The final issue of Amazing Fantasy (No. 15) featured not only Spider-Man’s debut but three shorter Steve Ditko and Stan Lee collaborations, including “The One and Only,” a five-page tale made in the late 1950s and dropped into Amazing Fantasy as back filler. Ditko is credited for the art, but comics collector James Horvath, grandson of Golden Age artist Lydia Horvath, believes his grandmother actually drew it. Ms. Horvath was renowned for her ability to imitate other artists, including Joe Shuster for whom she ghosted as a member of his studio before leaving Cleveland in 1940 to begin her freelancing career with Timely and Paragon Comics.

The script for “The One and Only” was assumed lost, until Horvath recently discovered it in his late grandmother’s private papers. It is a parody of Golden Age knock-offs of Superman and features a Jimmy Olson-like character losing his newspaper job and searching for his beloved hero “Singulus” who went inexplicably missing during the 1950s. It has a dark twist ending which I won’t spoil, but here is an excerpt:

PAGE THREE, “The One and Only”

Script: Stan Lee

Row 1, Panel 1: Plane flying over the Himalayas. Caption: “Before vanishing, Singulus told Little Jim that he had gained his powers from a guru in the Himalaya Mountains. With nothing left to lose, Little Jim splurges on a one-way ticket to Tibet!”

Row 1, Panel 2: Close-up of Jim’s extremely foreshortened, rock-gouged hand reaching through a mist of mountain cloud for a ledge hold. Zoom in for the crosshatch of cuts and ragged nail edges.

Row 1, Panel 3: When Jimmy’s gritting face struggles over the ledge, he’s now has a scraggly beard and a few gray wires of hair over his still adolescently-round head.

