This first appeared on Splice Today way back when. It seemed like a nice piece to run for the 4th. Who’s America if not Chuck Berry?

______________________

Blues and folk musicians soldier on forever, keeping the tradition alive. Rock musicians soldier on forever, turning into lumbering saurian parodies of themselves. Somewhere in the middle are rock and rollers, whose latter-day work is neither exactly respected nor exactly despised. Rather, for the most part, it’s just ignored.

Blues and folk musicians soldier on forever, keeping the tradition alive. Rock musicians soldier on forever, turning into lumbering saurian parodies of themselves. Somewhere in the middle are rock and rollers, whose latter-day work is neither exactly respected nor exactly despised. Rather, for the most part, it’s just ignored.

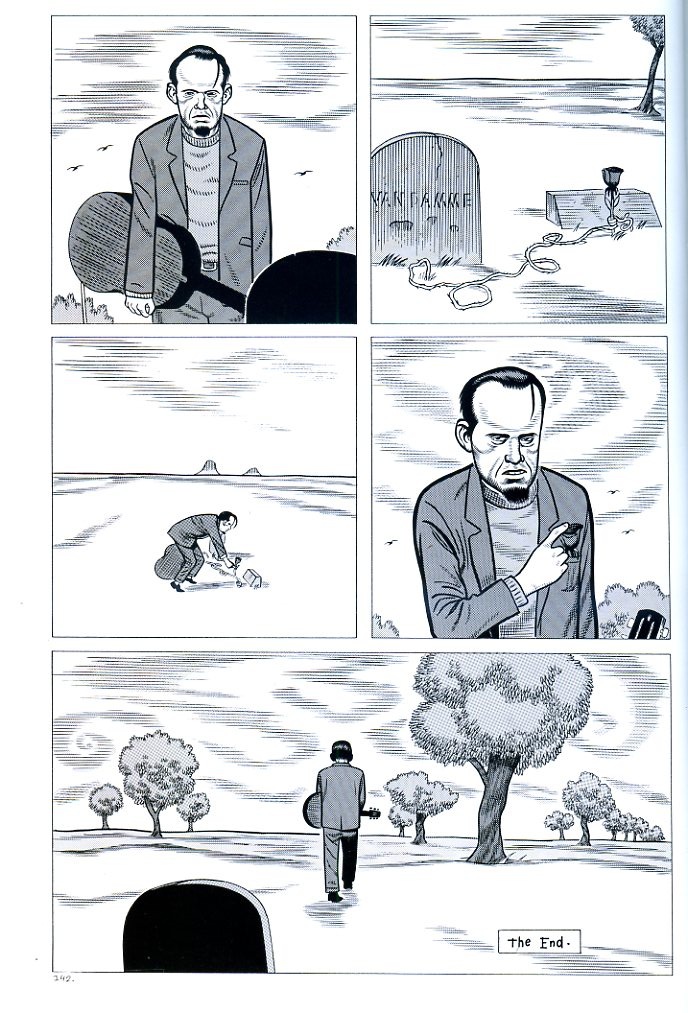

Which is why it’s so weird to realize that, unlike Elvis or Buddy Holly or Johnny Cash or Sam Cooke, Chuck Berry is still alive and still touring. He hasn’t recorded a studio album in more than 30 years, and hasn’t even had a live album in 8, but at 84 years old and counting, he still goes out there playing the same half-century old hits. Not a tradition or a parody, he’s no longer got a mass audience, exactly, but he’s still what he always was: Chuck Berry, performer.

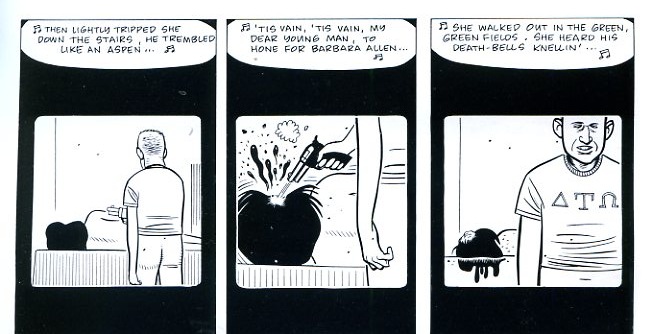

It’s maybe fitting, then, that Berry’s last great artistic effort wasn’t a hit but a personal testament. His 1987 autobiography was, according to the man himself, “raw in form, rare in feat, but real in fact. No ghost but no guilt or gimmicks, just me,” and you can hear the truth in the rock of the phrase and the roll of the alliteration. Berry says he’s only read six hardbacks in his life, and that the dozens of paperbacks he’s paged through were “only for the stimulation”. Yet his love of language comes through on every page. Open at random and you find:

“Opportunity and temptation were anywhere you let them be. New ideas, ideals, and eye dolls were there to be held.”

