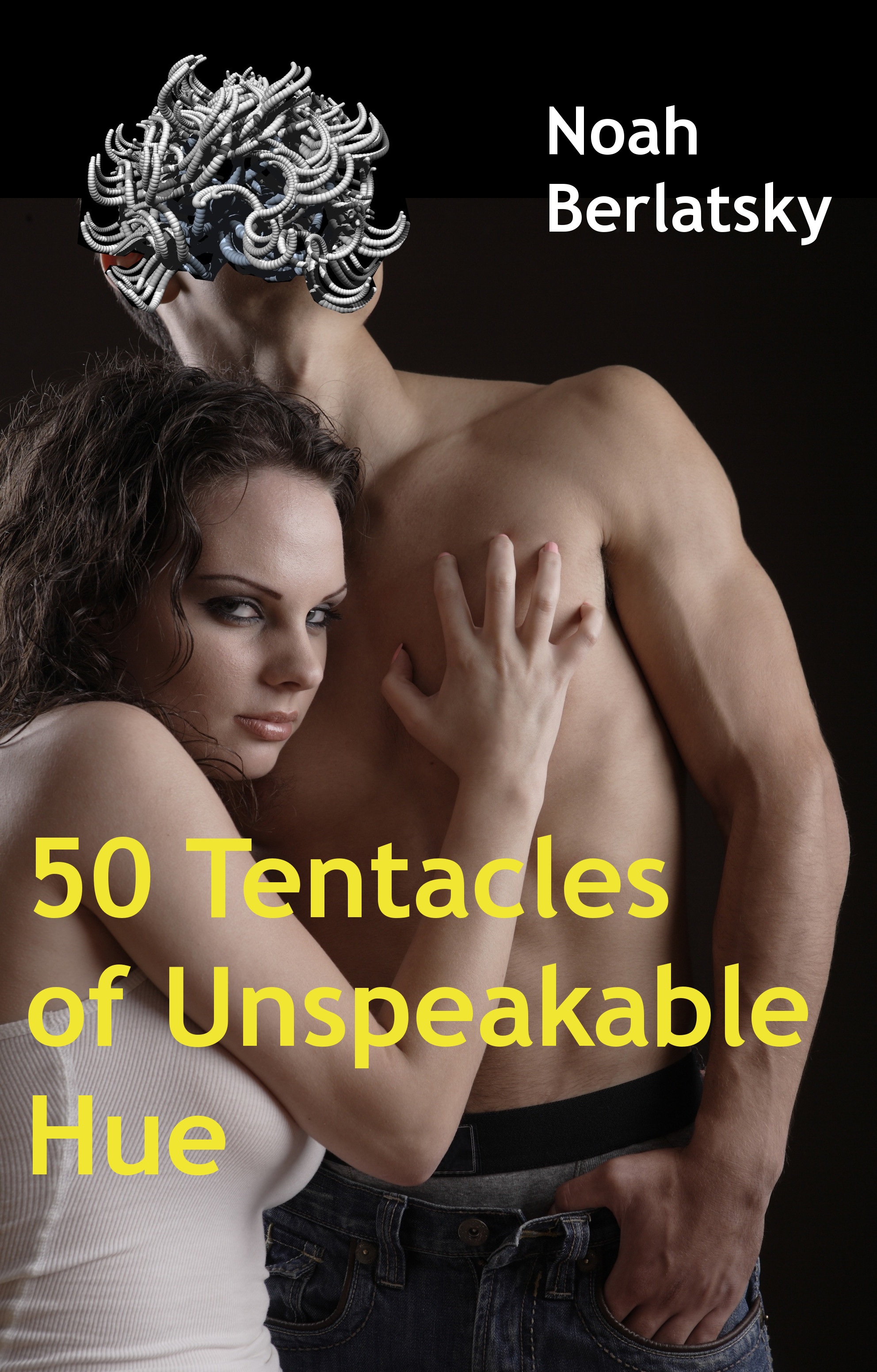

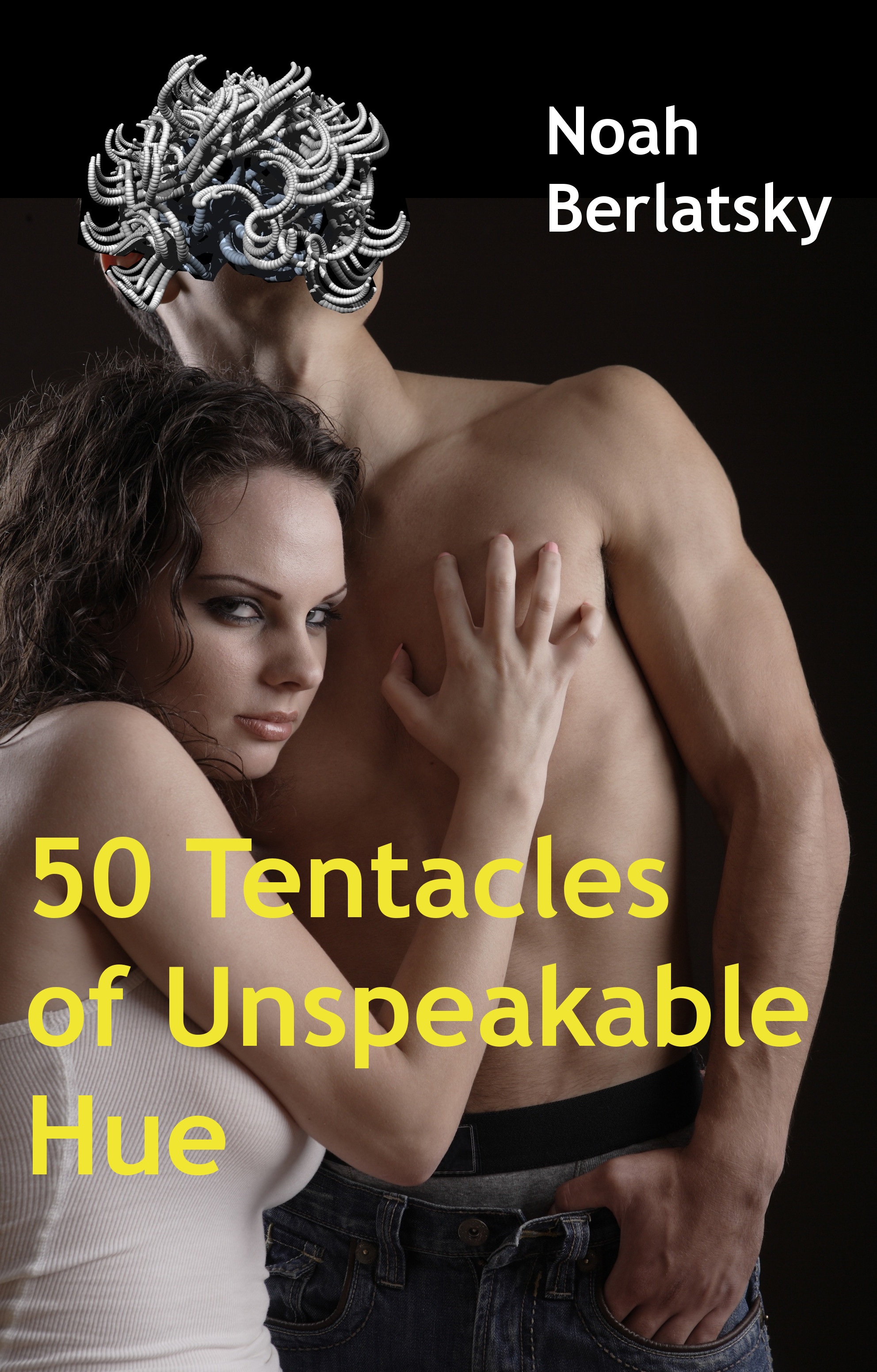

As I’ve mentioned before, I wrote this 50 Shades/Cthulhu mash-up in the hopes people would buy it on Amazon. But no one did. So I thought I’d put it over here instead. If you enjoy it and want to throw me a buck, you can buy the kindle version here. Otherwise, you can just shamelessly freeload.

Oh yeah; NSFW, if you couldn’t figure that out.

