“The true picture of the past flits by. The past can be seized only as an image which flashes up at the instant when it can be recognized and is never seen again. ‘The truth will not run away from us’: in the historical outlook of historicism these words of Gottfried Keller mark the exact point where historical materialism cuts through historicism. For every image of the past that is not recognized by the present as one of its own concerns threatens to disappear irretrievably.”

–Walter Benjamin, “Theses on the Philosophy of History” (English translation Harry Zohn; Illuminations p. 255)

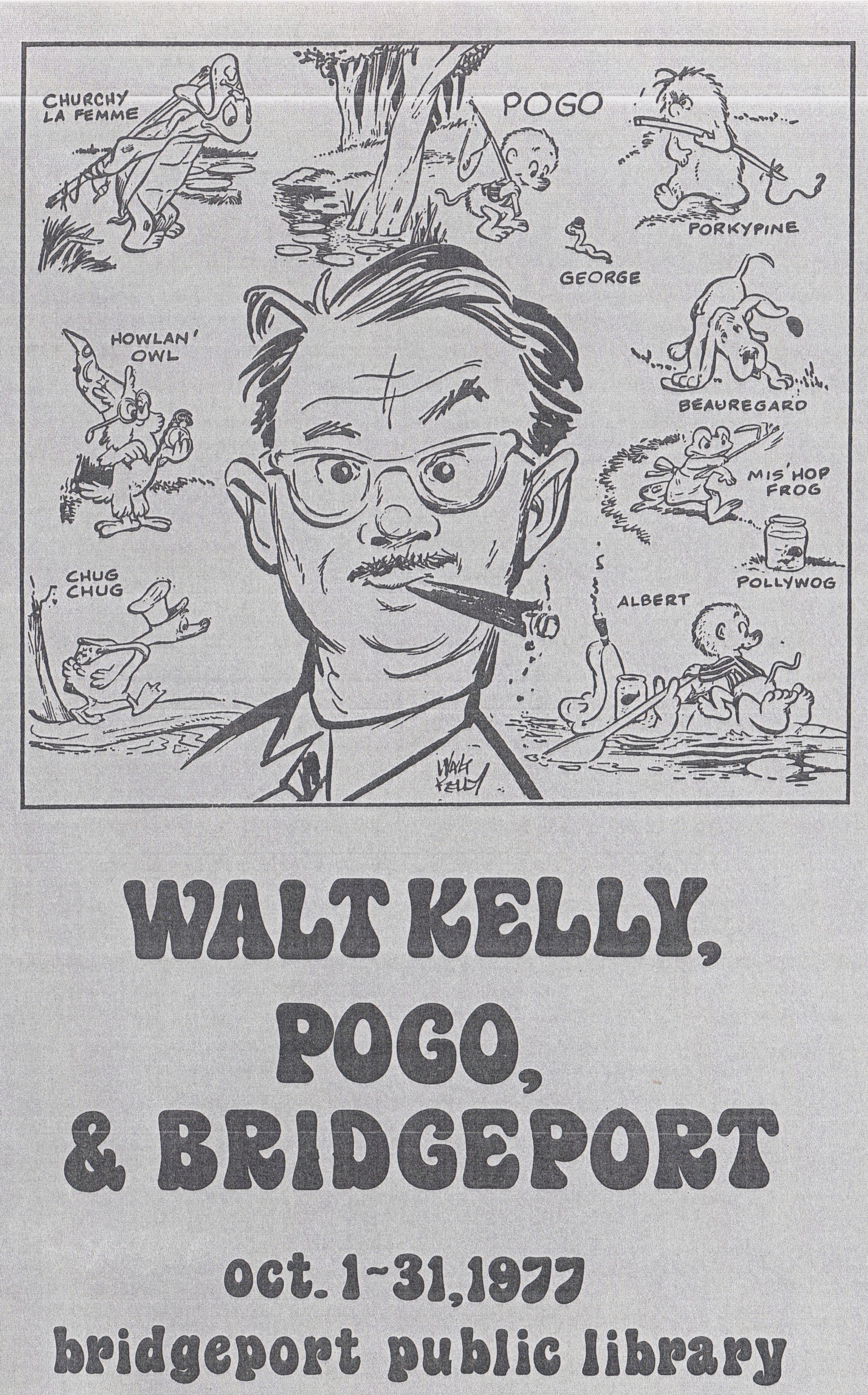

Fig. 1: Clipping courtesy of the Bridgeport History Center at the Bridgeport, Connecticut Public Library

