“It is folly to believe that you can bring the psychology of an individual successfully to life without putting him very firmly in a social setting.”

-Tom Wolfe

A few months ago, writer Linn Ullman (daughter of director Ingmar Berman and actress Liv Ullman) talked to The Atlantic about her understanding of setting in narrative approach. Inspired by the short stories of Alice Munro, Ullman said:

Those precious few settings where something happened are where meaning resides—they contain the story, they are the story. Yes, I think that, to Alice Munro, story is place—the two are that deeply connected. You do not have a story of a life without an actual place. You can’t separate one from the other.

Reading that interview, I was struck by how applicable this is to comic book storytelling. One of the major strengths of the comic book medium is its unique capacity for placing readers squarely within a specific setting, a characteristic that feeds directly off the primacy of the medium’s visual dimension.

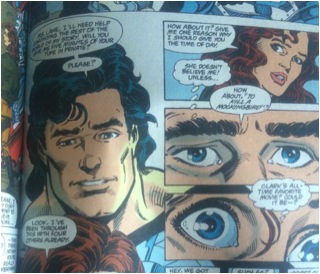

Unlike film or books, static page layouts allow a reader of graphic fiction to dwell equally on minutia and panorama, to experience the past alongside the present. With other forms of fiction, we’re always looking at or thinking about one thing at a time; temporally, we’re constantly caught up in the “now” of the narrative.

But graphic fiction generally has no “now” per se; rather, a typical comic book page viewed holistically is a representation of a certain big picture, i.e. an expression composed with a certain temporal simultaneity and visual dexterity between high and low abstractions of detail.

There are few comic book writers today that demonstrate this with greater aplomb than Jason Aaron.

In the past several years Aaron has emerged to be one of the most successful scribes of the comics world, due in large part to his “one for you, one for them” approach to the business. Like other prominent Marvel writers such as Ed Brubaker and Matt Fraction, Aaron is able to balance his spandex work with personally meaningful projects.

After garnering an Eisner nomination in 2007 for his Vietnam graphic novel The Other Side, Aaron pitched Scalped to DC/Vertigo. Initially conceived of as a Scalphunter reboot, Scalped quickly blossomed into an epic, beautiful Western-Noir saga about one community’s struggle with economics, circumstance, family, racial identity, morality, violence, spirituality, authority, and just about everything in between.

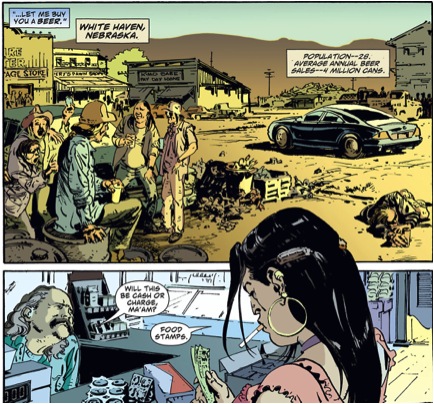

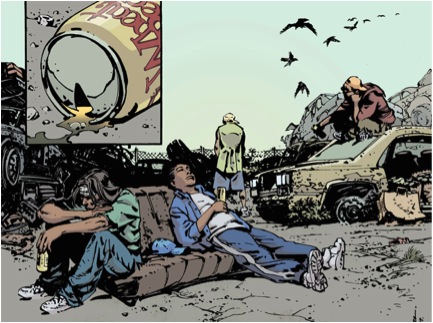

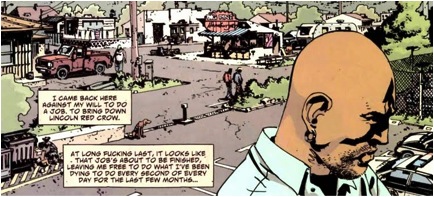

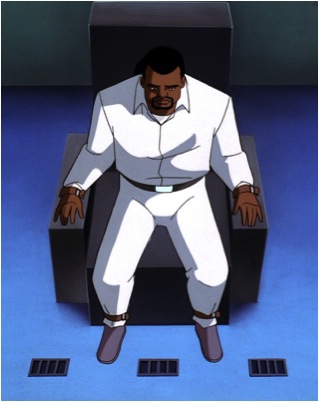

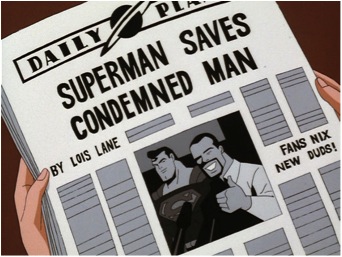

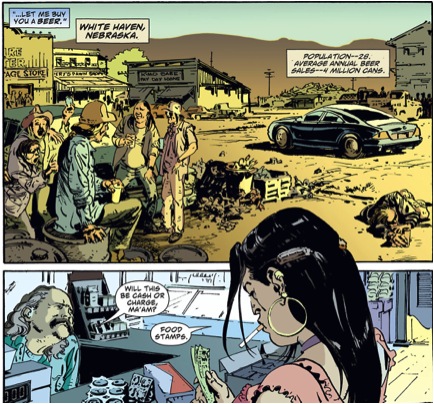

The most striking thing one feels opening an issue of Scalped is the immediacy of its setting. Aaron’s story takes place on the Prairie Rose Indian Reservation, located in the dusty, desolate plains of South Dakota. With enormous help from the book’s remarkable artistic staff, including detailed pencils from R.M Guera and warm sepia tones from talented colorists like Giulia Brusco, Scalped teems with human life like no other comic I’ve seen before.