_______________

(This is a parody. Don’t sue me, please.)

Oh, my. Even the elevator was intimidating and impressive. I gulped and bit my lip and tried not to be too overly stimulated as the shining glass tube shot upwards through the slick, vertical passageway. On one side, a magnificent view of the Pacific. On the other, the inner workings of Mauve Enterprises, stacked floor on floor, shining in transparent glass. I could see people bustling here and there. Impressive looking people in suits. You could almost see the money steaming off those impressive suits. It was…impressive. I looked away to the Pacific again. Also impressive…but not as unsettlingly stirring as that money moving through corridors, directed by an enticing, directing will.

I struggled to get ahold of myself. I breathed deeply, causing the smooth, luxurious skin of my cleavage to rise enticingly — though, of course, I was completely unaware of my own considerable personal beauty. Would Sebastian Mauve be unaware as well? Did I want him to be? I was here on professional business — to interview the wealthy mystery man whose incredible power, wealth, and mystery probed into every rarefied orifice of finance. He was…mysterious. And it was up to me, Alisa Irons, reporter for the spunky internet startup Power and Money, to plumb that mystery.

Or, suggested my traitorous inner lady bits with an involuntary flutter, to be plumbed by it.

The elevator slid to an immaculate stop redolent of good taste, and the doors hissed open. I gasped, once more unconsciously agitating my bosom, as I beheld the massive antechamber beyond. Holy crap. The décor was sumptuous and subtle…but also, subtly, disturbing. The thick carpet was covered with swirls and patterns, almost seeming to form a script or an alphabet throbbing with unspeakable meanings. Directly in front of the elevator was a pedestal, upon which a nude bronze sculpture of a shockingly well-formed and realistic woman (somewhat resembling myself!) struggled with what looked like an octopus. I looked closer, and realized it was not exactly an octopus — there were too many tentacles, and the central head was not really a head, but itself a mass of writhing limbs. My broad reading led me to conclude, therefore that it was some sort of mythological thingee. Not an octopus, anyway. Also it was not struggling with the woman, but…holy crap. I turned my eyes modestly away to the wall hangings, which were also covered with swirls, swirls, swirly swirls. They dipped and slid and criss-crossed not unlike those not-octopus limbs. They coiled around and up, sliding smoothly into my eager, pouting brain the way they slid right up into the statue’s….

“Miss Irons?”

I started. Oh, my. I was looking into the eyes of a very beautiful woman. Her dark eyes were limpid pools, her white bosom strained against the fabric of her blue dress. Around her neck was an odd piece of jewelry…a kind of octopus, but not really an octopus, like the one on the statue. Its tentacles seemed to be exploring her cleavage, which was more amply visible than I would usually expect in a business setting. But perhaps cleavage amply displayed was what Sebastian Mauve demanded. I imagined Sebastian Mauve perusing the cleavage. My inner lady bits sat up and did some complicated writhing at the thought. What sort of man was he, who would so boldly, so shamelessly, peruse both staff cleavage and octopus statue rape? Skeevy, perhaps. But it was the skeeviness of power.

“Yes,” I breathed, perhaps too enthusiastically. “I’m Alisa Irons.”

The woman looked me up and down frankly. “I’m Virginia, Sebastian Mauve’s personal assistant. Come right this way, please.” She turned briskly, whisking the cleavage away, and replacing it with a stellar bottom. Oh my. I felt a flash of some indefinable emotion as I thought of Sebastian Mauve’s relationship with that roundness. Had he watched it swivel above this very carpet with these very oddly affecting swirls? The speculation and the gyrations and the contemplation were all making me feel a little dizzy.

And then the door was open, and he turned and holy crap. His eyes smouldered; his tailored suit hung just so on his well-muscled frame, his pants hung just so on his, oh my.

“Hello, Miss Irons,” he said, his voice cultured and bristling manfully with manliness.

“Hello,” I said vaguely. Everything tilted, and I pitched forward helplessly. Two of the three grapes I had eaten for lunch came rushing up, and out.

He had caught me. His eyes smouldered into mine. An ironic smile played over his lips. His mouth opened enticingly.

