Peter Sattler tagged me in this facebook meme asking me to list 10 books that really stuck with me, from all times of my life. I usually avoid these social media gauntlets, but I did this one, because I don’t know why. I tried not to think about it too hard and probably failed. I’ve linked to essays I’ve written about the writers/books (unless I haven’t written about them.)

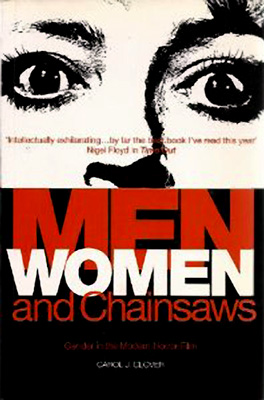

1. Carol Clover, “Men, Women, and Chainsaws”

2. James Baldwin, “The Price of the Ticket”

3. Richard Wright, “Black Boy”

4. Alan Moore/Dave Gibbons, “Watchmen”

5. Jack L. Chalker, Soul Rider series

6. Marston/Peter, Wonder Woman

7. Sharon Marcus, “Between Women”

8. Jane Austen, “Pride and Prejudice”

9. H.P. Lovecraft, “Shadow Over Innsmouth”

10. Ariel Schrag, “Likewise”

11. Wallace Stevens, “Palm At the End of the Mind”

12. Ian McEwan, “Atonement”

13. George Eliot, “Middlemarch

14. C.S. Lewis, “Til We Have Faces”

15. Stephenie Meyer, Twilight Series

16. Foucault, “History of Sexuality”

17. Philip K. Dick, “The Man in the High Castle”

18. Ursula K. Le Guin, Earthsea Series

19. Cecilia Grant, “A Gentleman Undone”

20. Julia Serano, “Whipping Girl”

21. Gerard Manley Hopkins, collected poems

22. Octavia Butler, “Xenogenesis”

23. Julia Cameron, “The Artist’s Way”

24. Ai Yazawa, “Nana”

25. James Loewen, “Lies Across America”

26. Samuel Delany, “Stars in My Pocket Like Grains of Sand”

27. Grace Llewellyn, “The Teenage Liberation Handbook”

28. George Bernard Shaw, “A Book of Prefaces”

29. Eve Sedgwick, “Between Men”

30. Tabico, “Adaptation”

Obviously, not thinking about it too hard meant in part not being able to count. I think the earliest one of these I read was probably Black Boy, which I believe is from fifth grade or thereabouts. The Earthsea books might be from around then too, and the Jack L. Chalker was early on — probably middle school. Oh, and the H.P. Lovecraft would have been from around then too. I don’t think there’s anything on here that I was actually assigned in college, which is a little weird, but I read “The Man in the High Castle” at that time. (I thought about including Immanuel Kant’s Critique of Practical Reason, but I can’t say it’s the book that’s stuck with me as much as a couple of the ideas; thought about Elshtain’s Women and War, too.) The most recent things here are the Cecelia Grant and the Ian McEwan. Most are books I love…and probably not coincidentally many are books that made me cry (Yazawa, Grant, Loewen, McEwan, Lewis). There are a couple that I don’t think are very good though; that would be Chalker, Meyer…and Cameron’s on the list because that’s the worst book I’ve ever read. The Delany was on my headboard in high school for years and years without me reading it; I dragged it all the way out to Chicago with me, I think, and finally got through it…and didn’t exactly like it. I still think about it, though, in a way I don’t with lots of books I’ve enjoyed more. I should reread it someday. (I haven’t managed to find any other Delany I like at all. I thought the essays might work, but I started a volume of those recently and was bored and irritated.)

Though I’ve only read Delany once, I’ve read many of these numerous times; probably read Baldwin and Austen most, and maybe Loewen and Shaw and Cameron (the last of whom I read multiple times for work reasons.)

The list definitely tilts towards the cis het white guys, but it could be worse in that regard, I guess. 17 guys, 13 women; only 5 non-white folks. 9 LGBT writers (Baldwin, Marcus, Schrag, Hopkins, Foucault, Delany, Serano, Tabico and Butler…who I hadn’t been sure was lesbian, but the web seems to agree she was. Sedgwick might fit too…her identification was complicated.) So that’d be 10 cis het white guys altogether (if you count Moore/Gibbons and Marston/Peter as one each). Only about a third, but the single most represented group, it looks like. I’m all about my demographic. (Though I think Schrag is the only Jew on there? Oh, and Eve Sedgwick. Might be another one or two; we assimilate and are hard to find.)

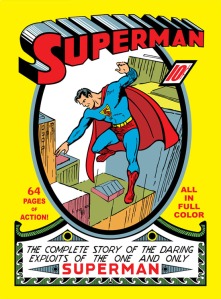

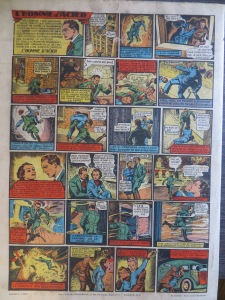

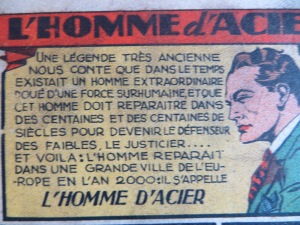

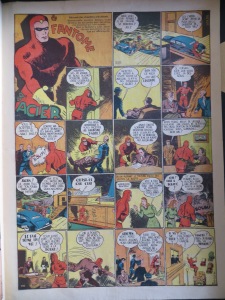

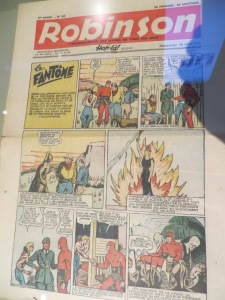

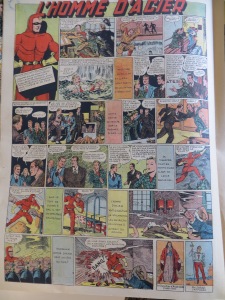

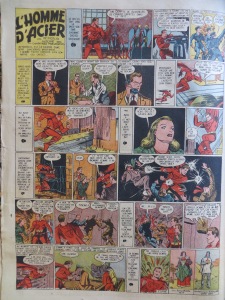

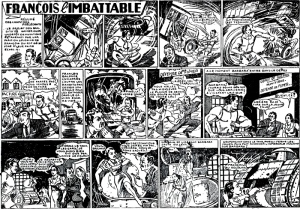

12 nonfiction, 2 books of poetry, 16 fiction, 3 comics. Sci-fi is I think the most represented genre with 4 titles (Delany, Butler, Chalker, Tabico — Dick might count too as alternate history, depending on how you look at it, and I guess Lovecraft might too depending on if you think evil creatures from outside of time are sf or fantasy). Romance is in there and personal essay and academic books and horror and superheroes and lit fic and some classics and YA and porn and autobio and even self-help (Cameron and Llewellyn), but no mysteries (unless you count Watchmen, I suppose). That’s about right; mystery isn’t a genre that I’ve ever had much of a relationship with. I thought about including Agatha Christie’s “Murder of Roger Ackroyd”, which I read when I was a kid; not sure I can honestly say I care about it too much any more, though. Also no plays; I thought about Pygmalion but picked Shaw’s essays instead. I’m sure I could pick some Shakespeare too…

All right, that’s enough babbling. If you want to put a list in comments, please do (you can copy and paste if you already did it on facebook). I’m curious to see what other folks would pick (whether 10 or more.)