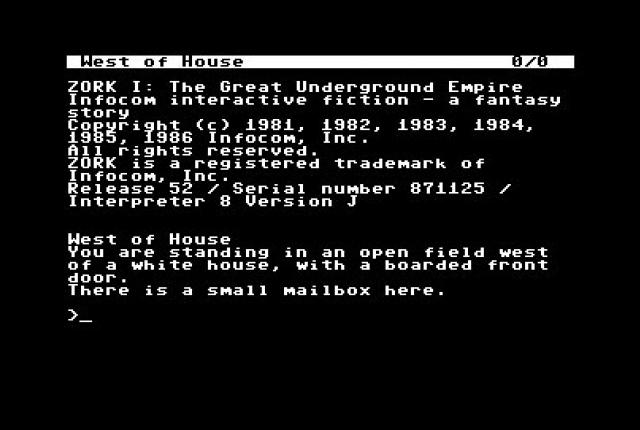

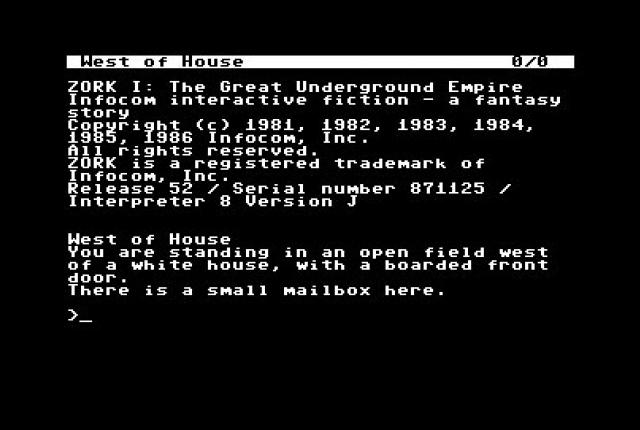

While many gamers have tried (and failed) to work that stupid vending machine in the first few minutes of The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, their engagement with text adventures rarely goes any deeper than that, probably because that game is so damn frustrating. Many early text adventures are as hardcore, unfair, and labyrinthine as games can be; while I respect them deeply, and can’t deny that they gave out a lot of gaming value for the money (these games were meant to torture you for months), I don’t really want to play them. I think most of us have a sense that gaming has moved on from the punishing arbitrariness of early games; Spelunky is punishing enough, but the rules are consistent, established, and learnable, not you-forgot-to-pick-up-this-item-20-turns-ago-and-now-you’ve-been-eaten (although the exploration of those unwritten rules can be as fun as it is frustrating, as I’ll try to explain). The fact that game design has changed drastically, though, doesn’t mean that text adventures have been left behind. It’s easy to think that text adventures (and their close cousins, MUDs), existed only as a stopgap until something better came along, and that text game designers were simply making the best of a bad situation. But imagining that video games progress in a straight line toward graphic excellence is like thinking that Marvelman needs to be recolored because we have better technology now. For years, some of the most experimental and independent work in gaming and storytelling has been carried out in the text-adventure (or Interactive Fiction) community.

Interactive Fiction (also know as IF) is more than the sum of its parts; it’s not a story interrupted by a few puzzles, or a few puzzles with a story grafted on. It’s also not the same as Choose-Your-Own-Adventure fiction (although there are plenty of fine examples of that all over the internet); it may have many endings but a single path, many paths but a single ending, or it may be a non-narrative exercise in exploration. It’s more open-ended than CYOA because it requires the user to generate the text, meaning that reading, problem-solving, exploration, dialogue, and pure aesthetic enjoyment can be combined and manipulated by the reader-player in any way they choose, and that narrative often won’t take precedence. In the same way, you can experience as much or as little of narrative, setting, characters, and dialogue as you like; the closest graphic approximation might be something like Nintendo’s Metroid: Prime (2002), which is highly interactive and unusual in its approach to narrative (but still requires better reflexes than mine). In text games, progress and narrative are integrated in a way rarely seen in graphic adventures, with a heavy emphasis on exploration, and, often, minimal exposition or presentation of the rules.

