The following post is a barely updated version of a paper I presented at the International Bande Dessinée Society in London in 2007, entitled “Fabrice Neaud’s Face Work.” What drove the paper was two combined hunches, that 1) comics are generally concerned with, and comics are the newest instantiation of, masks as a social phenomenon (presentation of self, social roles, etc.) and 2) Fabrice Neaud’s unique focus on his face, and the faces of others in his autobiographical comics, is essentially a kind of “face work” an artistic effort to portray his “self” through a work on his “face.” I’m not sure how successful my argument was, and it may seem out of date at this point, but I have been thinking about autobiographical comics in more depth lately and I continue to believe that “face work,” while not unique to the comics art form (Proust, for example, was a master of face work while a certain number of comics artists, of course, avoid the face as a focal point), is nonetheless intimately bound to comics as an art form. If this essay seems out of date or irrelevant, I hope, at the very least, that it will encourage readers to become intimate with Fabrice Neaud’s Journal and, eventually, that editors will consider publishing an English translation. It is, from my point of view, one of the greatest works of autobiographical comics that has been published to date, certainly up there with David B’s masterpiece, L’Ascension du Haut-Mal (1996-2003).

_________

Fabrice Neaud’s autobiographical project, Journal, spans 765 pages total, covering the period of Neaud’s life from February 1992 to July of 1996 with a fifth volume that Neaud finally decided not to publish. What distinguishes this project from other autobiocomix is the fact that Neaud conceives of it as a journal. There is no preconceived unity to the project, no preconceived end. Unique to French BD at the time, Neaud is uncompromising in representing his sexuality. Also, there is a very persistent meta-bd level of discourse throughout the Journal, a constant interrogation of the conditions of representation, which makes Neaud’s work interesting for any scholar interested in the question of autobiocomix.

The title of this conference, The Innovative Form, inspires all manner of questions about the novelty of the medium. To begin with, “what’s new in BD?” that is to say, what new kinds of things are happening in the medium, but also “what’s new about BD?” that is to say, what is the potential of this form? But of course these two questions are dialectically related: we need innovations in the form before the potential of the medium itself can be fully realized. And I think Fabrice Neaud has some interesting points to make on the question posed by the title of this conference. His own discourse about BD both asserts optimistically the potential of the form and maintains a cautious provisionality as he works to reveal the potential of BD to do new things. In the fourth volume of his Journal he writes the following:

Dans le meilleur des cas, ils [les post-modernists] nous feraient même croire que la bande dessinée est le dernier refuge du dessin académique. Je ne me sens pas pour l’heure capable de démontrer le contraire. Mais j’ai bien l’intuition qu’il s’y passe autre chose, une autre façon de percevoir le réel. Une nouvelle manière de hiérarchiser les souvenirs. (Tome IV)

[In the best case scenario, they (post-modernist academics) would have us believe that comics are the last refuge of academic drawing. For the moment, I am not in a position to prove the contrary. But I sense that something else is happening here (in comics, as an art-form), another way of perceiving the real. A new way of classifying and prioritizing memories. (Volume 4).]

Neaud asserts that the potential of the form lies in its capacity to give a new and singular mode of access to the real. In the case of his own Journal, the question of perception of the real is directly connected to the enterprise of autobiographical self-representation, to the “real” of Neaud’s own life. For Neaud the mode of representation must always remain in a kind of dialectic with the “real” of the “represented,” in this case, his life. Or to put it otherwise, the work he does with the constraints and potentialities of this mode of representation is also part and parcel of a certain work on the self. He explains this process in an interview with Jérome Lepeytre:

Ainsi le journal est-il, en plus d’etre un simple témoignage ou compte-rendu d’un vécu, d’une experience, d’anectotes, un travail formel qui interroge les moyens qu’il se donne et le medium qu’il utilise: la bande dessinée: C’est un laboratoire: laboratoire sur le “moi”, laboratoire sur la vie et laboratoire formel allant jusqu’a utiliser des contraintes “oubapiennes” quand j’en ressens la nécessité.”

[Thus my journal, beyond simply being the account of a life lived, or of a personal experience, or of anecdotes, is a formal work that interrogates its own means of representation and its own medium. Comics are a kind of laboratory, a laboratory of the “self,” a laboratory of life, and a formal laboratory that will go to the extreme of using “oubabien” constraints when I feel the need to do so.]

