You’re probably familiar with it, even if you’ve never heard the word for it. “Fandom” refers to the subculture of people who are fans of any topic. Being a fan is more than simply liking something, and usually more than a hobby. Fans devote considerable time and energy to their fandoms, sometimes even creating works based on it. While people can be fans of anything from baseball to crochet, some of the most involved fandoms are the fandoms surrounding fictional works, particularly science fiction and fantasy. No doubt you’ve encountered at least one of these fandoms: Harry Potter, Lord of the Rings, the Bible.

In some sense, these fandoms have always been with us. Before the internet, fandoms were widely dispersed networks of people who communicated by means of mail and conventions—meetings for fans to gather and discuss their favorite fictional works. The first science fiction convention was held in the 1930s, and modern science fiction and fantasy fandom evolved from that. Another milestone was the 1970s, sometimes called the “New Wave”, when large amounts of people became interested in science fiction and fantasy. One of the most popular fandoms—and the fandom that influenced so much of what came after—is another thing that you’re probably familiar with: the Bible.

Between 1967 and 1969, three books were published, called the Torah (Teaching, or the Five Books of Moses), the Nevi’im (Prophets), and Ketuvim (Writings). These three books together formed one book—a fantasy novel about the history of the world and a group of people in it. The book is traditionally called the Tanakh.1

While a small group of people became highly invested in the Tanakh, publishers did not feel that they were selling enough copies. It went out of print after three years. Usually, that’s the end of the story: a book is published, a show is made; people like it for a while, and then it’s forgotten. But fans of the Tanakh were extremely loyal. They lobbied for republication of the book, and when that failed, they took matters into their own hands. For decades, they held conventions and produced fanzines—collections of fan works published in bound form, and sent to fans with subscriptions. Fan works included art and fan fiction, stories based on the characters and situations in the original novel.

While the public seemed generally aware that Tanakh fans existed, the fandom was largely ignored. Sometimes there was an outside interest in the conventions and fanzines; outsiders periodically commentated on the inexplicable nature of Tanakh fandom. Sometimes there was even ostracism, or outright condemnation: Tanakh fans were criticized for taking the book so seriously—particularly since Tanakh was very different from mainstream literature.

As a result, Tanakh fandom remained small, but loyal. Though marginalized, it became highly organized; fans created their own traditions and jargon, building on the original text even as they celebrated it. Tanakh fandom laid the foundation for much of fandom as we know it, but the biggest way it has influenced not only fandom, but modern culture, is the spin-offs.

In 1987, there were enough Tanakh fans and enough lingering interest to justify the creation of a new series set in the universe of the original series, called the Testaments. The Testaments are two books, generally called the Old and New. The Old Testament is basically a “reboot” of the original series (à la Moore’s Battlestar Galactica in 2004, or Moffat’s recent Sherlock), while the New Testament is a sequel. The sequel incorporates references to favorite characters, including God and Satan, while introducing a next generation. At the center of the next generation is a character called Jesus Christ.

The Testaments were a huge best-seller. Many fans of the Tanakh became fans of the Testaments as well, and many new fans were introduced to the universe through the updated works. Even people who aren’t “fans” in the obsessive sense of the word enjoy the Testaments. Furthermore, even people who have never read The Testaments or even actively dislike them, generally have a little knowledge of the universe. Basically, they were the Harry Potter of the late 1980s; the Testaments have been adapted into several feature length films, and have become integral to modern pop culture.

Fans of the Testaments are more often fans of the New Testament than they are of the Old Testament, though the re-imagining of the original text is highly respected. Christ, however, was the main draw for many fans, and Christ-based fandom remains one of the strongest and most active fandoms today. While a large population has read and enjoy the New Testament, and a large percentage of that would call themselves fans, there is a small, extremely active contingent of Christ fans who almost make rabid look tame.

