This is part of the Gay Utopia project, originally published in 2007. It is reprinted by permission of EyeofSerpent, and may not be reproduced. A map of the Gay Utopia is here.

This is erotic fiction and NSFW in any way, so be warned.

_____________

Corelle D’Amber walked into my office without fanfare and I returned her firm handshake. Quick observations; she was average height with auburn hair that saw more sunshine than I expected, she seemed mid-thirties, but I knew she was ten years older than that, and she really knew how to dress. Suede pumps, silver bracelets that matched the design of her earrings, and a white carnation in her lapel. She was sporting a very nice charcoal suit with a tiny pearlescent pinstripe. The patch over her eye was exactly the same material as her suit, even to the extent that the pinstripe was neatly aligned with her jacket.

I put aside the instant recognition of a personality obsessed with detail. I was hoping for Ms. D’Amber’s help with this case. I just wouldn’t have time to get to know the woman that Forbes magazine called “the most successful entrepreneur since Edison.” She was a millionaire by thirty, a billionaire now. She could afford to indulge her own tastes.

I gestured, “Please take a seat, Ms. D’Amber. I’m so glad you could fit me into your schedule.”

“Thank you, doctor. When we spoke on the phone, you suggested that Mrs. Roth would sincerely benefit from my meeting with you to discuss her case.” She eased herself into the maroon leather chair.

To put her at ease, I sat in the twin to it rather than behind my desk. This was a woman who knew most business interaction from every angle. I didn’t make the mistake of thinking that establishing trust with her would be a matter of quickly pushing the right buttons. Just getting her here was a plus. “Ms. D’Amber, how much do you know about Alice’s situation?”

She didn’t bat an eye, “I’ve worked with her husband, Bill for nearly six months. I’ve met Alice many times on my trips into town. We’ve even gone to dinner together. I don’t know anything about why she’s seeing a psychiatrist. I’d be surprised if you were going to tell me. Client privacy and all that?”

Sharp. “Yes,” I smiled, “but Alice has also been to see two other psychiatrists by court order. I’m not sure what the court will do if a third one throws up their hands on her case. I’m hoping for some good news.”

That got her attention. I could see natural curiosity working away beneath her surprise; “No one has said anything to me. Bill never mentioned this. What crime has she committed?”

“Public indecency. Multiple counts. It’s not a serious crime, but the judge asked for a psychiatric review.” I watched her for a reaction. Most women were actually very conservative about things like this. Women who ‘broke the rules’ were first scorned by other women.

“Alice? Hard to believe. There must be some mistake.” She shook her head.

Good. At least she wasn’t blaming Alice. Now for the hard part. “No. There is no mistake. Alice even admits to flashing in situations where she hasn’t been caught. Ms. D’Amber, I asked you here to help because I’m sure Alice wants to stop. I’ve gotten her interested in changing her behavior. Part of that change involves asking for you to help her.”

Now she did look wary, “Why me? Why not you, you obviously don’t approve of this behavior?”

I laughed gently, “No. Of course I don’t approve. This sort of degrading attention-driven behavior is a cry for help. Even Alice is very embarrassed by how far she has taken this. Her family and friends are aware there is a problem, if not how serious it is. Her husband is nearly beside himself with the stress. Alice has chosen you, I think, because you are a role model, someone of impeccable taste. Someone who is used to making decisions. Someone she knows is a respected woman.”

“I still don’t understand what help I could be.” She didn’t look pleased. Her face was showing all the signs of ‘discussion closed’. She had a nice straightforward face, not pretty, but she could afford to take care of herself and she obviously had a sense for what worked for her. Simple. Almost an inner elegance. Just this short meeting and I could see why Alice had fixed on Corelle D’Amber as the matriarchal figure who’s permission and forgiveness she needed in order to stop her increasingly degrading activities.

