Dominique Goblet’s and Nikita Fossoul’s Chronographie (Chronograph)

Some of you monolinguists may ask yourselves why do I bother to write at the HU about foreign books written in a foreign language (?)… There are a variety of reasons which explain why a columnist chooses his or her topics. Being a foreigner myself (and someone who manages to, at least, understand Latin languages) I have access to many books that aren’t available in North America. In this day and age though you’re just a few clicks way from these great comics (I’m old school, so, don’t expect me to say “graphic novels” very often).

My last post was about a scriptwriter who wrote in Spanish. His comics are a bit verbose (this isn’t a negative criticism: as I said elsewhere: I prefer great words to mediocre images and vice-versa, of course), not to mention completely out of print, but my other stumblings were wordless or almost wordless. (Unfortunately that’s not what happens with the links below: they mostly lead to not so silent French and Belgian sites.)

When I say “almost” I’m not implying that the words don’t count (contrariwise to a somewhat goofy comment that I wrote answering to another comment by Noah who “accused” me of just writing about European art comics). For instance, I didn’t mention in my first post that Pierre Duba wrote a few phrases in Racines about identity and quoted Norwegian writer Tarjei Vesaas. (I thank my friend Pedro Moura who linked Racines to another central book in the ideal comics canon: The Cage by Martin Vaughn-James; maybe I’ll come back to Duba one of these days; I have to, I’m afraid!…)