The Journal is subject to a certain kind of work. More to the point, Neaud conceives of the journal as a laboratory. This is a very strategic choice of words here. A laboratory is a place where work and experience (and I’m thinking of the double meaning of the word expérience in French) come together to produce new perceptions of the real. I also want to underline Neaud’s use of the word travail, because this is where my reading of his Journal begins. For Neaud, it is only through the painful process of work, through an intense engagement with representation, that BD will be able to reveal its novelty, its potential to provide any kind of new access to the real. In the same interview, when trying to describe the singularity of his project, (the open-ended nature of a journal as opposed to an autobiography) he uses the English expression, “enfin, c’est un work in progress … les outils qui servent à l’élaboration du projet sont élaborés au fur et à mesure des besoins de ce projet.” He insists on underlining the contingent and improvisational nature of the project, using a language that makes one imagine Neaud’s work on the journal more along the lines of manual labor. Further on, Neaud describes the way in which the project of the journal has altered his way of “taking notes” sur le vif. Whereas he began by drawing from a written journal, supplemented by photos and a sketchbook (“carnet de croquis”), the work of the Journal has brought him to begin “thinking” within the representational constraints of the form. This is how he describes the process:

C’est-à-dire que nous n’y avons plus simplement des croquis accompagnés de notes écrites, mais bien un prédécoupage direct en sequences, quitte à ce que celui-ci soit extremement sommaire et ne se charge que de légender des cases parfois vides. Ce travail de notes me permet au moins de penser en bande dessinée. Il me parait important de souligner ici ce qui est à l’oeuvre: le travail de la bande dessinée.

[In other words, we are no longer dealing with sketches accompanied with written notes, but rather a direct pre-breakdown into sequences, even if it is true that such a pre-breakdown is cursory and is concerned with not much more than the labeling of often empty panels. This work of note-taking allows me, at the very least, to think in comics. It seems important to me to underline what is at stake here: the work of comics.]

For Neaud the work proper to BD, “le travail de la bande dessinée,” is a way of thinking in the form “penser en bande dessinée,” and it is a working towards the realization of the medium’s potential to reveal a different perception of the real. His description of his work method makes it clear: Neaud’s own perception of reality is filtered through the medium – his initial representations of recent memory are already distributed into panels. As he works on the journal, it works on him.

This “work” then happens in the journal across a broad range of representational fields: rhythm, place, word-image relation, register, symbol.

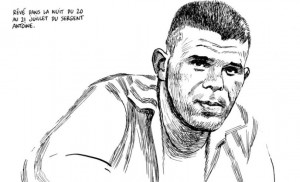

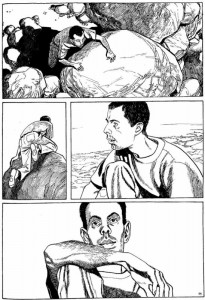

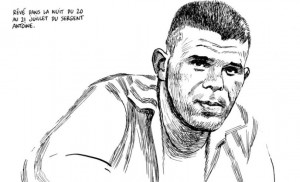

What I would like examine here is Neaud’s work on the face. There is a marked, idiosyncratic, kind of work being done on both the autobiographical face and the face of the love object (called “image” when it is the face of the other) in his Journal. [We might even say that this is the signature of Neaud’s work, this attention given to the face]. It is a kind of work that takes place both on a verbal and visual register. And it is a work that is engaged with the possibility of representing the real of Fabrice Neaud’s life. The face asks, it interrogates, the question of the real. Thierry Groensteen in his preface to vol. I of the Journal refers to Neaud as a face, as “ce visage qui nous interroge” [“this face that questions us”]. What kind of access to the real of the life of Fabrice Neaud does the face of Fabrice Neaud give us? While his more or less realistic (as the French would say, “classique”) style of drawing would seem to promise a relatively straightforward autobiographical representation, the particular attention he gives to his own face, suggests he is concerned with the way the autobiographical face might authenticate self-representation (like a signature), and thus complicates the presumed simplicity of self-representation.

