Last week I suggested that a TV show about time travel didn’t have to be completely stupid. This week I want to suggest that it could also be entertaining. Here’s a script treatment for a pilot to such a would-be non-completely-stupid yet-potentially-entertaining series. Interested TV producers should mail stacks of 1960s-era $100 bills to my home address.

“Remote Control”

Zoom slowly out from historical footage of President Kennedy’s May 25, 1961 Address to Congress: “I believe that this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to the earth. No single space project in this period will be more impressive to mankind, or more important for the long-range exploration of space.”

2015:

Remy is the granddaughter of two scientists who worked for NASA in the early years of the space race. Both died before she was born, so she is surprised to receive a visit from Connor, a lawyer executing her grandmother’s secret will. To receive the money left to her, Remy has to fulfill one obligation: exhume her grandmother’s coffin and store it in her house for one year.

1961:

Lora, Remy’s grandmother, is leading a small group of politicians and military officers into an airport hanger, promising them that what they are about to see will change everything.

In a second location, scientists lean over a control board in hectic preparation. They include Art, the handsome if good-humoredly arrogant team leader, and Tom, a comparative wall-flower. (Either could be Remy’s future grandfather.)

Lora throws open the door to the hangar to reveal: an anti-climatically empty hanger. Or almost empty. She directs the men to a line of folding chairs situated in front of small crate, drops her purse, and picks up a phone hanging from a pillar: “We’re ready.”

Art is on the other end, and the control room bursts into activity.

In the hangar, all eyes are on the crate. The moment intensifies until . . . the crate is still just sitting there. The observers are getting impatient. Lora snaps at Art.

Tom just solved the problem–they’re connected.

