This piece originated as a paper presented at the 2015 University of Florida Comics Conference. A slightly different form of this paper was incorporated into my lecture “Change the Cover: Superhero Comics, the Internet, and Female Fans,” delivered at Miami University as part of the Comics Scholars Group lecture series. While I have made some slight changes to the version of the paper that I gave at UF, I have decided against editing the paper to make it read like a written essay rather than an oral presentation. The accompanying slide presentation is available here.

_________

First, I’m very grateful to be here because this is my first time back in Gainesville since I graduated from UF, and being here, I realize that I really miss it and that UF has played a major role in making me the person I am today.

So this is not something I’m currently working on, but it is something I’ve been thinking about extensively, and I think it may provide material for a future book or article project. It does relate to my earlier work on comics and Internet culture and it’s sort of a sequel to the paper I gave at ICFA last month, about comics and female fan culture. And this paper is based more on my personal than my scholarly knowledge. It’s based less on my scholarly work than on my many years of experience in organized comics fandom. I acknowledge that my discussion here would benefit from incorporating theoretical perspectives from fan studies, and that’s a direction I do intend to explore if and when I turn this into a longer work.

So as a general trend, what we might call geek culture or nerd culture or fandom has been steadily growing more inclusive. Whether we think of science fiction fandom or video gaming or comic books, each of these is a fan community that has traditionally been dominated by white men, but is gradually opening itself up to participation by women and minorities and LGBTQ people. In comics, for example, the comics industry has a notorious history of excluding women and younger readers, SLIDE 2 and there is a persistent and largely accurate stereotype of the comic book store as a man cave. SLIDE 3 But as I argued in my ICFA presentation, this is gradually changing. Titles like Raina Telgemeier’s Smile and Cece Bell’s El Deafo are dominating the bestseller lists SLIDE 4 and even Marvel and DC have sought to appeal to female and younger readers. SLIDE 5

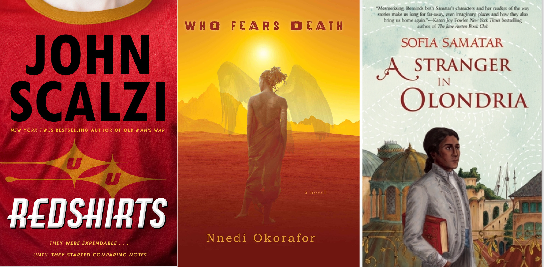

Now in other fan communities, the opening up of previously male-only spaces has triggered a backlash from the straight white men who used to dominate. The obvious example of this is Gamergate, where the inclusion of women in video gaming has led to an organized campaign of misogyny which has even crossed the line into domestic terrorism. SLIDE 6 A less well-known example is what’s been happening in science fiction fandom. In recent years, novels by liberal writers like John Scalzi and female and minority writers like Nnedi Okorafor and Sofia Samatar have dominated the major science fiction awards. SLIDE 7 When this started happening, certain mostly white male writers became extremely indignant that science fiction was becoming poiliticized, or rather that it was being politicized in a way they didn’t like. So they started an organized campaign known as Sad Puppies SLIDE 8 whose object was to get works by right-wing white male authors included on the ballot for the Hugo award, which is the only major science fiction and fantasy award where nominations are determined by fan voting. And this led in turn to the Rabid Puppies campaign, which was organized by notorious neo-Nazi Vox Day and which is explicitly racist, sexist and homophobic. SLIDE 9 And these campaigns succeeded partly thanks to assistance from Gamergate. On the 2015 Hugo ballot, the nominees in the short fiction categories consist entirely of works nominated by Sad Puppies and Rabid Puppies, and this has led to an enormous public outcry.

So across various spheres of geek culture, the move to open up these traditionally white male spaces has led to a backlash from white men who are afraid of losing their dominant position. Another way to look at this is that geek identity is historically bound up with white male identity. Being a geek or a nerd or a fan has traditionally meant being a person like me, a bespectacled athletically inept socially awkward white guy. As Dan Golding writes in the context of video games, “videogamers … developed a limited, inwards-looking perception of the world that marked them as different from everyone else. This is the gamer, an identity based on difference and separateness. When playing games was an unusual activity, this identity was constructed in order to define and unite the group … It became deeply bound up in assumptions and performances of gender and sexuality. To be a gamer was to signal a great many things, not all of which are about the actual playing of videogames.” SLIDE 11

And to an extent this is also true of comic book identity. Matthew J. Pustz wrote that “In most cases, being a comic book fan is central to fans’ identity.” And as Pustz goes on to write, the ultimate example of this is fanboys, or “comic book readers who take what they read much too seriously.” Stereotypically, fanboys are bespectacled, acned overweight misfits who have an encyclopedic knowledge of ’60s Marvel comics but have never spoken to a woman. And this stereotype is often cited in comics themselves, such as Evan Dorkin’s Eltingville Club stories. SLIDE 12