“We were ‘short hairs and busted’ […] and were told if we wantd to kick back our ‘dime,’ we’d have to keep our mind off the streets, our hands off ‘ourselves,’ drink plenty of cool water, and walk slow.”

“Nine handsome young southern gentlemen were lined beneath the wing of the DC 3, elegantly welcoming me to Mississippi. I felt like the stately son of Stonewall Jackson, but it lasted only four minutes.”

There’s no doubt about it; that’s the same man whose lyrics included motorvatin’, coffee-colored cadillacs, and bobby soxers wiggling like whimsical fish.

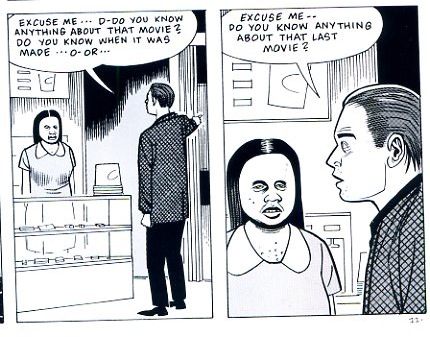

While the voice is unmistakably Berry’s, though, it wouldn’t be quite right to say that the lack of a ghostwriter makes the book more honest. Even in the 3 minute medium of rock and roll songs, Berry’s quick wit tended to undercut a surface directness with a sly ambiguity. Those bobby soxers wiggling like whimsical fish — is Berry admiring them? Making fun of them? Lusting after them? The brown-eyed handsome man doesn’t just have brown eyes, surely; and why did Marie’s mom tear up that happy home in Memphis, TN anyway? Performers like Little Richard or Bo Diddley had lyrics which were exuberantly clever, but Berry was perhaps unique among the early rock and rollers in how he used words to dance around what he had to say. In the autobiography he notes that he rarely used songs to express love…but the broader truth is that, unlike almost all his peers, he rarely used songs to express any direct emotion. In a music pitched in some sense at kids, he always maintained a very adult distance.

