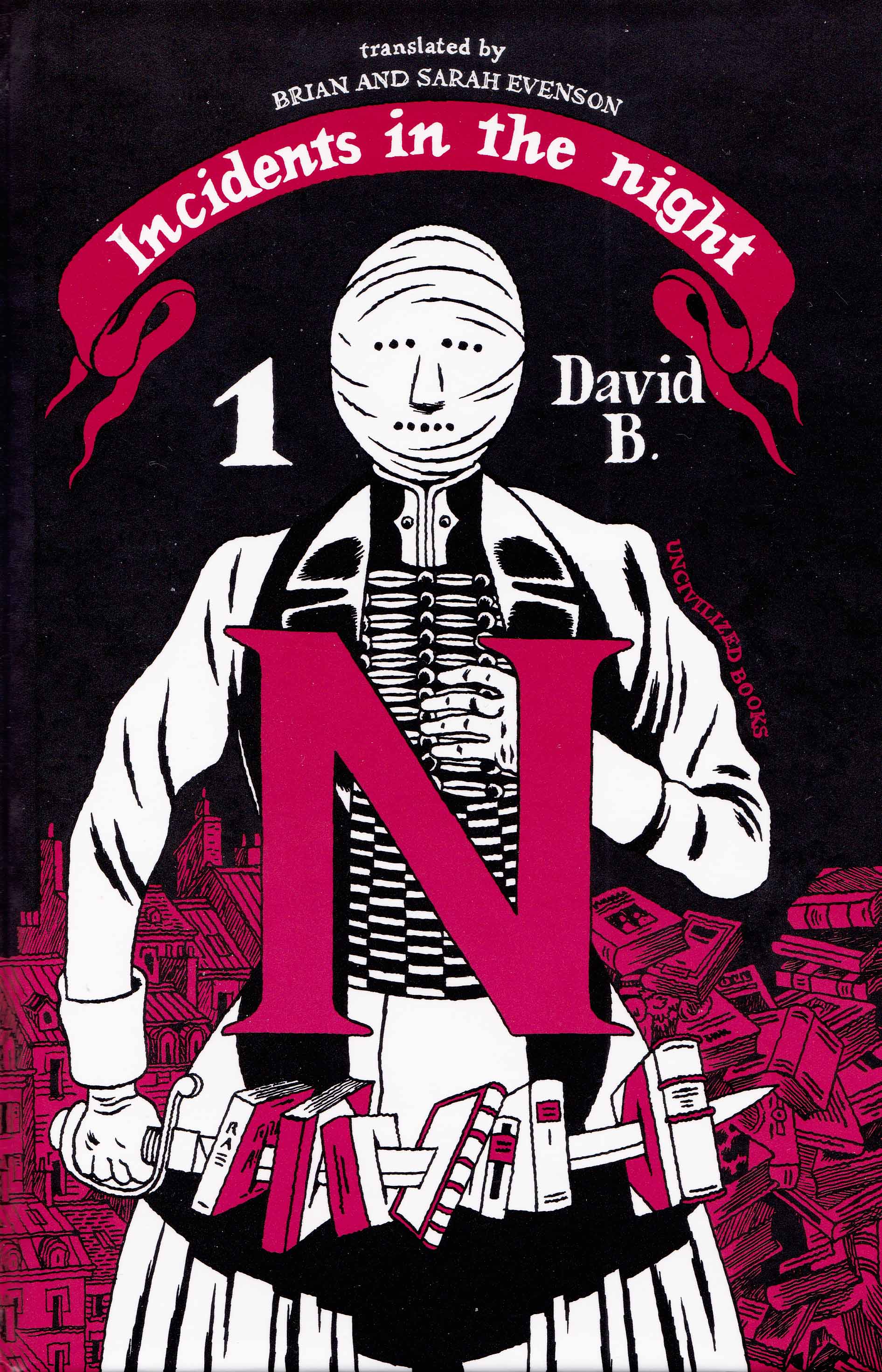

A Review of Incidents in the Night Volume 1 by David B.

Comic translated by Brian and Sarah Evenson

“Like all the men of the Library, in my younger days I traveled; I have journeyed in quest of a book, perhaps the catalog of catalogs.”

