H.G. Wells was not a science fiction writer. Neither was Philip Nolan when he created Buck Rogers. But Flash Gordon—a Buck Rogers knock-off that appeared five years later—is science fiction. Aldous Huxley is harder to call. Brave New World appeared in 1932, three years after magazine editor Hugo Gernback invented the term, but it wasn’t in standard use yet. Others would have happily retained the older moniker “scientific romance.” Gernback preferred “scientifiction.”

Literary genres seem so monolithic—walk into a book store or skim a college course list—we forget they were ever contested. In 2009, Writer’s Chronicle blogger Emily Cross spotted a new genre, “a mix of literary and SF” that includes novels hard to label “fantasy/ science fiction/literary because they are both but neither.” Like 1920s scifi, it goes by more than one label, but the top two, “Slipstream” and “New Wave Fabulism,” are essentially “one and the same.” If the emergent genre follows the path of its predecessors, one of the terms will gain general acceptance and retroactively claim writers who never heard of it while writing its representative works, and the other term will go the dodo way of “scientifiction.” The change, however, involves more than naming rights. Rather than witnessing the birth of a new genre, or the reshuffling of works previously claimed by older genres into a hybrid category, we have a tectonic event affecting the wider literary landscape.

&nsp;

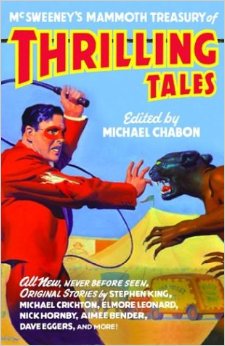

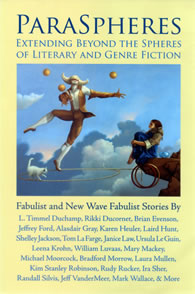

In Fall of 2002, Conjunctions editor Bradford Morrow handed over an issue of his “otherwise honorable literary journal” to the “conspicuously popular horror author” Peter Straub to guest-edit a volume of “innovative cross-genre science fiction, fantasy, and horror.” Six months later, McSweeney’s editor Dave Eggers handed his equally honorable journal to Michael Chabon for essentially the same project. Writers Kelly Link, Neil Gaiman, and Karen Joy Fowler appear in both volumes. Straub and Morrow subtitled theirs The New Wave Fabulists. Chabon and Eggers went for the retro-pulp Thrilling Tales. Neither name has stuck, but the shared project has. Two more anthologies appeared in 2006. Rusty Morrison and Ken Keegan’s Paraspheres: Extending Beyond the Spheres of Literary and Genre Fiction includes the additional subtitle Fabulist and New Wave Fabulist Stories—as well as Bradford Morrow in the table of contents and Peter Straub and Kelly Link in backcover blurbs. James Patrick Kelly and John Kessel’s Feeling Very Strange: The Slipstream Anthology includes stories from Michael Chabon, Kelly Link, and Karen Joy Fowler, plus Jonathan Lethem who, along with Kessel, is an alum of Straub’s Conjunctions.

So while the four sets of contributor pages are at times identical, the labels barely overlap. Chabon’s buzzwords are “entertainment” and “borderlands,” but he otherwise avoids naming his pulp reclamation project. When Eggers handed over a second, horror-heavy issue, they titled it McSweeney’s Enchanted Chamber of Astonishing Stories. Morrison and Keegan coined “paraspheres” because their selections “seem to extend ‘beyond the spheres’ of either literary or genre fiction.” But they also acknowledge Morrow and Straub’s term—while differentiating “New Wave” from earlier “Fabulists.” Phantom Drift, a recent entry in the literary marketplace, whittled the Conjunctions term down in their subtitle, A Journal of New Fabulism. Slipstream also has its own journal and history dating to the 1980s when the term was coined by science fiction author Bruce Sterling. Add the competing terms transrealism, new weird, speculative, interstitial, and literature of the fantastic, and suddenly Gernback’s “scientifiction” doesn’t sound so peculiar.

Rudy Rucker, another Paraspheres contributor, coined “Transrealism” in 1983 to describe works that treat “immediate perceptions in a fantastic way,” using “tools of fantasy and SF . . . to thicken and intensify realistic fiction” and so create “truly artistic SF.” Bruce Sterling’s 1989 “Slipstream” is more slippery to define, at times encompassing anything postmodern or, more vaguely, “anything that makes you feel very strange.” At other moments slipstream seems simply to denote “non-realistic literary fiction” or literary fiction with “fantastic elements.” David Memmott, currently the managing editor of Phantom Drift, started Ice River Magazine in 1987 “to explore, for lack of a better description, a literature of the fantastic . . . . literature of intersections” that included “Literary science fiction.” Phantom Drift is now “resisting the temptation to ‘tell’ the creative community what we mean by ‘new fabulism’ or a ‘literature of the fantastic’ by instead ‘showing’ you.” Chabon also resists, preferring to allude to the growing number of authors “in the borderlands among regions on the map of fiction.” Morrow adopts the same metaphor: “For two decades, a small group of innovative writers rooted in the genres of science fiction, fantasy, and horror have been simultaneously exploring and erasing the boundaries of those genres by creating fiction of remarkable depth and power.”