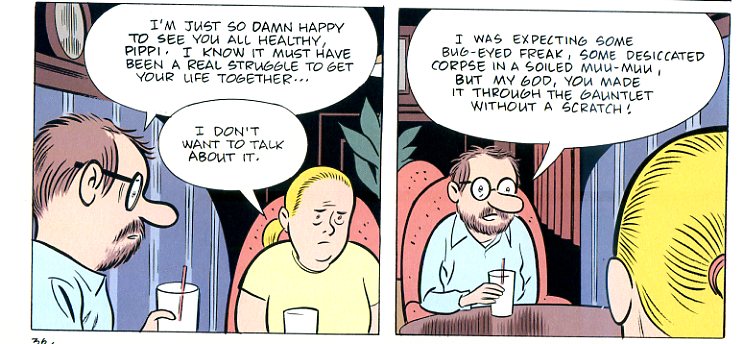

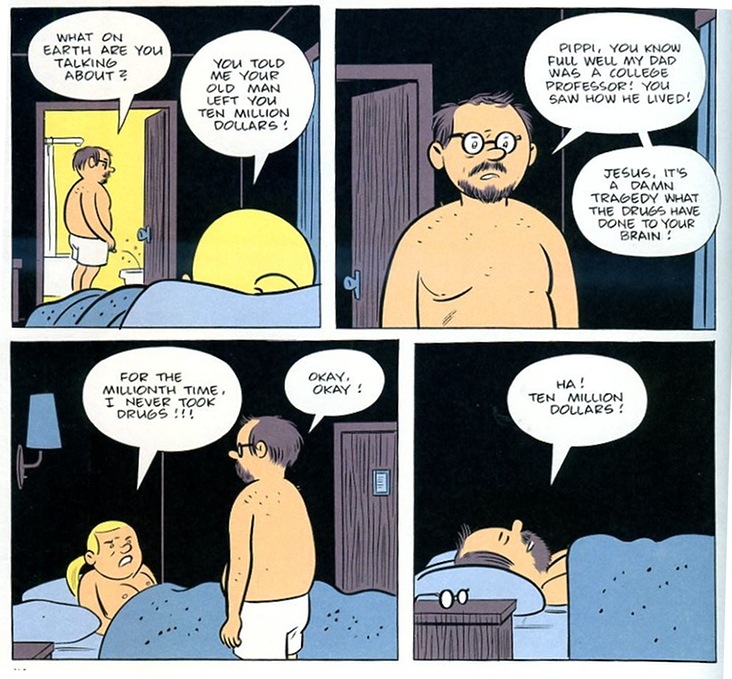

The adultness and the distance are both fully visible in the autobiography. Berry can be remarkably frank; the book sometimes reads like a meticulous chronicle of every time he ever had an erection. Fellatio, cunnilingus, lesbianism, and condom use all make an appearance with just enough dissemblance to keep the book from out and out porn. He also talks openly about his fascination with white woman, discussing his obsession as a young boy with a white nurse and noting, “My mother’s nurse had a profound effect on the state of my fantasies and settled into the nature of my libido. I’ll tell you more later.”

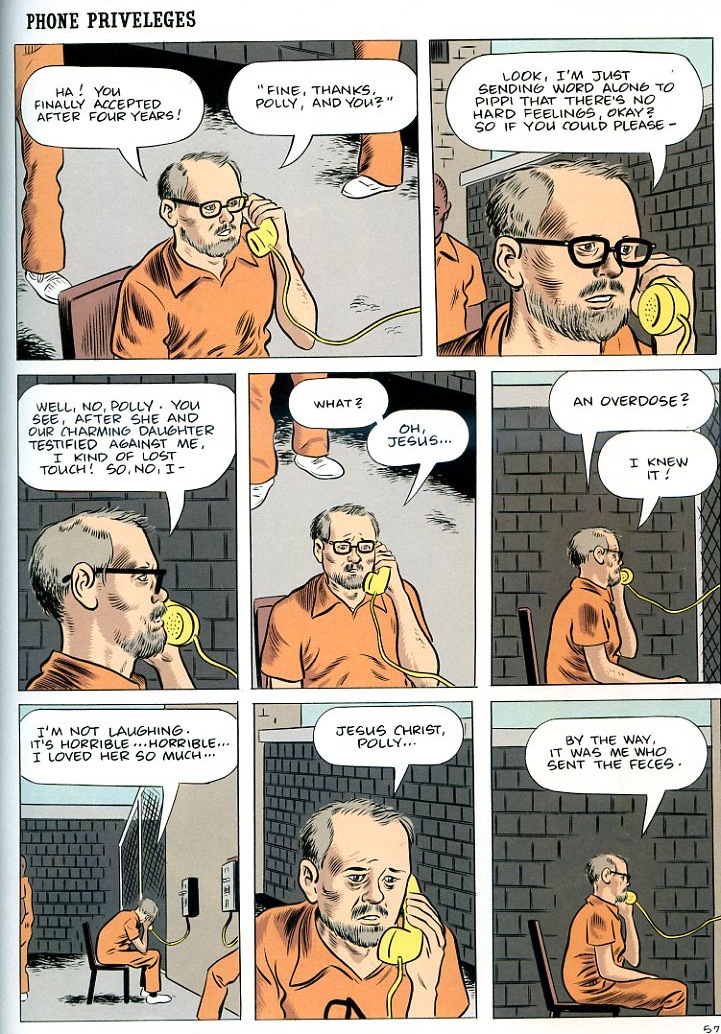

And he does tell more later…sort of. There are numerous stories of sexual encounters with white women, from millionaires to hippies to prostitutes to French reporters. But how his philandering affected his relationship with his long suffering wife, or even his own emotional life, is skimmed over. His most important relationship with a white woman, his longtime association with his secretary Francine, is given a separate chapter which seems designed to hint at everything and confirm nothing. Berry actually includes a large section written by Francine, in which she praises him in phrases that sure sound like the endearments of a lover. But Berry never admits to sleeping with her, and certainly never lets slip what his wife thought about her husband and his devoted secretary jetting off to tropical vacations together while she stayed home to mind the kids. Nor do we learn how his relationships with either his wife or his secretary was affected by his abortive sexual dalliance with a 14-year old — a dalliance which he insists was never consummated, but which nonetheless landed him in prison on dubious-but-not-nearly-dubious-enough charges under the Mann act.

