W.A.S.P. Thanksgiving

Redneck Thanksgiving

Animated Thanksgiving Continue reading

Fusanosuke Inariya, 2010, Digital Manga Publishing and Oakla

I’d heard very, very good things about this manga from people who were hoping someone would pick it up from licensing limbo. Now that June has come to the rescue, I decided I could not ignore all the buzz about this title, despite my misgivings. Grave misgivings. Because look at that cover. I am merely talking about my own squick factors here, but even a whiff of WW II fetishization raises a forest of red flags for me. I am also not a fan of ukes who appear to be under age. (Or semes either, but putting the too-young-looking one on the bottom seems to bother me more.)

Now, Taki, the uke of whom we speak, is younger than the seme, but not under age. It’s just that in the very fully realized sex scenes, he looks it. He’s even in a position of great power, a lord and a military commander. Not underage, not powerless. This is so clear that by the end of the book, I almost got over thinking he looked twelve whenever he was stripped (which was often). It is a testament to the power of the story-telling here that I was pretty much able to get over my pretty thoroughgoing distaste for this kind of visual.

And the book is about war. Old-fashioned world war, including lots of old-fashioned ideas about heroism and honor and noblesse oblige, all of which I think is not only horse shit, but dangerous nationalistic horse shit. I do not find war stories romantic. And I especially worry about the kind of sexual excitement some people get from fascism, often symbolized by Axis uniforms. Now, just like the uke isn’t actually under age in this book, the war isn’t exactly WW II, and the lovers (Klaus, a tall, strapping blond, and Taki, a diminutive Asian man) aren’t exactly German and Japanese. The particulars are technically different, but – look at the cover. It’s obvious what we’re looking at. I do not like to take things too seriously, especially yaoi manga, of all things, but I was highly skeptical that I was going to be able to enjoy a manga in this setting. (Apparently even Kinukitty has limits.)

But I was told no, it’s OK, really. It’s well done. I didn’t think that was likely, but I was interested in what this book would be, anyway, so I bought it. And pointedly ignored it for months, unable to quite deal with it.

I wound up bringing it with me to the park to read while my son flung himself alarmingly off large pieces of playground equipment. I will point out one thing right now – this is not the book you should bring with you to the playground. There is lots of graphic sex. Lots. Graphic. I was off in a corner by myself, but I kept looking furtively over my shoulder, terrified some other, more responsible parent would show up and see this extremely NSFW image after the jump:

Bliss was it to be alive in that dawn,

But to be young was very heaven!

—Wordsworth

A house in Launceston Place, Kensington, London; we were a couple of doors down.

In 1969, my family moved to London; in December of that year, I turned 15.

London– 1969– 15 years old?

Yesss!!!!

“Swinging London” was still very much roaring along. Behold Carnaby Street, luv:

I’d come from a deeply repressive Swiss all-boy Jesuit school the year before, where tracts against masturbation were solemnly handed out, and attending a party featuring ‘impure’ pop music was grounds for expulsion.

And here– just in time for my puberty– was I introduced to this carnival, this opportunity to blossom!

Soon I’d ditched my staid flannel tartans and chino trousers for paisley scarves, ruffled pink shirts, and bell-bottom pants…

That’s me, age sixteen, literally rising above my peers at school.

The Beatles, Led Zeppelin, Jimi Hendrix (who died in the hospital next door to our first house — for some reason that spooked me at the time), The Mothers of Invention, The Rolling Stones…they furnished the soundtrack to my life.

Ah, but this is a column about comics, is it not? So what was the scene like at the dawn of the ’70s?

It was glorious.

Current wisdom holds that comics of the ’70’s were in a particularly dire patch of their history; but this sad state of affairs came about essentially after 1973, and there were bright spots even so until the end of the decade.

The comics Underground was at the apex of its short history; Crumb, Shelton, Deitch and co. Their comics were hard, but not impossible, to find in London; generally in the funkier record shops like Cheapo Cheapo Records off Picadilly, or in the patchouli-scented head shops.

Mostly, though, they were reprinted in underground newspapers like the International Times (IT):

click image to enlarge

The British Underground comics scene was pretty underdeveloped, though there were promising exceptions. Here, from IT, is Michael Moorcock‘s Jerry Cornelius, as rendered by Mal Dean:

click image to enlarge

An all-comics offshoot of IT was Nasty Tales, edited by the musician Mick Farren. More Crumb than you can shake a stick at:

… and it was a Crumb spread of an orgy that caused the publisher to be prosecuted in the sensationalised trial that set a precedent for freedom of the press. A benefit comic was published, with early work by Dave Gibbon:

Meanwhile, across the Channel, French comics were enjoying something of a golden age; magazines such as Pilote and Charlie were moving to more adult content.

That 1969 Christmas, my father gave me a book that was a touchstone for an entire generation of fans: The Penguin Book of Comics, by George Perry and Alan Aldridge:

My collecting centered mostly on the American mainstream: Marvel, DC, Warren.

At first, American comics were distributed in the UK in a very haphazard manner.

They were mostly unsold copies from the USA that were shipped across the Atlantic as ballast. You never knew what you’d find: that ensured the thrill of the hunt all collectors know.

It was a rich period in the mainstream. The old-guard cartoonists– Kirby, Adams,Wood, Severin, Kubert, Heath, Kane and so on– were at the top of their powers, and were joined by a crew of young Turks of remarkable talent– Barry Smith, Mike Kaluta, Berni Wrightson, Frank Brunner, Ralph Reese, Howard Chaykin.

Popular genres other than the super-hero were still flourishing: war, mystery/horror, romance, fantasy. There was still a plethora of humor books.

And an innovation that foretold the future of comics as we know it was coming into being: the comics shop.

click image to enlarge

When I first opened the door of ‘Dark They Were and Golden-Eyed’, Britain’s first comics store, I thought I’d died and gone to heaven. A shop given over entirely to comics? Was it possible? Was it even legal? It was indeed.

