The summer superhero blockbuster season has officially commenced:

Avengers 2 opened in May, Ant-Man follows in July, and Fantastic Four in August. That’s only half of 2014’s six films, but 2016 will make up the difference with a record eight.

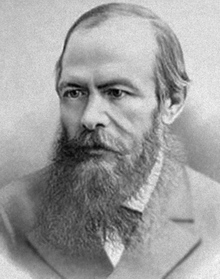

There was time when I thought the genre had an artistic future. But after Heath Ledger’s Oscar for playing the Joker, Warner Bros. and Marvel have only been interested in reproducing the same formula-driven commercial product again and again. So to analyze the nature of Hollywood superheroes, I’m calling in two experts from opposite ends of the literary spectrum: Fyodor Dostoyevsky, one of the most acclaimed novelists of Russian literature, and Blake Snyder, a third-rate screenwriter that Sylvester Stallone once likened to a flatworm.

I read Crime and Punishment in A.P. English as a high school senior—and I even finished it (a dubious honor my adolescent self did not award Moby Dick). I started The Brothers Karamavoz in college while working graveyard shifts as a warehouse security guard, but after totaling my Toyota on a sleepy drive home, I quit both.

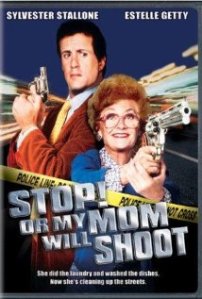

Snyder started his career writing episodes for the Disney Channel’s Kids Incorporated before going on to pen Blank Check and Stop! Or My Mom Will Shoot, a comedy Roger Ebert called “moronic beyond comprehension” and which its star, Sylvester Stallone, declared “one of the worst films in the entire solar system,” insisting “a flatworm could write a better script.” And yet when a good friend of mine—a former script reader for a California production company—wanted to collaborate on a screenplay, he handed me Snyder’s Save the Cat!

The how-to screenwriting guide explains why the Sandra Bullock comedy vehicle Miss Congeniality is a better movie than Memento. It comes down to formula: Miss Congeniality hits all 15 beats on The Blake Snyder Beat Sheet, while Christopher Nolan’s directorial debut “is just a gimmick that cannot be applied to any other movie.” If Snyder were a poetry professor, he would lecture about the superiority of sonnets to free verse, while defining the greatest works of literature by the uniformity of their iambic beats.

Rodion Raskolnikov, Dostoyevsky’s pawnbroker-murdering philosophy student, would classify Snyder as “ordinary.” Raskolnikov explains: “men are in general divided by a law of nature into two categories, inferior (ordinary), that is, so to say, material that serves only to reproduce its kind, and men who have the gift or the talent to utter a new word. . . . The first category, generally speaking, are men conservative in temperament and law-abiding; they live under control and love to be controlled. To my thinking it is their duty to be controlled, because that’s their vocation, and there is nothing humiliating in it for them.”

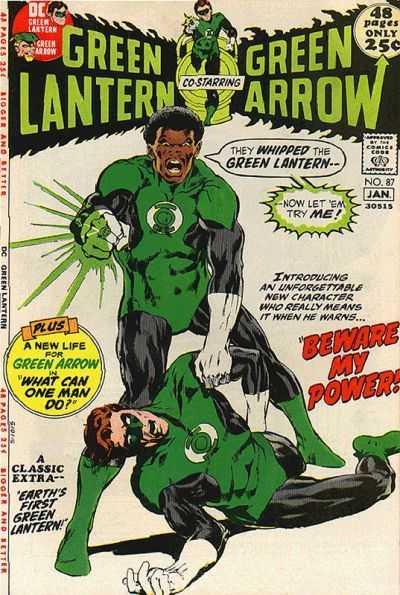

In other words, Hollywood spec writers play by the rules. And Snyder understands those rules well. He divides the universe into ten idiosyncratic genres. His “Dude with a Problem,” for example, includes Die Hard and Schindler’s List, while “Superhero” goes beyond Batman Begins to claim Gladiator and A Beautiful Mind—and probably anything else starring Russell Crowe. Snyder’s ur-Superhero is Gulliver surrounded by Lilliputians: “a Superhero tale asks us to lend human qualities, and our sympathy, to a super being, and identity with what it must be like to have to deal with the likes of us little people.” So Batman, Frankenstein, and Dracula are all Superheroes “challenged by the mediocre world around them,” because it’s really “the tiny minds that surround the hero that are the real problem.”

Raskolnikov would agree. His second category, “extraordinary” men, “all transgress the law,” because “making a new law, they transgressed the ancient one, handed down from their ancestors and held sacred by the people.” So “all great men or even men a little out of the common, that is to say capable of giving some new word, must from their very nature be criminals—more or less, of course. Otherwise it’s hard for them to get out of the common rut; and to remain in the common rut is what they can’t submit to, from their very nature again, and to my mind they ought not, indeed, to submit to it.” The rut-dwelling Lilliputians, meanwhile, will try to “punish them or hang them (more or less), and in doing so fulfill quite justly their conservative vocation.”

Snyder fulfills his Lilliputian vocation for Christopher Nolan when he shouts “screw Memento!” and dismisses all the “hulabaloo” because of its low box office revenue. That was in 2005, the year Batman Begins premiered, and three years before Heath Ledger won Best Supporting Actor for The Dark Knight. Raskolnikov warns that “the same masses set these criminals on a pedestal in the next generation and worship them,” and sure enough, Synder lauds Nolan’s caped crusader for following “the beats down to the minute.”

Or does that means Nolan is a Superhero who overcame his Gulliverness by conforming to the Lilliputian Beat Sheet? Either way, he, like Bruce Wayne “is admirable because he eschews his personal comfort in the effort to give back to the community.” That, says Snyder, solves the problem of “how to have sympathy for the likes of millionaire Bruce Wayne or genius Russell Crowe.” They save the cat.

And Raskolnikov agrees again. His “extraordinary man” has “an inner right to decide in his own conscience to overstep” if overstepping “is essential for the practical fulfillment of his idea,” and idea which might be “of benefit to the whole of humanity.” That’s how he rationalizes killing and robbing that nasty old pawnbroker. He argues (faux hypothetically) to a cop: “Kill her, take her money and with the help of it devote oneself to the service of humanity and the good of all. What do you think, would not one tiny crime be wiped out by thousands of good deeds?”

It doesn’t matter how the cop answers, because a real Gulliver wouldn’t have asked a Lilliputian for his opinion. That’s Raskolnikov’s downfall. He’s reading from the wrong page in Save the Cat! He wants to be a Superhero (“An extraordinary person finds himself in an ordinary world”), but he’s really just a Dude with a Problem (“An ordinary guy finds himself in extraordinary circumstances”). Worse, his circumstances are self-inflicted. He fell for Snyder’s Superhero formula because it “gives flight to our greatest fantasies about our potential.”

Raskolnikov fails to be “a man of the future,” but Nietzsche (who ranked reading Dostoyevksky “among the most beautiful strokes of fortune in my life”) took that “extraordinary” character type and renamed him the ubermensch. After Jerry Siegel adopted it, DC completed the circle by calling Superman “The Man of Tomorrow.”

But Dostoyevsky is no origin point. After explaining his theories, even Raskolnikov admits: “there is nothing particularly new in all that. The same thing has been printed and read a thousand times before.”Or as one of Snyder’s studio execs told him: “Give me the same thing . . . only different!”

That, sadly, is the state of the Hollywood superhero.