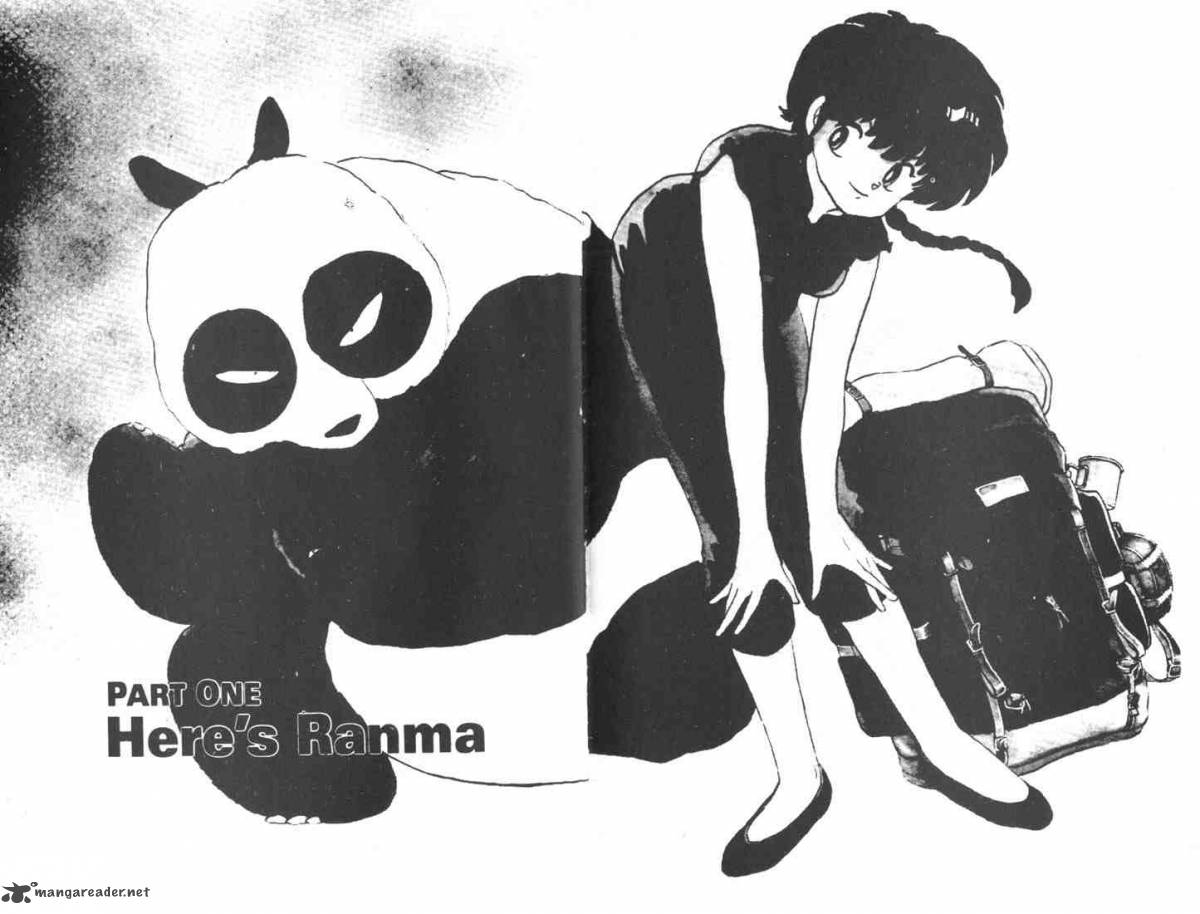

Row 2, Panel 1: Jim now fully on the ledge pulls out a flashlight from his removed backpack before entering the cave mouth.

Row 2, Panel 2: Jim’s round white eyes above the flashlight eye as he stumbles into the black of the secret cavern, with the cave opening now behind him.

Row 2, Panel 3: Jim’s POV, flashlight finds Singulus’ abandoned costume on the cave floor. Jim: “Singulus?”

Row 2, Panel 4: Jim’s POV, flashlight reveals the ancient guru Onlyone sitting cross-legged next to the costume. Onlyone: “At last the next heir to the Power Singulus has answered the calling!”

Row 3, Panel 1: Onlyone stretches out his arm, hand open with a ring in his palm. Jim reaches for the ring. Jim: “Me?” Onlyone: “I, Onlyone the Lonely One, Holy Keeper of the Power Singular, have been waiting to bestow this gift upon you.”

Row 3, Panel 2: Jim’s POV, as Onlyone watches him slide the ring onto his finger. Close up of finger and the ring with the letter “S” on it. Jim: “But I’m just Little Jim. How can I ever be—”

Row 3, Panel 3: Jim transforms into the new Singulus. His body mushrooms, newly superheroic shoulders shoving through the frame edges. The new Singulus leotard has bolder lines and darker colors than the discarded one shown earlier on the ground. Jim: “SINGULUS!!”

Row 3, Panel 4: Onlyone stands behind the new Singulus. Onlyone in spike-edged talk balloon, words in bold: “But remember!! The Power Singular is singular!! The cosmic charm was forged in secrecy and so in secrecy must remain!! The chosen one must stand alone or free his Secret Rival!!”

Sadly none of this is true. Lydia Horvath does not exist. Her grandson, James Horvath, is the fictional narrator of the novel The Patron Saint of Superheroes, which my agent is pitching to acquisition editors in New York publishing houses. The story is about Horvath’s attempts to preserve his dying grandmother by collecting her lost artwork—a mission that leads him to stealing the original printer pages for Amazing Fantasy No. 15 from a millionaire’s wall and later donating them anonymously to the Library of Congress. That actually did happen in 2008, and my novel is, among other things, the story behind that story.

My agent thinks the novel should also include the art for “The One and Only.” But that’s a little hard to do since the Ditko knock-off story doesn’t actually exist. At least not yet.

I’m looking for an artist interested in being Steve Ditko. Or rather an artist interested in pretending to be Lydia Horvath pretending to be Steve Ditko. If/when some wonderful editor buys the manuscript, the project will expand, but for the current pitching stage, we’re looking for one drawing. The page scripted above.

There’s plenty more to tell (the complete letter-like script was published as a short story in The Pinch in 2011, and the description of another Horvath comic as a prose poem last year in Drawn to Marvel), but these are the essentials. If you’re an artist interested in collaborating, contact me at chris@gavaler.com.