Jorge Luis Borges, “The Library of Babel”

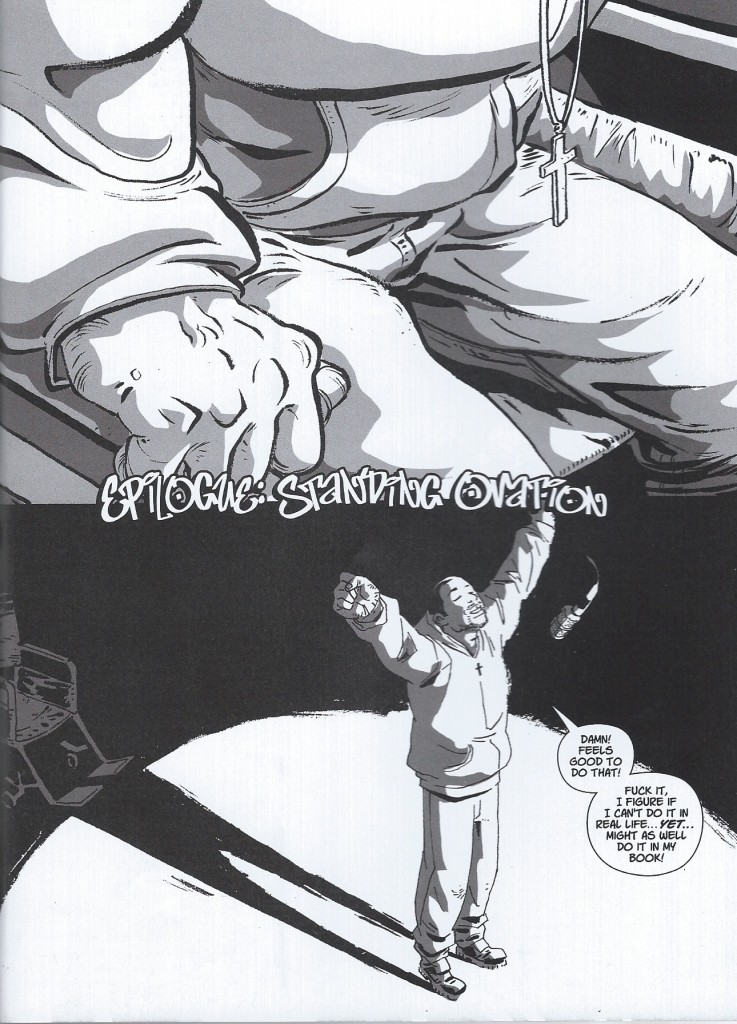

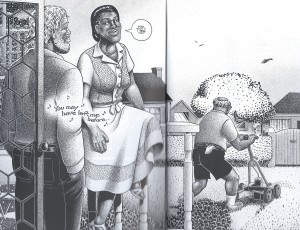

David B.’s Incidents in the Night begins with a record of a dream he had on April 11th, 1993.

In that dream, B. finds himself scouring a book shop where he finds the second, third and then 112th volume of Émile Travers’ Incidents in the Night. When B. awakes, he sets off in search of the physical manifestations of those spectral books, soon finding himself in the capacious literary establishment of a certain Mr. Lhôm. B. is in search of the barely glimpsed record of his nocturnal adventures, a magazine transcribing not only his personal unconscious but the collective unconscious—a MacGuffin; the key to his reveries; his very own “catalog of catalogs.”

In his afterword to the comic, Brian Evenson, evokes the labyrinthine depths of Jorge Luis Borges’ Library of Babel when he considers the existence (or lack thereof) of the many books B. has drawn and enumerated. Lhôm’s library would seem to be yet another repository of all possible books, but it also remains distinct from its illustrious predecessor.