Now Golding goes on to discuss how gamer identity, as traditionally conceived, is under threat, because it’s too inflexible to survive the gaming industry’s increasing openness to female and minority and LGBTQ gamers. “When, over the last decade, the playing of videogames moved beyond the niche, the gamer identity remained fairly uniformly stagnant and immobile. Gamer identity was simply not fluid enough to apply to a broad spectrum of people. SLIDE 13 It could not meaningfully contain, for example, Candy Crush players, Proteus players, and Call of Duty players simultaneously. When videogames changed, the gamer identity did not stretch, and so it has been broken.” Thus, Golding’s article is called “The End of Gamers,” and he suggests that Gamergate is the last gasp of traditional gamer identity: that Gamergate is what happens when gamers as traditionally conceived realize that the concept of gamers no longer refers exclusively to them.

So the question I want to explore in this essay is whether this is also happening to comic book fans, and if so, what can we do about it. Is the category of “comic book fan” resilient enough to embrace people other than straight white males, or is comic fan identity going to be squeezed out of existence? My answer to that is twofold. On one hand, while comics fandom has not experienced anything quite as drastic as Gamergate or Sad Puppies, we have seen a certain backlash from misogynistic male fans who see comics as their exclusive property and who are resistant to the diversification of the medium. On the other hand, I believe that this sort of backlash has been a less significant phenomenon in comics fandom than in science fiction or video game fandom, and this is because being a comics fan has never been synonymous with being a stereotypical fanboy. For as long as I’ve been involved with it, comics fandom has always had at least some room for people other than straight white males. There has always been a significant segment of comics fandom that wanted to expand the reach of comics, and at least in my own circles, the stereotypical fanboy has been the exception rather than the rule. This is of course not exclusively true of comics fandom. Women have been prominently involved in gaming since before the dawn of the modern video game, as Jon Peterson’s Medium article “The First Female Gamers” brilliantly demonstrates, and science fiction fandom has an even longer tradition of female involvement. I focus on comics fandom here purely because this is the fandom with which I have the most personal experience, although I will speculate about some ways in which comics fandom may differ from other fandoms in terms of its openness to people outside its traditionally dominant demographic.

So in the first place, there clearly have been examples in which the diversification of the comics industry has led to a backlash from entitled fanboys. And these examples have mostly involved DC Comics because DC is the only major remaining company whose output is almost exclusively marketed toward fanboys, although that is starting to change slowly. Anyway, the most obvious recent example of fanboy backlash is what happened last month with the Batgirl #41 cover. SLIDE 14 I’m not going to describe this in depth because I assume most of you are familiar with it, but very briefly, DC announced a variant cover for Batgirl #41 which was an explicit reference to Batman: The Killing Joke, and which depicted Batgirl as a passive victim of the Joker. So there was a Twitter campaign to get DC to change the cover, and it succeeded because the artist of the cover, Rafael Albuquerque, asked DC to withdraw the cover, and DC agreed. Albuquerque wrote “For me, it was just a creepy cover that brought up something from the character’s past that I was able to interpret artistically. But it has become clear, that for others, it touched a very important nerve. I respect these opinions and, despite whether the discussion is right or wrong, no opinion should be discredited. My intention was never to hurt or upset anyone through my art. For that reason, I have recommended to DC that the variant cover be pulled. “ And then there was a competing campaign to get DC to keep the cover, and this campaign was supported by Gamergate. So this is evidence that some people at least see comics as the private property of men, and are violently resistant to the idea that comics should be sensitive about the depiction of violence against women.

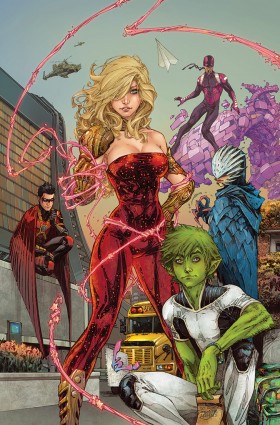

But I think we’re all pretty familiar with that incident, so I want to focus on another recent case of fanboy backlash, which is relevant to me personally because it involved an online community that I was a member of for many years. In April of last year, Janelle Asselin wrote an article for comicbookresources.com, commonly known as CBR, in which she criticized Kenneth Rocafort’s cover for Teen Titans #1. SLIDE 15 Specifically, Asselin complained that on this cover, Wonder Girl’s proportions are totally unrealistic – she’s a teenage girl but she clearly has breast implants. And she pointed out that this sort of depiction is explicitly problematic because this is a Teen Titans comic, and the various Teen Titans TV shows are widely popular among teenage girls and among children ages 2 to 11, SLIDE 16 and Rocafort’s cover is specifically designed to exclude those audiences.

