Ta-Nehisi Coates’ run on Black Panther has been the most anticipated comics event in at least a decade. Coates is known far beyond the tiny world of comicdom; he’s a bona fide literary celebrity, of the sort that writes comics only very rarely. I’m hard-pressed to think of a writer of equal stature who has come up outside comics and entered the field. Neil Gaiman, who started in comics and left when he got big enough, is the counter-example that proves the rule.

On top of that, Coates is a black writer, entering comics at a time when there have been increasing calls for more representation of POC and women in both Marvel’s film properties and the comics themselves. By putting Coates and Brian Stelfreeze on Black Panther, Marvel is directly addressing its own often monochromatic history.

Black Panther, then, promises to be a new kind of flagship Marvel title—different in quality, different in publicity, different in importance, different in its thoughtfulness about, and approach to, issues of race. It’s an exciting promise—and issues were leaping off the rack like hotcakes at my own little comics shop on Chicago’s South Side.

So—many hopes. Were any of them met?

The answer to that is: no. Black Panther #1 is, unfortunately, not a good comic.

It’s not a terrible comic, either; I’ve read plenty worse. It’s simply a mediocre Marvel comic in the usual mediocre Marvel comic ways.

The main weakness, as ever, is continuity porn. The issue starts with a page of exposition detailing several previous preposterous storylines: there was some stupid plot by Dr. Doom; there was some other stupid plot by Thanos. But even that exposition dump isn’t sufficient; much of the rest of the comic paddles around haplessly in convoluted, tedious backstory. We learn about Black Panther’s female bodyguards, there are flashback dream sequences, there’s Black Panther moping around and brooding. There are some brief glimpses of potentially interesting characters, including two lesbian bodyguards who stage a jail break. But there isn’t enough development to make them, or anyone, engaging.

The hope is that after the first issue we’ll get up to speed. But this is a new introduction to the character for a, by comics standards, gigantic new readership. The failure to recognize the need for a streamlined story, and the inability to provide one, is ominous. You’ve got the biggest comic event in years; comics reboot every 15 months anyway. Why not just forget Thanos and Doom and whatever and let Coates, and all those new comics readers he’s attracted, start from scratch? This isn’t rocket science; it’s basic common sense. The fact that nobody involved in the project realized that this was the way to go doesn’t fill one with confidence.

There are other unsettling signs as well. Coates’ nonfiction style is heavy, but it’s a heaviness of thought and consideration; you can feel his mind moving deliberately, and that gives the moments of fire more power. That weight doesn’t translate particularly well to the comic book world, though. The story feels portentous and burdened with its own seriousness. The dialogue in particular reads as if the characters are writing essays in a parody of Coates’ style. “Does he even care, Aneka? Did he ever care?” Dora asks. “Does it even matter? Has it ever mattered?” Aneka replies. Do people really talk like that? Have they ever talked like that? Could someone make them stop talking like that?

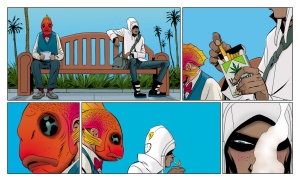

Brian Stelfreeze’s art is…okay. There are certainly lots of worse mainstream artists, but there’s nothing especially distinctive about his style or composition. Action sequences are stiff, and often visually confusing. Again, this is all pretty standard for mainstream superhero comics, which impose both tight deadline pressure and fairly strict limits on artist style. It’s professional. It’s just not anything more than that.

From his other writing, and from the ending letters page column here, it’s clear that Coates is a Marvel comics fan. It shouldn’t really be a surprise, then, that he’s delivered a bog standard Marvel comic, complete with unfocused storytelling, impenetrable continuity, and art that is there. The comic is notable for having a main cast that is entirely black, and for its inclusion of a respectfully treated lesbian couple as primary protagonists. But that’s about the only thing that distinguishes Black Panther from many of its peer titles, at this point. It certainly doesn’t have the distinctive vision of G. Willow Wilson’s YA Ms. Marvel, with its deft, witty characterization, and its exploration of such unusual superhero themes as ethnic assimilation and nonviolence. Nor does it feel as focused and individual as Christopher Priest’s Black Panther run did, from the very beginning.

Maybe Coates and Stelfreeze will find their stride as the series goes on. But there’s an uncomfortable feeling here that they’ve made just exactly the uninspired comic that they, and Marvel, wanted to.