I first saw The Blair Witch Project when it came out, in the summer of 1999, in Summit, New Jersey, with my dad and one of my brothers in tow. The theater was sparsely filled, with no more than two other spectators. Of the three of us, I was the most eager to see it, being at once an avid fan of horror and a teenager all too easily susceptible to clever marketing, the unprecedentedly dedicated publicity rollout of this film’s benefactors being no exception. It was a short film, 77 minutes excluding the end credits. When it was over one of the spectators turned to my dad and said, “Now to go figure out what that was all about.” My dad shrugged in agreement. Genre films did nothing for him; he had fulfilled a parental obligation and quickly forgot what had happened.

I, on the other hand, could not forget. Quite frankly I was dazed and a bit shaken trying to piece together what I had just seen. I’ve had dreams like this, I thought, ones in which I found no exit no matter how far I ran, no shelter no matter how loudly I screamed, and cut off at the abrupt insistence of someone I could not see coming, though somehow knew was always there.

Eyes tend to roll to revelations like that, whether it’s the eyes of my dad towards me, of philistines towards snobs, or of film students towards everyone, and I can’t say I blame them. But it’s not an experience that anyone willfully avoids if it’s presented to them. Indeed, movie theaters and their unceasingly inflating admission charges have little other justification today. Some films enrapture us by their very nature and without proper consent. They have a way of upending logic and sense as viewers know them, and they don’t care to look away and don’t mind that they just dropped their last Sour Patch Kid. People who have seen, say, The Night of the Hunter, Blue Velvet, The Shining or The Room might be more inclined to agree with me. I have viewed The Blair Witch Project many times since it came out on VHS and cable, and now on instant streaming services. Whether it is the second viewing or the thirtieth, it is never quite like the first, but even so, the film’s initial hold has not let me go after all this time.

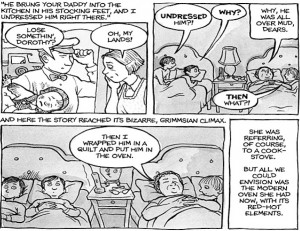

The Blair Witch Project is a film about a legend that has itself ascended into legend, its story and that of its creation and arrival are well-known even to those who haven’t seen it. In the mid-1990s, two young directors, Daniel Myrick and Eduardo Sánchez, had a clever idea of taking three unknown actors into the middle of the Maryland woods with two cameras, camping gear, and a loose script partly improvised by the actors, partly left for them piecemeal each day, while also rationing their food and depriving them of sleep. It told of three film students who went off to film a documentary about a local folktale only to disappear, leaving their unfinished film behind. Filming took eight days with an initial shooting budget of somewhere between $25,000 and $50,000.

It was not a new idea to anyone who has seen Cannibal Holocaust or the BBC’s War of the Worlds-style mockumentary Ghostwatch, but the film resonated, and profited. In its July 30 wide release it grossed nearly $30 million, placing it second in box office grosses that weekend, right behind Runaway Bride, and grossed $249 million worldwide. The film also polarized, and continues to do so. The Blair Witch Project currently holds a 6.4 rating on IMDB from 153,093 users and an average three out of five stars based on 1,921 reviews on Amazon. It is not hard to see why.

The film’s release was preceded by a hype effort that was an art unto itself. It included in-depth television documentaries and, most memorably at the time, a website, airing the possibility that the story was not fictional. They played on the film’s atmosphere, detailed the extensive background of the legend itself (the documentaries Curse of the Blair Witch and The Burkittsville 7 were so extensive they faked newsreel footage and other documentaries), while showing little of the actual film. But those looking for escapist schlock along the lines of The Haunting and Deep Blue Sea, both released earlier that summer, were doubtless disappointed by the film’s stark minimalism, its meandering pace, the grating agitation of the characters, scares that were at once too far apart and too subtle to be effective, and most of all the abrupt, ambiguous ending. “Where is the suspense? Where is the involvement? Where is the identification?” writes one IMDB reviewer. “The spectacle of three film-student types traipsing off cluelessly (sic) into an unfamiliar forest with a reported history of gruesome violence is just plain stupid.”