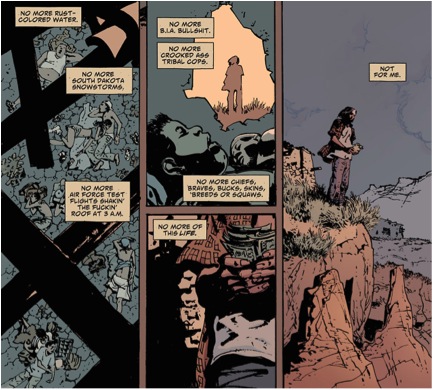

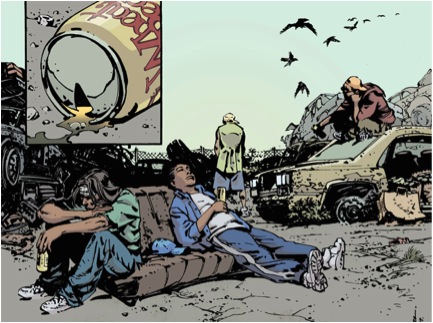

A great example of this is issue #10, which serves as a heartbreaking and poetic ode to ethnic ambivalence. “My Ambitionz Az a Ridah” focuses on Dino, a young and disaffected fuckup who’s grown weary of his crummy rez lifestyle. Like all teenagers everywhere, he longs for escape and fetishizes the idea that he is somehow different, and thus truly alone, in his environment.

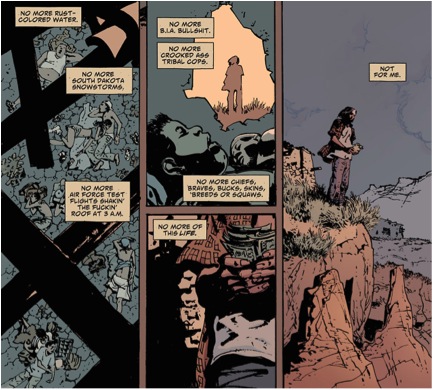

Dino fantasizes about leaving as he slogs through a typical day, and his narration eventually takes the form of a laundry list of precious details about his home.

“No more living in the ass-end of nowhere in a tiny little piece a’ shit house with mice in the attic and black mold on the walls. And eight other people sharin’ the space. No more livin’ without cable TV. Without cell phones. Without the internet. No more jigglin’ the rabbit ears for my fat-ass uncle so he can sit on the couch and watch westerns all day.”

The issue is a masterful depiction of how interdependent personal depression is with social deprivation; external misfortunes are directed inwardly as self-hatred, and again redirected outward as rage against one’s community.

But the clever hook of the issue is how Dino’s resentment eventually transforms into a kind of guilty affection for reservation life. Given the opportunity to leave for good, Dino decides to stay. He sees that abandoning the things he hates about his life would mean abandoning the things he loves too. It’s as if for a moment he comes to understand, however vaguely, what Erik Erikson emphasized as the inter-penetrability of character and culture:

“For we deal with a process ‘located’ in the core of the individual and yet also in the core of his communal culture, a process which established, in fact, the identity of those two identities.”

In this issue and throughout Scalped, we don’t see conflict occurring within a particular setting, but rather that setting is the conflict insofar as character and culture form a dialectical relationship. When the series concluded in 2012, Aaron told Wired:

The selling point of the book was always the setting. Plot-wise, there’s nothing particularly groundbreaking about Scalped. It starts off as something we’ve seen plenty of times before…the twist was always the setting: a modern-day Native American reservation. Given that, the reservation always had to be a character in the book.

So for Aaron, setting isn’t just about placing characters in a context in which they can bump up against each other. Rather, it’s about creating a place that is itself a character, one that interacts with other characters and undergoes its own meaningful story arc.