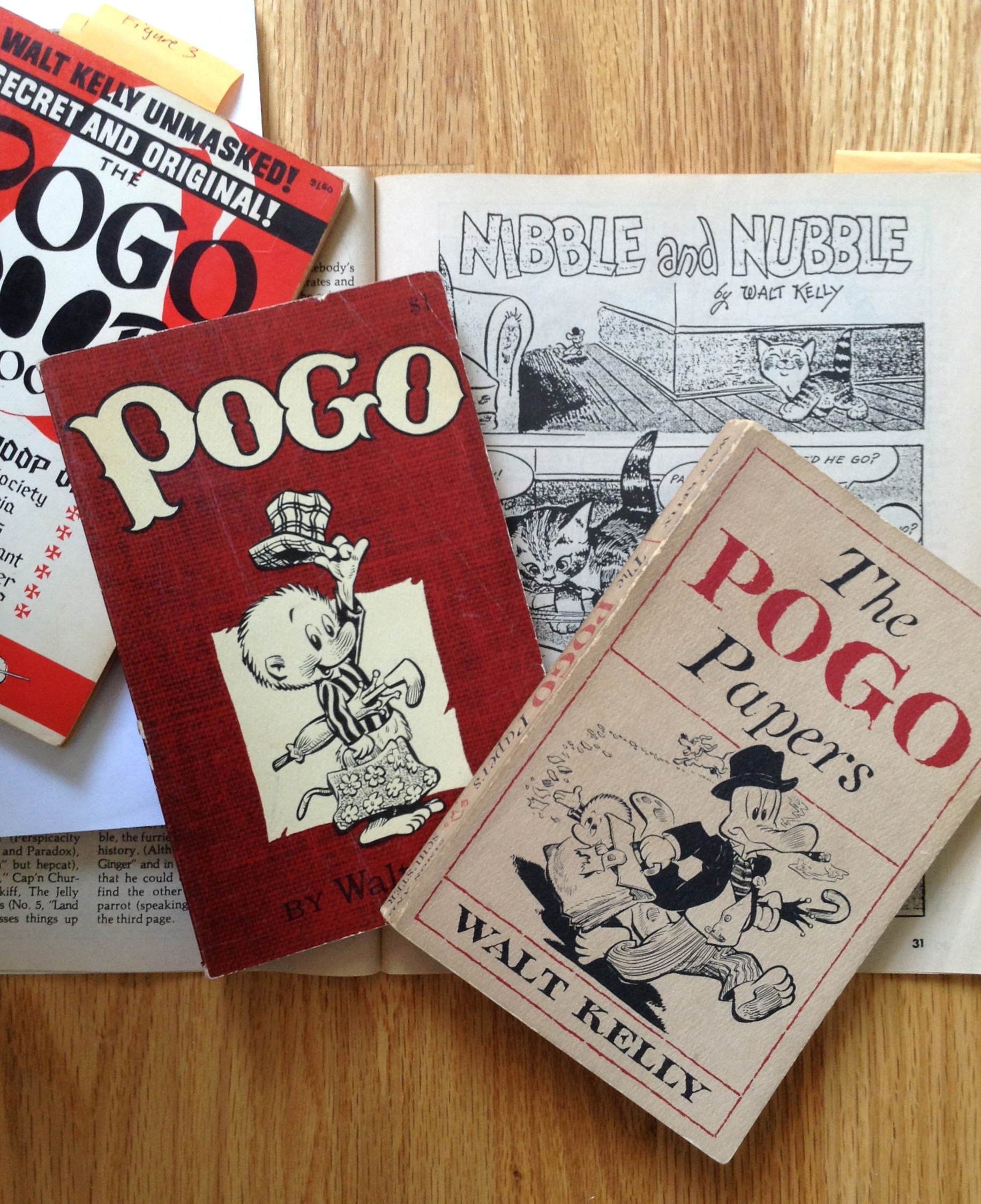

I wonder sometimes if I’m being followed. I can’t seem to escape from Walt Kelly. R. Fiore’s recent TCJ review of the new Hermes Press collection Walt Kelly’s Pogo: The Complete Dell Comics Volume 1, compels me once again to consider the cartoonist, who died in 1973 and lived his formative years in Bridgeport, Connecticut. The Park City is about thirty miles south of Oakville, my hometown, and Oakville is just outside of Waterbury, where the Eastern Color Printing Company began producing comic books in the 1930s. Of course, I’d heard of Kelly long before I’d read any of his work. He’s on a short list of Connecticut luminaries, along with Nathan Hale, Rosalind Russell, Paul Robeson, and Thurston Moore, but I didn’t read Kelly’s celebrated strip until I was in my mid-thirties. Several years ago, one of my students gave me copies of two of her late father’s beloved Pogo collections. I know you enjoy comics, she said, and you teach them, too, so I think you might like these: Pogo, the first Simon and Schuster collection from 1951, and The Pogo Papers, from 1953. Covers creased, paper tan and brittle, bindings cracked. Her dad, I know, loved these books, returned to them, left them behind for his daughter, for me. I thanked her for this kind gift, but even then, in the summer of 2007, I neglected them. A year later I was asked to contribute an essay to a collection on Southern comics and I remembered what my student had said: You might need these. I think that’s what she said. I’d like to think so, anyway.

I begin with what is probably more than you need to know about me and Walt Kelly because, like Fiore, I, too admire the artist, and, in the years since my student handed me her father’s Pogo books, I’ve written about his work twice: first, in an essay on Bumbazine for Brannon Costello and Qiana Whitted’s collection Comics and the U.S. South (UP of Mississippi, 2012) and again last year for a paper presented at the Festival of Cartoon Art at the Ohio State University’s