Derek ‘Bram’ Stokes and Diane Lister…for ten years the priests of London’s comics temple

And for the first time, I was meeting other comics lovers there: I had discovered fandom. And with fandom, fan publishing.

In those pre-Internet days the main medium of communication for comics lovers was the fanzine. Britain had its fair share of ‘zines, such as Rich Burton’s Comic Media News or Frank Dobson’s and Dez Skinn’s Fantasy Advertiser.

Yes, breathes there a fan with soul so dead that to himself has never said, ‘I think I’ll start a little fanzine’?

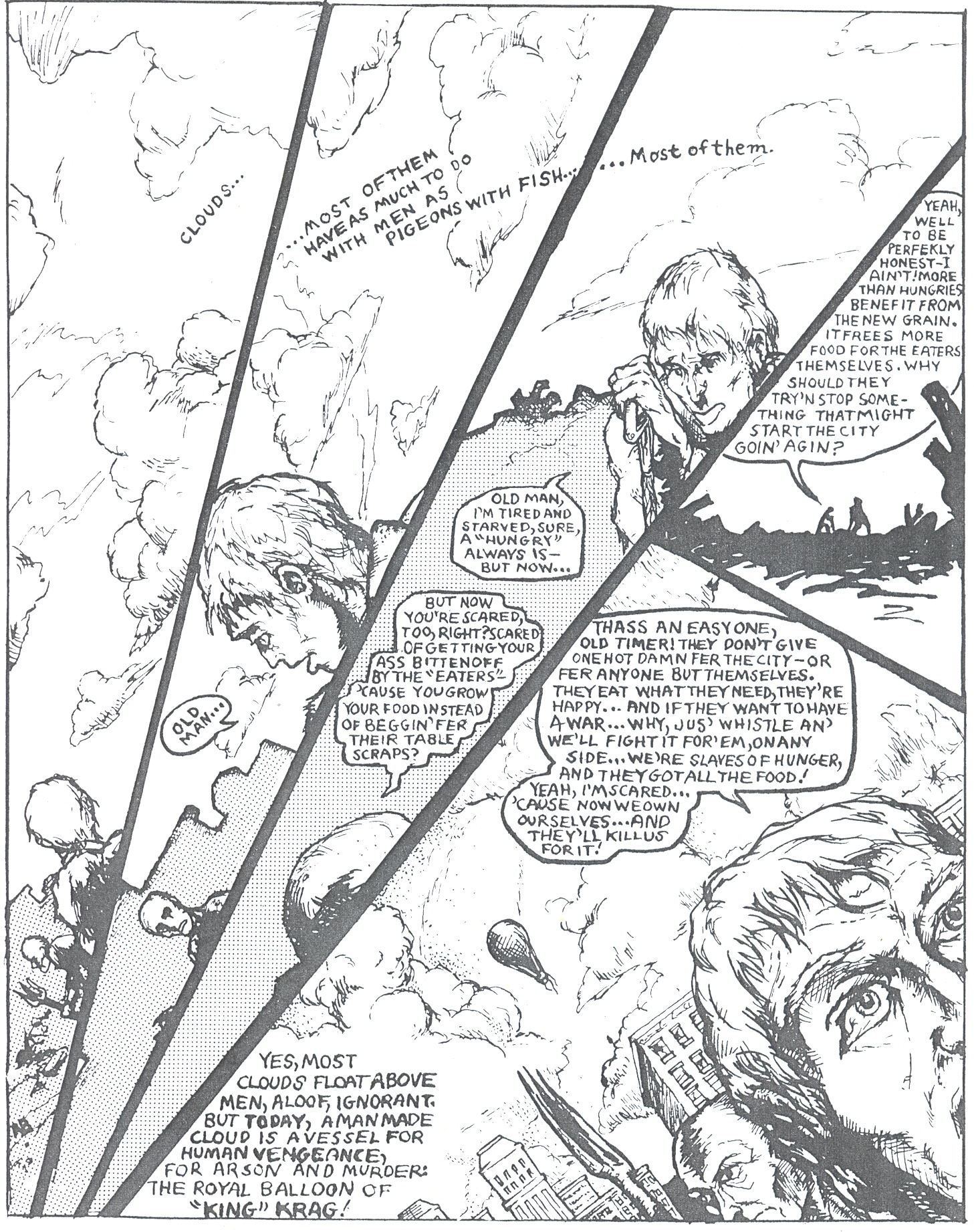

And indeed that was my thinking when, aged sixteen, I started drawing a comic strip with the alliterative title ‘King Krag.’

Now, printing options were fairly limited in those days. Mimeograph was still widespread; photocopies were becoming available, but they couldn’t reproduce solid blacks and needed a special paper. Offset printing was expensive.

This last limitation, though, was swept away by a new business model. The Instantprint chain offered printing in small runs at a reasonable price. Not free, though, and I struggled to get together the twenty-five pounds needed for a print run of 200 fifteen-page pamphlets.

I took a decision that I regretted deeply at the time: I sold most of my comics collection.

In retrospect, I’m very glad I did. It broke the anally-retentive hold collecting had on me: thenceforth I would buy to read only. I would no longer obsess about completing runs of series and throw away money on stuff I didn’t even like to close gaps in my collection.

I teamed up with my friend Ahmed Sehrawry, who took the impressive title of Managing Editor; really, I just wanted someone to talk to– I did all the actual work. Another friend, Chris Lomax, provided the strange back-up strip ‘Milkman.’

I drew the strip same-sized (A5). Never again. You don’t save any time. In fact, the six pages took me over a year to finish.

I remember bringing the package of printed pages back to my school — the French Lycée in London — to the art department, where my art teacher gave me a room and a bunch of tables: yes, we were collating and stapling by hand– we couldn’t afford machine collation or binding. No worries, my friends and I had a good time; a collation party is much like a corn-shucking bee, an undemanding communal activity, interrupted by the odd tea break.