I would not put it past Artisan to have thought that they were releasing a gimmick film at the very least, one that would pay dividends either way, whether as a hyped flash-in-the pan or a low-simmering cult hit like Memento would be two years later. On the surface it would seem to have managed both. But the film’s unlikely lifespan past its own zeitgeist seems more than merely cultic.

The Blair Witch Project is one of those films to which simple appreciation is unsuited. It is a film designed for obsession. The obsession, however, is less about loving it or hating it profusely than it is about filling in its blanks or confronting what it already has to say head-on. The former is more prevalent, at least while it continues to be good business.

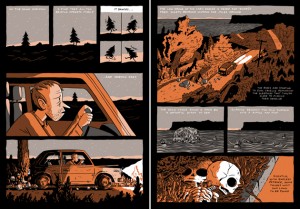

As the catalyst for the continuous deluge of “found footage” films, The Blair Witch Project is less an influence than it is a blank design template. Whether it is the big-budget disaster movie like Cloverfield, the real time noir of Catfish or Amber Alert, or the steady stream of low-budget indie horrors, which vary in quality from the clever Grave Encounters to the clumsy The Ridges, the objective is the same: to perfect its ancestor’s flaws while conceivably reaping its commercial success.

This is not to say that these films are bad, at least in isolation. Grave Encounters boasts a hackneyed asylum exploitation plot and scares that seem more artificial with successive viewings, but as a satire on paranormal reality shows—specifically Paranormal State—it is spot on. (Credit where it’s due, the very meta sequel is actually successful as a send-up to the abortive Book of Shadows: Blair Witch 2.) The V/H/S omnibus series offers the form in much shorter bursts, downplaying the tension and dead air with head-spinning—but no less self-aware—ridiculousness. Skew was made just as cheaply as Blair Witch, if not more so, but works its way to deeply troubling self-portrait of psychological tailspin. Perhaps the most complimentary Blair Witch descendent is Noroi (The Curse), a Japanese film released in 2005. Running at just under two hours, Noroi is perhaps the most overstuffed out of any of these films, and yet it is every bit as strange and engrossing as its predecessor, assuming the dimensions of a conspiracy film as much as a horror film, but defined every bit by its own world than by replicating and adding to a preexisting model. Amassed as one phenomenon, however, one gets a collective missing of the forest of the trees. Quite literally in this case.

The overriding complaint, whether from fans or filmmakers, is that the film simply didn’t work, let alone live up to its hype. The “less is more” approach to horror is nothing new, one need only recall producer Val Lewton, who helped turn a budgetary necessity into high art with films like Cat People. But in a period when gore effects were no longer much of a challenge or financial strain, Blair Witch seemed regressive. In truth, however, it was propulsive; in other words the film may just as easily have worked too well.

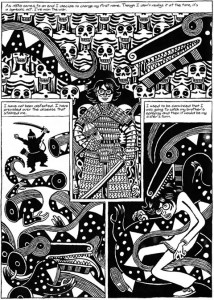

“If you’ve ever been camping in the woods,” Matthew Doberman wrote in his review of the film on AllMovie.com, “you know that a campfire’s light doesn’t reach more than a few feet into the darkness, but someone in that darkness can see you for a mile.” Ideally viewers are expected to relate to protagonists, otherwise what’s the point of horror? Yet that relation is often undercut by our remote viewpoint, sometimes voyeuristic, sometimes godlike. Indeed, Halloween literally opens with our view through Michael Myers’s eyes. Blair Witch forced that issue, putting us in the center of that darkness right alongside its doomed characters. How their experience is seen is changed; indeed, it is limited only to what they’re own senses detect, from the distant laughter of children to the directionless frenzy of the final minutes. That ending is important. Though bloodless and abrupt, its violence outstrips more gratuitous and iconic scenes of the decade—the ear scene in Reservoir Dogs, for instance—in stark brutality of purpose. The pointlessness of times spent yelling at people who don’t exist to “Just look behind you, shithead!” is laid conclusively bare. The film invites hate for ending without answers, but also for coldly reminding the audience that lives can end the same way.