“You vomited on my jacket,” he said, wittily.

“I know,” I volleyed back.

“It takes a strong woman to have the courage to vomit on the jacket of a man as quietly powerful as I am,” he volleyed back back. I could smell his scent — aftershave and cleanliness, with just a hint of brine. My inner lady bits did back flips. The lone remaining grape in my intestine told them testily to stop it.

Sebastian smiled smoulderingly, as if he could see my thoughts, and the thoughts of the lady bits, and also perhaps of the grape. “Ostentatious incapacity intrigues me, Miss Irons,” he said. “It speaks to an unusual truthiness of character.” With a single motion, he settled me in a sumptuous chair and tore his shirt asunder. Buttons popped off, abs popped out. His chest was smooth and chiseled. I bit my lip. He tossed the shirt into a corner with a casual abruptness. Oh my.

He leaned towards me, smouldering black eyes smouldering, muscles tensed across his bare arms. “Are you…feeling better?” he said, with a low intensity that ensured a final, decisive route of remaining grape by ladybits.

Before I could answer, his cell phone rang. The ringtone was something classical and impressive, showing his refinement and taste, as classical music will. Though I did not recognize it, I responded intuitively and with all my heart and refinement and taste.

“How beautiful!” I said, as the tinny phrase repeated.

I saw his eyes open wider as he realized we shared a common love for whatever his ringtone was. It was a bond that would never be broken.

He answered the phone decisively, our eyes still locked. Then his jaw clenched and he turned away. I watched the muscles of his back as he uttered brief, staccato commands and answers. He was probably moving almost unimaginable amounts of money with every monosyllable. The back muscles moved, the commands staccatoed, the money whizzed. I didn’t care about material things at all — if I did, how could I have responded so forcefully to the spiritual beauty of the ringtone? Still, watching him command money and stuff with his shirt off was pretty hot.

He slammed the phone shut. He turned back to me. His dark eyes were full of anger…but when he spoke it was with a surprising gentleness.

“Miss Irons,” he said quietly. “Are you a virgin?”

I caught my breath. I bit my lip. I flushed. My inner ladybits cheered. The grape was so stunned it shriveled to a raisin.

“That is none of your business,” I said. “How dare you? I…I am not merely a sum of money you can move about on the phone, no matter how sexily.”

He crossed his arms on his magnificent chest. “Please,” he said. “I know we are all sensitive people, and that we have so much to give. But this is an emergency. Your safety is in peril.” He came around the desk. I caught my breath. My bosom heaved without my knowing it. “Your hymen,” he said. “I need to know its status. Now.”

Something in his tone, something in his assurances, assured me. “Yes. I…I’m a virgin,” I admitted. “My hymen is intact.” I lowered my eyes. “It’s probably because I am so unconscious of my extreme beauty that things have come to this pass,” I said apologetically.

His jaw, which I was sure had tightened as much as it was possible for a jaw to tighten, tightened further. “I would curse your demure and improbable lack of self-knowledge,” he said, “if it were not so endearing. And even then, perhaps, if we had time. But we’ve got to get you out of here!”

He grabbed me roughly and lifted me from the chair, propelling me towards the door with strong, strong, knowing hands.

“Mr. Mauve,” I said. “What…?”

We stepped through the office door and my half-formed thought choked and died and ceased to form.

Virginia was braced against her desk, her arms rigid. Her skirt was hiked up around her waist. Her spectacular ass bucked and thrust rhythmically, in time to the thrusts of…oh my.

It was man-like, to some degree. Two arms, two legs. At first I thought it was a guy in a costume, which clearly would not have been appropriate for the office, anyway, but still. After a couple seconds, though, I saw the proportions were not quite right. It looked sort of like that black lagoon creature; it was obviously aquatic. Its webbed, green-black hands were wrapped around her hips; the frills at its neck quivered in eagerness or satisfaction or anger, or just to quiver, who knew? Though a virgin, I was not utterly without experience, and so I could tell that its penis was thoroughly unlikely, if not actually impossible. It was green and huge, with ribs all down the side, and some sort of twist or hook at the end. It didn’t look like there was any way it could go in, despite Virginia’s obvious and extreme lubrication. But in it went. Holy crap.