(Tea is one addiction I picked up in England.)

By God, the first time you see your work in mass reproduction is a trip and a half! And the first copy of a finished work…does that feel good in your hands.

I was seventeen and a publisher.

Now, I will beg your indulgence for the artwork shown. It was produced by an immature young fellow who wore his influences all too prominently; I’m harder on that boy than you could ever be. Still, as an artifact of a past 38 years gone, it repays arm-length study. Here is the cover of Bizarro #1:

What strikes the 55-year-old me about the seventeen-year-old me’s drawing above is the level of violence. True, the culture was moving that way; this was the age of films like The Wild Bunch, Straw Dogs and A Clockwork Orange. But looking at that cover, I can only ask in dismay: was I that full of incoherent rage? More than another typical teenager? Apparently, yes.

Influences are embarrassingly obvious: Frank Frazetta, Barry Smith. A less obvious influence is Géricault‘s Le Radeau de la Méduse:

…which explains why so many of the figures therein rudely turn their back on the reader.

Also irritating are the visual tics picked up from Berni Wrightson: the ‘saliva ropes’ in the shouting character’s mouth, the ‘twisty hair’ on his forearms.

Note the patterned background: I had just discovered Letratone, and like so many neophytes was inclined to abuse it, as the luckless readers of this blog shall soon confirm.

On the plus side, the composition holds together fairly well (you can’t go far wrong with triangles) and there’s a real sense of depth.

But that sloppy logo is unforgiveable.

On to the strip. It’s a nightmare of incompetence.

Note on this splash page how I avoided heavy blacks: at that time, I was intending to produce this via photocopy.

Apparently, in the year 2025, for some reason they revived flintlock muskets…

It’s the standard post-apocalyptic fun future, inspired by Roger Zelazney‘s novel Damnation Alley and, oddly, Jack Kirby’s early Jimmy Olson comics. A bit over-tidy for after the apocalypse

I’m surprised to see how competent the perspective is: I don’t recall having studied perspective at that age (16), but I guess I had.

I’m afraid lousy dialogue and worse lettering are the hallmarks of my writing here. I was a nice white middle-class boy, so of course I tried to talk tough. Guns are by definition cool at that age.

Not the fishbowl-lens perspective on the guy’s hand in panel two. I was probably imitating Neal Adams.

The fussy, unnecessarily confusing odd panel shape was a disease of the time. I guess I was following in the footsteps of Jim Steranko and of Neal Adams. Note the last panel: you won’t see another woman in this macho world for macho men.

More weird layouts, odd angles, arbitrary cropping. The guy walking downstairs looks like he’s about to fall on his hairy face. I learnt that the real challenge in drawing isn’t in detailing giant space armadas– it’s in showing someone walking downstairs or opening a door.

So endeth chapter one.

There followed a mimeographed page of messages from the editor. I’m relieved to note that neither Ahmed nor I took himself very seriously. It was typewritten: word processors didn’t exist, and typesetting was expensive.

Rounding out the book was Chris Lomax’s ‘Milkman’. Its primitivism and absurdity have stood the test of time better than my overblown strip. Chris went on to be a successful stage and set designer in Paris, working on films such as Betty Blue.

We return to the horrors of mimeograph. Bram at ‘Dark they Were and Golden-Eyed’ let us drop off some copies on consignment if we’d run a free ad for his shop.

Well, Bram, you get what you pay for. And this is what ‘free’ pays for:

Ahmed took fifty copies to sell at his school; I took the remaining hundred and fifty to sell in mine. I recruited my brothers Philippe and Gérard, as well as friends like fellow comics- fan Sanjit, to spread out through the school and tout my inky baby.

We sold out within 24 hours.

It seems that publishing a comic in high school is like giving a rock concert in the gym or acting in the school play. The kids’ll support you just because you’re one of them. (Our principal was something of an arsehole about it, as I hadn’t asked for his permission; fuggim, I was out of there anyway.)