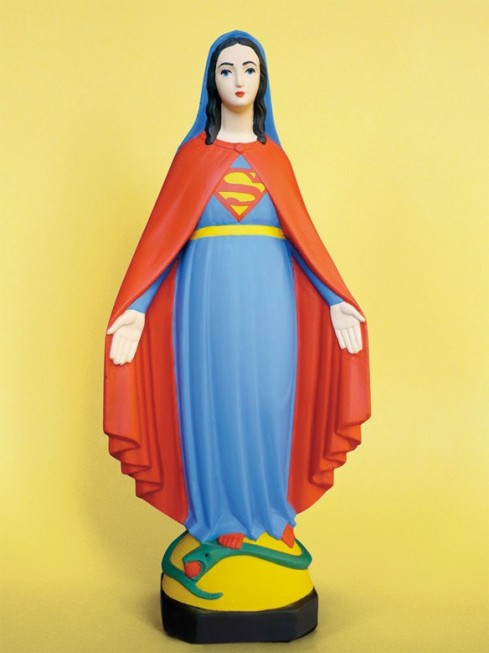

D’Amber was the closest thing I had found in Alice’s mental landscape to an icon of authority. I was getting nowhere by myself.

That still made it awkward to discuss with a stranger. My planned response to Alice’s need was unconventional and my credibility was in jeopardy if it became known that I was trying to get at Alice’s fixation by exposing her case to an outsider. After months, of treating her, it seemed to me that I could crack her resistance to taking my help if I could enlist D’Amber on my side.

Alice always spoke of the woman with intense admiration.

I tried to complete the picture for the financier, “You really have to do very little. For instance, if you could meet Alice here during one of our sessions and tell her that you and I have talked things over and that we are in agreement as to how to proceed. That would leave you out of any of the treatment and give me the mandate in her mind to allow access to her motivation. Of course, none of this would ever be discussed outside this office. Your part would be simply validating my expertise with Alice.” I crossed my fingers. Cracking Alice Roth’s case after two specialists had failed would be quite a coup.

“I don’t think so, Dr. Rand.” She shook her head.

Damn. What else could I say to get her to see this? I had tried to make it as easy as possible. “Alice will be disappointed.” I put plenty of emotion in my voice.

Suddenly, her chin came up. “I doubt that. To summarize what you are proposing; you’re acting for the court to try and normalize Alice’s behavior so that her husband and society can respect her once more. Yet her only crime is transforming her sexual privacy into public record. You want to do this by having me lie to her about my faith in your judgment. You don’t know me or my character, yet you’re willing to have me act as your leverage against your patient. You’ve hit an obstacle and rather than hard work, you’re looking for an easy answer and a quick fix from a complete stranger. Having tricked Alice into believing that I agree with the court, you’ll ‘take over’ and make her behave like a good girl. I must say I’m insulted you would propose such a thing.” She gave me an edgy look. “You must be quite the stuck-up elitist prig.”

I gaped at her. The calm and articulate delivery belied the venom of the words. She was like a restrained viper. Dangerous. She kept going on.