Virginia screamed.

The creature, apparently encouraged, thrust again. Its tongue, a long ropy strand, came out of its toothy mouth and dexterously performed an evaluation of Virginia’s interior assets in preparation for a sensitive merger. She screamed again. The creature made a wet growl.

I felt shock, and horror, and a confused but intense communication from the inner lady things. But all those emotions were overwhelmed by pity. I put my hand on Sebastian’s bare shoulder as he pulled me across the room.

“This…this sort of thing happening in your lobby,” I whispered. “Mr. Mauve — Sebastian — I never guessed. How it must hurt you!”

He turned his dark eyes to me. They still smouldered, but in a vulnerable, wounded way.

“You look like my mother,” he said. “Here, now…with all this….the giant ribbed penis…the anal tongue sex….”

He tried to go on, but I shook my head, touched that this tragic moment of fish-sex which we had lived through together had uncovered in him unexpected depths. “No,” I said. “You don’t need to say anything else. I understand.”

I knew the moment was real. My inner lady bits, the grape, me myself — we were all in agreement. Even the fish-thing seemed to recognize the importance of what we had; it pulled out of Virginia’s various apertures, and turned towards us. Some viscous, greenish fluid was dripping from it where it was difficult to ignore. Virginia sat up too, her tits declaring her an independent woman who could make her own decisions about fish sex. Also, she made a little noise as the fish creature stepped away from her, towards us. Its thing quivered. Oh my.

Sebastian grabbed me and jammed me into the open elevator. The doors closed just in time. We were safe.

Or…I thought I was safe. Until I turned to Sebastian.

“You!” he said. “What do you think you were doing!”

Though I felt that after the ringtone and the fish-sex in the lobby I knew him better than anyone else did, or could, still his character was more complex than many other complex things, and this was obviously one of those complexities. I cast about helplessly, trying to imagine what I had done to offend. “You mean…coming here while virgin?” I asked tentatively.

“Hah!” he said. He loomed over me, his smouldery eyes flashing and smouldering. “A virgin! Are you telling me you were not looking at that giant green penis?”

I flushed, and bit my lip for good measure. “It was right there,” I said. “I could hardly have helped looking at it…and besides!” I rallied, “I bet you were looking at Virginia’s huge tits, weren’t you?”

He seemed taken aback…then grinned. “Don’t you know that no man is going to look at anyone else’s tits when you’re in the room?” he said.

“No,” I said, “I don’t know because I am completely unconscious of my own personal…” I didn’t get any more out. He had taken me in his arms; the clean scent, with a hint of brine, was all around me as his lips pressed against me. I could feel his erection hard and unashamed. It did not feel as big as the fish-man penis, but it was plenty big enough.

He pushed me up against the elevator wall that I couldn’t help realizing that he owned. It was like being kissed on the front by him and on the back by his stuff, which was almost more him than him since there was more of it. His tongue moved skillfully, his stuff was hard… oh my.

Outside the glass walls of the elevator was a scene of excessive debauchery. Fish-men-things, like money, were everywhere…and, it seemed, in everyone, of whatever gender. As we descended one level, I saw a well-preserved women in her 60s joining a young blonde in performing enthusiastic fellatio on one of those ribbed monstrosities; on another, a well-endowed man was stroking himself while the creature entered him from behind. I could even see a few of the things climbing the outer walls, their erections dragging against the windows, leaving little trails of cum, or slime, or whatever it was.

As a lover of great literature from Pride and Prejudice to Twilight to 50 Shades of Goo:Bred by the Billionaire Tentacle (available as a digital e-book), I sensed that there were narrative complications that had not yet been fully explained.

“Sebastian,” I said determinedly as he bit my nipple in passing, and kept moving down. “Sebastian…oh my! Sebastian…ooooh…if you are not careful, I am going to orgasm while watching a giant green penis sodomize one of your colleagues!”

Sebastian’s ministrations stopped abruptly. His face appeared, his mouth somewhat damp, his brow furrowed, his dark eyes doing that thing they did. Which was smouldering.

“What?” he said.