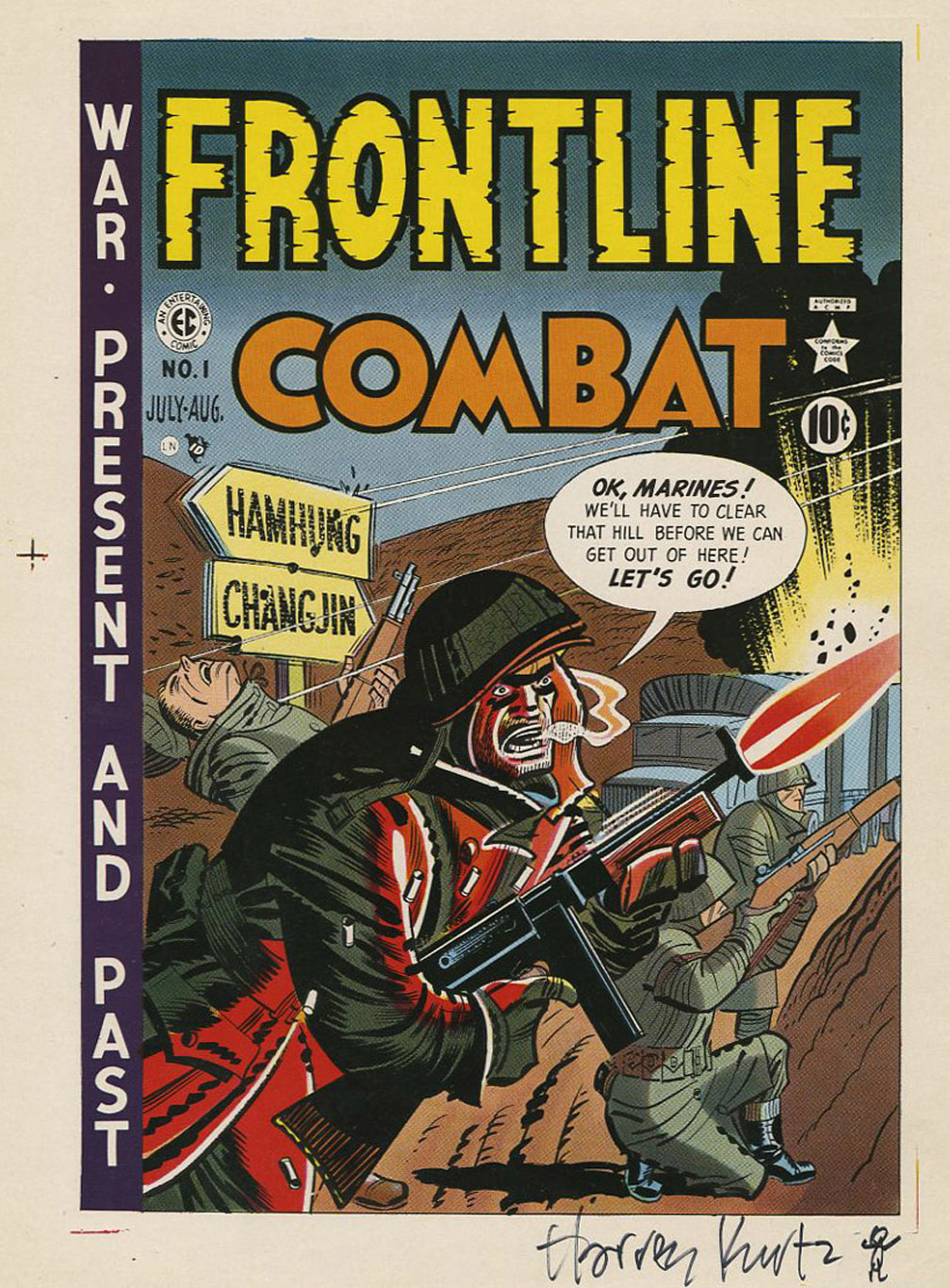

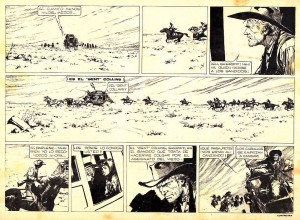

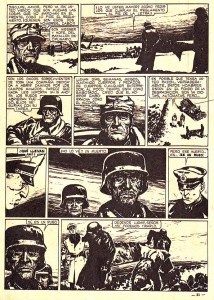

I wrote about Héctor Germán Oesterheld because I think that he is the best comics writer that ever existed (yes, better than Alan Moore) and the world needs to know more about him. Being an Argentinian he’s at a disadvantage (like everyone else that worked or works in comics outside of the holy trinity: Japan, U.S.A., France-Belgium). This applies even to countries with fairly important traditions in the field like Spain and Italy…

My other posts just mean that a comics avant-garde scene (Bart Beaty calls it a postmodern modernism – 2007) truly exists in Europe (this is an idea that goes back to Jan Baetens in his analysis of Autarcic Comix – 1995 – as reported by Paul Gravett in the link above). What interests me the most in comics are those borderline examples that push the limits of the form. Publishers like L’Association, Six pieds sous terre, Ego comme x, Frémok frequently publish, with the help of grants from the French and Belgian governments, highly experimental books that shatter to pieces our expectations of what a comic is supposed to be. Authors like Vincent Fortemps or Jochen Gerner are part of this unpopular (to quote Bart Beaty again) cultural movement.

I will stumble on some North American comic one of these days, I’m sure, but I don’t know exactly when… (North American comics authors respect comics’ mass art tradition too much for my taste. They are afraid of being called pretentious or elitists if they forget goofy caricatures, I suppose; maybe they should embrace Milton Caniff’s, Hal Foster’ s, Alex Raymond’s tradition instead to tell contemporary adult stories? Are the technical skills a problem though? Sadly, I suppose so… those giantly talented graphic artists are hard to match.)

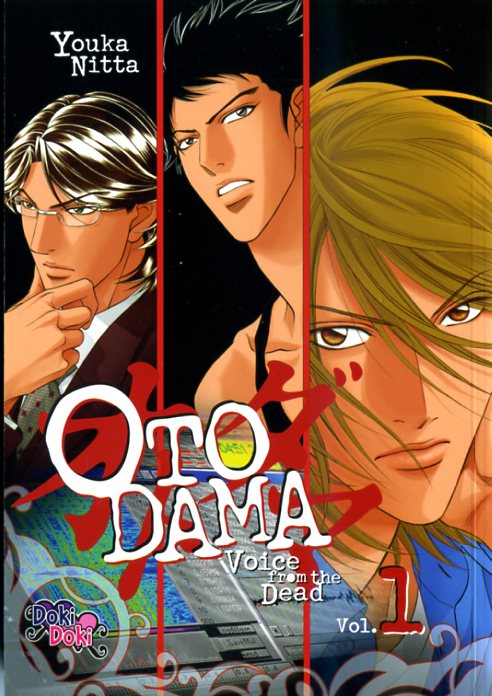

Dominique Goblet is also part of that nineties’ European comics revolution that I mentioned above (she’s a Belgian). Nikita Fossoul is her daughter.