The Blair Witch Project has not been immune to plaudits since its release, having been acknowledged as one of the best films of the ‘90s. Though its retrospective rankings—the 39th and 127th best film of its decade from The AV Club and Slant respectively—seem more obligatory than honorific. Horror films in general do seem sectioned off from greater zeitgeist acclaim, to be sure, but The Blair Witch Project seems more and more an odd film for its time regardless of genre. As we collectively struggle with ‘90s nostalgia, we are led to recall an aesthetically loud time. Tones were bright and warm, even if the working material was gruesome, attitudes were lightly ironic when they weren’t earnest but tended to give way to sort everything out neatly and calmly in the end. It was an endless summer at the End of History. Even Fargo, one of the coldest and most brutal films produced that decade, was a triumph of good over evil.

Standing in starkly athwart everything that preceded it, The Blair Witch Project was having none of it. Its tones were muted and damply autumnal when they weren’t entirely monochrome; and screen caps out of context make it barely distinguishable from a snuff film. Though it has a soundtrack, in the form of a character’s “mixtape,” filled with goth, industrial and post-punk jams, none of it was featured in the film. Hope gave way very quickly to confusion then to frenzy and then it ended. Cinematically, the film seemed poorly timed, coinciding with indie upstart fatigue wrought by films like Boondock Saints and Go. More broadly, however, it came just in time as the decade’s fatigue with itself was cresting. A period of economic optimism gave way to Y2K panic, school shooting panic, and a whole host of uncertainty waiting in the next decade. Just as Clueless, or even genre peer Scream, is the best film of the mid-‘90s, The Blair Witch Project was the best film of the end of the ‘90s.

The legacy of The Blair Witch Project is not altogether bereft of bright spots, however. For if it was too late for the 1990s, then it was too early for the 2000s.

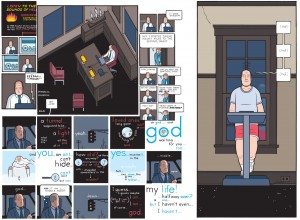

The internet of the late-1990s was very much the internet of marketing gurus, who perhaps saw Haxan’s and Artisan’s online rollout for The Blair Witch Project as the final frontier in taming the newfangled medium for their own purposes. Though it’s an early example of viral marketing, the website, relaunched on the film’s tenth anniversary, is less impressive now, especially in comparison to the revolution the film itself set in place.

Though the found footage trend as we know it wouldn’t come out for another decade with the release of Paranormal Activity, Blair Witch had an immediate effect on amateur filmmakers who wasted no time filming their own parodies. Three parodies I was able to find, the clever Wizard of Oz-inspired The Oz Witch Project and The Wicked Witch Project and the absurd Blair Warner Project, were all released in 1999 and can be viewed, appropriately enough, on YouTube. Perhaps its most fascinating, if indirect, descendent is the Slender Man, a uniquely 21st century folklore figure, a kind of urban legend as meme, incubated on message boards, crowdsourced and appropriated for fan fiction, visual art and film, and causing great controversy along the way.

This is not to say that The Blair Witch Project was a prophetic film; rather it was transitional, taking resources and measures already available and reapplying them wherever its makers’ limits and imaginations found agreement. What we have 15 years later is film that remains strikingly contemporary, especially compared to a film like The Cable Guy, released only three years before Blair Witch, which now looks hopelessly antique. To be sure, the film’s success hasn’t done its makers any substantial favors. Myrick and Sánchez have gone on to work separately, making mostly direct-to-DVD fare. Sánchez has recently taken up the found footage approach again with a contribution to V/H/S 2 and Exists, a Bigfoot movie seeing release this year. Its stars have been similarly low-profile since the film’s release, popping up in TV roles and other independent films. Heather Donahue, who won a Razzie for her performance, has since retired from acting to grow and advocate for medical marijuana.

The Blair Witch Project in the end is a one-hit wonder of sorts, though fitting to its other strange attributes it is a very rare kind that retains and acquires relevance over time rather than instantly depleting it.

_____

Chris Morgan is editor and co-publisher of

Biopsy magazine. He has previously written for The Los Angeles Review of Books and

The American Conservative, among other publications .