” in The Golden Age of Comics. No. 1 (December 1982). 30-70. Print.

Fiore, R. “Sometimes a Watermelon Is Just a Watermelon.” The Comics Journal. April 3, 2014. Web Link.

Jarvis, Eric. “The Comic Strip Pogo and the Issue of Race.” Studies in American Culture. XXI:2 (1998): 85-94. Print.

Kelly, Walt. The Pogo Poop Book. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1966. Print.

Kelly, Walt. Ten Ever-Lovin’ Blue-Eyed Years with Pogo. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1959. Print.

—. “1920’s.” Five Boyhoods. Ed. Martin Levin. New York: Doubleday & Company, Inc., 1962. 79-116. Print.

Pehanick, Andrew. Bridgeport 1900-1960. Charleston: Arcadia Publishing, 2009. Print.

Soper, Kerry D. We Go Pogo: Walt Kelly, Politics, and American Satire. Jackson: UP of Mississippi, 2012. Print.

Thanks to Mary Witkowski and Robert Jefferies at the Bridgeport History Center for their assistance in locating materials included here from the Center’s Walt Kelly clipping file. Also, I talk a little more about the Walt Kelly panel a November’s OSU conference here.

Hollywood used to keep its political allegories in the subtext, especially when it comes to fanboy franchises with scifi premises and blockbuster budgets. It’s a smart policy. A little political subtext gives a mass consumer product a twist of relevancy while maintaining plausible deniability should some rightwing commentator accuse Hollywood of promoting a liberal agenda. Fanbases can be even touchier, preferring their escapism untainted by cultural context.

I’m not sure how anyone who saw John Carter of Mars (and I know that’s a small subgroup) could not acknowledge its all-but-overt parallels to the war in Afghanistan and global climate change—and yet when I mentioned these at a fan site, I was accused of imposing a political agenda on an innocent Disney movie. Iron Man 3 fans couldn’t pretend that a soldier dressed in a metallic flag didn’t bear at least some relation to the U.S. military—but that didn’t require every viewer to see Tony Stark blowing up his armada of remote control suits as a condemnation of U.S. drones policy. Ditto for Star Trek Into Darkness. Not only do you have nefarious drones run by a secret and unregulated government agency, but a rogue Starfleet ship named Vengeance reenacts 9/11 in a CGI orgy of collapsing skyscrapers.

That’s what used to pass as subtle in Hollywood. But now Captain America: The Winter Soldier pulls off the allegorical kid gloves. As Michael Phillips of the Chicago Tribune points out, the movie “bemoans America’s bloodthirsty, weapons-mad impulses” and, according to the Washington Post’s Zade Rosenthal, it taps “into anxieties having to do not only with post-9/11 arguments about security and freedom, but also Obama-era drone strikes and Snowden-era privacy.” Both reviewers are right, but since they each afford only a sentence to those political messages, a reader might think we’re wading into the gray zone of interpretation. We’re not.

The latest Marvel Entertainment installment is about the head of a massive government agency struggling to the do the right thing for his country. His name is Nick Fury, and the fact that Samuel Jackson and Barack Obama are both black is the film’s only coincidence. Robert Redford plays the Bush-era neocon on Nick’s rightwing shoulder while on his idealistic left Captain America still believes in American values like freedom and honesty and not shooting people because surveillance software predicts they’ll commit a crime.

The plot mechanics pivot on three mega-drones and their promise of Absolute Security. They lurk in a shady labyrinth beneath an innocuous government office building, and when they come alive all of America will finally be safe. At least that’s what Fury-Obama wants to believe. But Redford was beamed in from a Cold War espionage film to provide an internal Evil Empire. It’s not just that the NSA-SHIELD has been infiltrated; the organization was corrupted from its founding. That’s what President Eisenhower warned back in 1960. He called it the Industrial Military Complex. Marvel calls it HYDRA. When those three mega-drones go online, they’re going to combine into a Death Star that only the rebel alliance of Captain America and his kick-ass sidekicks can stop.