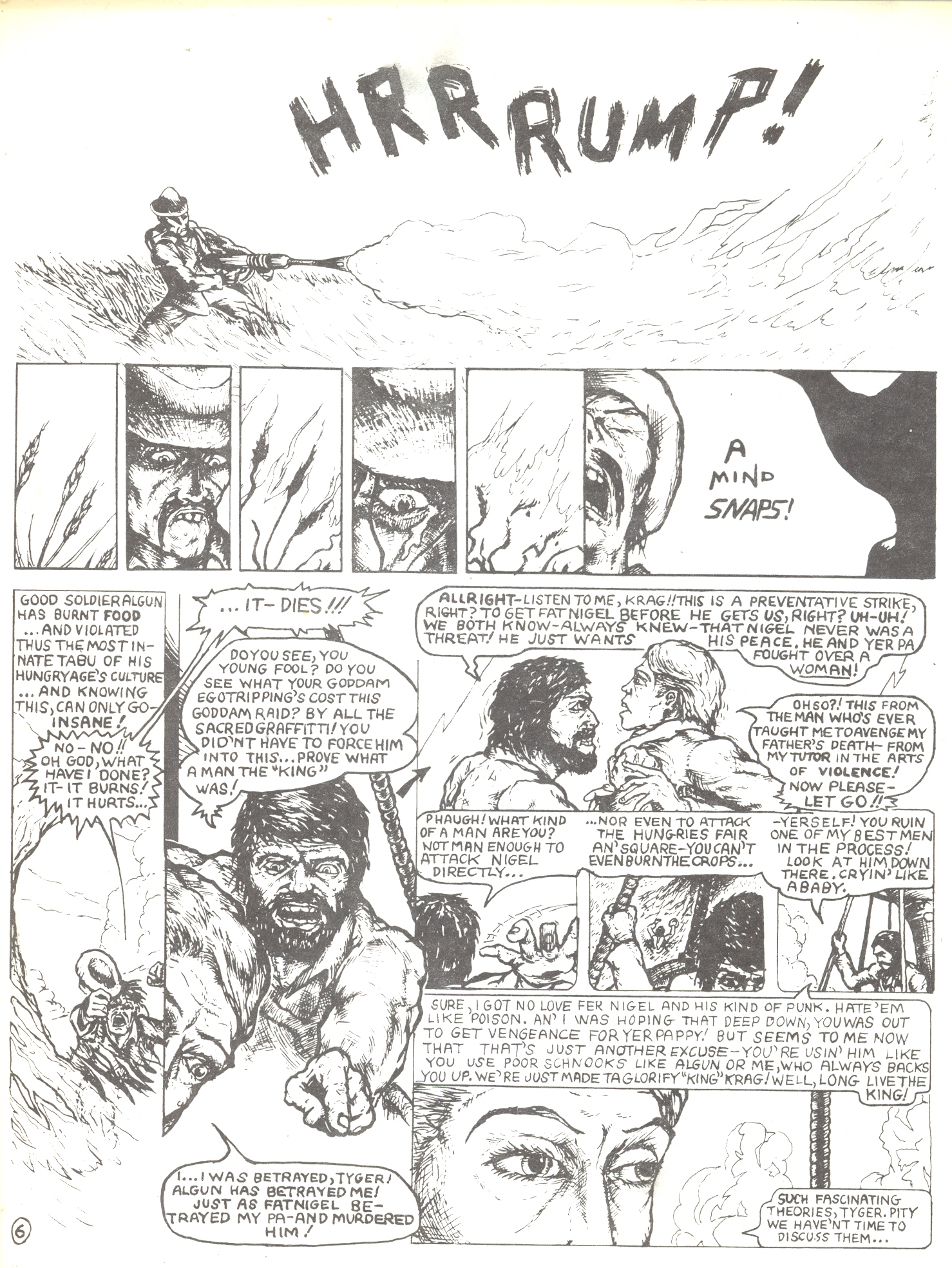

Issue 2 came out over a year and a half later. Now I’m a terribly slow artist, but this was ridiculous.

I had gone to Paris to study art at the Faculté des Arts Plastiques et des Sciences de l’Art of the Sorbonne. I was studying electro-acoustic music under Yannis Xenakis, screenwriting under Eric Rohmer, conceptual art under Journiac, comics under Jean-Claude Mézières.

I had outgrown my adolescent strip. It frankly embarrassed me.

Why didn’t I just give it up, then? A misplaced puritanism– I had vowed to break my bad habit of starting projects and not ending them; and I didn’t want to let Ahmed down.

The second issue boasted another odd cover, replete with clichés taken from Frazetta, Ploog, and Gustave Doré. I like the poor sap in the foreground’s expression. “I gotta turn around…but I really don’t wanna turn around…but I gotta…”:

Page one– more arbitrary panel noodling, fatuous captions, and peasants dutifully giving us an “infodump”: a massive exposition of stuff they already know and shouldn’t be repeating.

God, the inflation of those speech balloons.

More gratuitous violence follows. (I give myself some credit for actually researching hot-air balloons.)

From here to the end, you’ll note that the panel-per-page ratio goes up, to as much as fifteen. Was this innovative structuring for more intense beats? No, it was bad planning. I leave the rest of the story to the masochistic blogreader. It depresses me to read it myself.

For the second issue I had simply mailed the pages to Ahmed in London and let him do it all himself. A bit cowardly of me.