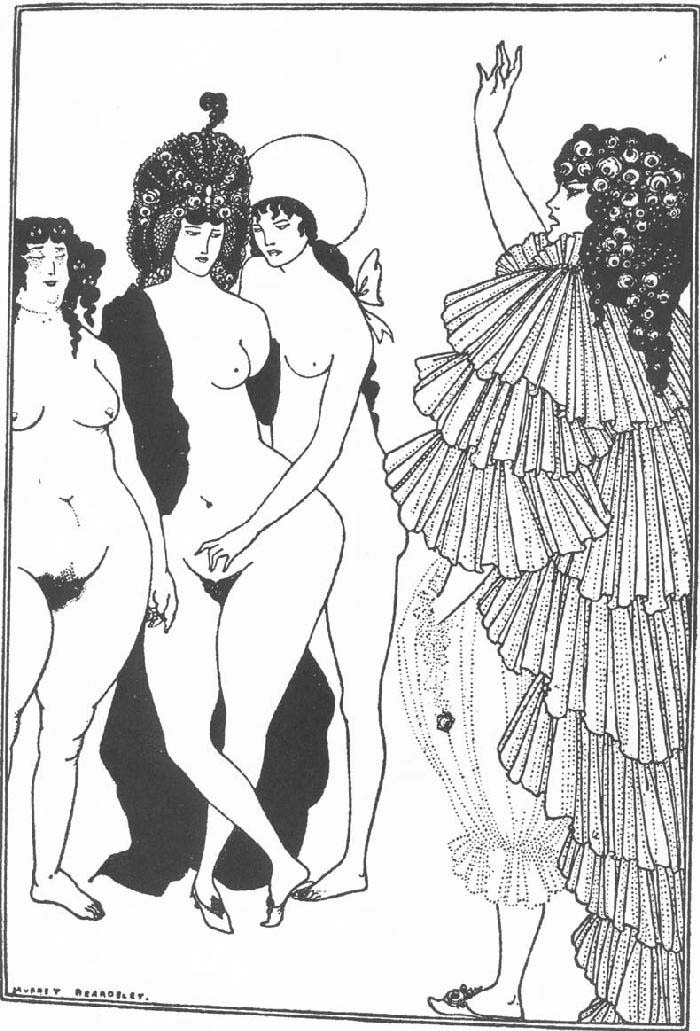

“A woman wants to show her breasts and paternal law says she’s mentally deranged? What about freedom of expression? What about art? A husband ignores his wife’s sexual tension for years and a woman psychiatrist rewards that by proposing theatrical therapy that will deceive the patient? Where is your feeling for Alice, doctor? I can no more validate your expertise than you can understand what dark things Alice has dared to look at in herself. Alice is a level beyond you that you do not understand. You are a child by comparison. My advice is loosen up, Dr. Rand.”

That was more than enough, I stood up. D’Amber was a nut case and this was a mistake. Worse. She was making me angry. “I feel we don’t have anything else to talk about then Ms. D’Amber. I will cure Alice without your help. I’m sorry your own problems have never been addressed in therapy. I won’t see you out or thank you for your time. Good day.” I went behind my desk without looking at her.

“Wrong again, Dr. Rand. You and I aren’t done.” There was humor in her voice, I glanced at her.

She sat there like a queen, staring right at me. There was something in her good eye that looked disturbingly like clinical detachment. I used to practice that in my mirror when I was in college. Fine. I’d just handle her with something she could understand. “We’re more than done, Ms. D’Amber. If you don’t leave my office immediately I’ll call for building security. I’m sure you don’t want that.” My ground and my rules bitch.

She studied me as if I was an interesting case. “You’ll find that the phone is temporarily out of order.” She casually laced her fingers on the leather arm of the chair.

Oh my god. She really was a nut. I picked up the phone, “Sorry. I’m not bluffing.” I didn’t even call my receptionist, I dialed 911 directly. Then I realized the phone was dead. Sweat beaded on the back of my neck. How could that be?

I tried to get a dial tone once more. I didn’t want to lose any momentum, I hung up and walked around her to the door.

She was still looking at the diplomas behind my desk. “The door mechanism is jammed. It won’t turn. You’ll also find that Della has gone to the ladies room, so even if you screamed at the soundproof door, there isn’t anyone on the other side to hear you.”

I froze with my hand near the door lever. Megalomania? If I grabbed it and it didn’t turn, she wouldn’t be a nut. I was very afraid of what that meant. If it did turn, I’d run down the hall until I found someone. It wasn’t safe here at all. I was scared to do either. I surprised myself by calling for my secretary without looking away from the handle that was two inches from my fingers, “Della!”

No answer. Ohmygod.

I tried the lever. Jammed. It didn’t turn at all. Cold sweat broke out along my back. I shivered and pushed the fear down and away, turned around and put the door to my back. I swallowed to steady my voice, assume the worst, assume she was psychotic, manipulate that aspect, stroke her, “I think we have misunderstood each other. Let’s start over.”

She turned around in the seat, smiling. Her hand went up, lifted her eye patch, ohmygod! there was———–.