The geographic metaphors, however, suggest more than individual authors or communities sneaking between marked territories and establishing new colonies. The landscape itself has changed. Look at the non-borderland territory of contemporary fantasy. When Kevin Brockmeier guest-edited the 2010 Best American Fantasy, he and series editor Matthew Cheney subtitled their anthology Real Unreal. After describing the parallel traditions of “realistic fiction” and “the otherworldly,” Brockmeier asserts that “the branches of the ordinary and extraordinary are so tightly interwoven that it is nearly impossible to tell them apart.” He intends his selection as a gathering of “such grafted trees,” fantasy that takes elements from “the best realistic fiction.” This is the same literary project pursued by the emergent genre anthologies—except here it is held securely within the genre-protecting borders of Best American Fantasy. Brockmeier’s list of “ten favorite fantasy stories of all time” includes one by Theodora Goss, a Feeling Very Strange author, and the ubiquitous Kelly Link’s “Catskin,” one of Chabon’s Thrilling Tales. For his 2010 contents, Brockmeier also selected Feeling Very Strange contributor Benjamin Rosenbaum and editor John Kessel. The terrain is the same.

Fantasy, however, has been situated outside of traditional literary fiction, and so upheavals in its landscape do not necessarily reflect changes at literature’s center. Unless they do. When Brockmeier’s own story “The Ceiling” won the 2002 O. Henry Award, juror Joyce Carol Oates wrote: “It’s rare that a tale of dark fantasy makes its way into a mainstream publication, and still more rare to discover such a tale in the distinguished O. Henry Awards anthology where, through the decades, that category of prose fiction we call ‘realism’ has always predominated.” Oates admires how Brockmeier “conjoins the parable and the realistic story, the horrific with the domestic”—a variation on why Brockmeier admires his 2010 selections, and why all of the other editors admire theirs.

Oates, although a long-term borderland resident of horror, has a reputation firmly planted in literary fiction. Stephen King, however, does not—or at least did not when he won an O. Henry in 1996 and served as a juror in 1999. Chabon’s inclusion of King in Thrilling Tales wasn’t a breakthrough moment but the continuation of an arc. While Brockmeier included him in the 2010 Best American Fantasy, King’s “literary” standing expanded further with his novel 11/22/63, which earned a position on the New York Times best books of 2011. This is not evidence of an emergent genre. King is still writing horror—or, if you prefer, speculative fiction—but the landscape underneath him has shifted.

Similarly, Brockmeier drew almost half of his twenty 2010 fantasy stories from literary journals as honorable as Conjunctions and McSweeney’s: Tin House, New England Review, One Story, Oxford American, Kenyon Review, Pindeldyboz, and American Short Fiction. Dave Eggers published Brockmeier’s “The Ceiling” in McSweeney’s, but he, unlike his co-juror Oates, chose a traditionally realistic story for his 2002 O. Henry selection, as did the third juror, Colson Whitehead, who went on to publish Zone One, a literary zombie novel, in 2011—an unimaginable act a decade ago. When Brockmeier graduated to juror for the 2006 O. Henrys, he went with a work of realistic fiction, not Stephanie Reents’ story about a woman with a removable head, which series editor Laura Furman described in language that echoes the Slipstream and Paraspheres anthologies published the same year: it “is heartachingly familiar, but it feels like new literary territory.”

But is it new? As I glance through my shelf at a few O. Henry and Best American Short Stories anthologies of the last decade, I find works about an android, a village on the back of a giant whale, and an eleven-fingered pianist. If these fantastical stories appear firmly in the literary mainstream—what slipstream, etc. define themselves against—then we’re not talking about an emergent genre. We have a change at the core of contemporary literature.

The center does not hold. Or rather, literature now maintains multiple epicenters. If the metaphor is territories, then today’s authors have more than just passports; they have dual citizenships. Take my short story “Is” as an example. It first appeared in New England Review in 2008, then Brockmeier’s Best American Fantasy in 2010, and its sequel, “Isn’t,” appeared in Phantom Drift in 2012. Together “Is” and “Isn’t” are and are not “literary fiction,” “fantasy,” and whatever term you prefer to call the not-so-new genre-linking genre of Linkism. (Kelly Link, by the way, identifies herself as a science fiction writer.)

While the varied Linkists can’t always agree on what they are and aren’t, they do agree on what “literary fiction” is and isn’t. Keegan identifies the primary meaning among U.S. academic institutions as fiction that has “lasting meaning and value,” but within the publishing industry, literary fiction denotes “narrative realism,” as opposed to any other genre with its equally and inevitably artificial conventions. The conflated term limits quality to realism. Chabon reduces the problem to one word: “serious.” Literary fiction is, everything else isn’t.