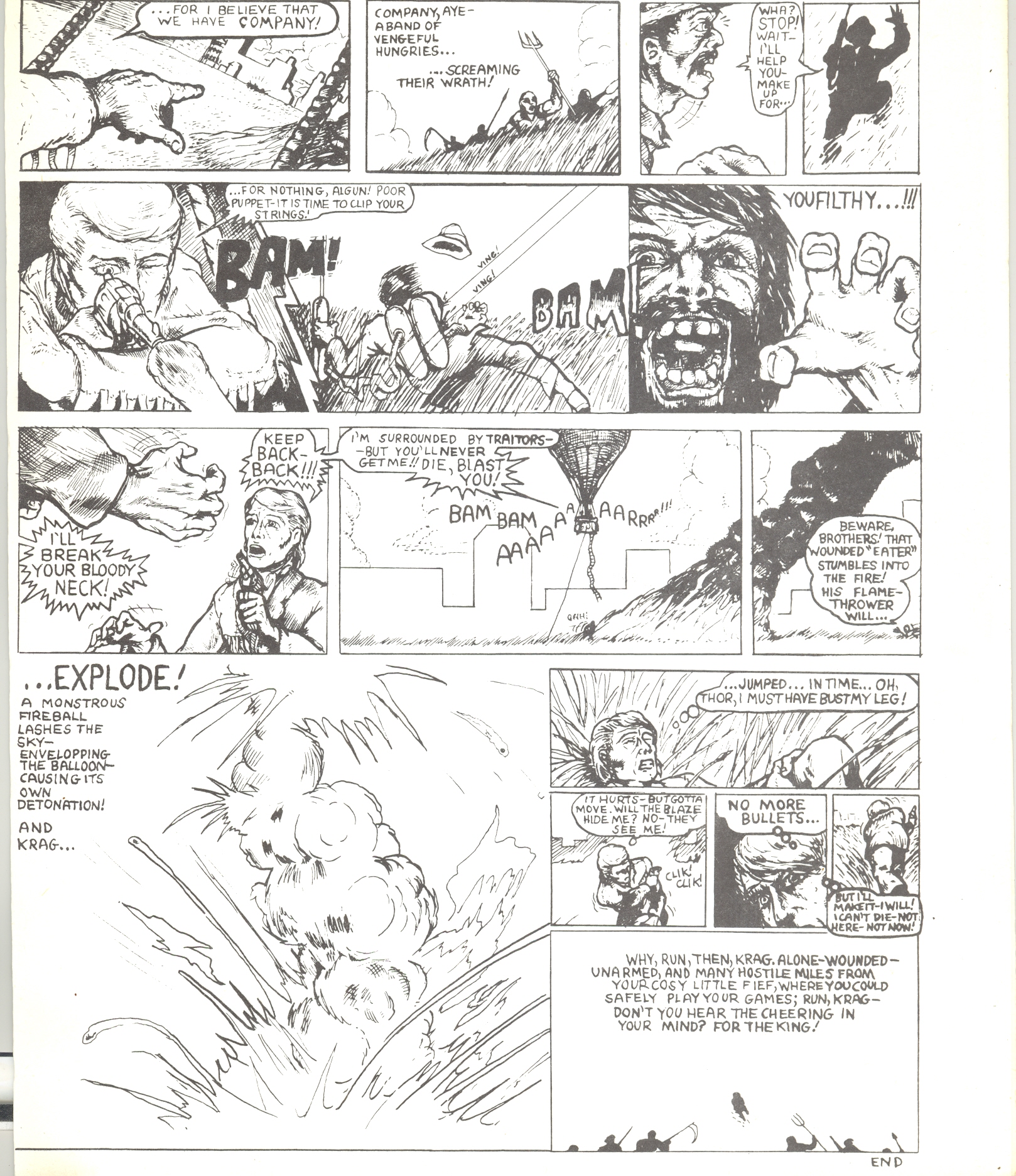

Ahmed found a 15-year-old artist named Marcelo Anciano to fill out the rest of the book:

When I finally met Marcelo the next summer, I remarked how his characters’ weapons were such blatant phallic symbols (see above). He nearly died laughing.

(Marcelo is now a film director and producer, working with Quentin Tarantino and other luminaries.)

Note in Marcelo’s back cover how he spells ‘Bizzaro’ for ‘Bizarro’. We were all over quality control, weren’t we?

The second issue was a sales disaster, as it probably deserved to be. I didn’t care; I’d purposefully disengaged myself from it, which was unfair and a betrayal to Ahmed and to Marcelo.

Today, Ahmed is known as Ahmed Shawki, the editor of the International Socialist Review. I wonder if our failed little business venture soured him on capitalism? He’s certainly grown since this first foray in the publishing business.

(One 13-year-old fan, an architect’s son, who used to come to Ahmed’s place where we’d discuss comics, was definitely not a business failure. He went on to found the Forbidden Planet chain of bookstores, the dominant direct-market distributor in Britain, and Titan Books. His name was Nick Landau.)

For years after, though, I’d take copies of issue 2 to the comics marts off Tottenham Court Road and vainly try to flog’em. This led to an embarrassing incident (and a good lesson.)

After one mart in 1975 I was hanging around while the organisers dismantled the set-up. A fellow dropped by the table where I sat and asked to see some of my purchases; we got to talking. It was Dave Gibbons, then known to me as a very prolific fan artist. He said he was working on superhero comics for an African publisher and was about to do ‘Dan Dare’ for an upcoming IPC mag called 2000 AD.

I passed him a copy of my issue 2 and awaited his opinion.

Now, Mr Gibbons is a gentleman, and I’m sure he didn’t wish to hurt my feelings. He pointed to one panel and said: “I like this one”:

As it happens, that panel is the only swipe I’ve ever done– stolen from Swamp Thing # 4.

” God sees the truth, but waits” goes the old Russian proverb.

So does Dave Gibbons! I’ve never swiped a drawing since. Never.

(“What, never?”

“No, never!”

“What, neverrrrrrrrrrrrrrrr….?”

“Well…

…hardly everrrrrrrrrrrrrrr…!!!

1973 was a watershed year for comics. And not in a good way.

The Underground smashed into a brick wall: anti-obscenity Supreme Court decisions, anti-paraphernalia laws that destroyed headshops, a general change in the culture away from perceived ‘hippie dippie’ values, all nearly killed this once-vibrant sector.

The great paper shortage of 1973 and the oil embargo of that same year put crippling pressure on the mainstream comics companies.

They also were losing quickly their traditional retail outlets, and the nascent direct market wasn’t yet strong enough to take up the slack.

Britain headed into a decade-long economic slump, putting paid to ‘swinging London’ (and birthing Punk.) ‘Dark they Were and Golden-Eyed’ went out of business in 1981.

promotional button by Hunt Emerson

Still, in those old crude fanzines of Britain’s early seventies are the seeds of future accomplishment. It was here that the young Dave Gibbons, Brian Bolland, Kevin O’Neill and so many others took their first stumbling steps.

Bram, Diane, Rob, Des– I just want you to know that the whiny, loud, obnoxious fanboy 15-year-old you knew as Alex is now a whiny, loud, obnoxious fanboy 56-year-old, and he’d like to buy you all a jar so we can lament how comics have gone to the dogs since our day. ‘When I were a lad…”

As for me, I never published again, and remain a dilettante in comics. Looking back, I regret that I didn’t pursue an entirely different talent I had for caricature; it would’ve borne more interesting fruit.

Ah, nostalgia just ain’t what it used to be…mais où sont les neiges d’antan? Where are the snows of yesteryear?

Below is a recent bit of foolery, done for an online ‘exquisite corpse’ jam comic:

That’s about the limit for me nowadays.

Yet, hard as I’ve been on my adolescent self — still I’d give up everything I have to relive those days, those golden years gone forever, when I was teenage cartoonist.

****************************************************************************************************

For a good overview of the British fanzine movement, check out

Dez Skinn’s entertaining take.

An incredible resource:

the International Times archive.

Lastly, that jam I contributed to:

Good fun, check it out

Hello! You may remember me from such insightful posts as Visual Languages of Manga and Comics and, er, well, just that one, really. You shall all be subject to me on a regular basis for a while, as Noah has asked me to be a monthly columnist. At the moment, I’m not sure what direction I’m going to go with this, but I’ll play it by ear.

