Before meeting Alfred Hitchcock on a train to Hollywood fame, Patricia Highsmith wrote comic books. It was 1942, the height of the Golden Age boom, and a pretty good first job for an English major fresh from commencement. She started at the now largely forgotten Standard Comics but graduated to Timely (AKA Marvel) before leaving the field in 1948—when superheroes were dropping faster than Tom Ripley’s murder victims.

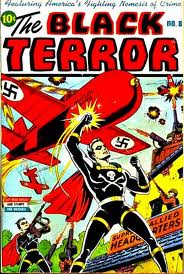

When she published The Talented Mr. Ripley in 1955, the comics market had been bludgeoned to near death by Congress and the Code. She had not been called to testify before the Senate because she had killed off the fact of her first career with a splatter of white-out. Comic books? What comic books? If outed by some sleuth of an interviewer, she might admit to having dabbled with Superman or Batman, but she had probably climbed no higher up the superhero pantheon than the Black Terror, a skull-and-bone chested knock-off since abandoned to public domain.

But for a highbrow author trying to bury her lowbrow past, Ms. Highsmith planted a lot of clues. Tom Ripley’s first victim (of tax scam, the murders come later) is a comic book artist who, Tom therefore assumes, “didn’t know whether he was coming or going.”He even knows that the artist’s “income’s earned on a freelance basis with no withholding tax,” making him an easy mark. Tom’s single real friend, Cleo, doesn’t draw comics, but “painted in a small way—a very small way”; her “imaginary landscapes of a junglelike land” were “no bigger than postage stamps” (like panels in a Thrilling Comics adventure perhaps?). Even Dickie, Tom’s first murder victim, is a painter, albeit a “lousy amateur,” though Tom pictures his pen-and-inks of ships as “precise draftsman’s drawings with every line and bolt and screw labeled.” Tom even takes up a brush himself, imitating Dickie’s mediocre smears.

As far as superpowers, Tom is an old school master-of-disguise. When defrauding that comic book artist, he becomes General Director of the IRS Adjustment Department, drawling “like a genial codger of sixty-odd” years. He wields an eyebrow pencil and a bottle of peroxide wash too, but knows a touch of putty on the end of his nose would be too much. The art of impersonation is a matter of mood and temperament, adopting just the right facial expressions and gait. Besides, he’d always “wanted to be an actor,” and after beating his would-be BFF with a boat oar and stealing his identity, he gets his chance. He even adopts Dickie’s flawed Italian, and of course his signature (“seven out of ten experts in America had said they did not believe the checks were forged”).

Highsmith is a mistress-of-disguise too. Comics were the least of the skulls and bones in her closet. After Hitchcock made her name by adapting her first, 1950 novel, Strangers on a Train, she published The Price of Salt as alter ego Claire Morgan. I’ve not read it, but I think Dr. Wertham and his buddies in the Senate would have cited Ms. Morgan’s sexual proclivities as further evidence of the unwholesomeness of the comics industry. Claire, like her creator, was bisexual, and, worse, dared to end her lesbian romance on a note of hope for her unrepentant protagonists.

Mr. Ripley has the same origin story. He’s stalked by the specter of his own homosexuality, repeatedly labeled “pansy” and “sissy” and “queer.” As a result, he can’t embrace any sexuality. “I can’t make up my mind whether I like men or women,” he jokes, “so I’m thinking of giving them both up.” But where does all that smoldering energy go? Blunt objects. His second murder weapon is an ashtray. The victim is a “selfish, stupid bastard who had sneered at” Dickie, “one of his best friends—just because he suspected him of sexual deviation.” When Tom was alone in a boat for the last time with Dickie (oh, don’t even start on the oar-sized penis jokes), he realized he could have “hit Dickie, sprung on him, or kissed him, or thrown him overboard.” The thwarted sexual impulse is steered into violence. For that tentative reason, I’m not appalled at Ms. Highsmith for ending her crime novel on a note of triumph for her unrepentant protagonist. Like Claire, Tom goes unpunished.

Or at least not legally punished. The damage he commits on himself is deeper. When forced to abandon his socialite existence as the gentlemanly Dickie, he “hated becoming Thomas Ripley again . . . as he would have hated putting on a shabby suit of clothes.” His former self, “Tom Ripley, shy and meek,” becomes just another performance—like the one a certain superpowered alien from Krypton adopts. He decides to “play up Tom a little more . . . He could stoop a little more, he could be shyer than ever, he could even wear horn-rimmed glasses and hold his mouth in an even sadder, droopier manner.” When Highsmith said she wrote Superman and Batman, she meant Clark Kent and Bruce Wayne, the yin and yang of her shapeshifting murder’s Tom and Dickie duality.

Superman and Batman make an appearance too. Yes, Tom fits the standard orphan model (“My parents died when I was very small”), but Highsmith pulls back her superhero mask even further as Tom stands aboard a ship, all but certain he’s finally to be arrested: “He imagined strange things: Mrs. Cartwright’s daughter falling overboard and he jumping after her and saving her. Or fighting through the waters of a ruptured bulkhead to close the breach with his own body. He felt possessed of a preternatural strength and fearlessness.”

In another, less homophobic universe, Mr. Ripley might have saved himself by using his considerable talents for good. Instead, he bludgeons the Comics Code established the year before he was published:

Crimes shall never be presented in such a way as to create sympathy for the criminal

No comics shall explicitly present the unique details and methods of a crime

Criminals shall not be presented so as to be rendered glamorous or to occupy a position which creates the desire for emulation.

In every instance good shall triumph over evil and the criminal punished for his misdeeds.

And most importantly:

Illicit sex relations are neither to be hinted at or portrayed. Violent love scenes as well as sexual abnormalities are unacceptable.

Sex perversion or any inference to same is strictly forbidden.

It’s enough to twist even Batman and Superman into sociopathic serial killers.