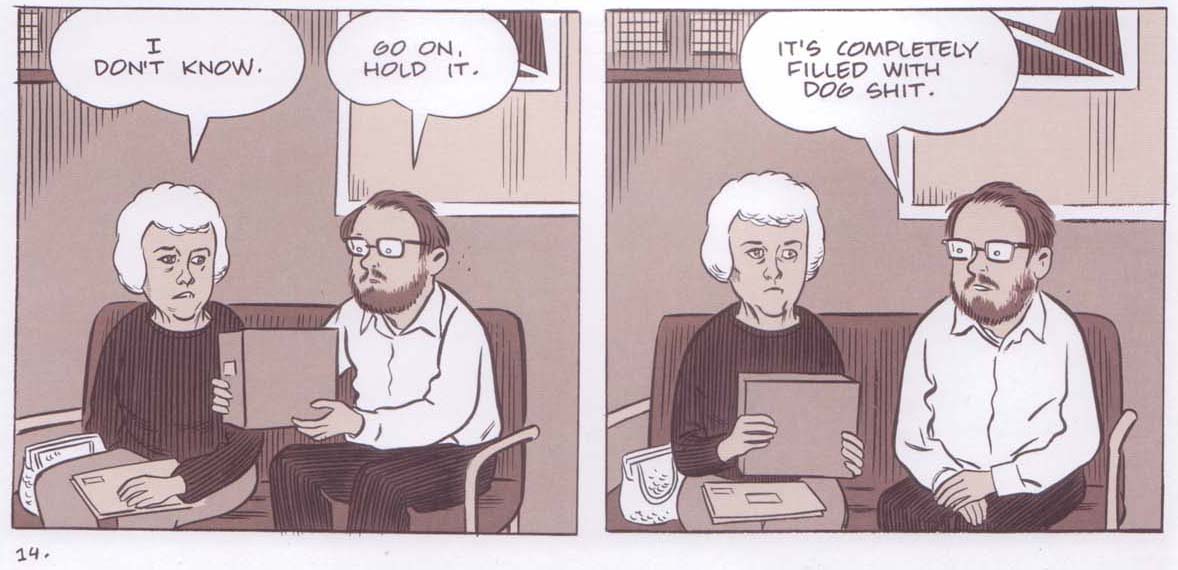

So it goes with most of the major themes of the book. Racism shadows his childhood, his relationships with white women, and his performing career, but it’s place in his psyche is more alluded to (as a source of fear or triumph or irritation) than elucidated. His consuming obsession with money is evident throughout, culminating in tax fraud committed, he says, because he wanted to get his bank balance to $1 million — but the closest he gets to actually explaining his attitude to his fortune are a few pithy, clearly misleading phrases about how he would play even if there were no profit in it. As for his songwriting, as Robert Christgau notes in an old review of the autobiography: “you get a funny feeling from this book: either music comes so naturally to the man that he gives it nary a thought, or he just plain gives it nary a thought.” (http://www.robertchristgau.com/xg/bkrev/berry-87.php)

It’s possible Berry doesn’t think about music — or possible, anyway, that he hasn’t thought about it in a long time. His style was set fairly early on, and while he mentions the Beatles and the Stones and some others, it’s clear he admires them, to the extent he does, for their fame and professional accomplishments, not because he cares a lick for their music. It’s the performers he heard in his youth — Muddy Waters to Nat King Cole — that he’s passionate about. If he was inspired by any musician after 1960 or so, you sure can’t tell it from this book.

Indeed, and as is the case for many celebrity bios, the material here about his childhood is the most vivid and the most powerful, from his joyful memories of squabbling over the piano with his siblings, to the queasy discussion of being forced to kiss the feet of a white woman on a golf course, to the even queasier account of a disastrous road trip turned hapless crime spree which landed him in juvenile detention on a ten year sentence. In this early section, you can see the connections between libido, race, music, ambition, and language which created a performer eager and able to conquer the world.

In adulthood, those connections get blurry — rubbed out, finessed, erased. A ghost writer might have gotten Berry to tell more, or at least to more directly refuse to talk about the stuff he doesn’t want to talk about. But if there’s not necessarily an honesty in the telling, there’s at least an honesty in the obfuscation. Berry’s about what he won’t tell you as much as about what he will. So when he goes out on stage and repeats the lyrics he wrote decades ago, you have to feel it’s not because he’s slacking off, but because he figures he already said what he had to say.