This month, as I’ve just come back from a vacation to the UK and am still jet-lagged, I’m going to just blather on a bit about a current favorite TV show of mine and why I think one of the main characters is the most fantastic female character I’ve seen in a long, long time.

Der Krieg (the war) by Otto Dix

When I think about German Expressionism the Isenheim Altarpiece (1506 -1515) by Matthias Grünewald comes quickly to my mind. I know that it isn’t exactly an Expressionist painting (I’m aware of the anachronism), but all expressionism (and some Surrealism too: Max Ernst, for instance) is there already.

One of the topics explored by Matthias Grünewald in his altarpiece is ergotism, as we can see in the polyptych’s wing shown below:

It represents Saint Anthony being harassed by demons, but if you look closely on the lower left corner of the painting you will see a patient afflicted with Saint Anthony’s fire. This disease was caused by the ingestion of ergot infected rye and other cereals. Ergotism produces seizures and hallucinations (hence the demons) as well as gangrene of the limbs and peeling. Ergotism also explains the strange look of Matthias Grünewald’s Christ in the aforementioned altarpiece. There was a spiritual connexion between the son of God’s suffering and the suffering of the diseased.

The depiction of human pain (often psychological pain instead of physical agony) isn’t the only theme explored by Expressionist painters (and it certainly isn’t this artistic movement’s monopoly), but it certainly is an important part of the aforementioned style. Otto Dix remembered Matthias Grünewald and the polyptich form (a tryptich with a predella: a gallery comic) when he painted Trench Warfare, 1929 – 1932, his own version of human suffering in WWI:

Nimosaku Shimada, 2010, Digital Manga/Oakla Publishing

Aaaaarrrrggggghhhhhhhhhhhhhhhh!

No, really. This is a disaster. It can’t be happening. I cannot go on. I cannot bear the pain. Etc., etc. Because I thought there was a second volume. I don’t know why I thought that – probably confused it with Portrait of a Vampire, which does have a second volume – not that I care. Damn it. I have finished How to Seduce a Vampire and I was secure in the knowledge that there was more waiting for me, BUT THERE ISN’T. There isn’t even anything else available by Nimosaku Shimada. I may take to my bed and pine. Pine desultorily, and gnash my teeth in sheer vexation. Then nap.

This book snuck right up on me. I was wary, because, you know, my heart’s done time. (I thought that was kind of clever. You see, “Heart’s Done Time” is an Aerosmith song, from Permanent Vacation, a not completely intolerable album that was the middle of the end for a band that used to be one of the best and became – what they became. Heavy sigh. Now I’m thoroughly depressed.) Anyway. I love me some vampires, and vampire stuff has never been hotter, but – to take liberties with the state motto of Alaska – the odds are good, but the goods mostly pretty much suck. Since it is too late to make a long story short, let us at least summarize succinctly by saying I am wary about vampire films, books, and manga. I expect to be disappointed, and I usually am.

For this column, I’d like to return to the subject of comics criticism. A while back, HU hosted a Popeye roundtable, which raised some interesting general questions, but seemed to stop from lack of enthusiasm before it went very far. Not being in a position to contribute at the time, I would like to resurrect it for the purpose of raising a number of issues pertaining to how we talk about comics and art.

Noah in his ambiguous essay on E. C. Segar’s strip expresses frustration at what he perceives to be its shallowness:

Though I enjoyed the energy of the drawing, and the Sea Hag and Goon provided some evocatively creepy moments early on, the limited range of the humor, and its empty-headedness, quickly becomes numbing. Wimpy is lazy, Wimpy eats a lot, Popeye is noble, defends the underdog, and always wins.

Robert, in his piece, which references a series of earlier, excellent reviews on his own site, concludes that the strip is “largely of historical interest”, writing:

The challenge I gave the work was for it to transcend that description. It occasionally did; there were flashes of satirical and absurdist genius every now and then. “The One-Way Bank” storyline from Volume II and the finale of “The Eighth Sea” storyline from Volume III stood out, and I was especially taken with Volume II’s “The Nazilia-Tonsylania War” — its treatment of state and military folly ranks with Dr. Strangelove (almost) and Duck Soup. (No pun was intended with the name “Nazilia,” by the way.) However, Segar was generally far more enamored with farce and slapstick for their own sake than he was with satire. That greatly limits the appeal of his work, at least for this adult reader. Farce and slapstick that don’t connect with anything deeper are best in small doses; they tend to wear out their welcome fairly quickly.

So the strip is less than great because it is simplistically conceived and primarily concerns itself with slapstick and farce, only rarely ‘transcending’ these. For Robert, this happens when it becomes satirical, because that somehow connects ‘deeper’ than mere laffs.

This seems to me a holdover from modernist conceptions of aesthetic value that privilege the framework provided by the ‘high’ arts. Robert even spells out this bias:

No reasonable person would consider it on the level of Faulkner, Kandinsky, or Jean Renoir’s work, but it looks right at home when viewed alongside the efforts of Mae West, W.C. Fields, and the Marx Brothers. I have nothing against the popular-entertainment standard for determining “good” comics, by the way. If a comic entertains people, it’s doing its job. And if it’s entertaining people to the extent that it becomes a pop-culture phenomenon, which Segar’s Popeye certainly did, then it’s doing its job terrifically well.

…But it still isn’t as great as Faulkner, Kandinsky or Renoir. Invoking the consummate elitist Harold Bloom’s definition of the canon as what should be taught in our schools, Robert judges Popeye out. But why? He has himself conceded that it gripped more than one generation of readers and became a pop-culture phenomenon. Isn’t that worth teaching in schools? And what about those great humorists cited? Irrelevant to the understanding of our culture?

