Is Marvel Entertainment evil?

I compiled commentary from twelve experts, and the results are not good for superhero fans.

“I’m not going to head off and do a Marvel film,” director Peter Jackson said on the eve of his Hobbit 3 release. “I don’t really like the Hollywood blockbuster bandwagon that exists right now. The industry and the advent of all the technology, has kind of lost its way. It’s become very franchise driven and superhero driven.”

Since Jackson’s Lord of the Rings marked that technology advent, and since Jackson made all six of the Tolkien franchise films, that leaves superheroes as his only objection. He doesn’t like them. Or at least he doesn’t like Marvel—which, despite Warner Bros’ best efforts, is the same thing.

Even Marvel’s own Iron Man Robert Downey, Jr. sees the rust: “Honestly, the whole thing is just showing the beginning signs of fraying around the edges. It’s a little bit old. Last summer there were five or seven different ones out.”

Actually, there were only four superhero movies last summer, and though Marvel Entertainment produced only two (Captain America, Guardians of the Galaxy), the Marvel logo appeared at the start of the last X-Men and Spider-Man installments too. But you can’t blame Downey’s miscount. New York Times film critic A. O. Scott expressed a similar opinion after seeing Downey in The Avengers two year earlier: “the genre, though it is still in a period of commercial ascendancy, has also entered a phase of imaginative decadence.”

Alan Moore’s review was even more apocalyptic: “I think it’s a rather alarming sign if we’ve got audiences of adults going to see the Avengers movie and delighting in concepts and characters meant to entertain the 12-year-old boys of the 1950s.” Even The Avengers own director Joss Whedon acknowledges that audiences are tired of at least some aspects of the formula: “People have made it very clear that they are fed up with movies where entire cities are destroyed, and then we celebrate.”

And yet when a director attempts to shake-up the formula, Marvel fires them. Marvel’s Ant-Man went into production only because of Edgar Wright’s involvement, but when Marvel wasn’t happy with his last script, they rewrote it without his input, followed by a joint announcement that Wright was leaving “due to differences in their visions of the film.” Wright joined axed Marvel directors Kenneth Branaugh, Joe Johnston, and Patty Jenkins (as well as axed actors Edward Norton and Terrance Howard), all victims of similar differences in vision.

Is this the same risk-taking Marvel that hired Ang Lee to make his idiosyncratic Hulk? Is this the same Marvel that hired drug-addict Robert Downey, Jr. after Downey couldn’t stay clean long enough to complete a season of Alley McBeal? Is this the same Marvel that hired the iconoclastic Joss Whedon after his Buffy empire expired, his Firefly franchise flopped, and his Wonder Woman script never even made it into Development Hell?

Actually, it’s not.

Kim Masters and Borys Kit of The Hollywood Reporter explain: “Marvel and Wright were different entities when they began their relationship. Marvel was an upstart, independent and feisty as it began building the Marvel Studios brand.”

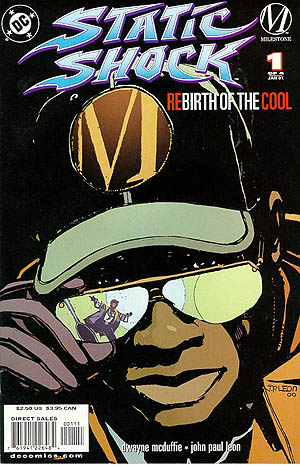

The Marvel I grew up reading, Marvel Comics Group, hasn’t been around since 1986, when its parent company, Marvel Entertainment Group, was sold to New World Entertainment. Technically, Marvel Comics (AKA Atlas Comics, AKA Timely Comics) ceased to exist in 1968 when owner Martin Goodman sold his company to Perfect Film and Chemical Corporation. The corporate juggling is hard to follow, but that next Marvel was sold to MacAndrews Group in 1989, and then, as part of a bankruptcy deal, to Toy Biz in 1997, where it became Marvel Enterprises, before changing its name to Marvel Entertainment in 2005 when it created Marvel Studios, before sold to Disney in 2009.

The real question is: at what point did Hydra infiltrate it?

I would like to report that the nefarious forces of evil have seized only Marvel’s movie-making branches, leaving its financially infinitesimal world of comic books to wallow in benign neglect. But that’s not the case.

Marvel comics writer Chris Claremont, renown for his 16-year run on The Uncanny X-Men, is currently hampered in his Nightcrawler scripting because he and everyone else writing X-Men titles are forbidden to create new characters. “Well,” he asked, “who owns them?” Fox does. Which means any new character Claremont creates becomes the film property of a Marvel Entertainment rival. “There will be no X-Men merchandising for the foreseeable future because, why promote Fox material?”

That’s also why Marvel cancelled The Fantastic Four. Those film rights are owned by Fox too, with a reboot out next August. Why should the parent company allow one of its micro-branches to promote another studio’s movie? Well, for one, The Fantastic Four was the title that launched the Marvel superhero pantheon and its subsequent comics empire in 1961. Surely even a profits-blinded mega-corporation can recognize the historical significance?

Like I said: Hydra.

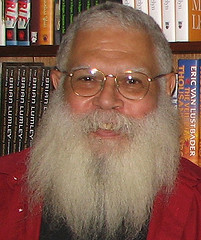

This is what drove former Marvel creator Paul Jenkins to the independent Boom! Studios: “It bugs me that the creators were a primary focus when the mainstream publishers needed them, and now that the corporations are driving the boat, creative decisions are being made once again by shareholders.” Former Marvel editor-in-chief Roy Thomas agrees: “There is a sense of loss because the tail is now wagging the dog.”

Compare that to Fantagraphics editor Garry Groth: “I think it’s a publisher’s obligation to take risks; I could probably publish safe, respectable ‘literary’ comics or solid, ‘good,’ uncontroversial comics for the rest of my life. I think it’s important, personally and professionally, to occasionally get outside your comfort zone.”

Marvel Entertainment is all about comfort zones. Even for its actors. “It’s all set up now so that you’re weirdly kind of safe,” says former Batman star Michael Keaton. “Once you get in those suits, they really know what to do with you. It was hard then; it ain’t that hard now.” New York Times’ Alex Pappademas is “old enough to remember when Warner Brothers entrusted the 1989 Batman and its sequel to Tim Burton, and how bizarre that decision seemed at the time, and how Burton ended up making one deeply and fascinatingly Tim Burton-ish movie that happened to be about Batman (played by the equally unlikely Michael Keaton, still the only screen Bruce Wayne who seemed like a guy with a dark secret).”

That’s the same Michael Keaton currently riding Birdman to the Oscars. How soon till Marvel’s Agents of H.Y.D.R.A. overwhelms that corner of Hollywood?