Now Asselin was hardly saying anything controversial here. It’s pretty obvious that this cover is not only terrible but also misogynistic. And yet just for pointing out this obvious fact, she was not only criticized but threatened with rape. At the same time that she published the article, she released a survey on sexual harassment in the comics industry, which is also a significant problem, and some unfortunate trolls discovered this survey and filled it in by posting rape threats against Asselin. According to CBR proprietor Jonah Weiland, “These same “fans” found her e-mail, home address and other personal information, and used it to harass and terrorize her, including an attempted hacking of her bank account.” And according to Jonah, many of the fans in question were regular participants on the comicbookresources.com message boards, SLIDE 17 this character is the mascot of the CBR forums, and the harassment of Janelle Asselin was emblematic of an atmosphere of “a negativity and nastiness that has existed on the CBR forums for too long.” So because of this incident, he completely deleted everything on the CBR forums and restarted them from scratch with a new and much stricter moderation policy.

Now this incident is personally relevant to me because I was a member of the CBR forums for many years. I started posting on the CBR forums sometime around 1997 or 1998 when I was 14 or 15 years old. So I’ve been involved with this community for more than half my life. I was the moderator of the CBR Classic Comics forum and I used to run the annual Citizen of the Month award. I’ve gradually stopped posting at CBR because I’ve been annoyed at the way the conversation there is dominated by fanboys, although I still communicate with many of my old CBR friends via Facebook. So the Janelle Asselin incident seems like evidence that at least as far as CBR is concerned, comics fan identity has come to be defined in a way that excludes women and that emphasizes toxic masculinity.

At the same time, my experience at CBR is also what makes me hopeful about the future of comics fan identity, and it’s what makes me believe in alternative and more productive ways of being a comics fan. I started posting at CBR in the late ‘90s when I was a young teenager, and it was actually because of CBR that I gained the ability to think of being a comics fan in terms other than being a fanboy. Before I discovered CBR, most of what I knew about comics came from Wizard magazine, which was basically instrumental in defining the fanboy identity. SLIDE 18 If you’re lucky enough to not remember Wizard, basically it was the comics version of Maxim, the Magazine for Men. It was a sexist, homophobic rag that ridiculed women and that completely ignored comics that didn’t involve superheroes. In 2001, Frank Miller tore up a copy of it at the Harvey Awards banquet. And once I was camping out with some people I knew from CBR and we used a copy of Wizard to start a campfire. SLIDE 19

Anyway, at CBR I came into contact with comics fans who were much older and wiser than me, and these people convinced me that this way of being a comics fan was unsustainable. As long as comics were marketed purely to fanboys, comics were going to lose readership and they were ultimately going to be irrelevant, and this would be a bad thing. I think some of the people who told me this were themselves parents and were afraid that their children wouldn’t be able to grow up with comics in the same way that they did. SLIDE 20 And this experience convinced me that it was important for comics to be inclusive, that comics couldn’t continue to appeal to the same fanboy audience. Thanks to CBR, I grew up with the notion that comics needs to abandon its traditional target demographic or die. I think this is fundamentally different from the Gamergate mentality, which is driven by fear that games are becoming too popular and that the gaming industry is abandoning its traditional target demographic.

Perhaps the difference here is that the popularity of games is currently at its peak. While there are nagging fears of the death of big-budget video games, the gaming industry currently enjoys a huge audience, and game developers can still make a profit by producing games marketed toward the exclusive “gamer” demographic. Therefore, game developers and players may not see the need to reach out to new audiences. I’m not sure if the same is true of science fiction fans and publishers, but my sense is that science fiction literature also has enough of an audience that the industry is not facing existential threats to its survival.Conversely, the popularity of comics, at least in America, peaked during the ‘40s and ‘50s and has been steadily in decline since. SLIDE 21 Among the comics fans I grew up with, there was this notion that comics is a declining art form and that traditional concepts of comics fan identity are a threat to the long-term survival of the medium.

So I got this idea that in order to save comics, it was necessary to abandon fanboyism as the sole model of comics fan identity and to embrace a broader and more inclusive model of what it means to be a comics fan. According to this model, to be a comics fan is to be a lover and evangelist of the medium of comics, and to help expand the audience of the medium. And that’s what I try to do when I teach comics in first-year writing courses.

So this is a model of comics fandom that involves a certain radical openness to new audiences. And this notion of comics fandom is not just based on my personal experience; we also see it in things like Free Comic Book Day or in Michael Chabon’s 2004 Eisner Awards keynote addres where he called on the industry to do a better job of appealing to children. And I believe that if comics fan identity is defined in this way rather than in terms of fanboy identity, then to return to the earlier quotation from Golding, comics fan identity can be “fluid enough to apply to a broad spectrum of people.”