My intention here is not to claim that Popeye – or Thimble Theater if we want to be correct – is the equal of the best high art had to offer at its time (conversely I’m not saying that it ain’t either). What I am saying is that it will necessarily look impoverished when judged in the framework of high culture, and that I find such a yardstick unhelpful in assessing its qualities — qualities that clearly resonated widely and persistently. Although we have now for several decades described our times as postmodern, with everything that entails, the elitist legacy of modernity is amazingly hard to shake.

Noah recognizes this, essentially framing his dismissal of the strip as personal preference. He compares with another low-culture medium, which has received even less high-culture acclaim: television, concluding that,

…what is and isn’t considered art is really arbitrary. Comics critics have spent a lot of energy for the past decades trying to get comics accepted as high art. They’ve had definite (if not unqualified) success, and now even frankly pulp, unpretentious works like Popeye can be put up in galleries, given lavish reissues, and hailed as canonical examples of the form.

I would guess that someone like Noah, who spends a fair amount of energy as a critic acclaiming the qualities of some of the most commercial iterations of contemporary pop music, would be unsatisfied with the kind of high-culture point of view brought to bear on comics by some of its more assiduous critics at this current, mercurial juncture in their history.

Having long regarded hip hop as one of the most inspiring cultural manifestations of the last 30 years, I sympathize. It has been interesting to watch its fortuna critica in the cultural establishment as it has evolved: regarded initially as a fad, its staying power has come to be recognized and it is now classified as a legitimate musical genre, but it still isn’t considered an art form on the level of, say, rock music. “Gangsta Gangsta” by N.W.A simply doesn’t cut it when measured by the yardstick of “Like a Rolling Stone”, but it is undeniably a hugely resonant piece of work, every bit as influential on the generation from which it sprang.

Similarly, at the time of Thimble Theater, surely ‘no reasonable person’ would consider something like ragtime or jazz on the level of opera. Yet, today, these forms and their progeny are regarded as entirely respectable art forms, capable of greatness akin to that achieved in classical music. Music unites us in ways that other art forms don’t, and we seem to be more receptive to “shallow” qualities there than we do in literature, fine art, or even comics. Perhaps this is not so surprising, since music generally is less cerebral than those forms, making us appreciate — and intellectualize — our emotional and visceral responses to a higher degree.

And actually at least one perfectly reasonable person did consider ragtime and jazz, and with them a whole range of other popular forms such as vaudeville, the movies, and yes, comics, on the level of high culture. A cultural critic and New York correspondent of T. S. Eliot’s Criterion, his name was Gilbert Seldes (1873-1970). In his precocious defense of popular culture, The Seven Lively Arts (1924), he wrote:

If you can bring into focus, simultaneously, a good revue and a production of grand opera at the Metropolitan Opera House, the superiority of the lesser art is striking. Like the revue, grand opera is composed of elements drawn from many sources; like the revue, success depends on the fusion of these elements into a new unit, through the highest skill in production. And this sort of perfection the Metropolitan not only never achieves — it is actually absolved in advance from the necessity of attempting it. I am aware that it has the highest-paid singers, the best orchestra, some of the best conductors, dancers and stage hands, and the worst scenery in the world, in addition to an exceptionally astute impresario; but the production of these elements is so haphazard and clumsy that if any revue-producer hit as low a level in his work, he would be stoned off Broadway. Yet the Metropolitan is considered a great institution and complacently permitted to run at a loss, because its material is ART. (pp. 132-133)

Lest he be dismissed offhand as the kind of contrarian philistine such statements might evoke in us today, I hasten to supply the following; during a visit to Picasso’s studio in Paris, he was shown a fresh canvas by the master, which prompted in him a synthesis:

I shall make no effort to describe that painting. It isn’t even important to know that I am right in my judgement. The significant and overwhelming thing to me was that I held the work a masterpiece and knew it to be contemporary. It is a pleasure to come upon an accredited masterpiece which preserve its authority, to mount the stairs and see the Winged Victory and know that it is good. But to have the same conviction about something finished a month ago, contemporaneous in every aspect, yet associated with the great tradition of painting, with the indescribable thing we think of as the high seriousness of art and with a relevance not only to our life, but to life itself — that is a different thing entirely. For of course the first effect — after one had gone away and begun to be aware of effects — was to make one wonder whether it is worth thinking or writing or feeling about anything else. Whether, since the great arts are so capable of being practised today, it isn’t sheer perversity to be satisfied with less. Whether praise of the minor arts isn’t, at bottom, treachery to the great. I had always believed that there exists no such hostility between the two divisions of the arts which are honest — that the real opposition is between them, allied, and the polished fake. (pp. 345-346)

I think we could do worse than take a cue from Seldes’ notion of the ‘lively arts’ in our current reassessment of comics as cultural phenomena and art. About the comic strip:

Of all the lively arts the Comic Strip is the most despised, and with the exception of the movies it is the most popular. Some twenty million people follow with interest, curiosity, and amusement the daily fortunes of five or ten heroes of the comic strip, and that they do this is considered by all those who have any pretentions to taste and culture as a symptom of crass vulgarity, of dullness, and, for all I know, of defeated and inhibited lives. I need hardly add that those who feel so about the comic strip only infrequently regard the object of their distaste.