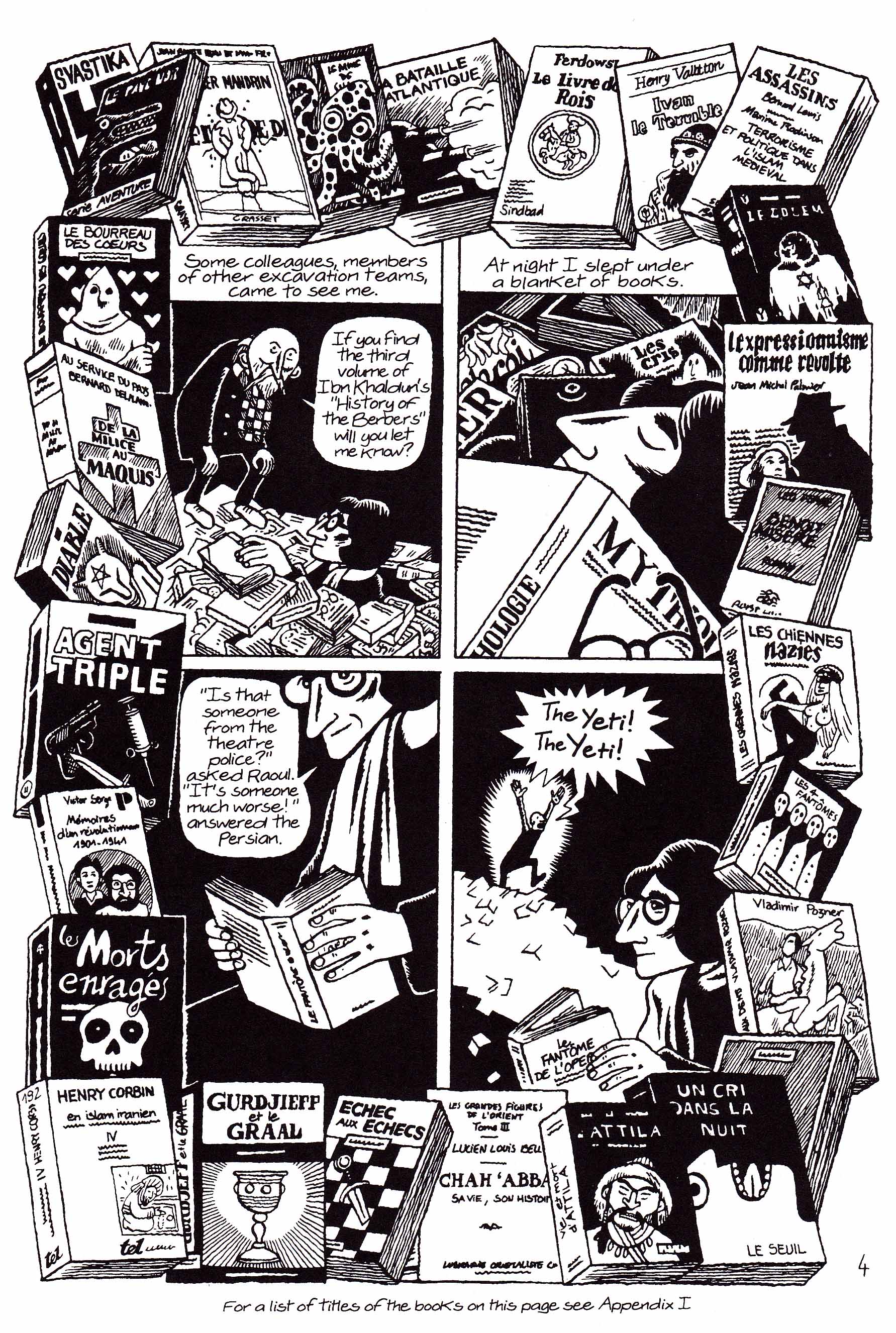

Where Borges’ Library of Babel “is a sphere whose exact center is any hexagon and whose circumference is unattainable,” Lhôm’s cache of illusory knowledge doesn’t have a particularly edifying shape or any semblance of symmetry. It is a place dank and dark with the decaying leaves of thousands of books, enlivened periodically by phantoms. The cavernous space B. traverses is filled with mountains of miscellanea to be conquered. Any discoveries are pleasantly shared among fellow explorers met incidentally among the piles of musty tomes.

At times, the owner-librarian dons the costume of a mythical beast and sets his “wild” dogs on his patrons—the better to excite them. This is a guileless depiction of the romance of reading; each adventurer bound to an elevated conception of Romanticism as epitomized by Casper David Friedrich’s Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog; each hiding a reality much more mundane and disappointing.

B.’s library is no longer “the handiwork of a god” (Borges) but the invention and province of humans. The comic itself is buttressed by tangents sustained by the slightest suggestion.