—-Sex. Slutty outrageous sex. Making a public scene. Wearing slutty strap CFM heels to work. I never imagined how hot it might be. How I could ache for sex. You have to flaunt it when you want it that bad. Hot. Sweating. My crotch was getting soaked. Uncomfortable. I flushed with embarrassment. Corelle was going to make me over and display me like a prize cow. Bell collar. Brand on my ass. Black finger nail polish. Fingers playing with my pussy. I felt powerless. Malleable. So weak. So hot. The only things I could think about were my nipples and twat. Ugh, that word. Slutty. Twat. Hated that word. The sweat trickled down under my breasts. Tits. Boobs. If I took a step, I’d orgasm and never stop. Submissive. She had ruined me. A beast. A smart woman reduced to a fuck machine. I would look like a whore. Hot. So hard to fight. Hypnosis can not make you do anything you would not do while—–

An hour later, I was sitting on my desk edge when Della walked in. She gasped and put both her hands over her eyes. “Dr. Rand, I’m so sorry. I should have knocked. I didn’t—-” She turned around and rushed out.

So damn hot. Strange. It was quite a rush. Silly girl should have knocked. I pulled my hand out of my pantyhose and licked my fingers. The smell was so strong. I didn’t care for the taste. Was I actually hotter because she had seen me? I pushed my skirt back down and stood up. The slick sensation made me feel strange. Why had she thought she could just waltz in here? This was embarrassing.

How was I going to explain this? Should I try? Damn. She had interrupted before I could get myself off. I was still horny as a—. Well. No matter.

I went and sat down and pulled out the file on Alice Roth. Just thinking about Alice suddenly made me hotter than before. That was strange.

I pulled my skirt up and pushed my hand down into my pantyhose and started fingering myself. I’d have to convince Alice she was sick without D’Amber’s help.

* * *

A week later, the day’s case load was finished and Della came in and told me Ms. D’Amber was in the waiting room. My feet were hurting from the white strap sandal heels I had been wearing and I wasn’t in the best mood. “She has a lot of nerve not calling after ignoring our appointment last week. I suppose you should send her in, Della.”

“Doctor?” Della looked baffled. “But she did—”

“Did what?” I looked at her raising my eyebrows. “Tell her to come in. You can go. I’ll lock up.”

“Yes, Dr. Rand.” She went back through the door. She certainly looked confused about something.

Corelle D’Amber walked into my office without fanfare and I returned her firm handshake. Quick observations; she was average height with auburn hair, she seemed mid-thirties, but I knew she was ten years older than that. I had done extensive research on her in my plan to get her to help me crack the Roth case. She knew how to dress. Black leather pumps, no jewelry of any kind, and a black silk dress. The patch over her eye was exactly the same material as her dress, it gleamed from the soft light outside the windows.

I put aside the odd reaction that I didn’t want to talk to her. For some reason, it really bothered me that she had skipped our earlier meeting. I really needed her help to make Alice’s case another feather in my cap. Alice. Damn, why did I think of sex every time that woman came to mind?

I gestured, “Please take a seat, Ms. D’Amber. I’m so glad you could fit me into your schedule.” Hmm. That was a little too cold.

“Thank you, doctor. When we spoke on the phone, you sounded a bit desperate.” She eased herself into the maroon leather chair.

I had started to sit across from her, but her calm description of me as ‘desperate’ floored me. What in the world was she talking about? Desperate? “I assure you, my concerns are for a friend of yours. Someone I hope you are interested in helping.” I sat on the edge of the desk instead, letting my superior height give me an edge in the conversation. D’Amber was watching me closely.

Sitting there. I realized I was wet. I was aroused, but something felt wrong.

She pointed at my feet with her chin. “Nice shoes. Quite daring to wear white after Halloween. Don’t they hurt your feet? They look so high.” She looked up at me. I shivered. Why did this seem dangerous? Why did I buy these shoes? They hurt. They looked like shoes a hooker would wear. I looked down at them. Dark red nail polish, white hose, white straps pinching my toes and four inch heels. Tramp. My pussy was even hotter.

I had to say something. “Thank you. I like to surprise people.” I didn’t want to talk about my slutty shoes. It was too damn embarrassing to trade fashion tips with a self-made millionaire. “They don’t hurt at all. Latest thing.” God. That sounded lame. What a bitch she was. Why was I on the defensive?