Billy Ireland Cartoon Library and Museum. In the first essay, which Tom Andrae cites in his introduction to the new Dell Comics collection, I discuss the two scenes Fiore addresses in his review— the watermelon panel from “Albert Takes the Cake” (Animal Comics #1, dated Dec. 1942-Jan. 1943) and the railroad sequence from “Albert the Alligator” (Animal Comics #5, dated Oct.-Nov. 1943). You can read that 2012 essay, “Bumbazine, Blackness, and the Myth of the Redemptive South in Walt Kelly’s Pogo” here or from your local library; the Google Books version does not include the illustrations.

Fiore takes issue with Andrae’s analysis of the black characters who appear in “Albert the Alligator.” While he begins with the suggestion that “Andrae is on firmer ground in denouncing the characterizations in the story from Animal Comics #5,” Fiore then asks that we consider other readings of the narrative:

Once again, however, [Andrae] is sloppy in characterizing [the characters] as “derisive minstrelsy stereotypes.” The conventions of the minstrel show were as formalized as the Harlequinade, and the characters in the story at hand don’t fit them. Further, I believe a more sophisticated and context-conscious reading would come to a different conclusion.

As I read these remarks, I began to wonder, what would a “context-conscious reading” of this sequence look like? And is Fiore correct? Would it reach a different conclusion than the one in Andrae’s introduction?

I attempted just that sort of contextual reading in my Bumbazine essay, in which I trace the impact not only of minstrelsy but also of the rhetoric of the South as redeemer, a concept Kelly inherited from the Southern Agrarians. But any reading that hopes to place Kelly in historical context must take into account the tensions and fractures that exist in his body of work. Kelly is a significant cartoonist not because he was more progressive than other artists working in the 1940s but because he records for us the contradictions in his own thinking and practice.