In the last decade, these fans have received more attention than ever before. For a long time, fandom was peripheral enough that not only was it easily ignored, but it was difficult to observe. With the advent of modern media, particularly the internet, it has become possible to view fandom without being a part of fandom. The past fifteen years have seen a plethora of documentaries, articles, and scholarly work on these fandoms, while the fandoms themselves have grown, becoming highly organized and active.

Due to this, much of the practices that otherwise would not have been exposed to the public are now common knowledge. Documentaries such as Christies2, released in 1997, detail the behavior of active Christ fans. Some fans saw Christies as exploitive, but most agree that Christies treated the subject fairly. From the outside, many of the actions of Christ fans may seem strange or aberrant, but to those in the fandom, such actions are natural expressions of their love of a text.

One of the most common forms of said expression is the fannish gathering. Gatherings don’t always have to be conventions; it can be as simple as a couple of fans getting together to watch a television show or discuss a book. Although there is not an episode airing weekly to watch, weekly gatherings are a staple of Bible fandom, as they were in Buffy the Vampire Slayer when the show was airing. Instead of watching television, however, Bible fans come together to discuss the book, read passages, and even sing songs and play games–as fans do at Harry Potter parties.

Different fans participate in fandom in different ways, but for many, it’s the feeling of community that is as important as the text that draws them together. There would probably be Bible fans in a vacuum, but it’s definitely the case that sharing ideas and associating with like-minded people not only brings the fans who participate pleasure, but sustains the fandom itself. Some fans do not consider those who do not participate in gatherings active members of the fandom.

One of the largest types of fannish gatherings is the convention. Conventions are held year round by various branches of fandom, but the biggest ones recur annually at roughly the same date each year. While conventions are traditionally hosted at one venue, Bible fan conventions have become so large that they are held all over the world in many different places. Large numbers of fans turn out for these events. Some are highly devoted, and some are just people who enjoy the text and want to be a part of something. For some people, it is much like a holiday.

One thing you may see at a convention or fannish gathering is something called filk. Filk is music based on a fandom. Much like fan fiction, filk uses characters and themes from the stories, and weaves it into something new. While new filk songs are being written and performed all the time, some are so traditional that any Christ fan you ask knows the words.

Another thing you might see at a fannish gathering is cosplay, which often goes hand in hand with LARP. Cosplay is a portmanteau of “costume play,” and refers to people who dress up according to a particular fandom. While traditionally, people dressed up as characters they like, more often in Bible fandom people will dress in garb merely inspired by the universe. You may have even seen someone in cosplay; one traditional costume is a black suit with a white collar. Some people take cosplay to the extreme and remain in costume at almost all times.

LARP stands for live-action roleplay. In roleplay, like cosplay, people can “be” certain characters they like, not just by dressing like them, but by acting how they think they would act. While people can discuss how they think characters might act, they can also act it out, using props and sets made to look like things and places from the fandom text–thus the term, “live action”.

LARPing was not always a part of Bible fandom. In the early days, dressing up and acting out parts was restricted to something called morality plays. Morality plays could be performed at fannish gatherings and conventions. Most fans are no longer interested in that type of performance, although the performance of the birth of everyone’s favorite character, Jesus Christ, is a tradition at some conventions.

For some fans, however, LARPing is essential to the fandom. A central scene in the New Testament is when Jesus Christ eats his last supper, and tells his friends that the bread and wine is actually his flesh and blood. Some Christ fans act this out almost religiously; they have stand-ins for Christ offer them wine (or juice) and crackers to represent the bread and wine, and eat it at least once a week. While many people outside of fandom—and many fans within the fandom as well—consider this behavior extreme, the fans who practice this tradition see it as an essential part of being a fan.

A central aspect to some fandoms is what was called “the Game” in Sherlock Holmes fandom. Some fans believe Sherlock Holmes was a real person. More often, fans are aware that Sherlock Holmes was an invention of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, but they are still interested in thinking of Holmes as having existed. To this effect, they try to gather as many “facts” as they can about Holmes’ actual life. Using Doyle’s texts, they pull details about when Holmes solved which cases, when he was born, and when he died.