It’s a familiar formula. Peter Weller played Redford’s role in Star Trek Into Darkness, and both platoons of secret thug agents wear black and neglect to shave. Instead of a villainously superpowered Benedict Cumberbatch we get a villainously superpowered Sebastian Stan, both of whom emerge from cryogenic suspension. Which is not to say directors Anthony and Joe Russo and screenwriters Christopher Markus and Stephen McFeely lack all subtlety. I quite like how the nefarious HYDRA hangers rise from beneath a cement pool that echoes the Lincoln Memorial reflecting pool that Captain America sprints around in the opening shot. And the film’s use of the Smithsonian Museum should win Best Exposition Gimmick of the year. Costumer designer Judianna Makovsky scores points too. When the Captain finds cause to go rebel, he morphs into a white t-shirted, motorcycling James Dean, and when Nick sees the error of his ways, he trades in the leather of his Matrix wardrobe for a hoodie and shades.

That’s how Hollywood would like Obama to dress now too. Like his alter ego, the President needs to recognize that all his well-intentioned spying and droning violate the freedoms he’s trying to safeguard. That’s the film’s overwhelming message. And the fact that it’s being shouted by a massive, profit-hungry corporation says even more. Marvel Entertainment doesn’t represent the liberal left or the libertarian right. They shoot straight down the middle at the bottom line.

I doubt Obama will follow in Samuel Jackson’s footsteps and gut the NSA, but the film’s overt political commentary is drawing votes at the box office, earning over $10M its opening night. Marvel is literally banking on the new anti-surveillance alliance of liberals, conservatives and independents. It’s almost enough to make me long for those innocent days of apolitical, escapist entertainment.

Wine is a great accouterment for villains. Aristocratic and impenetrable, a glass of red can suggest that its drinker lounges about, sipping the blood of his enemies and chuckling evilly from the shadows. White wines code the airy disconnect of the elite, aestheticized and cruelly indifferent of everyman struggles. Hannibal drinks Chianti and eats people, and the merciless denizens of Elysium drink whites at garden parties in space. Wine conveys authority, but it’s a fairly obvious power-play. And a better villain can out-power that power-play. Enter Clarence Boddicker.

Wine is a great accouterment for villains. Aristocratic and impenetrable, a glass of red can suggest that its drinker lounges about, sipping the blood of his enemies and chuckling evilly from the shadows. White wines code the airy disconnect of the elite, aestheticized and cruelly indifferent of everyman struggles. Hannibal drinks Chianti and eats people, and the merciless denizens of Elysium drink whites at garden parties in space. Wine conveys authority, but it’s a fairly obvious power-play. And a better villain can out-power that power-play. Enter Clarence Boddicker.

Kurtwood Smith’s performance in the original Robocop is one of a kind. Boddicker’s smile is vicious, but disturbingly sweet. One moment he squirms with glee, only to be still and deadly the next. He’s the ringleader of a hysterical, trigger-happy gang, which more than anything resembles a group of bros gone wrong. Which is a great reminder for the goonish underbelly of many male-bonding narratives.

But Boddicker doesn’t dominate as much as destabilize. He’s balding and bespectacled, yet emotes childishly. He throws tantrums. He unpins a grenade with his tongue, peering down at his quarry with an odd, come-hither look in his eyes, practically miming to his employer’s recorded assassination statement. Boddicker’s interaction with the one glass of wine in the film is no less subversive. When demanding a cut in the price of cocaine, Boddicker sticks two of his fingers into a drug lord’s glass of Ruffino Riserva Ducale, and then snorts the drops from his fingers. Even better, the drug lord then picks up the glass, and in a bizarre act of social facilitation, takes a sip.

It’s interesting that the wine appears here, in a cocaine factory, and not in the hands of one of the privileged board members of the evil corporation OCP. While it would have been ridiculous for wine to be served at their meetings, its equally absurd for it to appear in Sal’s rock shop. Not to mention that Ruffino Riserva Ducale is prestigious. Karen McNeil deems it a ‘must’ to try in The Wine Bible, “One of the leading producers of traditional Chianti… its Ruffino’s Chianti Claissico riserva called Riserva Ducale that is the jewel in the crown.” Sal’s bottle looks to be contemporary to the ‘80s; a current vintage Riserva Ducale would cost about $25 retail, and about $50 or more in a restaurant. Not a rare or overly expensive wine, but not cheap either, and Sal seems to be drinking it casually. Which is a power statement in itself—Ruffino Riserva Ducale is his house wine, even when it can be barely tasted over the wafting powder. Drinking Ducale in a cocaine factory reduces the wine to an empty signifier of prowess and sophistication. Snorting it is a more honest admission of what it is—a power trip.

