I’m stealing an idea from Thierry Groensteen, from his 2013 book Comics and Narration. After discussing “regular page layout” (pages with rigid panel grids), Groensteen describes “rhetorical layout, where the size (and sometimes the shape) of each frame is adapted to the content, to the subject matter of the panel.” Groensteen then goes on to talk about the relationships of panels to each other, especially “irregular” layouts that have “no basic structure,” but he doesn’t talk much about subject matter. So his “rhetorical” layout may be the same as any “irregular” layout, in which case the term is superfluous.

Except his definition, “the size (and sometimes the shape) of each frame is adapted to the content,” is really useful. But it doesn’t define a type of layout. It defines a type of framing. In fact, it defines all types of framing, since a frame always has some sort of relationship to its subject matter. And this is true whether panels follow a rigid grid or if the layout is irregular, because the rhetoric has to be analyzed one panel at a time.

So let me offer additions to Groensteen’s term.

Framing rhetoric: the size and shape relationships between frame and subject.

Symmetrical framing: the subject and frame are similar shapes.

Symmetrical and proportionate: the subject and frame are similar shapes, and the subject fits inside the frame; because content and frame are balanced in both size and shape, the effect draws no attention to their relationship and so appears neutral.

Symmetrical and expansive: the subject and frame are similar shapes, but the subject matter is smaller than the frame, so the panel includes surrounding content. The effect is spacious.

Symmetrical and abridged: the subject and frame are similar shapes, but the subject is larger, so the frame appears to crop out some of the subject. The effect is cramped, as if the subject has been sized too small.

Symmetrical and broken: the subject and frame are similar shapes, but the subject is larger, with elements of the subject extending beyond the frame. The frame-breaking elements are often in movement or otherwise expressing energy, implying that the subject is more powerful or significant than the frame.

Symmetrical and off-centered: although the subject and frame are similar shapes and the subject appears as if it could fit the frame, the frame appears to crop out some of the subject while also including surrounding content. The effect is of a misaimed camera.

Asymmetrical framing: the subject and the frame are dissimilar shapes.

Asymmetrical and proportionate: although the subject fits inside the frame, because of their dissimilar shapes the panel includes surrounding content.

Asymmetrical and expansive: because the subject is smaller than the frame, the panel includes surrounding content, and because of their dissimilar shapes, the panel also includes additional surrounding content.

Asymmetrical and abridged: the subject is larger than the frame in one dimension, creating the impression of the frame cropping out content, and because of their dissimilar shapes, the panel also includes surrounding content. The effect is an image placed in the wrong shaped panel.

Asymmetrical and broken: the subject is larger than the frame, with elements of the subject extending beyond the frame edge; because of their dissimilar shapes, the frame-breaking elements further emphasize imbalance.

Asymmetrical and off-centered: although the subject appears as if it could fit inside the frame, the frame appears to crop out some of the subject while including some surrounding content; and because of their dissimilar shapes, the panel also includes additional surrounding content. The effect is of a misaimed camera.

Unframed image: an image with no frame. (Duh!)

Secondary frame: surrounding panel frames border an unframed panel.

Implied frame: an unframed image implies a symmetrical and proportionate frame, while usually remaining inside its undrawn borders.

Interpenetrating images: adjacent unframed images and their implied frames overlap.

Secondary frames, implied frames, and interpenetrating images may be analyzed in the same rhetorical relationships of size and shape as framed images.

That’s all really abstract, so check out some examples:

Nick Fury’s body fits inside the full-height column but intrudes into the second column. The unframed panel is symmetrical and broken.

With the exception of the top right close-up, each panel shows Beast’s whole (or nearly whole) body, which is drawn to fill the shape of the panel, and so is symmetrical and proportionate.

Wolverine’s body, however, does not entirely fit; his feet, part of his arm, and the top of his head are cropped. The column panel is symmetrical and abridged.

The top panel is symmetrical and proportionate. The second panel crops the face (part of the lower lip and both eyebrows are missing) but includes a lot of surrounding space. The panel is asymmetrical and abridged, as is the third. The last is symmetrical and proportionate again.

