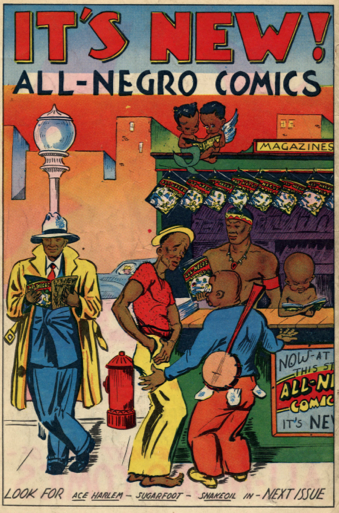

When Philadelphia journalist Orrin C. Evans published what would become the first and only issue of All-Negro Comics in 1947, he boasted that the comic book showcased original stories about black life and adventure with African and African American characters in positions of authority, strength, and trendy style. The comic’s commitment to wholesome, affirming images of black people was underscored by the fact that its artists, too, were African American. Evans even included a photograph of himself inside the cover, thereby confirming the extent to which the comic earned the “all” Negro distinction.

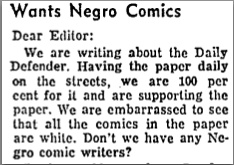

By the mid-1950s, readers of black-owned newspapers had become accustomed to seeing the work of black comics creators like Chester Commodore and Jackie Ormes included among the reprints of syndicated comics. When the daily edition of the Chicago Defender failed to include black comic strips, readers wrote to complain:

This question, posed in March 1956, may sound all too familiar. Nevertheless, much has changed since the 1950s. So much so that “African American Comics” could easily constitute a category of its own (and not just as a display during Black History Month). But exactly what kinds of comics would fall under this designation? Would it only include publications that follow the All-Negro Comics model where black writers, artists, and editors can claim “every brush stroke and pen line” of the final product, or should the term be expanded to any comic about African Americans? Should the stories reflect particular ideological investments? Be recognized by a specialized community of readers and critics?

I also struggle with these questions in my research and teaching in African American literature, where the relationship between naming, visibility, and power is much more pronounced and deeply connected to the exclusionary politics of literary canons. In the classroom, I’ve had to step away from the anthologies that track a narrow, reactionary path from the New Negro to the Black Arts aesthetic. I try to emphasize instead how each successive wave of redefinition attracts new possibilities along with new intersectional silences and contradictions, or as the late Amiri Baraka put it in his 1966 poem, “Black Art”: “Fuck poems/and they are useful.”

The history of African Americans in comics reflects many of these same cultural tensions, but the narrative unfolds much differently. I recently taught a course on “African American Comics” that began with examples of 19th century racial caricature. We studied George Herriman’s comics, discussed All-Negro Comics, as well as genre comics from the 1950s-1970s before moving to more recent graphic novels. I did not begin each new comic identifying the racial identity of its creators, unless one of them made it an issue, for instance, as Christopher Priest did in his terrific introduction to the trade paperback of Black Panther Vol 1. The Client (reprinted here.) The class went very well, but by the end I knew that my title had been inadequate – if not inaccurate, since I also included Aya: Life in Yop City (African, but not American).

So I’m genuinely interested in what people think. What is an African American comic? Is there a way that this term might be useful? Is it too reductive or so broad that it loses all meaning? With Milestone Comics recently celebrating its 20th anniversary, these concerns seem more relevant than ever. We could even extend the question to other social groups – women’s comics? LGBT comics? And remember, Black History Month is upon us. So refusing the question doesn’t mean that someone else won’t try to define it for you.