While many Christ fans know the events of the Testaments to be fictional, they still think of Jesus as a real man. Although most Christ fans are not as concerned as say, Holmes fans about getting dates, etc correct, a central part of LARP—and the Christ fandom as a whole—is the “reality” of Christ.

Another thing you will see in fandom is the “Big Name Fan,” or BNFs. BNFs are fans who are well known in the fandom for one reason or another, whether it is for holding gatherings, writing copious quantities of fanfic, or perhaps even having some influence on the industry that owns the copyright on the text. While not every fan is familiar with a particular BNF, enough people have heard of them that they are considered by some to hold a lofty position in fandom. Some are even considered to hold a certain amount of power, as though they have some influence over fannish interpretation of the text.

The BNF in some circles of Christ fandom is a man known by the handle “Holy Father”, AKA the Pope. Other circles of Christ fandom decry the Pope. Others don’t understand why he’s famous, and never read his meta3 on the Testaments. But there are some who regard the Pope as an authority in the fandom, feeling that only his interpretations are correct.

This and other disagreements between fans can lead to something called fandom wank. While “wank” was initially a term used in fandom to refer to works and comments that were self-congratulatory and aggrandizing, these days the term can also to refer to various kerfuffles that happen in fandom. It may seem strange, or even silly, that disagreements about a book can lead to such heated debate and sometimes even downright nasty verbal abuse, but many fans take fandom seriously. Wank can occur over anything from disagreements about the details of Christ’s “real” life, to differences of interpretation, to lack of respect for BNFs, fanfiction, and—as is most common in Bible fandom—disputes over canon.

