You come across it while cleaning out your attic: a book, a CD, a VHS cassette.

My God, you think, that was one hell of a novel/song/movie! Nostalgia mixes with anticipation as you prepare to savor it anew.

But what’s this? It seems to have gone rotten! Phaughhh! Retch! Ptooey!

How on earth were you ever taken in those long years ago by this foulness that sucks like an electrolux? Was your taste that abysmal?

Worry not. You are the latest victim of a virulent virtual vampire: the Suck Fairy.

Jo Walton revealed all about the little monster in a blog post on Tor.com. Go read the whole thing (and the many comments that amplify it); this extract gives us the gist of her warning to mankind:

The Suck Fairy is an artefact of re-reading. If you read a book for the first time and it sucks, it’s nothing to do with her. It just sucks. Some books do. The Suck Fairy comes in when you come back to a book that you liked when you read it before, and on re-reading—well, it sucks. You can say that you have changed, you can hit your forehead dramatically and ask yourself how you could possibly have missed the suckiness the first time—or you can say that the Suck Fairy has been through while the book was sitting on the shelf and inserted the suck. The longer the book has been on the shelf unread, the more time she’s had to get into it.

I, too, have suffered her bite. The superhero comics I loved as a child count some of her sorriest victims.

These old comics I class into four categories.

The first comprises work that still holds up, mellowed like old port. Examples would include Ditko and Lee‘s Spider-Man, Kirby and Lee’s Fantastic Four and Thor; though I prize them more now for qualities less appreciated by a child, notably humor.

The next category covers those comics that only interest me through nostalgia, or that tickle my camp funny bone, or that still please me for purely formal reasons such as good draftsmanship: 1960s Curt Swan-drawn Superman, Steranko‘s S.H.I.E.L.D, Gil Kane’s Green Lantern.

A third category consists of work that simply disappoints today, with no strong redeeming features, entertaining enough for a young boy but without interest for the adult me; say, Sal Buscema-drawn Marvel Team-Up.

And then, the dread fourth category:

The Spawn of the Suck Fairy.

Suck Fairies casting their curses at ComicCon

My library recently acquired a copy of Marvel’s Essential Iron Man, part of that publisher’s welcome line of cheap, phone-book sized black-and-white reprints.

I decided to check out the strips I so enjoyed at age eleven.

Cover art by Bruce Timm

Oh, dear God in Heaven. Zut alors.

After reading a few stories, I felt like gouging my eyes out. That fey bitch had infected every single page with suckiness of a cosmic level.

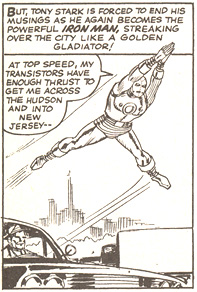

Ahhh, shut the “!@#§!* up. Take the Holland Tunnel like everyone else, you douche. Art by Don Heck.

I was mystified by how sucky this printed turd was.

I mean, I certainly have a high tolerance for mediocre comics. Here was far from the worst comics art I’d ever seen. (The most atrocious story in the collection isn’t drawn by the series’ regular, the oft-derided Don Heck, but by the excellent Steve Ditko. Actually, Heck’s art was better than I remembered.)

The scripts were probably no more moronic ( with their Cold War Commie-bashing and brainless plots) than other non-sucky comics of the time (the mid-60s).

Well, thank you, Ms Walton, for revealing the culprit: the Suck Fairy.

How that destructive little vermin has blighted literature — blighted my most precious books!

When I was 12, in 1966, I had just finished reading The Lord of the Rings, by J.R.R Tolkien. I lived that book as one can only at that age.

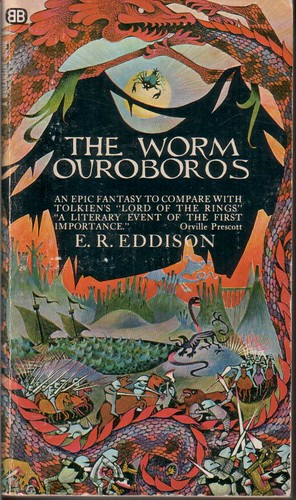

I was jonesing for more, and Ballantine Books (Tolkien’s publisher) was canny enough to offer me the following:

The Worm Ouroboros is an odd duck of a novel.