The embarrassment ran through me like a river of fire. My underarms were suddenly soaked. I was flushed. Impossibly, I was very aroused. Today was not the day to talk to a stranger about Alice’s degrading sexual kinks. “I’m sorry you didn’t call last week to let me know you wouldn’t be coming. I’m afraid that I wasn’t expecting you at all. It just seemed you had changed your mind about coming. Maybe we should do this another day.” There, that should get her out of here.

“About coming? But I did come.” She smiled. Sweat broke out on my thighs. Something was terribly wrong. I squeezed my legs together. I was wet. Horny. I realized I was rubbing my backside on the desk edge and stopped. I stared at her. She was doing something. Had done something to me. She was here to do it again. I reached around for the phone.

When I picked it up, there was no dial tone. Then I remembered Della coming in the office last week after Corelle had left and finding me with my hand buried in my twat. Oh, that word was vulgar. I groaned and my pussy gushed thinking about Della’s expression. She saw me masturbating.

“Why don’t you turn around, Dr. Rand? Or should I call you Bess? The phone isn’t working.”

I put it down. My heart was pounding. I looked for anything heavy on the desk that I could use as a weapon. With a start, I remembered the small revolver in the bottom desk drawer. I had to get around the other side of the desk, keep her talking. “What have you done to me? What are you?” I did manage to get around to the side of the desk.

“Well, I don’t think you could understand what I really am. All I’ve done to you is give you some friendly advice. You didn’t have any respect for the dark things we all carry around with us, Bess. You were using Alice to make your own career. I decided to let you look at your own darkness. Loosen up.”

Loosen up? I was halfway around the desk. Loosen? Loose. Tramp. Whore. I didn’t want to turn around. If I did something terrible would happen. I couldn’t remember what but I knew not to look at her. No one can hypnotize you to do things that you wouldn’t do while conscious. Horribly, I turned to stare at her against my will. She stood up and smiled. Her hand went up, lifted her eye patch, ohmygod! there was—–

—-ohmygod. I was such a two-faced prig. I loved my wet pussy. I could admit that. Slutty sex. Public sex. Dark sex. All those true confessions. All those exciting clinical examples. Wearing Come Fuck Me heels all day. Staring men. Staring women. Dressing cheap. So hot. Aching. Wet. Horny. I got down on my knees before her. I knew I shouldn’t. I wasn’t a cow. Licking pussy on command. I didn’t want to be milked. Hot. Sweating. My crotch was so slick. Can’t stop. Mistress was going to make me over and display me like a prize cow. Bell collar. Black brand on my ass. Black finger nail polish like hooves. Fingers pulling my nipples, my pussy. Milk me. Malleable. So very hot. I realized I was licking her feet. God, it was so hot. So embarrassing. How could I be so slutty? My breasts hung down like small udders. The sweat trickled down my breasts. Tits. Jugs. I came when she tugged my nipples. I was like an animal. I was a—–

A nice morning. Della stopped when she walked in the office. “Dr. Rand?”

I looked up from sorting the mail. “Yes?” She had a half-smile on her face. It wasn’t flattering on her.

“Nothing,” she shook her head, still smiling, “there was a special delivery waiting for you in the mail this morning. Marked personal.” She set it down and went back to her desk.

Why did Della smiling at me make me so horny? That didn’t make sense. I picked up the package. Return address was my own street address. That made no sense at all. So disturbing. I didn’t remember sending myself a package. I opened it up.

Oh. I took the bottle out of the plastic bubble wrap. Black pearl nail polish. The color was so awful. Mindless Goth girls swam into my mind’s eye, all copying each other’s look. I opened it and painted over one finger nail with four strokes. My nipples ached. The color was really quite awful. I did another nail to see if it would look better. I couldn’t stop there. It was so stark. I was getting hot, just thinking about how noticeable it would be. People would stare.

Later, I took off my black fishnets so I could do my toes. When I was done, I couldn’t imagine why Della hadn’t chanced to interrupt me. I felt disappointed. I started playing with myself.

Oh. That was good. Visions of swollen tits and nipples spraying milk came to mind.