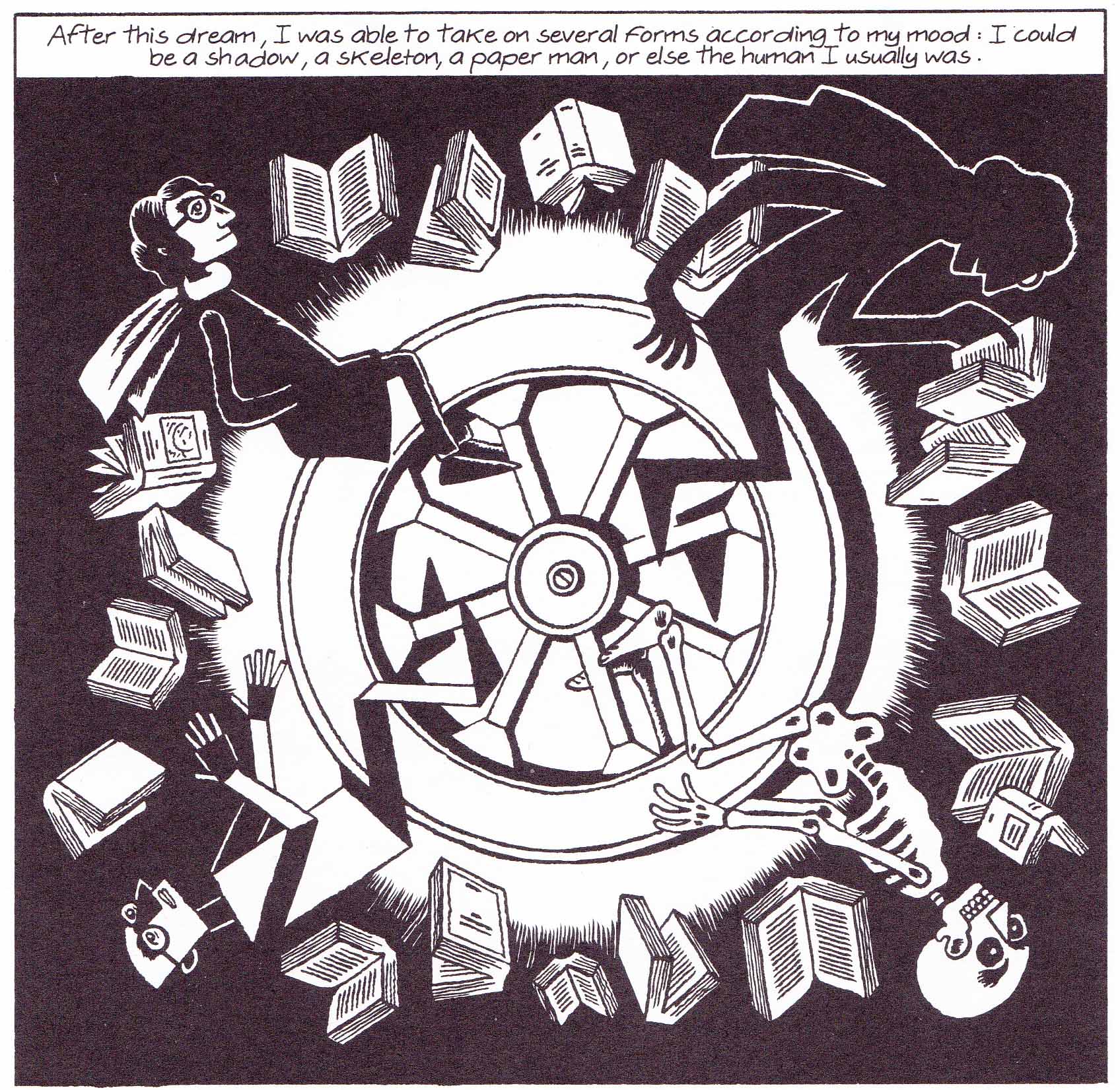

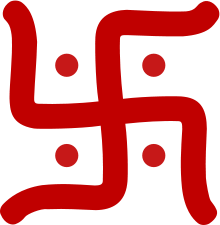

Right at the start, there is the hint of common interest between B. and the keeper of this literary mountain range—the latter’s favorite work is Rene Grousset’s The Empire of the Steppes, a book detailing the histories of the Huns, Turks, and Mongols. With a guide at his side, B. begins a slow trek through the codices of Arabia and hence to South Asia; a purely literary tourist with all the unreliable, second hand knowledge this entails. Among the books unearthed from the “geologic strata” of this region is one bearing a Swastika (sometimes taken as a representation of eternity), the limbs of this symbol prefiguring the four forms the author finds himself split into later in the comic—human, shadow, paper, and skeletal.

These forms are conjoined to a Dharmacakra, an eight-spoked dharmic wheel representing the eightfold path to enlightenment. What the four forms represent is anyone’s guess but they easily play into a number of fourfold concepts in Buddhism: the 4 noble truths; the 4 right exertions; the 4 stages of enlightenment; the division of life into human, heavenly, animal, and demonic forms.

Thus, in the course of a few pages and with the barest of intimations, we have migrated from France to the steppes of Asia and hence to the mountainous regions of the Himalayas; there encountering a legendary creature in its foothills before assimilating an ancient religion of the land. All this without leaving the confines of the author’s apartment, the second hand book shop and France. B. is confined in time and space even as he negotiates the threads of history and geography.