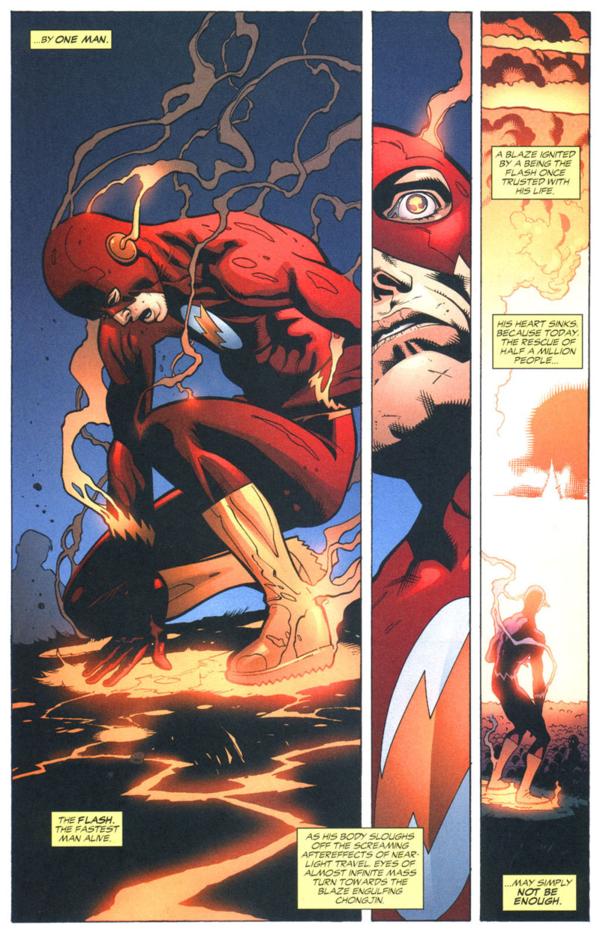

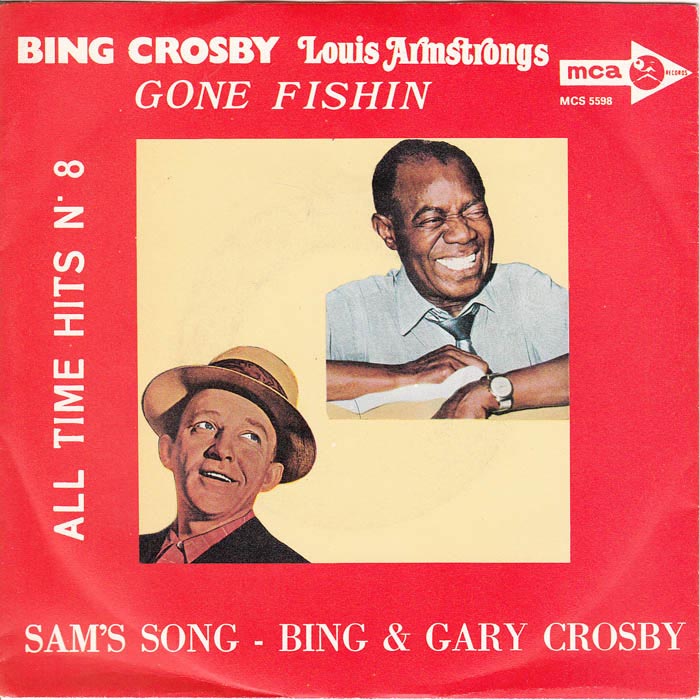

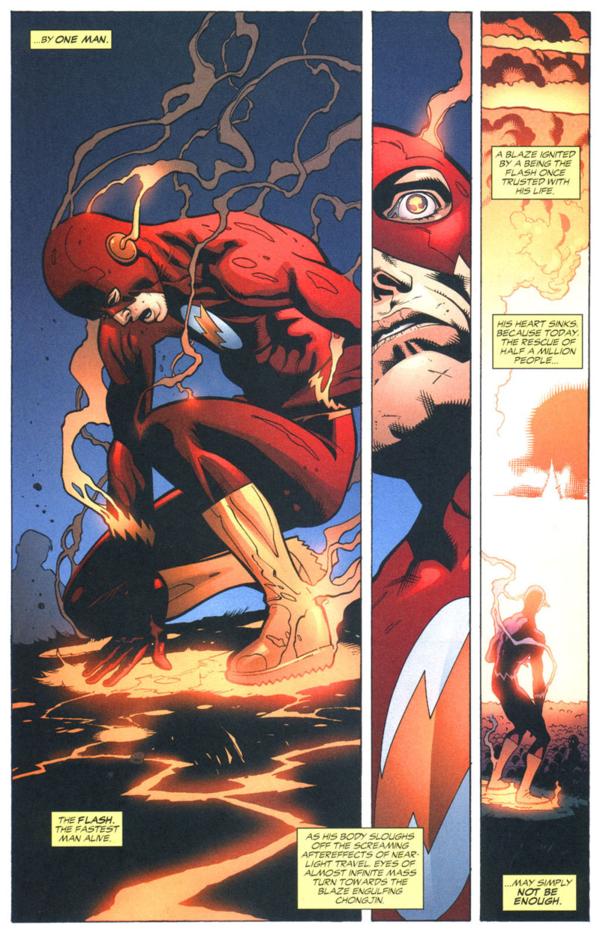

The first panel is asymmetrical and proportionate (or off-centered depending on whether you consider his elbow primary content). The second column is drawn as if too thin to contain all of Flash’s face, so the panel is asymmetrical and abridged. The last is asymmetrical and expansive.

The top panel is asymmetrical and expansive, with detailed elements of the wall in the foreground. The bottom left panel contains Spider-Man, but with ample additional space around the figure, so that non-essential elements of the city landscape are included in the frame. The panel is symmetrical and expansive.

The bottom, page-width panel includes its two primary subjects, Batman and Alfred on the balcony behind him, but the angle and distance includes additional content, including the entire moon, distant buildings, and the wall below the balcony. The panel is symmetrical and expansive.

The second row includes a face with a corner of an eye and mouth cut off. The panel, however, is large enough to include those complete features, but the subject has been drawn off-center to produce the cropping effect. The panel is symmetrical and off-center.

The face in the bottom left panel is cut off at the mouth, even though the subject matter could be drawn higher in the panel to include the entire mouth. The panel is symmetrical and off-centered.

The top right panel content could be composed to include Cyclops’ face, but instead his head is more than half out of frame. The panel is symmetrical and off-centered.

The top panel is wide like the subject matter of the street and so is symmetrical and proportionate. The subject matter of the second frame (the heads of the passenger and the driver visible through the car window) fit the frame, but the frame shape extends to the left to include the reflection of a building in a backseat window, so the panel is asymmetrical and proportionate.

,

,

The width of the second panel of “Avengers Mansion” also includes several distant buildings, the front yard, and fence–elements included as if the wide panel shape requires a view of more than the primary subject of the mansion front. The panel is asymmetrical and proportionate.

Not only is the subject of the Hulk much smaller than the frame, the frame itself is shaped so that it must include more than the subject. The panel is asymmetrical and expansive.

The shape of the full-width panels of the second and third rows extend beyond the subject of the two figures. The panels are asymmetrical and expansive.