* * *

A week later, Della came in and told me Ms. D’Amber was in the waiting room. I flushed and my nipples started aching. “Tell her I’m not here. She can’t make appointments that we agree to, I don’t have to see her whenever she chooses to appear. Send her away, Della.”

“Doctor?” Della looked at me like I was speaking Swahili, “She’s been here twice before. You’ve been acting strangely, too. Are the two things connected?”

“I have?” I looked at her raising my eyebrows. “Such as?”

“Dr. Rand.” She hesitated, “You’re dressing oddly.”

I felt my pussy steam and instantly become slick. Della was insulting me? Criticizing me? God, that turned me on. “What do you mean, oddly,” I husked. Why hadn’t I worn panties this morning? My crotch was soaked.

“You’re wearing black polish and fishnet body stockings. A lot of your new blouses are really sheer. Your skirts are shorter than mine and you used to tell me to watch that. You said I looked unprofessional when I wore short skirts.” She paused, then rushed ahead, “Doctor, you’re dressing like a—.”

I bit my lip and came. The orgasm was horribly intense. She was telling me I was dressing like a young slut.

Corelle D’Amber walked into my office without fanfare and stopped. I came again when I saw her. She was breathtaking. Commanding. Della started to say something else, D’Amber looked at her and she stopped trying.

I put aside the instant reaction that I wanted to rub my crotch on D’Amber’s toes. I wanted to lie down on the floor and have D’Amber work her high-heeled toe between my legs. I was having some kind of breakdown. For some reason, this woman was a dream of realized domination and I wanted her to own me. Preferably right in front of Della. I was so hot now, that I could feel my thighs getting wet.

I whispered, “I’m so glad you could fit me into your schedule, Ms. D’Amber.” Hmm. What would she do to me now? “Don’t go, Della.” I was of two minds, one wanted sex and the other couldn’t think.

D’Amber looked at me, then back to Della, “How do you like the new Dr. Rand?”

“Just fine, ma’am,” Della lied with a false smile on her face. I came again. Oh, the hot shame. I wanted it again and again.

D’Amber walked over to me. She gave me a wolf’s smile. Hungry. She wasn’t human, I realized. How had I ever thought she was a human being? She was something older and more terrible. “Bessy, I don’t think you could stand another treatment. You’re ready now. She reached into her purse and pulled out a collar with a heavy bell on it. She started putting it around my neck.

The orgasms ran up and down my legs, my back, my nipples were so hot, I started pulling on them myself. “Moo,” I whispered.

Mistress D’Amber stepped away. Della stared at me in shock, her mouth an open oval. That was too much, I came again. “Moooooooooo.” I groaned.

“Della?” asked the Mistress. Della tore her eyes from me and looked at her. I could have told her not to.

Well. If I had really wanted to. I’m sure I could have.

Della and I spent the afternoon in intensely heated sex. She punished me. She milked me and told me what a little cow I was. She worked my pussy and ass with a strap-on I had bought some days before. She suggested I get a boob job so my udders would have some real heft. Of course, I agreed.

Of course, I would pay for it. Yes, I loved being banged by my secretary. Oh yes, I’d love to do housework. Yes, I was such a stuck up bitch. Oh, god. Everything was layers of heat and shame.

I came and came and came. It was so awful it was glorious.

Afterwards, I gave her a big raise.

* * *

Corelle D’Amber walked into her office and placed her purse on the mahogany desktop. The phone rang then, as if it knew when its mistress had returned and it could now deliver up its function and help her conduct business.

She eased it up to her ear, “Corelle here,” direct and to the point.

“Alice,” she smiled broadly, “how good to hear from you. Did you get the release from Dr. Rand? Everything signed and sealed? Good. No. That’s great, sweetheart. Glad to do it.”

She listened for a long time. “I’m afraid that’s true, Alice. None of this would have been a problem if Bill had stuck by you. I’m glad you realize that. He hasn’t been fair. He’s put you through a lot of hell.”

She nodded.

“Yes. Of course. You name the time and I’ll be there.” She lowered her voice, “Alice, you’re making the right decision. See you soon, sweetheart.”

Corelle put the phone down gently. She reached to her cheek and adjusted her eyepatch.

Then she smiled.