Certainly there is a great deal of monotonous stupidity in the comic strip, a cheap jocosity, a life-of-the-party humour which is extraordinarily dreary. There is also a quantity of bad drawing and the intellectual level, if that matters, is sometimes not high. Yet we are not actually a dull people; we take our fun where we find it, and we have an exceptional capacity for liking the things which show us off in ridiculous postures — a counterpart to our inveterate passion for seeing ourselves in stained-glass attitudes. (p. 213)

Seldes doesn’t mention Thimble Theater, and couldn’t have known Popeye (on account of he hadn’t been born’d yet), but he regarded highly its neighbor in the New York World, Krazy Kat, whose creator George Herriman he considered one of the two genuine artistic geniuses in America at the time (the other was Charles Chaplin). In his famous essay on that strip, he wrote:

With those who hold that a comic strip cannot be a work of art I shall not traffic. The qualities of Krazy Kat are irony and fantasy — exactly the same, it would appear, as distinguish The Revolt of the Angels; it is wholly beside the point to indicate a preference for the work of Anatole France, which is in the great line, in the major arts. It happens that in America iron and fantasy are practised in the major arts by only one or two men, producing high-class trash; and Mr Herriman, working in a despised medium, without an atom of pretentiousness, is day after day producing something essentially fine. (p. 231)

Granted, Krazy Kat has received greater high-culture recognition than any other strip of its day, and seems more effortlessly to accommodate a fine arts perspective, but I don’t see why one couldn’t formulate something along similar lines for Thimble Theater. Noah suggests that one might compare the strip with the cinema of Buster Keaton, which strikes me as particularly instructive:

Keaton’s work rightly occupies an important place in the cinematic canon, despite it being similarly resistant to the kind of interpretative framework that eschews slapstick. As the New Wave filmmakers recognized, however, his auteurial presence is acutely felt throughout his work, and it gives us a highly original, fatalistic and uncannily comic conception of depersonalized action in a world of strange, fickle serendipity.

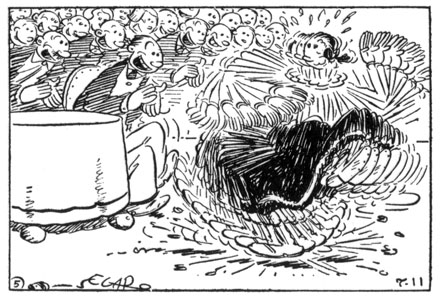

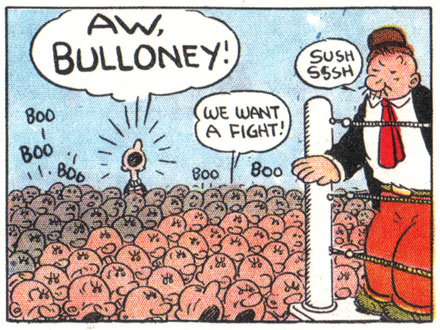

Now, let’s look at fairly typical, self-contained Sunday page from Thimble Theater (sep. 30th, 1934):

On the surface, it delivers a straightforward gag pitting, as is so often the case, Popeye’s morality against Wimpy’s lack of same. But Segar is anything but a utilitarian gang man; he proceeds like a cartoon behaviorist, generously packing in as much character detail and humorous instance to create a highly seasoned repast, all the while unfolding a strongly intuited moral ethos.

Watch his unaffectedly plump line and vernacular wit unfold across the page: Wimpy insinuating himself into the frame and the duck hunt, bodily/verbally; his mention of his favorite animal, “hamburger on the hoof”; the manner in which he splays his three surplus fingers while pressing his nose to quack (and, inevitably, to hamburger moo); his poker face registering the hit, turning to sniff; the derision on his face against Popeye’s soon-to-vanish irascible scowl; the silent burial bookending Popeye’s contrition, Wimpy empathetically yet efficiently settling the mound; the exchange: “WHAT! NO DUCK?!” — “Yeah, no duck”; the unchanged expression on Wimpy’s face as he kneels caninely to exhume the duck with speed, his coattails waving; it remains unchanged as he sits at the end, counter to the left-right flow, roasting the kill.

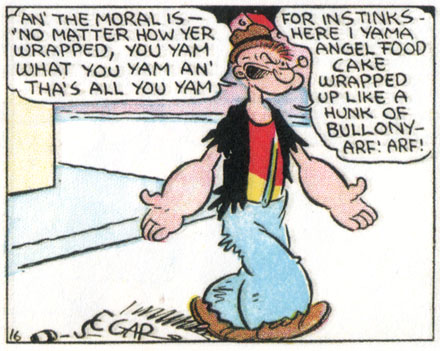

Clear in presentation, yet richly studied, this sequence is a perfect summation of the profane reality of Thimble Theater. A true comedic hero, Popeye is pugnaciously selfless in a world governed by selfishness. He always restores order around him (often, disturbingly, by violence), but is simultaneously given enough of a tragic edge — his morality is rarely reciprocated — to keep us involved. As with Keaton, there’s a fatalistic undertone to his and, by its frequent extension to the rest of the cast, the strip’s indomitable catchphrase: “I yam what I yam, an’ that’s all I yam!” It’s trenchantly inspirational and it is great fun, so why can’t it be great art?

Part of the answer, if one compares with cinema, is that it has taken comics much longer to expand its field beyond a fairly restricted set of idioms and genres, all of which are candidly low culture. It hasn’t had its James Agee, though people like Donald Phelps, R. Fiore and Art Spiegelman have done their best in recent decades; they haven’t had their Raymond Rohauer and have only recently begun experiencing comprehensive restoration and republication, and they haven’t had their new wave until now.

Which brings us to the matter at hand: this is a time of redefinition for comics, which is not only manifest in contemporary cartooning, but naturally extends back to encompass its history. Neglected by critics and historians, and forgotten even by most cartoonists, the classics now demand our attention for what they teach us about their time and the evolution of the form, but ultimately also as works of art. Though it is surely healthy to assess comics in the expanded field of cultural production being opened up as distinctions between high and low are collapsing, to not cut them any exceptionalist slack, it would seem ill advised to judge them according to antiquated systems of hierarchical exclusion.

PS — Because Noah mentioned them as part of his high-low concordances, I can’t help bringing in the Coen brothers here. While it is correct that they are becoming canonized as directors, it is remarkable that their best loved, and arguably best though not most critically acclaimed film, The Big Lebowski, is so unabashedly shallow. It totally fails the modernist test as a work of art, and yet there it is, and it’s glorious.

Squint, imagine some more punching, and it might almost play at the Thimble.