In this way, what I will call “classic” text adventures (adventures that require text input from the player), also differ slightly from hypertext adventures, like those written in Twine (which I’ll admit I don’t know much about), because they do not require such overt choice; the player has a slightly different kind of control over the way in which narrative and other story and puzzle elements unfold, and their pacing. Twine games like Depression Quest are meeting with great success right now, and I wish I knew enough or had played enough to write more about them. What I can say about Twine games is that the pacing is quite different, and the player is often more limited in what they can do at any given time. This can be useful, especially for slice-of-life games meant to illustrate the experience of living with disability and illness, like Depression Quest. But for me, it doesn’t capture quite the same magic of exploration; many text adventures are, to some extent, about understanding the environment, learning the rules, and understanding when and how those rules can be applied, manipulated, and broken. This accounts for the arbitrary and illogical nature of those early adventures, but it also creates immense possibility for puzzle and world-building; many of the best games are explicitly about learning the rules (Suveh Nux), or about testing the limits of the possible in terms of dialogue (Galatea), action (Aisle), and scope (Blue Lacuna). The experience of limitation is, for me, more compelling when I have to discover and negotiate it; in the same way, there’s nothing quite like realizing that you can do something. Most text adventures operate around the same set of basic rules and commands (and you can always type ABOUT or HELP to learn them), but a lot of the fun lies in discovering how those rules have been changed or expanded. There’s a lot to be said for a gaming experience that’s as much about learning the rules as it is about applying them, as well as about knowing when not to act, and I think it’s a rare experience in graphic games. And when the experience of playing is intuitive and forgiving even as it challenges you to understand and apply unspoken rules, rather than punishing, it’s irreplaceable.

IF is also enjoyable because the barriers to entry are so low for both creators and players; the games are free and usable and just about any platform. The creation of IF languages like Inform and Twine also means that programming these games is easy and can be done with almost no programming knowledge. This means that these games are truly independent, they reflect singular visions, and they allow for much more diversity than the gaming industry seems to be comfortable with. This also means that, even if traditional gaming isn’t your thing, you might find something you like in IF.

It’s better to play these games than to talk endlessly about them, so I’ll devote the rest of this article to introducing a few of my favorites. I’d love to talk in more detail about the experience of reading fiction in second person and the kinds of reading that IF inspires, but I’ll leave that for another article, since I think it can be grasped by playing. For more IF Theory, if that’s your thing, you can visit Brass Lantern, or Emily Short’s Website. There’s a lot out there, and most of it is interesting.

But if you just want some gaming fun, these are some of my favorites in no particular order (there are many more). All of these games can be downloaded for free, and you can run them with a variety of applications for mobile or desktop: Twisty and JFrotz for Android, Frotz for Windows and iOS, and Zoom for Mac. If one of these won’t work for a particular game, most games will tell you what you need; it’s always free and readily available. Many of these games are also playable online, and there are a lot of options out there if you don’t like a particular interface, and a lot of help and info available at Brass Lantern and the Interactive Fiction Database. If you’re interested in writing IF (and you should be!) I recommend using Inform, but Twine is also very easy to use.

Suveh Nux by David Fisher

As a magician’s assistant who accidentally gets locked in a vault, this game takes on the challenges and possibilities of language in a way that no other medium can. A short but challenging puzzle, this game requires you to learn a magical language and implement it in creative ways. While to some extent all of IF requires learning rules and possibilities, this game makes that process apparent in a way that’s fun and fascinating, and requires a lot of quick thinking. Highly recommended as a first game, especially if you love words and puzzles, or if you want to see just what makes text-based gaming a genre worth examining.

Violet by Jeremy Freese

This is a game about the horrors of procrastination and the horrors of dating an MPDG. It’s very cute and very well put together, and I recommend it as a first game, especially if you’d rather avoid science-fiction and fantasy settings. It’s an almost perfect integration of puzzle and story, and the puzzles are challenging but solvable. It’s also worth pointing out that it allows you to quickly and easily change your gender; text adventures in general are great about not gendering their protagonists or allowing for customizability, which is a small thing, but a breath of fresh air anyway.

City of Secrets by Emily Short

Another brilliant game from Emily Short. I could list all of her games here, but this is my favorite. Set in an alternate future, this game casts you as a traveler exploring a glistening city that’s very unlike your home. Unsurprisingly, this city has a few secrets. I haven’t played Bioshock: Infinite, but I like to imagine this as a corrective to Bioshock’s narrative: both focus on gorgeous cities that are more than meet the eye, but City of Secrets has a lot more up its sleeve than “this is bad! shoot people!” This game has beautiful environments, a wide scope, and some built-in graphics that new players will appreciate; they’ll help you navigate the game (it has a novice mode for complete newcomers). Highly recommend along with all of Emily Short’s games: her range is shocking (from punishing classic-style games like Savior Faire to the experimental and user-friendly Galatea), and her games make for excellent YA and adult fiction. Also, since romance is the hottest thing on HU these days, it’s worth mentioning that she’s IF’s best romance writer.