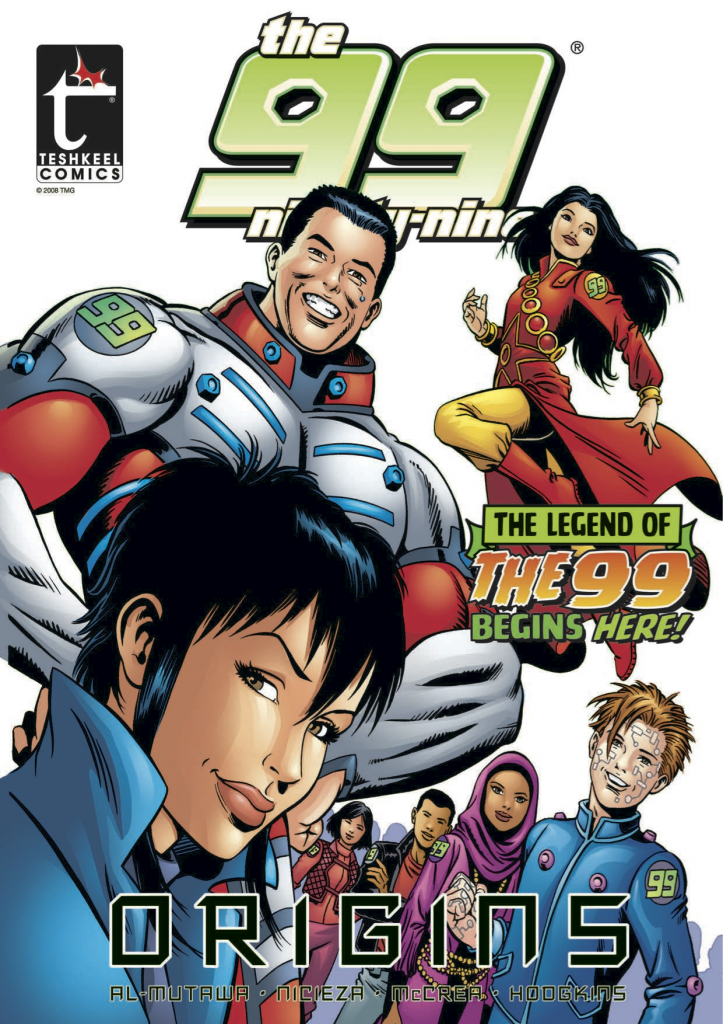

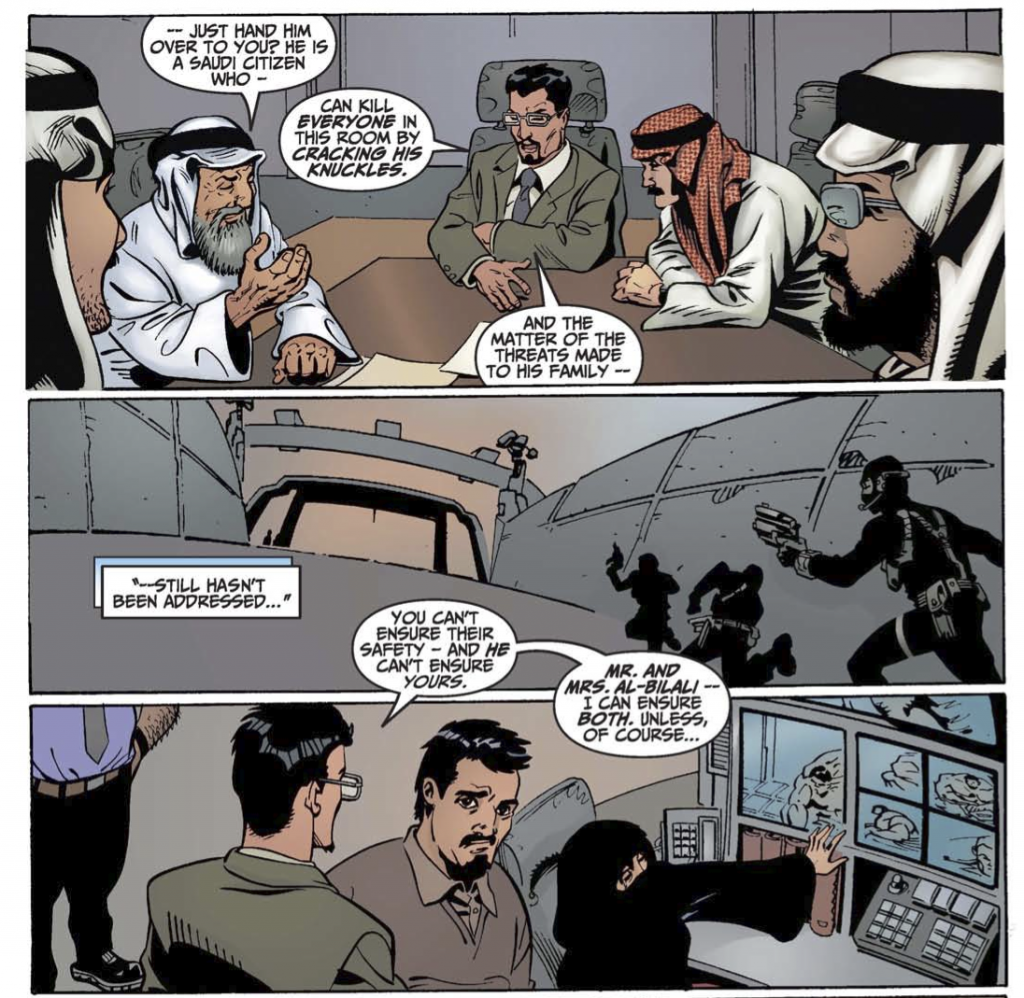

The success of the Testaments inspired a slew of other spin-offs, including new re-imaginings, such as the Qur’an in 1993 and the Book of Mormon in 2009. There have also been an abundance of unauthorized sequels, and many, many fanfics, some published, some only famous online. One of the most divisive issues in Bible fandom is which of these text is “official”, and which is merely an interpretation—in other words, which texts are canon.

