Friedrich Nietzsche’s alter ego, Zarathustra, answers: “A laughing-stock, a thing of shame.”

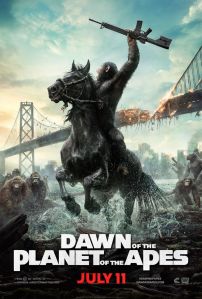

Chernin Entertainment and 20th Century Fox answer: “About $170 million.” That’s the budget for Dawn of the Planet of the Apes, almost double the price tag of its predecessor, Rise of the Planet of the Apes, which grossed $176M in 2011.

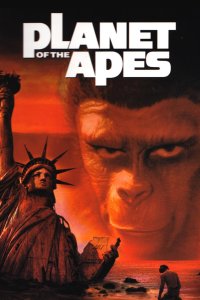

Or I should say its most immediate predecessor. The original Planet of the Apes was released in 1968 (with a quaint budget under $6M and gross of $26M). It was based on Pierre Boulle’s 1963 French novel La Planète des singes, but that’s not where the evolutionary ladder begins either.

Rise ends with mad scientist James Franco’s creation, a genetically altered super-ape, escaping to the wilds of the Redwood forest to father his own race. That’s how Victor Frankenstein’s creature wanted to end his origin story too. Either way, the creature is humanity’s first “arch-enemy,” the term he uses when Victor refuses to manufacture him a mate. The no-longer-mad doctor fears “a race of devils would be propagated upon the earth, who might make the very existence of the species of man a condition precarious and full of terror.”

Mary Shelley’s evolved imagination was pure fantasy in 1817, but Darwin made the terror real for Victorians. H. G. Wells named humanity’s predator the “Coming Beast,” describing “some now humble creature” that “Nature is, in unsuspected obscurity, equipping . . . with wider possibilities of appetite, endurance, or destruction, to rise in the fullness of time and sweep homo away.”

That fullness of time arrives regularly in Hollywood. If not apes, then zombies, aliens or androids are always propagating and making humanity’s condition precarious and terror filled. Some scientists take that last threat, the robopocalypse, seriously.

Cambridge’s Centre for the Study of Existential Risk worries about the evolutionary threat of artificial intelligence: “we risk yielding control over the planet to intelligences that are simply indifferent to us . . . just ask gorillas how it feels to compete for resources with the most intelligent species—the reason they are going extinct is not (on the whole) because humans are actively hostile towards them, but because we control the environment in ways that are detrimental to their continuing survival.”

That’s also the plot of Dawn of the Planet of the Apes. The super-virus that decimated the human population between films is one of those unintended consequences popular in mad scientist plots. Mira Sorvino accidentally breeds an army of six-foot cockroaches after ending a cockroach-spread epidemic in Mimic. Emma Thompson cures cancer in I Am Legend, and next thing vampires rule Manhattan. James Franco’s genetic tampering would have turned everyone into super-geniuses. Or at least everyone who could afford his corporation’s new designer drug. If they’d had a chance to market it, the sequel would have been called Rise of the Planet of the Ubermensch.

No new breed ever cares about its predecessor. “And just the same shall man be to the Superman,” continues Zarathustra, “a laughing-stock, a thing of shame.” And yet Superman and his species of superheroes were born to battle such Coming Beasts. The Fantastic Four kept a subterranean world of monsters from rising up in their first issue. Atlanteans would have swept humanity away if the Human Torch hadn’t doused Namor’s Golden Age attacks. Blade is still staunching the destructive appetites of our vampire competitors. Every comic book is a survival of the fittest, ending with a superman at the top of the food chain.

But screenwriters Mark Bomback, Rick Jaffa and Amanda Silver include no super-saviors in Dawn. The hero type is usually a literal or metaphorical cross-breed who absorbs the threat of the racial other and reverses it to save humanity. Thus cyborg Arnold Schwarzenegger thwarts Skynet, and the Man of Steel thwarts General Zod’s Kryptonian invasion. Dawn would need an ape-man like Tarzan, but instead it’s the super-ape Caesar who was raised by humans and saves his people from us.

Which is a pretty compelling reversal of the formula. The supervillain is Koba, an ape so scared (literally and metaphorically) by humans that his hatred turns him into one. By the end, Caesar says he’s no longer an ape. He’s been completely absorbed by human hatred.

But there’s one flaw in the film’s evolutionary theory. It could have been titled Dawn of the Planet of the Patriarchy. I understand that actual ape culture is male-dominated, but these are scifi apes. They can talk and drive tanks. Surely there’s room for females somewhere in the hierarchy. The lone female ape character, Caesar’s jewelry-wearing wife, lies around giving birth and needing antibiotics. But would every female uber-ape accept the role of stay-at-home mom while the males go off to war?

The human cast is worse. Keri Russell, the lone female Home sapiens character, spends the movie saying things like, “I should come along in case someone gets hurt and needs a nurse!” She also prepares and serves food for her male campers. I was a part-time stay-at-home dad for years and still do a share of cooking and Band-Aid applying for my campers. But if faced with an ape-ocalypse, my wife and I would divvy up the guns too.

No intelligent species can ignore the skill sets of half its population. Not if the species wants to survive. And the humans in Dawn won’t. If you missed the first movie, there was a brief mention of a space mission to Mars. Those astronauts are scheduled to return (minus Charlton Heston) in July 2016, and I think we all know what Darwin is plotting for them.