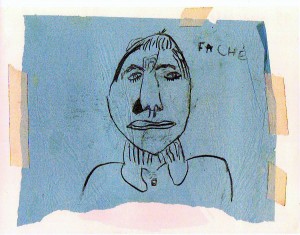

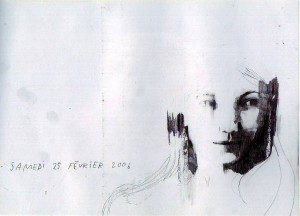

In Chronographie (another quasi-wordless book) they publish ten years of their more or less biweekly portraits of each other (Fossoul was seven years old when they began and Goblet was thirty one). Words are few and far between, but when they appear they add important meanings, not as an anchor in a Barthesian sense, but as time and context info and as emotional descriptors. It’s mostly Nikita who uses the latter saying thinks like: “Faché[e]” – “Pissed off.” Being in a powerless situation children need to pay attention to the adults’ moods. This doesn’t necessarily mean that Dominique was pissed off at the time though: it may simply mean that she appears to be pissed off and Nikita noticed this after doing the drawing (see below). (Curiously enough the words gradually disappear from Nikita’s portraits. I’m sure that there’s a paper here somewhere.)

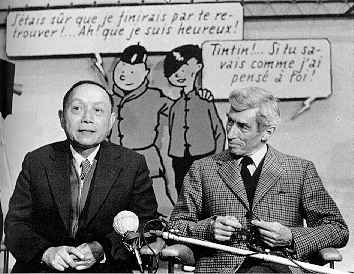

Confronted with these kinds of books this television show host asked: “Can we still talk about comics?” I would answer definitely yes, but I hardly count… My answer is in accordance with my expansion of the comics field to include things from the distant or recent past (said expansion may be seen as an anachronism and a decontextualization). What’s new in this case is that these authors really are comics artists. L’Association (Chronography‘s publisher) is a comics publishing house (whose publisher Jean-Christophe Menu, as been one of the most vocal actors in the comics field to defend that really there is a comics avant-garde). If Frans Masereel never thought about it, I’m sure (I include him in comics history without his permission), they, on the other hand, want to do comics in a contemporary high culture context. As Dominique Goblet put it, answering the question:

We are at the crossroads between the visual arts and comics. The link that unites all this is a passion to tell stories.

(I would replace “tell stories” for “do sequences” because many things in, for instance, the Fort Thunder style shatters the narrative. On the other hand I suppose that it is defensible to say that two images put together, no matter what they represent, do tell a story of sorts… Also: the visual arts always have been a part of comics, so, I don’t see where the crossroad is. What Dominique Goblet says is understandable though: the visual arts have an important history of experimentation and comics don’t.)

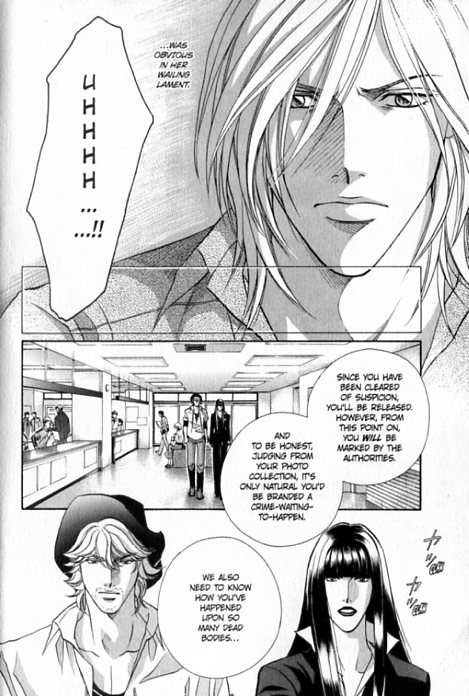

In almost every session Goblet and Fossoul chose the same technique, the same composition solutions, explored the same particular aspects; they even shared model poses sometimes (see below). This coherence can only mean that Dominique Goblet was the art teacher and Nikita Fossoul was the student.