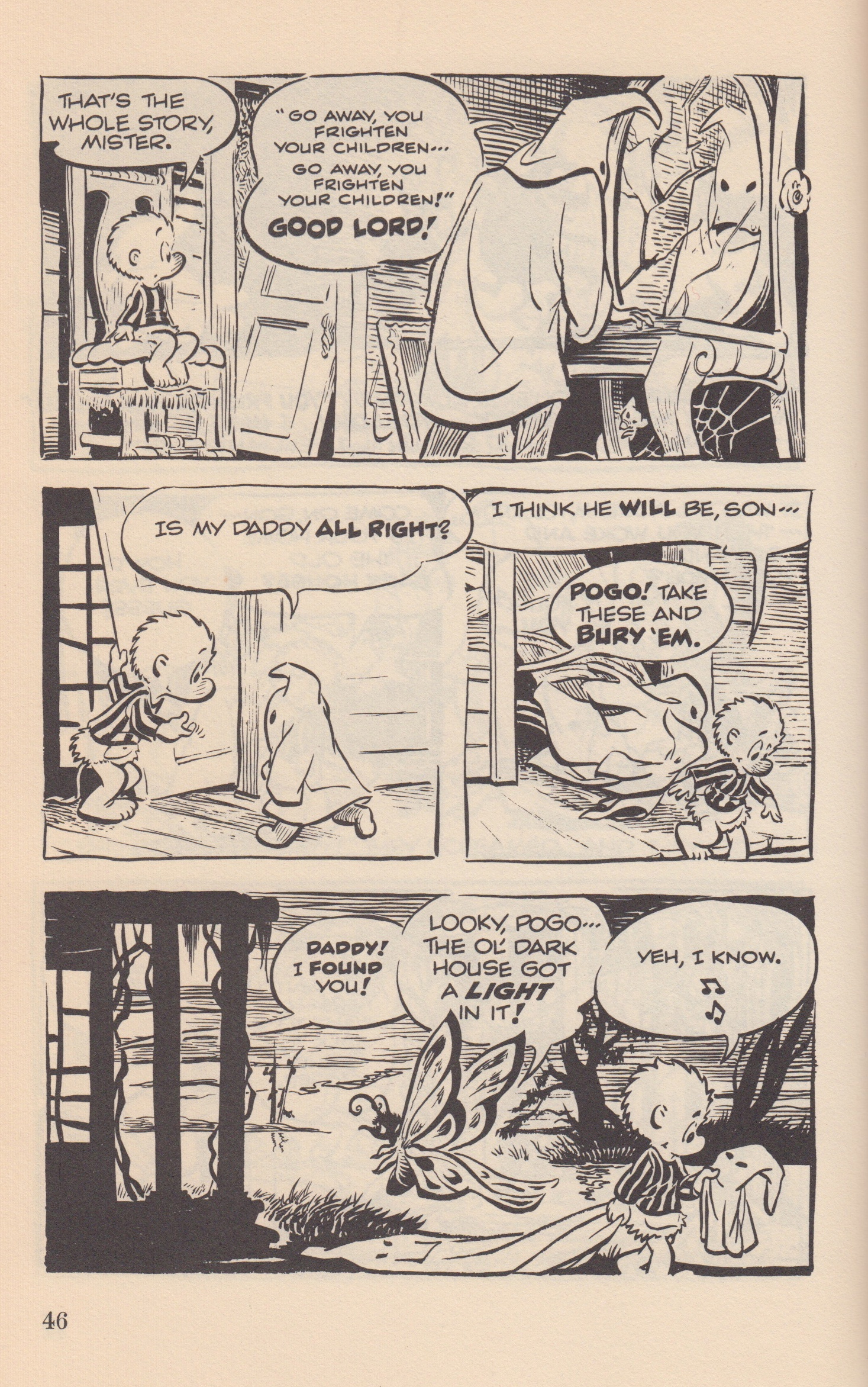

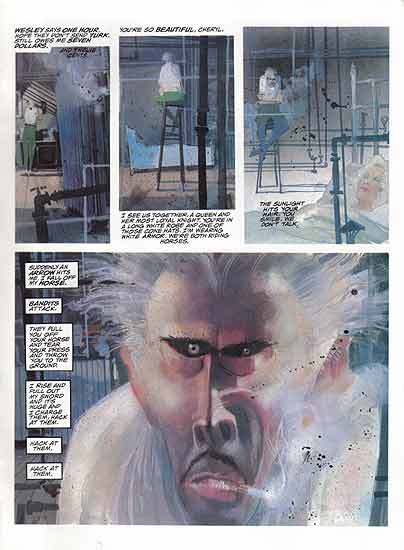

Fig. 2: Pogo takes on one of the Kluck Klams in a story from The Pogo Poop Book, 1966

Kelly, the child of working-class parents, a left-leaning, often progressive autodidact who, later in his career, would challenge Senator Joseph McCarthy, the Ku Klux Klan, and the John Birch Society, demands our attention because he forces us to ask another question: given his reputation as a cartoonist beloved by students and liberal intellectuals of the 1950s and early 1960s, how could he also have produced works such as “Albert the Alligator,” stories that clearly owe a debt to the conventions of the minstrel stage, and that traffic in derogatory stereotypes? To answer this question, I believe we need to understand Kelly’s nostalgia for his hometown of Bridgeport, Connecticut. One of the flaws in some of Kelly’s early work was his inability or unwillingness to interrogate the images and ideas he’d inherited from childhood artifacts such as, for example, Joel Chandler Harris’s Uncle Remus stories. As Andrae reminds us in the introduction to the Dell Comics collection, Kelly’s father enjoyed readings those stories to his son.