The term “canon” is derived from religion; it has been used for centuries to refer to the Star Trek works which are considered scripture. (For instance, The Original Series and Next Generation are canon; Spock, Messiah! is not.) The first use in a fannish context was in reference to Sherlock Holmes; works by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle were considered canon, while pastiches by other authors were not.

In fandom, “canon” refers to the material accepted as “official” by the fandom. This leads to wank because fans disagree as to who may dictate what is canon. Certainly publishing companies may claim such and such a work to be canon, but some fans prefer to decide their own canon. Disagreement over canon has even resulted in factions who refuse to communicate, or allow each other at each others’ conventions.

Perhaps obviously, fans take their fandoms seriously–sometimes too seriously. In some ways, fans take their love of fiction to an extreme level, giving it much of the same importance they might give to real world issues. If fiction were so formative as some fans make it out to be, surely we would not be fighting wars in the Middle East between Kirk lovers and Picard worshippers. People would be able to marry whomever they wished, and mothers would always be free to make choices about their lives and health, if fairytales and fantasy were really an essential component to people’s lives.

In the scheme of things, it’s difficult to feel that a little fictional story about gods and monsters is important. And yet, a fan would say that those things which are blatantly untrue–the fable, the farce, the fantasy–have the power to give us perspective. Whether that perspective would bring reality sharply into focus, or whether it would instead continue to obscure the truth in the chaos that is reality depends on the nature of the canon and the fandom. A fan would say that fiction, fantasy, falsehood–the blatant fabrication of the fairytale–has a profound influence on some people’s lives and their perception of the world. It is often said that fiction can be an escape, but a fan would say that fiction is also a framework by which some form themselves and their thought, at times more comprehensible than our insane reality.

Bible fans make this claim, many believing whole-heartedly that the themes and morals of the book are relevant. Some even claim that the Bible could teach us a thing or two about what our society could become, explaining that the Bible has underlying messages about peace and love of fellow men. That the Bible may influence how people live may seem ridiculous to us, and yet many Bible fans, despite the unusual extent of their obsession, are often well-intentioned, thoughtful people. By taking to heart what’s in the text, they try to live better lives.

The sense of community offered by fandom has also changed lives. Extremely different people from all walks of life come together due to a common interest, and some fans have even united in order to work at charity events, or raise money for areas torn apart by natural disaster. Many people are less lonely due to their participation in fandom; fandom gives them a family, and makes them feel loved.

While fandom may seem strange, even irrational, it is only human. In some ways, a fan’s need for fiction is more comprehensible than another man’s attempt to explain the ugliness of our world using only fact. Perhaps, in light of this, it is story-telling that is man’s greatest endeavor, and his most powerful weapon.

*

1(Tanakh is an acronym of the three books. Acronyms are a common shorthand of most fandoms; Lord of the Rings fans call Lord of the Rings LOTR; Harry Potter fans HP, etc. While the comparison between the Tanakh and Lord of the Rings is obvious, the sequence of LOTR’s three books forms a linear narrative. The Torah, Nevi’im, and Ketuvim are far less sequential. However, just like LOTR, the Tanakh is considered one book as a whole, though the Torah is by far the favorite among fans.)

2(N.B. Some Christ fans do not enjoy the word “Christies”, feeling that it is derogatory and dismissive of the text, or that it lumps them in with fans whose behavior is extreme. They prefer the term “Christers” or “Christians.” In this essay, the term “Christ fans” has been used exclusively in order to avoid offense.)

3“Meta,” the pretext which means “on” or “about”, is used in fandom to refer to thoughts and interpretations of the text. Meta can be discussed or recorded, and often appears in the form of essays, or in the case of the Pope, edicts.