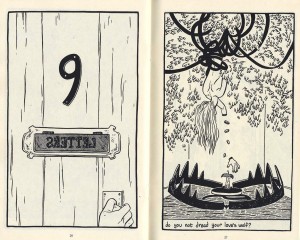

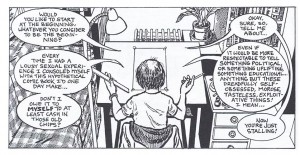

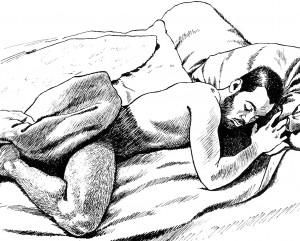

We have from the very first pages of volume I of the Journal a complex discourse on the face. When he writes about his nocturnal sexual encounters in the jardins publiques, he criticizes the safe hypocritical anonymity of the kinds of sexual encounters that take place there, encounters that happens without face. Neaud claims to refuse the anonymity of faces, “je refuse l’anonymat des visages” [“I refuse the anonymity of faces”]. And a few panels later, “je tiens à assumer jusqu’au bout: circuler à visage découvert sans être obligé aux clichés que ceux qui viennent … se sont imposés à eux-même” [“I am committed to claiming my identity to the extreme, to circulating with an exposed face, without being forced to acquiesce to the faces that those who come [to the cruising park] have imposed on themselves”]. Neaud’s discourse on the face is haunted by a metaphorics of masks. As he explains it, while he claims to show his “true” face, in other words to fully assume his homosexuality, he nonetheless also refuses to “wear the mask” of gay clichés. But this is hard to do when faced with an insistent deontologizing heterosexual gaze, a gaze that itself imposes masks on its other. Confronted daily with a heterosexual gaze, he steadfastly refuses to present a legible face – refuses to provide a comfortable or digestible face for the other to have a (faux) ethical encounter with.

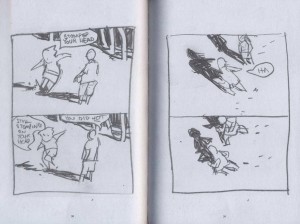

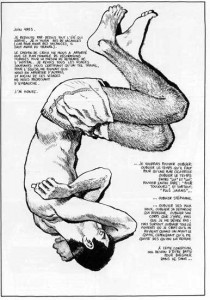

The legibility of the homosexual face is presented as a question in the opening pages of the Journal. A sort of “flash back,” the scene takes place in a park, 1975, where the young Fabrice is chased and violently forced to pull his pants down to “show that he’s not a girl.” [And here already at the beginning he is very deliberate in his representation of the face]. This primal scene of the journal returns to haunt another scene that takes place, significantly, also in a park. Discussing his nocturnal wanderings, describing the various types of men who frequent the park in an anthropological (or almost more zoological) manner, Neaud describes a certain type of married man who frequents the park. A set of four panels show a faceless, anonymous man, presumably a married man seeking easy sexual gratification in the safety of his car. When Neaud refuses him, the man insults him, calling him “pédé” [“faggot”]. The insult, is both an interpretation, that is, a reading of the face, and an interpellation, that is, a giving of face. Here he compares these faceless men to his childhood bullies:

Ce sont eux. Ce sont les mêmes qui me traitaient de “tapette” alors qu’ils ne savaient même pas ce que ça voulait dire … tout simplement parce que je n’aimais pas leurs jeux … Ce sont les mêmes qui m’ont fait tant douter quand “tapette” je suis devenu, et que j’ai cru qu’à m’insulter de la sorte … ils l’avaient lu sur mon front.

[“Those are the ones, the same ones who called me a queer even though they didn’t even know what that meant… just because I didn’t like their games… the same who made me doubt myself when I did become queer and who, in insulting me thus, convinced me that they had read it on my forehead”]

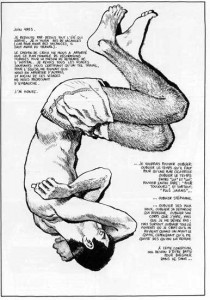

[Neaud is haunted by the thought, this childhood conclusion, that his homosexuality is “written on the face.” And here we have a rewriting of the primal scene in which he gets up from of his abject (fetal) position and faces his interpellators returning the insult… But although he able to rewrite the scene and “face” them, his face here is scratched out, de-faced. Why does he do this here? At least one way to read this is as part of a general project to render his face illegible in the face of this interpellation of the heterosexual gaze – here the gaze and the insult are one and the same, by the way]

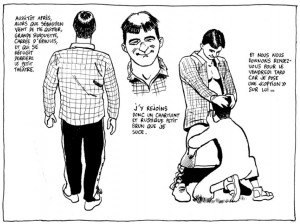

And this is a general condition of Neaud’s life, both in private and in public, he finds himself fighting constantly against the deontologizing tendencies of the straight people in his milieu. Even his “liberal,” non-homophobic friends expect Neaud’s work to “reveal” a certain truth about homosexuality (the word dévoiler (reveal, unveil) is used a lot in relationship to the word pudeur (prudishness) as though only Neaud, the only gay person in the association, must bear the sole burden of confronting societal taboos). His friend and collaborator Loïc Néhou, now the general editor Ego Comme X, suggests that Neaud might tell the story of his “petites ballades nocturnes” [“little nighttime excursions”]. In a rather funny scene that takes place in Journal IV, Neaud depicts a radio interview in which the radio announcer claims that the subject of his journal is “homosexuality.” Neaud responds violently.