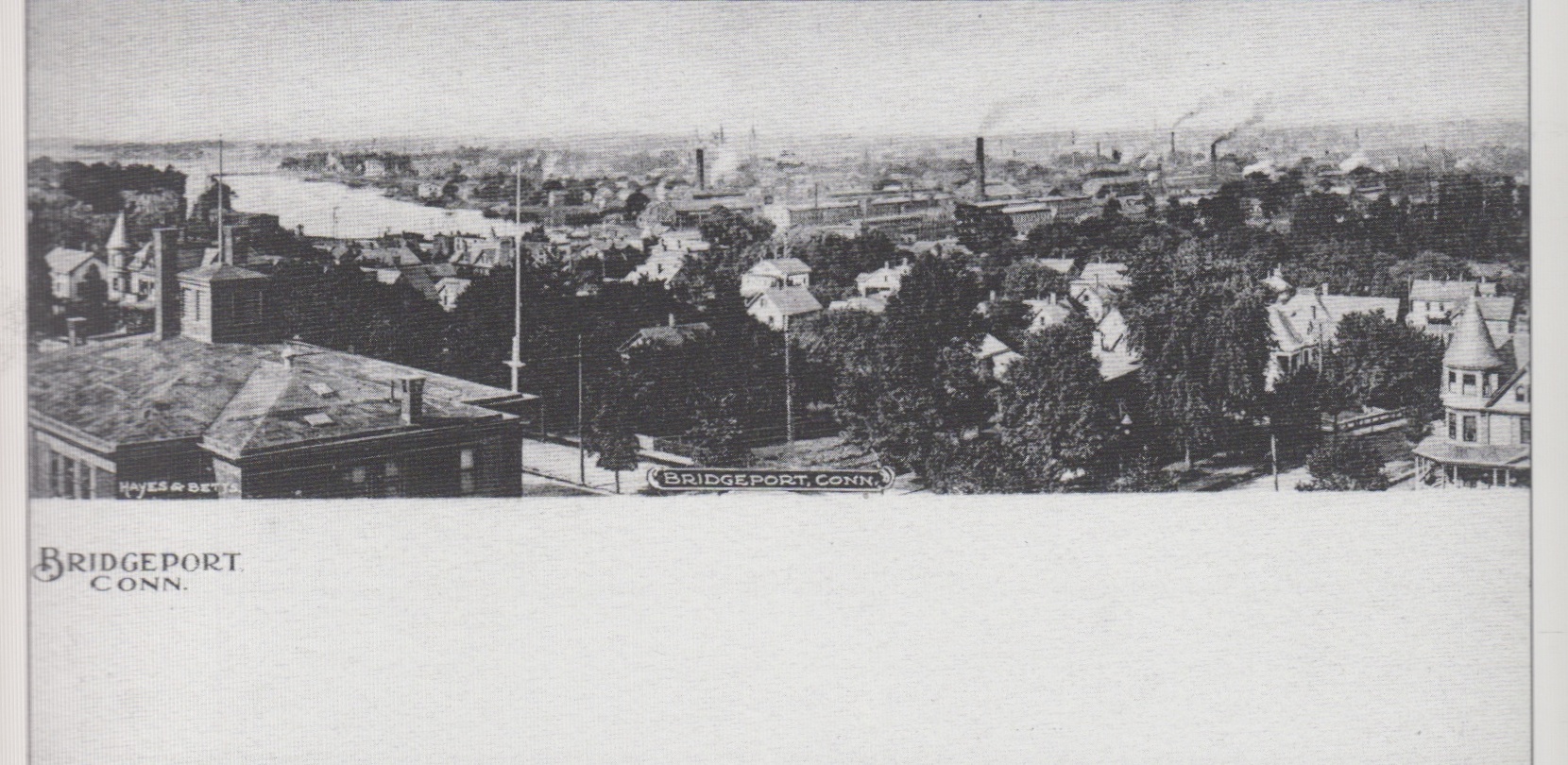

Fig. 3: Image of Bridgeport from Andrew Pehanick, Bridgeport 1900-1960, p. 124

What effect does nostalgia have on us, as writers, as artists, as critics—as fans? When I speak about Kelly, I find it difficult to separate my nostalgia for home from Kelly’s fondness for the Bridgeport of the late teens and 1920s. When I read Kelly now, I am reminded of my childhood in Connecticut, not because Kelly’s comics played any role in it, but because the setting he describes in his essays, for example—the industrial landscape of the Northeast—is also the world of my imagination. By the late 1970s and the early 1980s, however, the brass and munitions manufacturers that had attracted so many immigrants from Europe and migrants from the South were fading. The only traces that remained were signs with names like Anaconda American Brass on redbrick walls of abandoned factory buildings. And the stories, of course, of the men and women who, like Kelly’s father, like my grandparents and great grandparents, worked in those mills.

Fig. 4: My grandmother, Patricia Budris Stango, second from left, at work in 1941 at the United States Rubber Company, later called Uniroyal, in Naugatuck, Connecticut

As I argue in my essay on Bumbazine, Kelly did not write about the U.S. South. Rather, he told stories in a setting that, for all its southern trappings, looked and felt more like New England. The city of Bridgeport, Connecticut, was, in the early twentieth century, as Kelly describes it, “as new as a freshly minted dollar, but not quite as shiny. The East Bridgeport Development Company had rooted out trees and damned up streams, drained marshes, and otherwise destroyed the quiet life of buttercups and goldfinches in order to make a section where people like the Kellys could live.” In this essay from 1962, Kelly might be describing Pogo’s Okefenokee Swamp: “Surrounding us was a fairly rural and wooded piece of Connecticut filled with snakes, rabbits, frogs, rats, turtles, bugs, berries, ghosts, and legends” (Kelly, Five Boyhoods, 89).