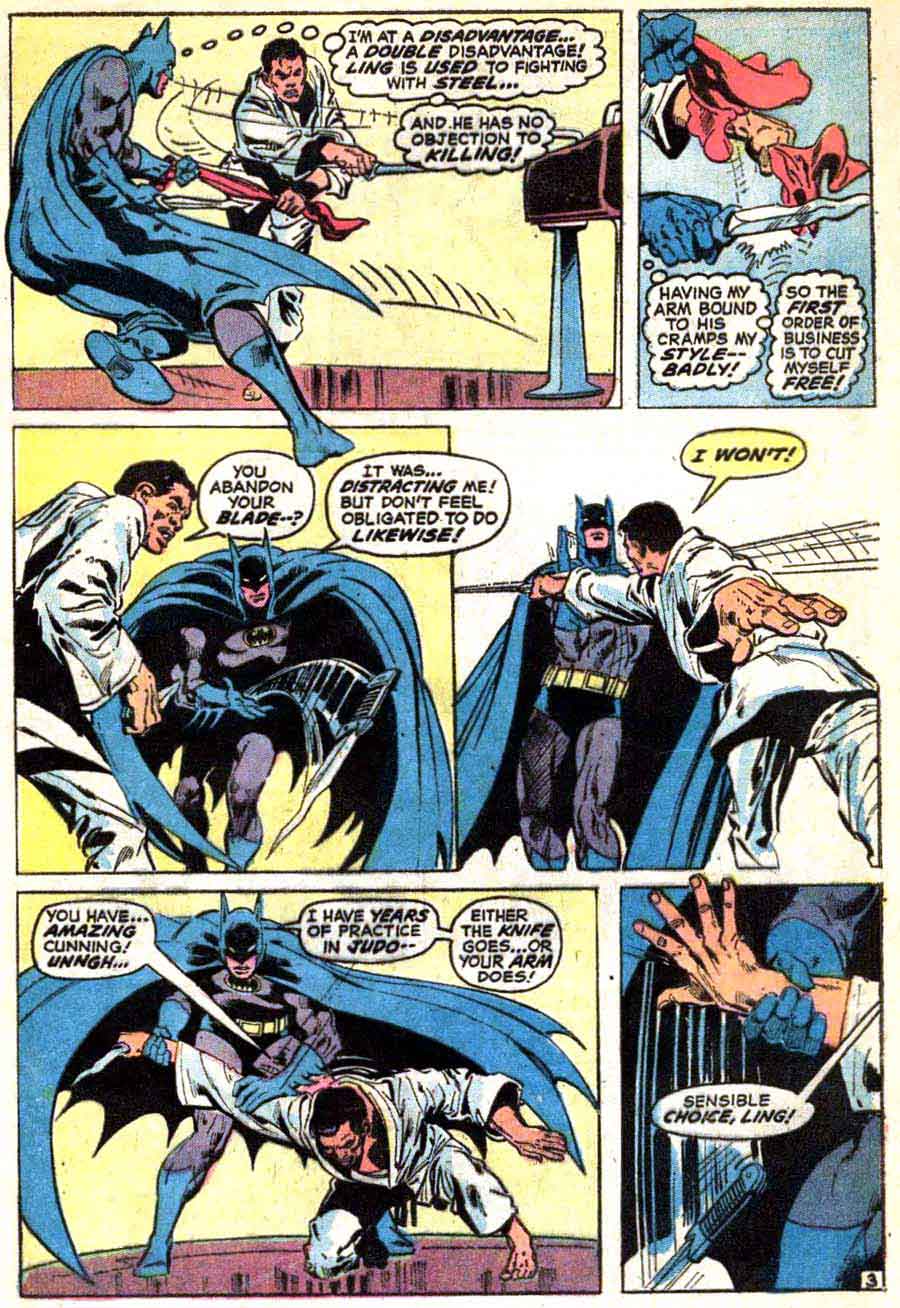

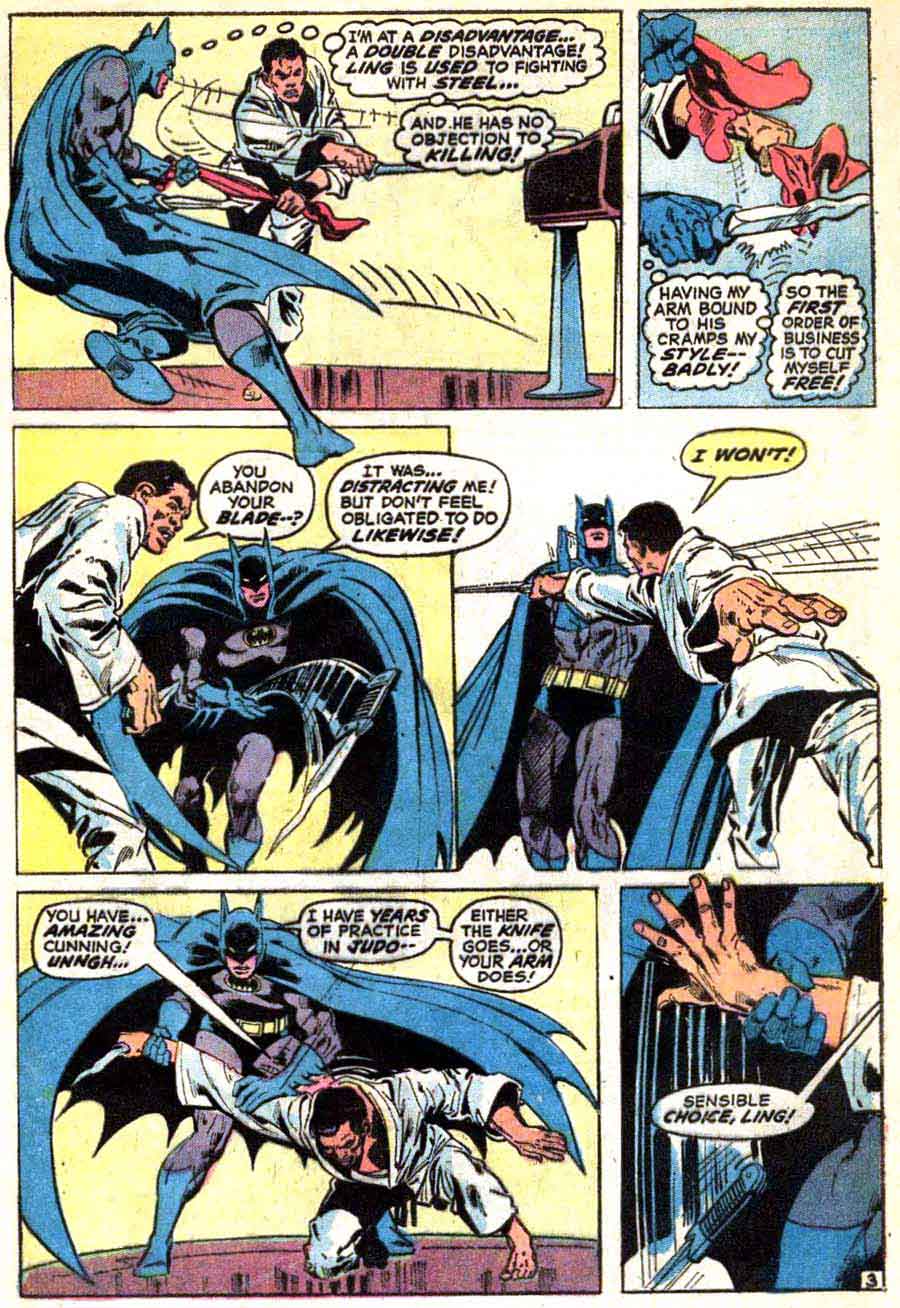

Batman’s leg extends beyond the frame, as if his movement was too fast for the frame to capture. The hand in the final frame also breaks the panel border, again emphasizing action. The panel is asymmetrical and broken.

Every panel of the fight scene but the last is symmetrical and broken. The last is symmetrical and off-centered, cutting off Bucky’s chin while leaving space above his head.

The second row begins with a symmetrical and expansive panel; the second panel is symmetrical and proportionate; and the third symmetrical and abridged. The sequence suggests physical and psychological intensification, but exclusively through framing since the Hulk’s expression remains essentially unchanged.

The first panel of a figure stepping through a door is symmetrical and proportionate. The next symmetrical but expansive panel includes its subject matter (the individuals in the classroom and the classroom itself) but also the darkened top of (presumably) a bookshelf. The spaciousness contrasts the cramped effect of the subsequent panels which are mostly asymmetrical and abridged, except for the second which is symmetrical and abridged.

And, on a last note, I intend to use framing rhetoric instead of film terms for camera distance (close-up, medium shot, etc.), because the film terms don’t account for frame shape (in film the frame shape typically does not change). Also, “camera distance” doesn’t suit a drawn image because there is no camera and so no distance between it and the subject; there’s just the subject and the frame.

,

,