This rendering of the superfluous nature of travel is also found and parodied in the person of a misguided poet by the name of Carlos Argentino Daneri in Borges’ story, “The Aleph.” In that story, the narrator (perhaps Borges) meets the strangely deluded Daneri who haplessly recites his vision of “modern man”, “surrounded by telephones, telegraphs, phonographs….motion picture and magic-lantern equipment, and glossaries and calendars and timetables and bulletins…”; all this rendering the act of traveling “superogatory.” In the same way, the protagonist of B.’s comic, while periodically enunciating his concerns with death, seems perturbed only in so far as physical annihilation would put a damper on his ability to read more books.

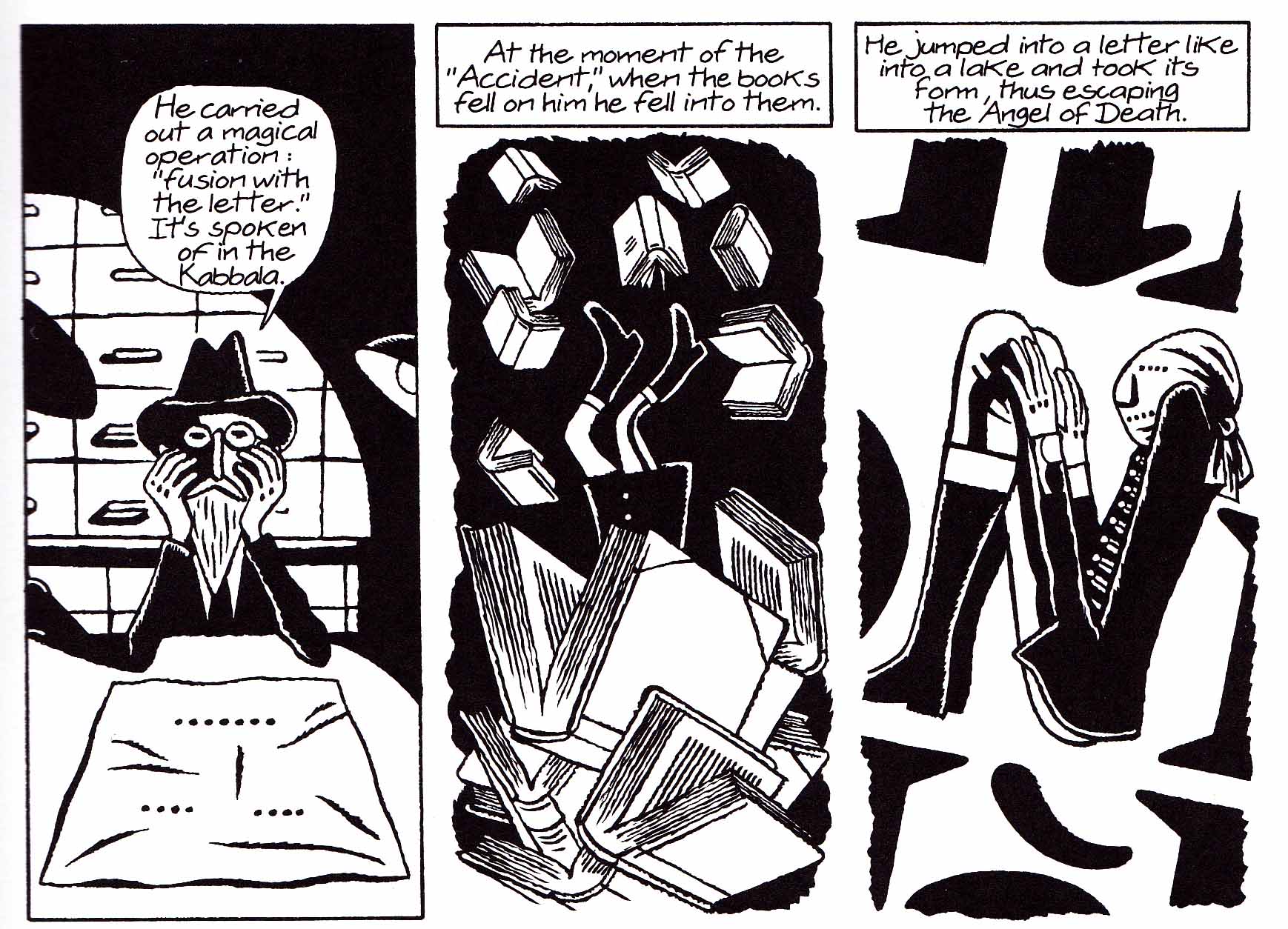

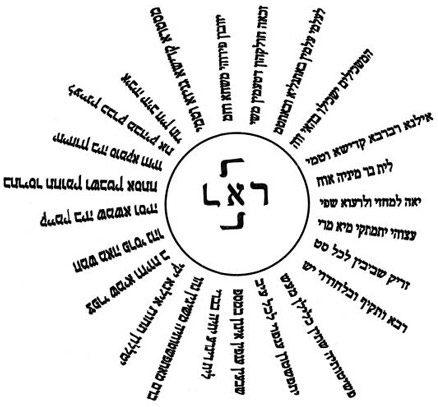