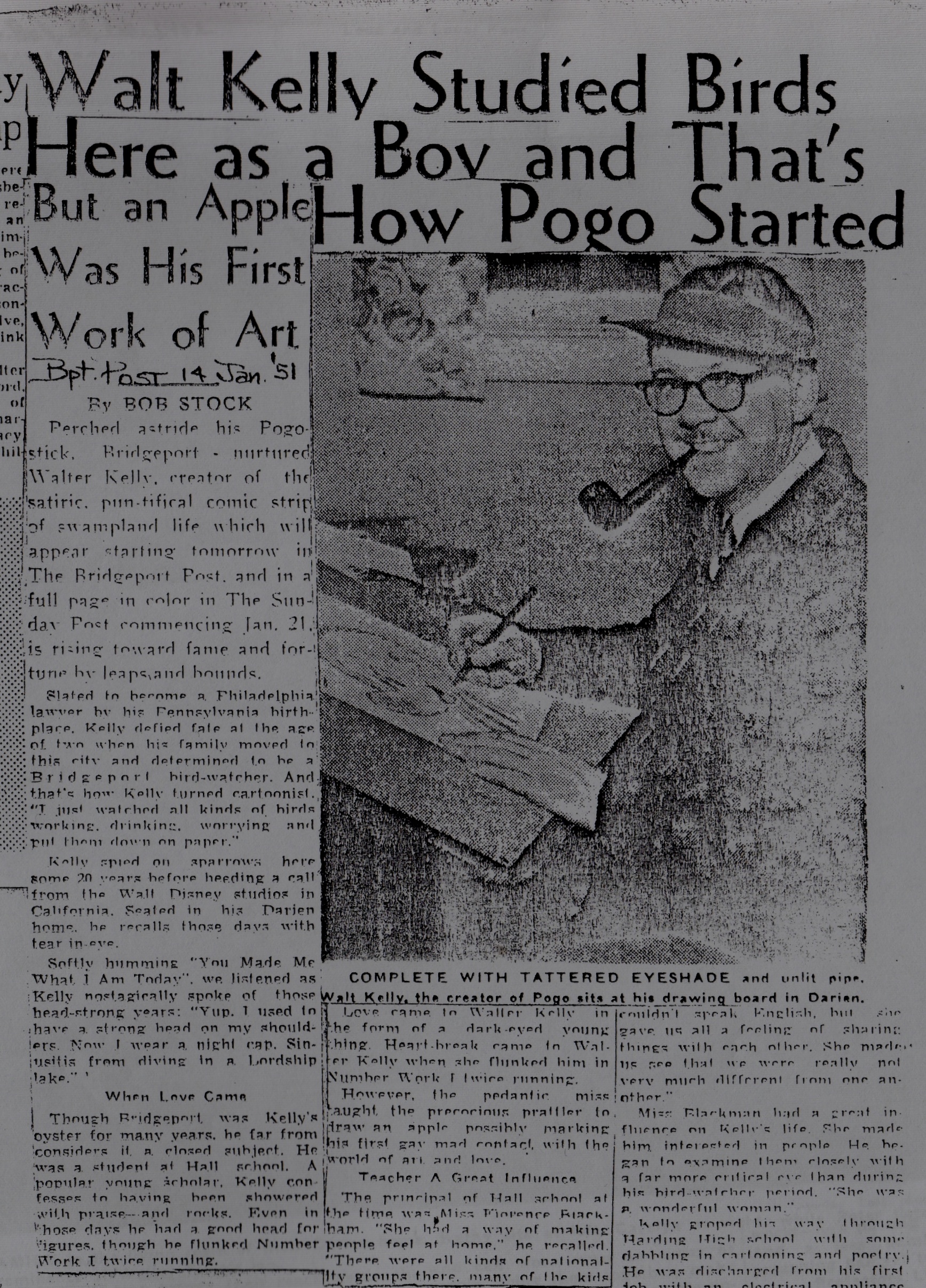

Fig. 5: Clipping from the Bridgeport Post, January 14, 1951. Courtesy of the Bridgeport History Center.

Kelly scholars from Walter Ong to Betsy Curtis to R.C. Harvey to Kerry Soper and Tom Andrae have since the 1950s been looking closely at some of these legends. In his essay “The Comic Strip Pogo and the Issue of Race”—along with Soper’s We Go Pogo (UP of Mississippi, 2012), one of the best academic analyses we have of Kelly’s strip—scholar Eric Jarvis points out that Kelly often referred to “his elementary school principal in Bridgeport as a rather nostalgic model of how society should approach these issues with ‘gentility’” (Jarvis 85). Jarvis then includes passages from Kelly’s introduction to the 1959 collection Ten Ever-Lovin’ Blue-Eyed Years with Pogo in which the artist again remembers the Bridgeport of his childhood and that principal, Miss Blackham: “Somehow, by another sainted piece of wizardry, she sent us off to high school feeling neither superior nor inferior. We saw our first Negro children in class there, and believe it or not, none of us was impressed one way or another, which is as it should be. Jimmy Thomas became a good friend and the young lady was pretty enough to remember even today” (Kelly, Ten Ever-Lovin’ Blue-Eyed Years, 6).

As Kelly biographer Steve Thompson reminded us at the OSU conference, however, in other interviews Kelly describes the racism and ethnic tensions in the Bridgeport of the 1920s. So, like Jarvis, I am fascinated by the role nostalgia plays in Kelly’s art and in his essays because, after all, as Svetlana Boym reminds us, nostalgia is a utopian impulse, a desire not so much to recover the past as it was lived but to recall the life we wish we’d lived, in a world that never was. But, if it had existed, what would that world have looked like? “Nostlagia (from nostos—return home, and algia—longing),” Boym writes, “is a longing for a home that no longer exists or has never existed. Nostalgia is a sense of loss and displacement, but it is also a romance with one’s own fantasy” (Boym XIII).