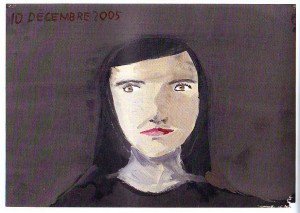

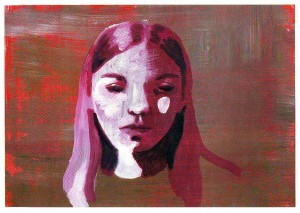

The book begins with graphite and black colored pencil line drawings. It continues exploring washes, pastels, collages, acrylic paint. The supports are all kinds of paper (old papers, drawing papers, etc… two of the drawings seem to have been done on some sort of synthetic board).

The problem of resemblance is at the center of the portrait genre. If Dominique Goblet solves this problem easily Nikita Fossoul doesn’t even address it. As she put it in the book’s postface (in both French and English, by the way):

So I drew what I sensed (almost) more than what I saw: a mood, a special complicity… Thanks to this lack of interest in strict likeness, I too could let go and no longer be afraid of ‘going wrong[,]’ and that is how I dared to carry on.

As she also says drawing was a game at first, but an evolution can easily be traced in her drawing skills. As for Dominique Goblet she draws in a contemporary sketchy (sometimes fragmented) style, but she never destroys her model’s face. She obscures it sometimes because she has a real interest in shadows and light (great vehicles to convey mood). Sometimes she just did beautiful simple drawings like the two below.

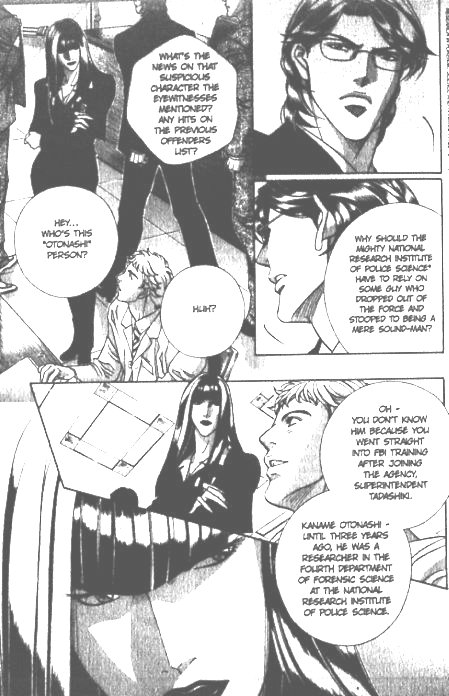

Ten years is a long time in a person’s life and Chronographie is about the passing of time, but what story do these faces tell us? When she began this project Dominique Goblet wanted to explore a mother / daughter relationship:

I have always wondered about what is called ‘maternal instinct[.]’ To be honest, I have never fundamentally understood what it could mean.

In any case, to my great regret I have never been sure of anything that obvious. I don’t know if I resemble those mothers who talk about unconditional love, instinct, the need to unreservedly protect.

One more time we reach the conclusion that philosophy, science, the arts start with the same impulse: the will to explore, the will to know beyond all clichés and common sense. A book depicting saccharine moments between a mother and a daughter would be a kitschy thing indeed. But that’s not what Chronographie is: there are moments of laughter, there are moments of bliss and there are moments of sadness. Life is a lot more complex and interesting than any pop myth (Dominique Goblet again):

Many things were said without words. The sequential work is carrying on, in a way, very slowly. What is told here traverses the prism of an imperceptible movement. The years spent together…

The essential is told, we have given more of ourselves than any memory would have done. This is no longer about details, let alone anecdotes.

The myth of the mother-daughter bond appears in another form: a silent tale.

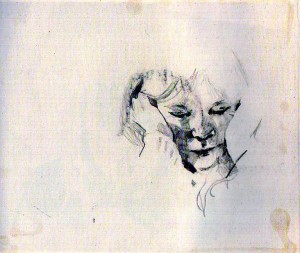

Imagining myself as a devil’s advocate I could say that Nikita Fossoul’s drawings are amateurish and Dominique Goblet’s drawings are sometimes great, sometimes not so great. All that is true, but is it really important? What matters is the inquisitiveness, the patience, the bond between mother, daughter, and the readers… life being lived and shared (that’s what real art is all about)… those rare moments in which we receive our rewards and get some answers… That’s why I finish this post with the only portrait in the book in which a young artist (she was twelve years old) captured her mother’s likeness, without even trying… It’s no wonder that she saw her with a pair of worried, slightly sad, eyes the size of the world… her world…