Written in 1922 by E.R. Eddison (1882–1945), it chronicles the war between Demonland and Witchland on the planet Mercury. Its prose style is a pastiche of Jacobean writing, gorged with archaism that I found near-impenetrable; but I doggedly forged on with frequent recourse to a dictionary, much to the improvement of my vocabulary:

But a great wonder of this chamber, and a marvel to behold, was how the capital of every one of the four-and-twenty pillars was hewn from a single precious stone, carved by the hand of some sculptor of long ago into the living form of a monster: here was a harpy with screaming mouth, so wondrously cut in ochre-tinted jade it was a marvel to hear no scream from her: here in wine-yellow topaz a flying fire-drake: there a cockatrice made of a single ruby: there a star sapphire the colour of moonlight, cut for a cyclops, so that the rays of the star trembled from his single eye: salamanders, mermaids, chimaeras, wild men o’ the woods, leviathans, all hewn from faultless gems, thrice the bulk of a big man’s body, velvet-dark sapphires, crystolite, beryl, amethyst, and the yellow zircon that is like transparent gold.

The book enthralled me.

Jump forward ten years to 1976. I was 22, doing my military service after three years of university, and I picked the book up again. This time I found it easily readable, but rather slight; an enjoyable fantasy.

Cut to the year 2006. Once again, I plunged into the Worm — and stopped after 50 pages. Her Dread Suckiness had struck again. The book was now a plodding, cardboard-thin gallimaufry of tushery, Wardour Street pretentiousness and outright plagiarism.

“Yet, lo,” she said, as a sweet and wild music stole on the ear, and the guests turned towards the dais, and the hangings parted, “at last, the triple lordship of Demonland! Strike softly, music: smile, Fates, on this festal day! Joy and safe days shine for this world and Demonland! Turn thy gaze first on him who walks in majesty in the midst, his tunic of olive-green velvet ornamented with devices of hidden meaning in thread of gold and beads of chrysolite. Mark how the buskins, clasping his stalwart calves, glitter with gold and amber. Mark the dusky cloak streamed with gold and lined with blood-red silk: a charmed cloak, made by the sylphs in forgotten days, bringing good hap to the wearer, so he be true of heart and no dastard.

Thou suckest, o purple prose. Fie upon thee, sirrah!

(Ah, well, at least the illustrations remain lovely. Here are the Lords of Demonland:)

Art by Keith Henderson

The King of Witchland conjures diabolic forces: art by Keith Henderson

To be fair, over the end of the ’60s and the first half of the ’70s, Ballantine Books (thanks to their crackerjack editor Lin Carter) revived many wonderful classics of fantasy in paperback: Hope Mirlees‘ Lud-in-the-Mist, James Branch Cabell‘s Jurgen, Lord Dunsany‘s The King of Elfland’s Daughter, William Hope Hodgson‘s The House on the Borderland and The Boats of the Glen Carrig… all masterpieces immune to the Suck Fairy’s kiss!

(Touch wood…)

I used to re-read The Lord of the Rings every five years , but haven’t done so for the last two decades; you can guess why I am afraid to.

But the Suck Fairy’s master-stroke was her demolition of one of my most cherished loves:

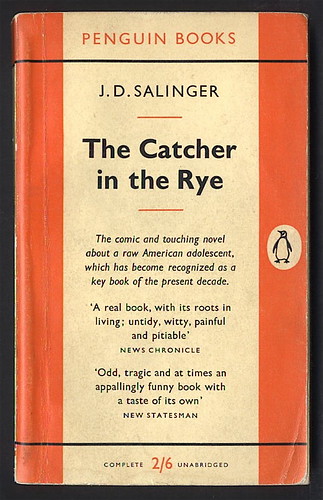

Like millions of 16-year-olds before and after me, I read J.D.Salinger‘s novel The Catcher in the Rye and knew– KNEW!– that it was about me, me, ME; its hero, young Holden Caulfield, was me.

All my adolescent longings and heartache and rage against the goddam phonies of the grown-up world were here. I fell in love with a book.

But the Suck Fairy was lurking, biding its time with demonic patience.

J.D.Salinger

I next read Catcher when I was 34.