When Brannon Costello asked if I’d contribute an essay to Comics and the U.S. South, I hesitated. My first thought was to write an article on Howard Cruse and Stuck Rubber Baby. Already taken, Brannon told me. Then I asked, What about Pogo? You can’t publish a book on comics and the South without Pogo. A friend later remarked, Why would you write about the South? You lived there for less than a year, and the whole time all you talked about was New England. That’s not exactly what she said. What she said was something closer to this: You hated it there. But, more recently, when I told my friend that I’ve now written two essays about Kelly and the South, she smiled and said, Of course. The more we resist something, the more we are drawn to it. The more I resisted Kelly’s comics, the more I found myself drawn to them and to the South and to the myths of Kelly’s youth—my youth—that I had ignored

So, in reading R. Fiore’s review of the new Pogo collection, I again find myself face to face with Walt Kelly. And I keep returning to Walt Kelly’s early comics not because they transcend discourses of race; rather, I return to them because they include these stock figures and because I believe these early stories, like my student’s gift, offer an opportunity to think and to reflect on how these discourses—how these racist stereotypes—have shaped my life, my thinking, my conduct in the world. I am writing about Kelly because, to borrow a phrase from Walt Whitman, he and I were “form’d from this soil, this air,” and I turn to him because he invites me to dig through that soil, to breath the air again, to remember.