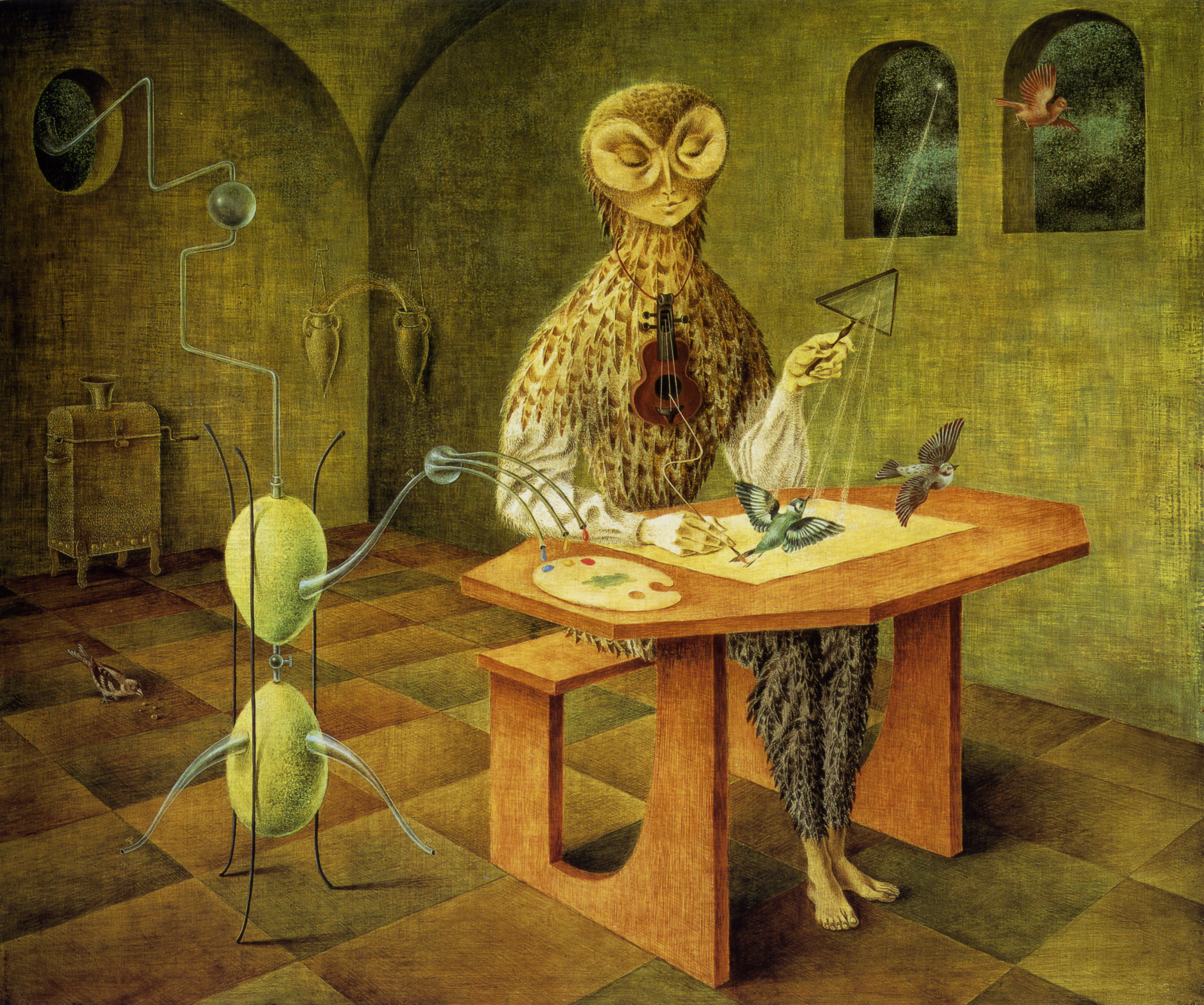

Lora looks at the crate: still nothing. She’s about to speak when she hears a crash through the phone and then jerks around as the crate crashes open a second later. A very non-anthropomorphic robot breaks out: it rolls on multiple wheels, extends an array of praying mantis-like arms, and swivels a camera eye at the startled observers.

The control panel’s central video screen shows the observers as the scientists control the robot’s movements. Tom mumbles something about theatrics: there won’t be any crates to smash on the moon. Art agrees, but politicians like a good show; that’s why he put Lora on the main stage.

Lora introduces LURC-er 1, a remote controlled robot designed for lunar exploration. The president has promised the world America will be on the moon by the end of the decade—which is impossible. How do you build a life-sustaining environment strong enough to withstand outer space and then make it lightweight enough to be rocketed out of the Earth’s gravity while still carrying enough food, water, and oxygen to keep even one human being alive? This will not happen in our lifetime’s or even our grandchildren’s lifetimes. But rocketing a robot to the moon is comparatively simple. LURC-er 1 rolls forward.

2015:

Remy and Connor watch as the coffin is dug up. When they open it, both are relieved to find not a desiccated corpse but a male mannequin dressed in a 60s-era business suit.

It and the coffin are trucked to Remy’s house and left in her empty garage. Connor says he will have to check in occasionally to confirm that the coffin remains in the house. The terms of the will are vague on this point, and he’s hinting that he might like to stop by more often than legally required. There’s some definite mutual attraction here.

1961:

Lora bounds into the control with the news: the observers were impressed, and project funding is guaranteed. Applause and celebration—including a lingering hug from Art. Tom looks away: “We still haven’t figured out the time delay.” This draws Lora’s attention away from Art. She could have sworn she heard the crate shattering through the control room speakers before it shattered in the hangar—but of course that’s impossible, and she laughs it off. Tom looks shocked. He mumbles something and starts poking at the controls. Art ignores him and draws Lora to an adjourning room where once alone they kiss.

2015:

Remy is woken by a faint noise downstairs. She finds her phone, preps it to dial 911, and arranges her keys in her other fist so they protrude as weapons. She turns on lights as she investigates the house, but finds nothing. Before giving up and going back upstairs, she checks the door to the garage: it’s unlocked. She opens it and hits the light but nothing has changed; the coffin is still sitting in the middle of the empty garage. She almost leaves but then walks to the coffin. She opens the lid: the mannequin is gone.

1961:

At night, Art is walking Lora to her car where they say goodnight with another kiss. Once inside she realizes she doesn’t have her keys—which are in her purse.

Lora enters the hangar where she left her purse earlier. She finds it and then hears a noise from one of the darkened areas. She notices that the folding chairs and broken crate haven’t moved—but the robot is gone. She explores and soon comes face to camera-eye with LURCer 1. It reaches a claw slowly toward her. She wants to smile, but can’t: “Art? Is that you?” The robot shakes its camera head “No.”

2015:

Connor wakes up to his phone ringing. It’s Remy explaining that the mannequin is gone and accusing him of playing some kind of game with her. Connor swears he knows nothing.

Remy hangs up angry. She is standing in her kitchen now when she hears something loud from upstairs. She dials 911 and reports an intruder in her house. She grabs her keys again and shouts warning that the police are coming as she walks upstairs. She sees a figure in a darkened corner. She throws on a light ready to punch, but it’s just the lifeless mannequin posed in a standing position. She approaches it cautiously. It remains frozen. She leans closer until her face is inches from it. A tense pause. Nothing happens.

1961:

The next morning, Lora, Tom and Art are back to work in the control room. Lora asks who was operating with LURCer last night, but they both deny it, and the panel recorded no activity. Tom is smiling though. He sits at the controls, saying he thinks he’s figured out the time delay. He activates LURCer and the screen shows the folding chairs and broken crate in the hangar. Why is it so dark? And where is everyone? Art is on the phone to the crew stationed in the hangar.

In the hangar, the crew is positioning the dormant LURCer; the crate and chairs are gone.

Art thinks Tom must have rolled the robot into the wrong area of the hangar somehow, but exploring reveals nothing. Lora’s face changes as she recognizes what is happening. She tells Tom to turn around—to turn LURCer around. When he does, Lora is looking back at them through the video screen. Are they watching a tape? The panel registers a live feed. Lora leans closer to the panel and speaks in sync with her lips moving silently on the screen: “Art? Is that you?” Tom looks at her, then operates LURCer: her image moves left and right as he shakes the camera “No.”