I was repelled and enraged.

That little preppy brat Holden– I’d kick his snotty rich-kid ass all over Manhattan.

What a nasty, arch, supercilious volume of egotistic peacockery– compounding its silver-spoon ugliness with a bathetic display of mawkish sentimentality.

Damn you, Suck Fairy! Leave me alone with my illusions and my bottle.

*********************************

David L. Ulin, in his reflective essay-book The Lost Art of Reading, is troubled by this phenomenon:

I had lost books by rereading them. Flannery O’Connor’s Wise Blood, for instance, which I had loved in college but not so much later, when I began to see it as a young writer’s pastiche, less about life as it really is than a naïf’s projection about how life might be.

He is afraid to reread The Great Gatsby– and is relieved to find it as superb as he’d remembered. (I, too, find Gatsby to be better at each fresh reading.)

He finds a possible explanation in Anne Fadiman’s 2005 book Rereadings:

The former [reading] had more velocity; the latter [rereading] had more depth. The former shut out the world in order to focus on the story; the latter dragged in the world in order to assess the story. The former was more fun; the latter was more cynical. But what was remarkable about the latter was that it contained the former: even while, as with the upper half of a set of bifocals, I saw the book through the complicated lens of adulthood, I also saw it through the memory of the first time I’d read it.

Anne, Anne, Anne… that’s all true, all very well and good…

…but it doesn’t protect your literary treasures against the relentless despoiling of the vile, gloating Suck Fairy.

Is there no hope, then? As we all age, our personal troves of culture age, too.

And the evil Suck Fairy grows mightier.

Yet… is she so wicked? Doesn’t she serve an essential function in our intellectual ecology…culling the herds?

Let’s end with the heartening words of Demetrios X, commenting on Ms Walton’s blog:

There is also an extremely rare counterpart to the Suck Fairy, the Anti-Suck Fairy. It’s only happened once or twice, but I have encountered books that I was very disappointed in the first time I read them, and then found I quite liked them on a second reading. That’s not a matter of growing up or being older either. It’s happened to me with books I’ve read as an adult with a gap of only a few years.

Yes, indeed. The Suck Fairy and the Anti-Suck Fairy are locked in constant struggle, and in the course of a reader’s life may, turn by turn, conquer a book.

Suck and Anti-Suck, in gentler days before their all-out war

Like so many children, I was enamoured of L.Frank Baum‘s Oz books.

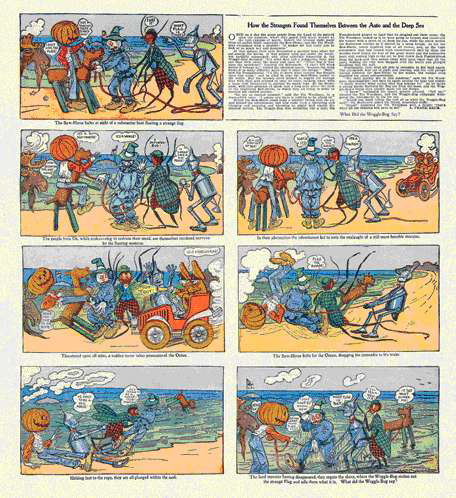

An Oz comic strip by its original illustrator, W.W.Denslow

But as an adult, I put them behind me, finding in their simple prose little of the cleverness and charm that keeps Alice in Wonderland or the nonsense verse of Edward Lear so beguiling to grown-ups.

But the Anti-Suck Fairy was on the job! Now I delight again in the Oz books, discerning satire and shrewd political commentary behind the fairy-tale façade.

Likewise, the Edgar Rice Burroughs books I devoured as a teenager seemed unreadable in later life; tedious, racist hackwork.

Art by Frank Frazetta

But good ol’ Anti-Suck showed me the wit and liveliness that ERB masters at his best.

I particularly recommend Carson of Venus and Tarzan and the Lion Man. Among other pleasures: the former for its sly attack on eugenicism, the latter for its genial self-parody and savage send-up of Hollywood.

Time to give Catcher in the Rye another go? You bet!

So take heart, my fellow culture vultures, the S.F. is not invincible.

Can you tell me of your own encounters with the Suck and Anti-Suck fairies in the comments below?