“Sinon, faut dire quand meme que ton sujet principal, c’est l’homosexualité. T’as un message à faire passer? // Je n’ai aucun message à faire passer sur l’homosexualité!! Il n’y a plus grand’chose à dire sur l’homosexualité!! Est-ce que Roméo et Juliette a pour sujet principal l’hétérosexualité? NON! … Je parle de mon quotidien … // […] Et mon sujet principal, c’est plutôt … le portrait de mon modele: “Stephane”!

“In any case, your main subject is homosexuality. Do you want to convey a message [to my listeners]?” / “I don’t have any message to convey about homosexuality. There’s nothing left to say about homosexuality!! Is heterosexuality the main subject of Romeo and Juliette? NO!!! I just write about my daily existence… and my primary subject is more precisely that of my model, Stephane.”

So I would suggest that Neaud’s work on the face resists presenting any kind of intelligibly gay subject, and in resisting the imposed “masks” succeeds in presenting a new perception of the real. In effect, all of Neaud’s most intense face work appears in the chapters of his Journal most explicitly concerned with the question of gay identity. His resistance to and cynicism towards the autobiographical signature is finally impossible to separate from his refusal to produce the effect of an intelligible gay identity in his autobiographical Journal.

On a visual level, the face-work occurs in a number of different modalities. I will describe four of those modalities, although there would be many more, and these could and should be further nuanced:

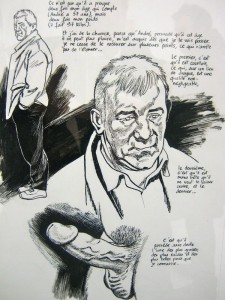

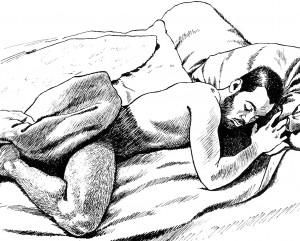

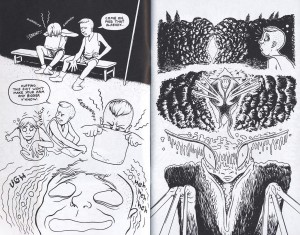

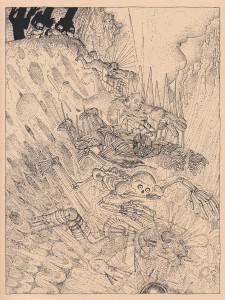

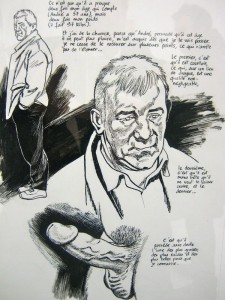

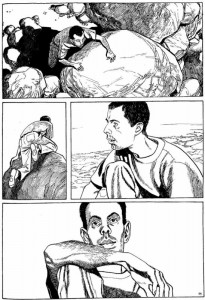

1) The photographic punctum, the “snap” photo effect. Neaud does not hide the fact that he works off of photographs to draw himself and those in his entourage. In fact, in all four volumes of the journal he shows himself photographing those around him. Also at various moments we see him sorting through his archive of slides and printed photographs. In one very memorable panel, he shows himself projecting a slide of his love object. He stands inside of the projection so that his face is distorted, almost monstrously, by the image of his love object’s face projected onto and overlapping with his own. But it is not just through the narrative that we learn about his use of photographs. We can also see it very clearly in his drawing of the face, from his choice of photographs to draw from… Neaud uses a lot of bad, “snap” photography, in which eyes are closed, the face is caught awkwardly in the moment, or made to appear monstrous through unflattering angles, bad lighting, flash, etc.

But why incorporate the photographic into his face work when photography would seem to only reflect the deontologizing gaze of the other? In other words, all of the photos Neaud uses to draw of his own face were taken, that is framed, by others. If Neaud is working to resist the heterosexual gaze, making his face illegible, as I’m claiming here, why use photography? I think the answer lies in the way he uses photography – using it in such a way as to refuse to suture the inhuman eye of the lens. So more than using photography, he marks this use in interesting and even radical ways. By choosing bad, unflattering, snap photos, the autobiographical face is made ugly, not through a process of distortion but on the contrary through the photographic process of representing too faithfully. Making reference to the inhuman eye of the camera lens is one way of resisting the appropriative gaze of the other, because it reveals the extent to which that gaze is subjectivized. It’s like he’s saying “yes, you ultimately frame me, but I can also continue to remind you that you are doing this, that this is not a “natural” process but rather an imposition”. The bad snap shot also highlights the dramatic fleetingness of the moment (rather than “capturing” the moment, the bad snap photograph marks the moment as “past” “dead” already lost… etc. therefore there is no “face” that could be said to transcend time, etc.).