The rabbi from whom B. seeks advice is also confined to his room, negotiating every evening with the Angel of Death; as is the sociopathic instigator of B.’s adventures, the editor of Incidents in the Night (Émile Travers) who escapes death by a Kabbalistic “fusion with the letter” N.

That letter is of course a reference to the Aleph, the first letter in the Kabbalistic alphabet. This, when rotated, takes on the form of that aforementioned symbol of eternity, the Swastika….

…a theme which B. returns to throughout this first volume of Incidents of the Night.

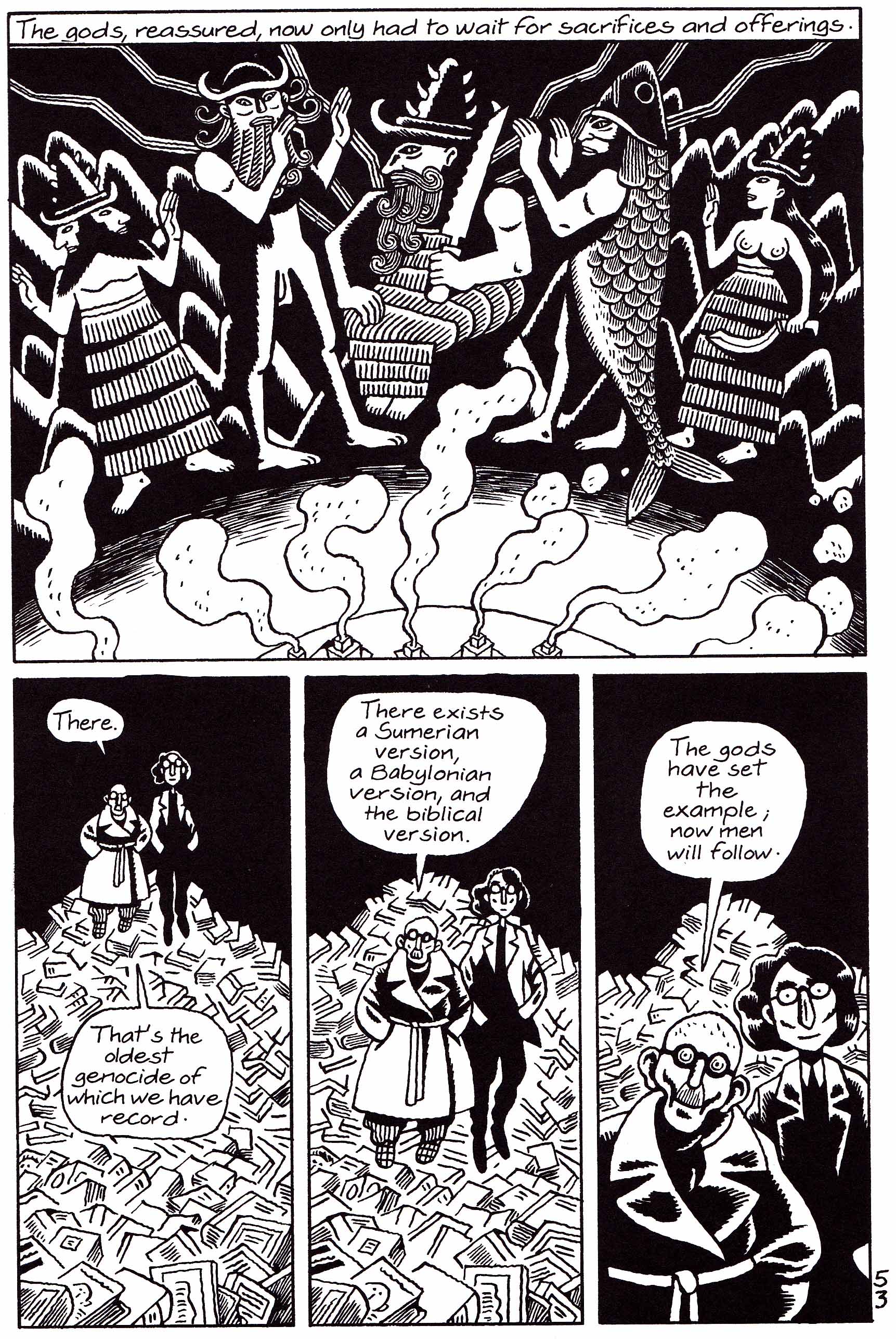

From his drawing board and bed, B. surveys the entirety of time and space—from the Babylonian flood myths to the futile dreams of a Bonapartist (Travers). A similar theme might be found in Borges’ Aleph—

“…the place where, without admixture or confusion, all the places of the world, seen from every angle coexist.”