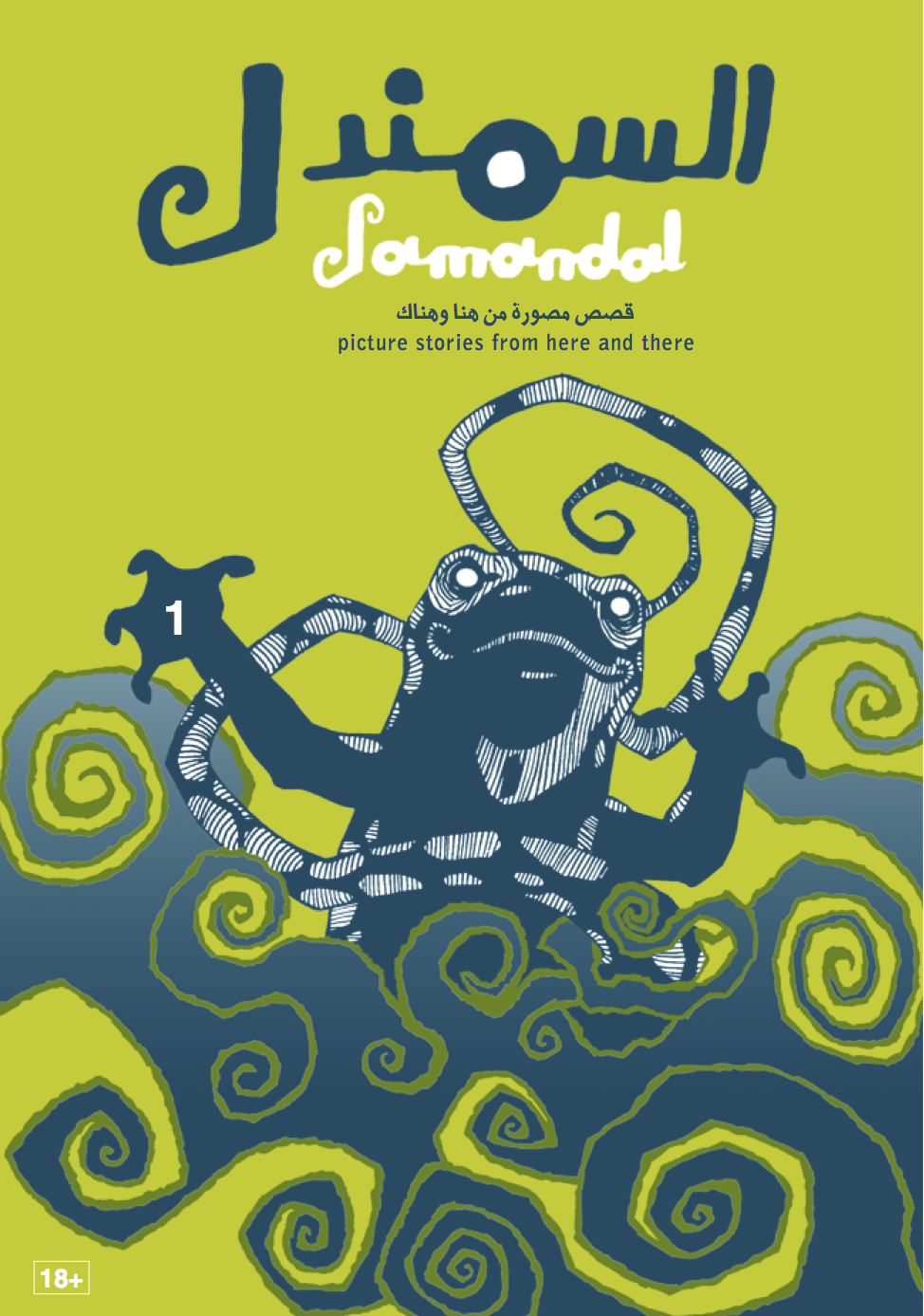

In the premier issue the staff offers an answer to “What is Samandal?”

In the premier issue the staff offers an answer to “What is Samandal?”