Galatea by Emily Short

A game by one of the genre’s best writers and theorists, this revolutionized the genre when it came out, and it still feels revolutionary today. This game has no puzzles, but is structured as a conversation; you have great freedom to assemble different elements and tell different kinds of stories as you converse with Galatea, the mythological living statue. It’s not exactly like a game, but it’s not like a chatbot or a CYOA either; the interest is in assembling the story, guiding the conversation, and gaining trust and the ability to interact without any guidance from the program itself. The more you discover just how many possibilities there are, the more you’ll be impressed; it’s a one-room game that to me, feels more open-world than any open-world title. That said, if your gaming tastes tend more toward adventure and problem-solving, you might find it slow; it’s a famously love-it or hate-it title.

Jigsaw by Graham Nelson

This game plays like a classic, punishing and inscrutable text adventure, but it’s a delight. Made by the creator of the more famous (and also excellent, Curses!), its a whirlwind tour of the 20th Century structured around a mysterious love story. It’s very long, very immersive and engaging, and probably best played with a walkthrough in hand (I used one for a large number of the puzzles). However, one of the nicest things about IF is that it doesn’t really matter if you can’t solve the puzzles; it’s often not as solution-oriented as other genres. You can still have the joy of reading, exploring, and advancing the narrative, even if you have to be guided through the solutions. (Seriously, one of the puzzles in this game is cracking the Enigma code). If you like lengthy, immersive, and hardcore games, this (and Curses!) are for you. If you just like lengthy and immersive games, play it with the walkthrough open. When you do solve one of the puzzles on your own, you’ll be really excited.

Blue Lacuna by Aaron A. Reed

The opening of this huge, immersive game comes across as a little ridiculous, but give it a chance, and you’ll be rewarded with one of the greatest achievements in recent IF. A beautiful, sprawling, and lonely island exploration in the Myst tradition (although it’s about ten million times less frustrating than Myst), this game has beautiful environments, challenging but solvable puzzles (even for me, the world’s least patient person), and a “story” mode that simplifies or removes the puzzles if you prefer to focus on narrative and exploration. It’s also impressive in terms of its openness and possibility; there are twelve different variables that determine how the story plays out, meaning it’s endlessly replayable. Likewise, these decision points aren’t always obvious; some are clear choices, but others will surprise you. This is a great first game because of its implementation, too; highlighted words help guide you, and allow you to avoid using redundant commands. I’m a sucker for sprawling, lonely sci-fi, from Metroid to Prophet, and this game delivers with a beautiful integration of game and story and a scope that’s very rare for a game developed by a single person.

Spider and Web by Andrew Plotkin

This might be my favorite game. A brilliant espionage game set in a future Cold War; the operative (you) have been captured, and your mind is being probed for the secrets of your unprecedented break-in. I’ll admit I occasionally needed a walkthrough to finish this one, but it’s spectacular. Combining suspense with gameplay that slowly ramps up in difficulty, this game really shows what the medium is capable of. It might be difficult for a first game, but it’s hard to top.

Hoist Sail for the Heliopause and Home by Andrew Plotkin

This is a short and striking, though not necessarily very intuitive game; I like it because the emphasis is on exploration and environments. it’s another one of those lonely, drifting sci-fi adventures and we all know where I stand on those. It even implements a maze (IF’s most reviled trope, inspiring a level of hatred that graphic gaming reserves for escort missions), in a way that’s satisfying and beautiful rather than rage-inducing. Light on plot and heavy on exploration and experimentation.

There are many more games worth trying, like Sam Barlow’s Aisle, a one-turn game with seemingly infinite possibilities, Slouching Towards Bedlam, a horror game which I haven’t played because I’m very easily scared, and Adam Cadre’s revolutionary games, Photopia and Varicella. If you don’t see something you’d like here, you can check the Interactive Fiction Database, or this excellent list of the 50 best IFs of all time, or Emily Short’s list of innovative and notable games. If you’re interested in gaming that feels truly interactive and open, or in the nature of fiction and interactivity, IF is a good place to start. The variety and experimentation you’ll find in the IF community are unmatched in almost any other genre. You may have been frustrated by text adventures in the past, but give them another chance; they’re a unique and rewarding experience.