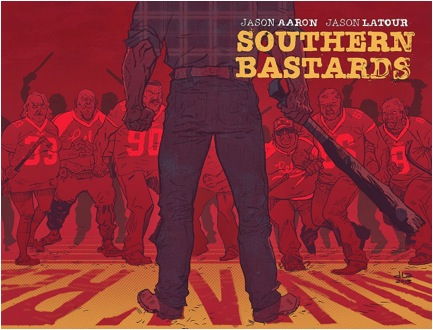

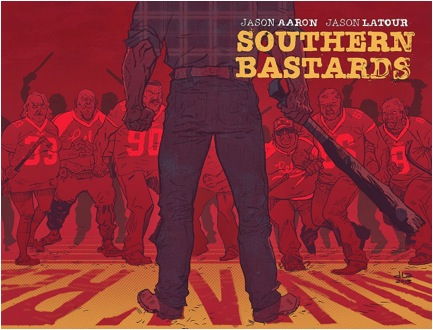

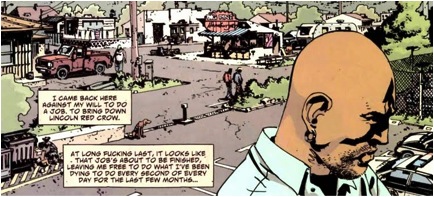

Aaron’s newest title Southern Bastards also demonstrates this emphasis on setting. Like Scalped, the title has its protagonist returning to his hometown after a long and very deliberate absence. Both stories feature characters in the process of rediscovering a now-alien environment that nonetheless forms the unconscious basis of their personality, however much their conscious ego wants to deny it. The trick to communicating this sophisticated treatment of setting is in the details.

Consider the first page of the first issue. We’re shown a small grass clearing at the threshold between an interstate highway and the woods that line it. Around the perimeter we see crooked signs for several different Christian churches; Freewill Church of God in Christ is three miles away on Water Tower Road, and Bible Belt Baptist Church boasts the slogan “HELL: ONE WAY IN AND NO WAY OUT. WELCOME.” In the center of it all is a mangy dog taking a spiteful shit on the ground.

This tells you nearly everything you need to know about Craw County, Alabama.

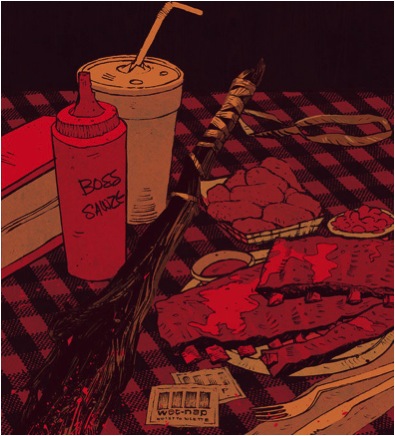

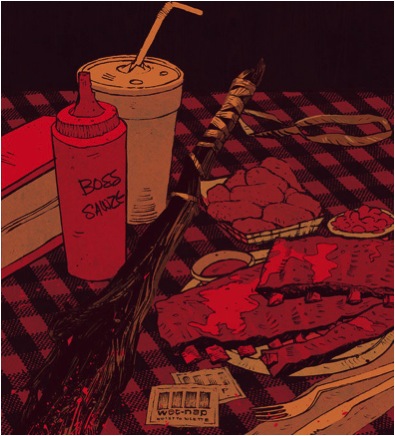

As the series progresses, Aaron continues to paint Craw County as a mosaic of very specific details: every small business seems to be owned by a man named Coach Boss; a rib joint waitress named Shawna offers sweet tea and fried pie; a redneck goon has tattoos that combine Confederate and Satanist imagery; a dead father’s club is symbolic of lost phallic potency; and references to football are everywhere.

This is similar to what Tom Wolfe has said about the way he wrote about New York City.

“I realized instinctively that if I were going to write vignettes of contemporary life, which is what I was doing constantly for New York, I wanted all the sounds, the looks, the feel of whatever place I was writing about to be in this vignette. Brand names, tastes in clothes and furniture, manners, the way people treat children, servants, or their superiors, are important clues to an individual’s expectations.”

Likewise, Aaron wisely declines to merely talk about Craw County. Rather, he and artist Jason Latour are committed to showing us Craw County, slowly, through a series of tiny revelations.

At the heart of both Scalped and Southern Bastards is the way in which individuals position themselves with respect to their originology. Resentment for where we come from is rooted in a gnawing discomfort with who we come to be. Aaron’s characters see the past as exerting a kind of gravitational force over them. It follows them around and makes demands in the form of guilt. This is as true of their towns as it is of their parents –in Scalped it’s Dash’s mother and in Southern Bastards it’s Earl’s father, both figures giving body to the invisible landscape of repressed unconscious. It is our origin that always threatens to swallow us back up, particularly when, like Dash and Earl, we’ve spent so many years trying to get away from it. To appreciate this level of characterization, it’s essential we be put in meaningful touch with setting.

All of this is to say, if you haven’t checked out Jason Aaron’s work, in particular his non-superhero stuff, you really need to. Setting is important in all forms of fiction, but I hope with the above I’ve at least begun to point out how comics accomplish this like no other form can.

As serious fans of the comic book medium, it’s important that we pay attention to the things that comics can do that other forms of storytelling cannot. Today, it’s more important than ever to recognize that comic book storytelling is far more than mere Hollywood blockbuster precursor –it’s an essential and unique medium in its own right.