2015:

A police officer has finished taking Remy’s statement as two others report that the house and grounds are clear. Connor arrives, upset and apologizing. He explains that he is only following directives sent to him by an anonymous client. The police offer to remove the mannequin, but discover it’s surprisingly heavy. It topples rigidly onto its back on the upstairs landing. Remy tells them to leave it, and the officer assures her they will be patrolling all night and to call for any reason. Remy throws Connor out too, but first he gives her an envelope: the first payment, pre-sealed by the employer. She rips it open and stacks of $100 bills spill out. Remy watches at the window as Connor and the last police car pull away. She’s holding the bills and notices that they look unused but the design is wrong; they’re from the 1960s. A hand grabs her arm. She spins as a speaker behind the mannequin’s motionless lips says, “Remy, it’s me.”

1961:

Lora, Tom and Art are alone in the hangar with LURCer. Art has sent everyone else home. He checks that the door is locked, before Tom explains. The “delay” was due to the system he invented to synchronize signals between the control room and LURCer. It was just supposed to solve a technical issue, but the adjustment he made this morning proves that the signals traveled back and forth from a point in the past. He just invented time travel.

Although Tom has overthrown all of physics, Art points out that the technology has no practical application. They built LURCer two months ago, and so that’s as far back as they can send signals. Lora disagrees. Can’t the signals move forward in time? Isn’t that how she heard the crate break? The signals were traveling one second into the future. Why not send them further? How far is the range? It would only be possible if LURCer is maintained in the future too, either by their future selves or someone else. They leave the hangar, ready to find out.

2015:

Remy backs away from the mannequin. “What’s wrong?” it asks. She tells it take off its mask so she can see his face. “You know this isn’t a mask.” Remy flees as it moves toward her and then suddenly stops. “Oh,” it says and turns and vanishes into the kitchen. Remy waits, bewildered, then tentatively follows. She turns the corner to see it studying her wall calendar. It reads the date aloud and then looks at her. It says the date again. She nods. She flinches as it moves toward her again, but then it walks past her and heads upstairs. She follows it to her study where it is writing on a piece of paper at her desk. It seals the sheet into an envelope and hands it to her. “Hide this in one of your books.” It points at the wall of bookcases and then starts downstairs again. “What is it?”“The password. Have you called Connor yet?” “Password to what?” “I’m going back to the coffin now.” Remy leans over the banister as it descends. “Why do you want me to call Connor?” It pauses at the bottom. “And, Remy, remember.” It looks expressionlessly up at her. “Don’t trust me.” It vanishes around the corner.

1961:

Lora, Art and Tom sit at the control panel. They have no way to calibrate time distance, so Tom takes a guess—somewhere between a few seconds and a few millennia. To their shock, the signal is received. They’re connected. But the screen is black. Stranger, the new input doesn’t match their equipment—way more data than they can process. And the motor controls aren’t right either. They can’t get the wheels to engage properly. What has happened to LURCer?

2015:

Connor pulls up in front of Remy’s house and runs up the steps. She is waiting at the door: “Who are you working for?” He swears he doesn’t know and explains how his client handled everything through the mail. He never met or even spoke to anyone. Remy eventually accepts he’s telling the truth and starts to shut the door—when Connor asks if anything else happened. Did the intruder come back? Remy doesn’t answer, but clearly it has. He asks to come out, to stay somewhere else tonight, at a hotel—but then Remy opens the door and invites him. “You need to see this.”

1961:

They give up trying to work the motor controls. Did someone redesign LURCer? If so, at least the data they’re receiving will provide schematics for them to match the upgrade. The screen suddenly brightens as a lid lifts. Two faces look down at the camera. It’s Remy and Tom. “Who the hell are they?”

2015:

Remy and Tom hear noises as they approach the garage. As they enter, the coffin is jerking spastically, then stops. It jerks once more, then stops again. After a nervous moment, they open the lid and look down at the mannequin’s face.

1961:

Remy and Connor vanish as the screen goes dead. The signal has cut off.

In the hanger, LURCer comes alive and starts rolling outside.

They try reconnecting, but it’s as if the future LURCer is gone, or is being blocked, like a busy signal.

LURCer enters their building.

They continue trying controls and debating what just happened—when LURCer bursts into the control room. They step back. Who’s controlling it? It rolls toward them. Then stops. One of its arms extends to the floor and begins to scratch. Lora approaches—Art tries to hold her back—but she shrugs him off and kneels to study the scratches. They’re Morse code. “H-E-L-P.” One of the other arms has begun scratching and Tom reads it: “M-E.” Art reads the third arm: “K-I-L-L.” And Lora moves to read the fourth: “P-O-T-I-S.” What is Potis? Lora looks into the robot’s camera. “You want us to help you kill the President of the United States?” All the arms begin scratching again. They each read a letter: “Y” “E” “S.” They stand back as the arms keep scratching and scratching the same word over and over: YES YES YES YES YES

End on a slow zoom into historical footage of Kennedy’s Address to Congress: “Now it is time to take longer strides—time for a great new American enterprise—time for this nation to take a clearly leading role in space achievement, which in many ways may hold the key to our future on earth.”