Or, I should say, wasn’t. The monolithic realism that spurred all of this border crossing and boundary shifting is gone. Once four 21st century Pulitzer winners—Michael Chabon, Michael Cunningham, Cormac McCarthy, and Junot Diaz—have written about alternate timelines, androids, post-apocalyptic futures, and magic mongooses, traditional realism can no longer be claimed as a prerequisite of contemporary literary fiction. Add, in no particular order, Philip Roth, Sherman Alexie, Isabel Allende, Jane Smiley, Tom De Haven, Kazuo Ishiguro, Jennifer Egan, David Mitchell, Don DeLillo, Austin Grossman, Lev Grossman, George Saunders, Glen Duncan, Tom Perrotta, and Caryl Churchill to the already long list of fabulous slipstreamers, and we’re no longer describing authors migrating between genres. The genres themselves have been leveled.

Soon they may never have been there at all. Just as H. G. Wells became the retroactive father of science fiction, 20th century authors previously ensconced in narrative realism will emerge as fantastical realist godparents. Reread Joyce Carol Oates’ widely anthologized “Where Are You Going, Where Have You Been?” or John Cheever’s equally canonical “The Swimmer.” Or better, come up with an argument for why one of the most highly regarded novels of the 20th century, Toni Morrison’s Beloved, is not first and foremost a horror story.

When I teach the contemporary novel at Washington and Lee University, I subtitle my course “Thrilling Tales.” The challenge is limiting the syllabus. Chabon’s anthology title—a fanciful act of literary transgression a decade ago—now describes a wide swath of “serious” mainstream fiction. Chabon’s dream of literary eclecticism has come true. Werewolves, time-travelers, clones, superheroes—nothing is out of bounds.

Or almost nothing. Despite the leveled landscape, one gulf still divides “literary” and “non-literary”: formula. This is not a hold-over prejudice from old school literary fiction. The bias was articulated early and often by the genre-splicing outsiders. After declaring that “straight realism is all burnt out,” Rucker demands that a “Transrealist artist cannot predict the finished form of his or her work. The Transrealist novel grows organically.” While defining slipstream, Sterling bemoans the state of category SF for its “belittlement of individual creativity, and the triumph of anonymous product.” He could be describing the vast majority of novels mass produced in the heyday of the pulp magazine industry. Despite his revisionist nostalgia, even Chabon acknowledges the “formulaic nature of genre fiction,” shifting the blame toward publishers and book-sellers. It was their marketing practices and formula-driven products that originally prompted a generation of writers and editors to construct “literary fiction” as a boundary against them.

But formula is not innate to any genre. Octavia E. Butler identified herself as a science fiction writer—not speculative fiction or anything else—until her death in 2007, because SF “was so wide open, it gave me the chance to comment on every aspect of humanity. People tend to think of science fiction as, oh, Star Wars or Star Trek, and the truth is there are no closed doors, and there are no required formulas. You can go anywhere with it.”

In short, the new literary landscape allows anything but a convention-determined plot outcome. Although romance was a major pulp category in the first half of the century, Chabon did not include any representatives in his Thrilling Tales. Despite its use of realistic surface details, romance is definitively formulaic. The reader begins with the guarantee of two lovers united. Throw in as many obstacles as you like, but the conclusion is set. Mystery and detective fiction offer a similar problem. Poe’s writing dictum still holds: begin with the end and work backwards. This might explain why only Chabon champions the mystery subgenre. He’s written two detective novels (Chabon maintains citizenships in an enviable range of territories), but the other anthologists mostly limit themselves to science fiction, horror and fantasy—anything that bends the conventions of realism. Detective fiction, like romance, behaves like realistic fiction. Only its deep structure—the requisite agreement between writer and reader that the detective will solve the mystery—separates it from narrative realism. Superheroes—once the greatest amalgam all things non-literary—were embraced as “serious” literature only after their old plot requirements collapsed. Alan Moore’s Watchmen upended the 1954 Comics Code dictum that “In every instance good shall triumph over evil and the criminal punished for his misdeeds.” Flying men in tights are easier for literary fiction to swallow than a formula-mandated ending.

It sounds easy. Just yank out the plot rug and let the genre pieces—aliens, elves, gangsters, it makes no difference—rattle into new configurations. Michael Cunningham’s Specimen Days, however, shows how tricky old school genre plotting can be. The middle section of Cunningham’s 2005 novel is written in the style of a police thriller, which requires certain characters to be at certain places at certain times. In order to chance into the terrorist suspect, for instance, Cunningham’s cop has to have a coincidental reason to return to her apartment where he’s secretly waiting. Narrative realism requires the reason to appear organic, but Cunningham, like most narrative realists, doesn’t have much practice with plot-defined storytelling. When his cop mouths an authorial excuse for her detour home, Cunningham’s strings show. Frankly, it’s a little embarrassing—which is why “literary fiction” shunned pulp genres for so long and so successfully.

But the fact that Specimen Days even exists—with its gothic tropes in part one and its aliens and androids in part three—is evidence alone that something very strange happened in the first decade of the new century. Cunningham is not a Transrealist, Magic Realist, Slipstreamer, Paraspherist, or New or Old Wave Fabulist. He’s a mainstream literary fiction writer.

Welcome to 21st Century Literature.

[This essay originally appeared in The Writer’s Chronicle.]