“You heard my independent and spunky repartee,” I said firmly. “Green penises. Wit!”

Sebastian looked around. I could see the heavy burden of having his office sacked by fish sex monsters descend upon him.

“Sebastian,” I said. “Tell me. Virginity. Abominations from the deep. Mauve enterprises. Your mother and the wounded little boy inside you. Explain it all, darling. I won’t judge you.” I reached out to smooth his face, but missed and grabbed his impressive erection instead. He seemed to find it comforting, so I left my hand there. He gazed into my eyes, pumping subtly below the waist.

“You are an extraordinary woman, Anna,” he breathed. “Despite everything, I’m glad you fell into my office and vomited copiously on my shoulder.”

“My name’s Alisa,” I said, tracing lightly up his shaft.

“Right,” he agreed. The elevator doors slid open. The corridor outside seemed fish monster free. He grabbed my arm and pulled me swiftly after him.

“I will tell you everything, Alisa,” he said. “You deserve that much. But first we need to make sure you’re safe.” He flipped his cell phone open with a masterful air of command. “Alfred,” he said. “The Batcopter!”

Holy crap.

_____

“So,” I said. “You’re Batman.”

Sebastian nodded distractedly, still distractingly shirtless, as a trusty minion piloted the famous crime-fighting copter out over the Pacific.

“It’s a way of giving back,” he said. “When you make your billions as quickly and obscurely as I did, you feel, of course, entirely justified in your own improbable brilliance, but also grateful to the average schmucks who got out of the way. The least you can do, really, is don a costume a few nights a week to become a dark avenger of crime. ” He shrugged. “The adrenalin rush is fun, too. Nice change of pace from the other extreme sports I’ve tried, like cliff diving, prole tossing….” He trailed off. “But that isn’t what you want to talk about, is it, Arabella?”

“Alisa.”

“Right.”

His eyes brooded.

I wanted to brush the hair from his eyes. I missed again and stroked him down there. He made a cute little sound. Oh my.

“Your mother,” I breathed. “Fish sex invasion. Virginity. Why?”

He nodded, once; the crisp, harsh nod that struck fear in the cowardly hearts of criminals and sent funds scurrying like green fish with penises through the glistening tubes of extreme philanthropy.

“My mother was a whore,” he said, raising his eyes to my face. “She looked just like you.”

My heart melted. His member twitched at the profound sorrow of his words. I jerked gently, knowing that what he needed now, more than ever, was tenderness.

“She was on drugs,” he continued, as I slid down to better facilitate the truth rising in his wounded manliness, like truth sap in a truth tree. “And she was also involved in obscene and unspeakable rites. She summoned things from outside of time; horrible twisted abominations that should not have been! Can you imagine what it was like, Alexandra, to lie there every night beside her, terrified, and watch the tentacled beasts crawl up through the rotten boards of our decayed hovel to satisfy their depraved lusts?”

I shook my head in horror, running my tongue back and forth across the hard knot of his shattered youth, which was extremely hard. I fondled the backstory lightly with my fingers. Holy crap, and also oh my. This was incredibly hot — and also, no doubt, therapeutic, especially since I reminded him of his mom.

“Let it all out,” I said, but my mouth was full so it came out as “Lepphalt.” An appreciative throb assured me that he understood the sentiment.

“She would step naked into the bathtub,” he continued, his voice rising. I was concerned for a moment, but then I figured the minion had heard it all before. “Her firm white breasts rising in anticipation, the exploitive Oedipal content hard and red with depraved lust. The thing that waited rose up, its head a writhing mass, its long tentacles thrashing.”

He touched my head as I bobbed, and his voice took on new urgency.

“That’s…uhh..that’s why I…want you to let me sacrifice you to Cthulhu. It’s what I do with all my girlfriends. I…oh…find someone who looks just like Mommy, seduce her, and then throw her to the unspeakable eldritch fiend so it can rut in all her orifices and drive her utterly mad! Oh!” he exclaimed in a final spasm of sincere vulnerability and also semen. I looked up thoughtfully, watching his sexy concerns detumesce. I was glad to have helped him so much…but could I possibly help him so much more?