2) Defacement: At various moments throughout the journal, Neaud defaces himself, erasing parts of his face (his mouth or eyes or both), rubbing out his facial features so the face is smudged, scratching it out, or leaving it blank. This is a more “obvious” way of rendering the face illegible and I interpret this particular mode of face work in the vein of a refusal. By defacing the autobiographical face, Neaud is simply saying “no” every time the reader might need or want the attenuation of a face.

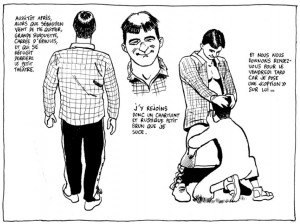

3) Displacement, metonymy: Another modality of face-work could be called the displacement of the face. There are a number of scenes in which the rhythm of the panels creates the expectation of a face when we have, appearing in its place, something else, another body part, a concrete object, a blank panel, sometimes enacting a complete shift of representational orders (like going from faces to mathematical formulas, which occurs in a few panels)… The use of other parts of the body – such as the back of the head or of a hand, or in one case a stomach –where his face is expected.

4) Mask, prosopopeia: the trope of the mask (highly specific to the form and history of comics) in Neaud’s Journal includes his use of caricature, borrowings of representational modes (such as that of Francis Bacon), and his self-consciously recycled repertoire of facial gestures. As much as he claims to “circuler à visage découvert” [“circulate with an exposed face”] he also reminds the reader that there is a process of “masking” that happens in the writing of the journal (a kind of medieval idea, masking in order to unmask, in order to show the true self … this could be said in a way to be the most important aspect to his process of self-representation … and also points to something specific about bande dessinée, that if there were a master trope of bd, it might be said to be prosopopeia, the trope of the mask, the talking mask.)

Rather than concluding, I’d like to gesture towards a more critical reading of Neaud [more critical of Neaud, I mean] that would have to do with a different kind of face-work — his work on the faces of others, and more specifically the faces of his love objects (namely Stéphane and Doumé). Recall the radio interview, when Neaud angrily denies that the subject of his journal is homosexuality, he suggests instead that the true subject is more likely his love-object, or as he puts it “Et mon sujet principal, c’est plutôt … le portrait de mon modèle: “Stephane”! [this is in reference to volume one]. I think his use of the word “portrait” (which implies the representation of a face) is significant here. I suspect that his work on face of the other ultimately comes to obscure his work on the autobiographical face. On a purely visual level, his work on the face of the love object (esp. in vols 1 and 3) is most elaborate. He works more on the face of the other. Both on the visual and verbal levels. He deflects the deontologizing gaze of the other by intensifying (and justifying) his own.

_______

I’m sorry to recycle old work but I also hope that there might be some useful nuggets for those interested in autobiographical comics who might not have access to the franco-belgian tradition.

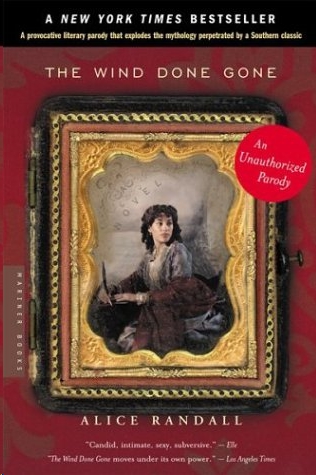

Alice Randall’s “The Wind Done Gone” is superior to the Margaret Mitchell novel it is based on in many respects. Though Mitchell’s prose is quite good, Randall’s is better , earthier and more poetic at once (“It’s a pissed bed on a cold night to read words on paper saying your name and a price.”) Randall’s economical, short book also avoids Mitchell’s tendency to ramble. But perhaps most surprising in a sequel/parody, Randall’s book makes more sense.

Alice Randall’s “The Wind Done Gone” is superior to the Margaret Mitchell novel it is based on in many respects. Though Mitchell’s prose is quite good, Randall’s is better , earthier and more poetic at once (“It’s a pissed bed on a cold night to read words on paper saying your name and a price.”) Randall’s economical, short book also avoids Mitchell’s tendency to ramble. But perhaps most surprising in a sequel/parody, Randall’s book makes more sense.