Ruffino Riserva Ducale Vinages: 2001 (Standard label), 1953 (Standard label), 1980 (Gold label)…The packaging in the still is definitely from the 80s.

A quick dip into the history of Chianti reveals a stranger layer at play. Up until the seventies, Americans knew Chianti as a cheap, barely palatable wine in a straw bottle. While Chianti must be primarily made with the black grape Sangiovese, misguided Tuscan wine laws permitted—then required– the inclusion of Trebbiano and Malvasia into the blend, which are (usually) characterless white grape varietals that are easy to grow. This stretched the Sangiovese a little further, but watered down the quality significantly. While there had always been a tradition of making Chiantis for cellaring, like Riserva Ducale, their reputation was harnessed to the low esteem for the basic Chiantis.

In the early seventies, Ruffino was one of the first producers to do away with the straw bottle, and presumably decrease the amount of white grapes in the mix. Other producers created “super-Tuscans,” highly lauded, heavy-weight Cabernet Sauvignon blends that often, but not always, included Sangiovese. As these didn’t conform to existing wine laws, they couldn’t be labeled Chianti, and their popularity mirrored the success of the renegade wineries in Napa, California. In order to compete with these non-Chiantis, a “Chianti Classico” designation was created in 1984, which required 80% or more of the blend to be Sangiovese, harvested from only the most traditional growing areas, and the final 20% comprised of black grapes like Cabernet, Merlot, Canaiolo or Colorino. However, the use of white grapes wasn’t completely outlawed until 2006.

Chianti’s reputation progressed enough for Hannibal to name-drop it in Silence of the Lambs in 1991. Parallel movements occurred at the same time in Piemonte, with Barolo and Barbaresco, and throughout the whole of Italy by the late 80s. Italy attracted the attention of American wine critics and their high scores—and a preference for large, fruity wines. For better or for worse, Italian wines changed to fit American palates. In turn, America replaced fantasies of France with rustic Italy, for a variety of reasons ranging between changing kitchen habits and Reaganism. As covered by Lawrence Osborne, in The Accidental Connoisseur,

“Unlike the French, Italians were spontaneous, unsnooty, casual, unpretentiously friendly, and family-oriented—that is, much more like Americans themselves….The huge success of Italian-sounding wines like Gallo and Mondavi had much to do with this commercialized idea of Italy: the Italian family seated around the Mediterranean banquets in golden sunshine. Somehow Italy… had the innocent energy of nature. Like fruit-and-veggie-packed wine itself, that sun-kissed land had about it a whiff of the health food store.”

Meanwhile, Mayor Giuliani was patching broken windows and gentrifying Manhattan, with its heavily Italian heritage, into a safe haven for the wealthy. Film experienced the renaissance of the Italian mob-boss, who took hold of the American imagination with Coppola’s The Godfather in 1972, and was a mainstay by Scorsese’s Goodfellas in 1990, about the time Italian wines went from plonk to paragon.

Sal, wine glass in hand, registers this transformation. Authoritative, barely accented and dressed in a khaki suit, Sal is the image of late-eighties self-indulgence. He barely registers as a bad guy in comparison with Boddicker, who derisively calls him a ‘wop.’ Sal is the image of elevated crime, with a mob pedigree, which he signals not with course stereotypes, but with his enlightened, Italian wine habits. Boddicker’s gesture calls his bluff, replying that crime is always a kind of perversity. By not relying on racial signfiers, and instead including this vinous conceit, Verhoeven can satirize mob movies, and the thuggish indulgence of Reaganism and the eighties, while avoiding actual racism against Italians.

Boddicker might be crazy, but he’s honest about who he is. Robocop attests that crime is chaos, twenty years before The Joker’s declares this in The Dark Knight. Boddicker and the titular Robocop oppose each other like order and anarchy, yet they exist on the same ethical axis, and importantly, are both revealed to be corporate puppets in the end. Sal floats off in cloud-cuckoo land, where there’s honor amongst thieves, or at least a hierarchy. Unfortunately for him, Robocop guns criminals down rather indiscriminately.

This post is the second in a continuing column, What Were They Drinking?!, featured on The Nightly Glass, and occasionally co-posted here on The Hooded Utilitarian.