“So,” I said, biting my lip in a manner which was unconsciously fetching, “you want to watch me be violated by a hideous atrocity from outside of time and space?”

“Yes,” he said.

“And this is what you do with all your girlfriends? This is what it means to have a relationship with you?”

“Yes,” he said again, with a hint of impatience.

“And…the virginity? The fish-sex invasion?”

He shrugged. “Cthulhu likes virgins. Private elder god reasons. And the fish monsters come every Thursday. It’s a team building exercise.”

“It’s Wednesday.” I pointed out.

He nodded. “Right.”

I sat back on my haunches, which were so similar to Sebastian’s mother’s haunches, and which, therefore, Sebastian found appealing even outside of their innate attractiveness. I basked in the aura of Sebastian; the custom crime-fighting helicopter, the silent minion up front who had seen so much and was yet so cheerfully bland and faceless, the shirtlessness, the flaccid but stimulating penis. Did I want to be sacrificed to an unnameable horror? My inner lady bits were perhaps somewhat interested; Sebastian’s description of his mother’s ravishment was certainly impassioned. On the other hand, my grape pointed out that there was maybe something mildly disturbing about Sebastian’s intense dedication to his noble war on crime. And what about all those other girls?

“Did you throw Virginia and her big tits to Cthulhu?” I asked him.

He snorted. “Virginia! She looks nothing like my mother! Besides, do you know how hard it is to find a good secretary? Those who Cthulhu uses are shattered in body and mind and their souls devoured. You can’t take good dictation after your soul is devoured. Even filing suffers.” He stood up, his penis dangling, his biceps bicepping. He clasped me tightly against him. “Andrea, I don’t just throw every attractive, bosomy girl I come across to my unholy master. Only the truly special may be meat puppets for Cthulhu. And you…you are the most special meat puppet I have ever encountered!”

He looked at me with those dark Sebastian eyes that had looked at so many possessions, so much money, so many bosoms, and so many tentacles. I felt my inner value skyrocket as I realized all the luxury items that he was ignoring, all the other things he could consume to salve his trauma rather than utterly destroying me in a bizarre sex ritual. Yet it was the utter destruction that he wanted; the utter destruction he needed. How could I not feel flattered? How could I not feel safe as he lifted me in his arms and flung me, despite my screams and protests, out of the helicopter and into the Pacific far below?

“Afterwards I’ll buy you a Volvo!” he shouted in parting.

The wind whipped about me as I fell, Sebastian’s wounded expression of anticipation and his again-rigid consumption pattern receding above me, the unique, incredibly expensive Bat-copter piloted by the well-paid minion falling away. The wind howled, but that was quickly drowned in the mighty roar from below. I caught a glimpse of Cyclopean tendrils falling from unnameable perspectives, and then the terrible maw engulfed me, and my dress was torn away like one of those things that gets torn off in one of the many, many novels I have read about tearing. I imagined Sebastian looking at me through very expensive Bat-binoculars, made just for the viewing of distant tentacle-rape, and felt the grape retreat in a huff as my inner lady bits moistened. Oh my.

The smell of brine was everywhere, reminding me of Sebastian’s scent. For an inhuman unspeakable demon, it was remarkably gentle, as if it was instinctively tamed by the curve of my thighs and my appreciation of the Impressionists and designer watches. Delicate, independently writhing cilia played across my incessant self-questioning. Was it right to accept a Volvo? I tried to call Sebastian’s name, but all that came out was ” ph’nglui mglw’nafh Cthulhu R’lyeh wgah’nagl fhtagn.” Perhaps this sort of translation problem was why Sebastian had had such problems with former sacrifices and dictation.

I saw the great tentacle rise before me, huge, grey-green, and ribbed, like a gigantic version of the fish-men penises that Sebastian had not wanted me to look at. A giant lidless eye opened, the swirling geometries causing me to drool and gibber, even as I understood intuitively that it had its own sorrows, and its own tragic reasons for manifesting as a monstrosity whose foul, slimy, hideous and mountainous flesh concealed a heart desperately in need of love. It stroked various things leisurely, then moved down, down, down…and suddenly thrust. Holy crap.