In explanation of this, Borges opens his story, with a quote from Thomas Hobbes’ Leviathan, (an excerpt from the philosopher’s exposure of false doctrine):

“For the meaning of eternity, they will not have it to be an endless succession of time; for then they should not be able to render a reason how God’s will and pre-ordaining of things to come should not be before His prescience of the same, as the efficient cause before the effect, or agent before the action; nor of many other their bold opinions concerning the incomprehensible nature of God. But they will teach us that eternity is the standing still of the present time, a nunc-stans [the eternal Now], as the Schools call it; which neither they nor any else understand, no more than they would a hic-stans for an infinite greatness of place.”

For B., Émile Travers’ multi-volume Incidents in the Night (a symbol for B.’s dream life) is the Aleph. This might be taken for a simple metaphor but Brian Evenson (in his afterword) ladles on an existential (almost mystical) compact between readers and their books:

“David B. understands that subconsciously we search books for magics that will help us avoid being confronted by our own mortality, and he has made this the conscious subject of Incidents in the Night…We will not find these magics—rationally we know this. But we might still find the promise of them, even as we see within them the reflection of our own future corpse.”

Yet the sideways connection with Borges’ Aleph also suggests something altogether more mundane—a study of influence. If “The Aleph” is in part a tribute to (or parody of) the works of Dante then we might see in David B.’s journey an endless search for influence and precursors. As Borges writes in “Kafka and his Precursors“:

“In the critic’s vocabulary, the word “precursor” is indispensable, but it should be cleansed of all connotations of polemic or rivalry. The fact is that every writer creates his own precursors. His work modifies our conception of the past, as it will modify the future.”

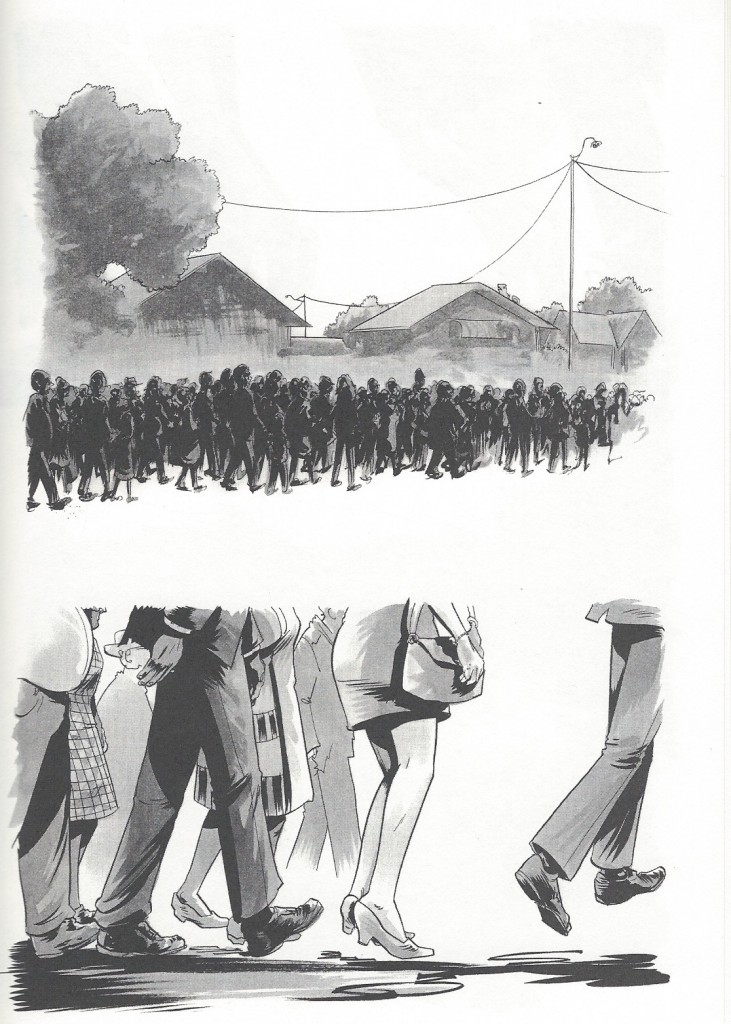

It is a theme which B. applies to the oldest recorded “genocide”—the universal flood destroying all on earth save for the family and animals of Outanapishtim—and also the human wrought extinction of “nearly thirty-five species of mammals belonging to the megafauna” from Paleothic times. In so doing, B. uses a term coined by Raphael Lemkin in 1944 to modify our perception of historical events.

In “The Aleph”, Borges echoes Dante in his acknowledgement of the limitations of words and their (in)ability to convey the transcendent:

“I come now to the ineffable center of my tale…How can one transmit to others the infinite Aleph, which my timorous memory can scarcely contain?”

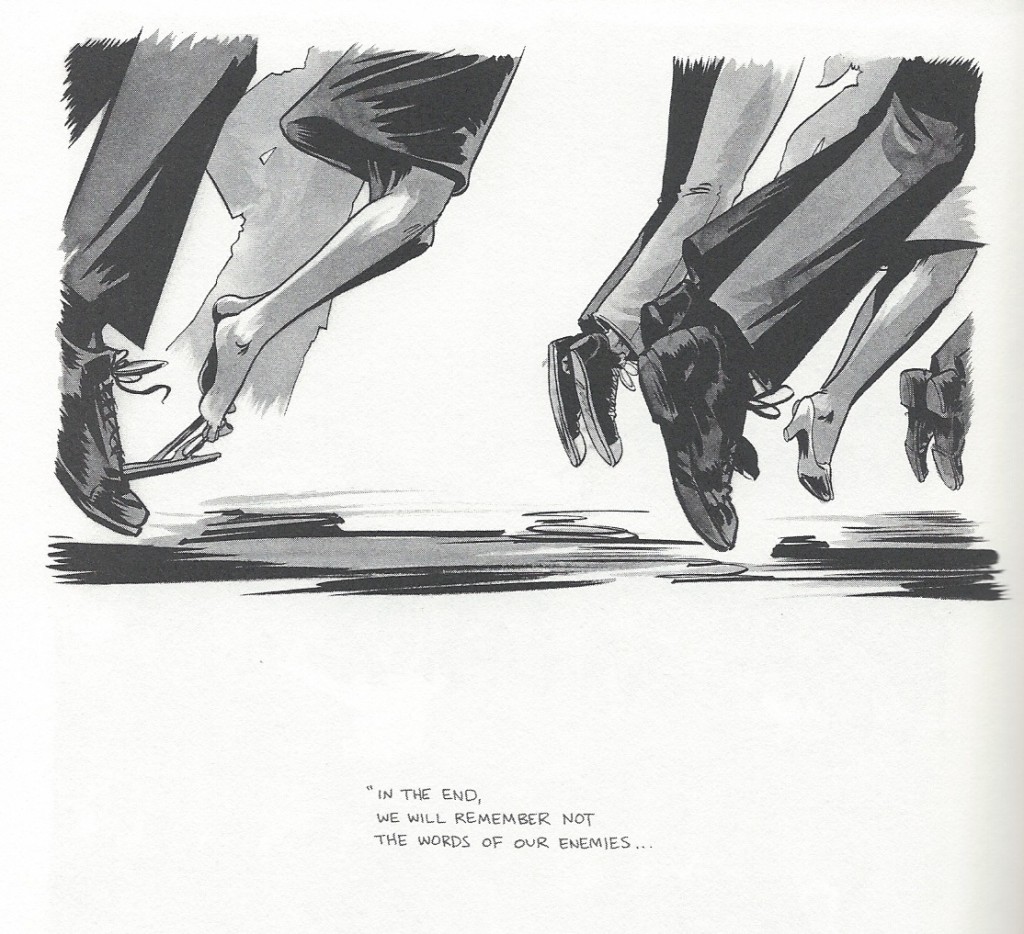

If we find David B.’s comic at once familiar and slippery, it might be the result of a preoccupation he shares with those authors—the interrogation of the inexpressible; in this instance, the basis of creativity. The author and his guide (like Dante and Virgil) wade through an avalanche of books (and afflatus) as they would a sea of corpses; a library of infinite letters and words in the form of a series of hand drawn images—an incomplete transcription of the limits of human language.

_____

Further Reading

See Daniel Kalder’s review of Incidents in the Night for a detailed synopsis of the comic.

The second volume of Incidents in the Night in French.