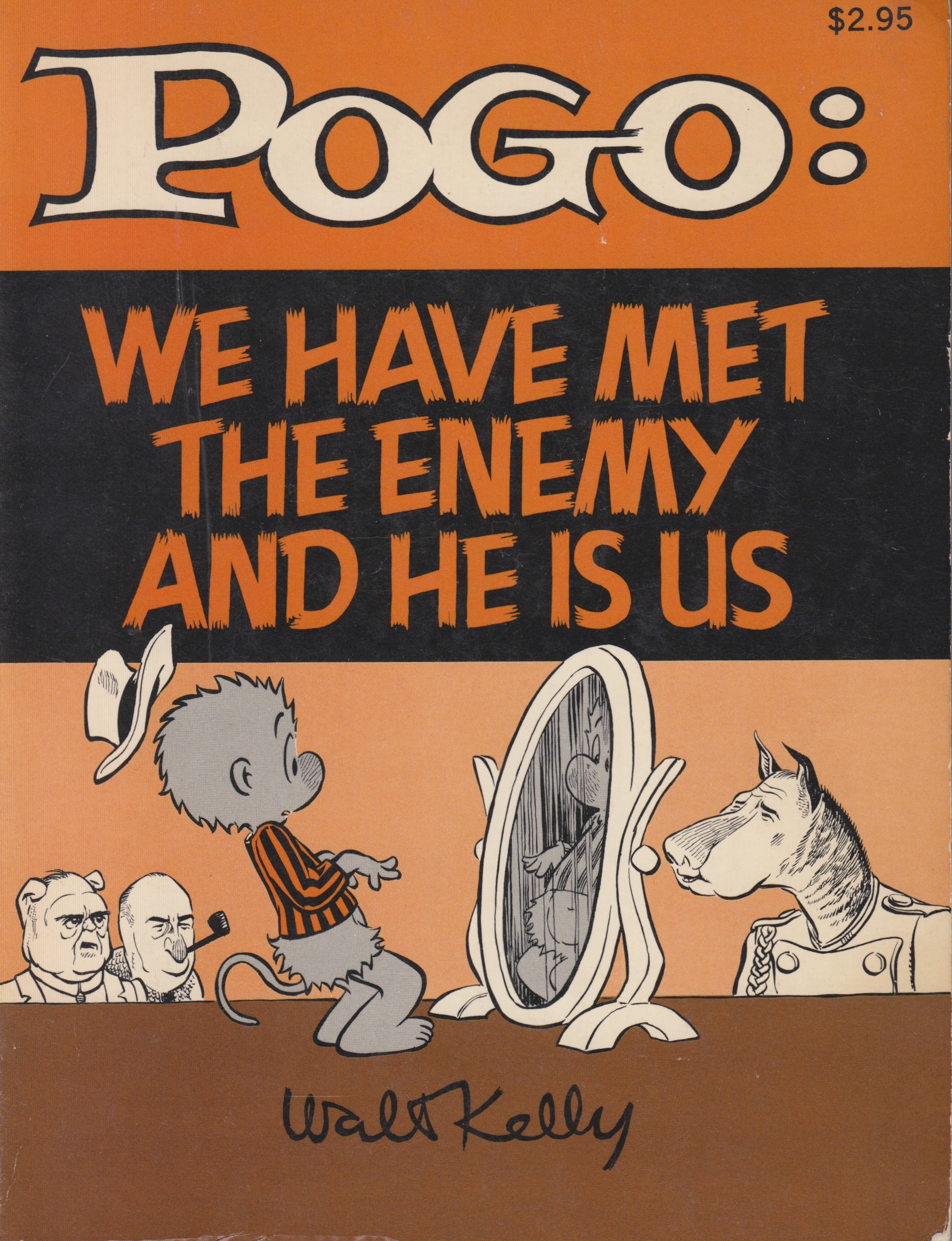

Fig. 6: The final Pogo collection Kelly published in his lifetime (1972)

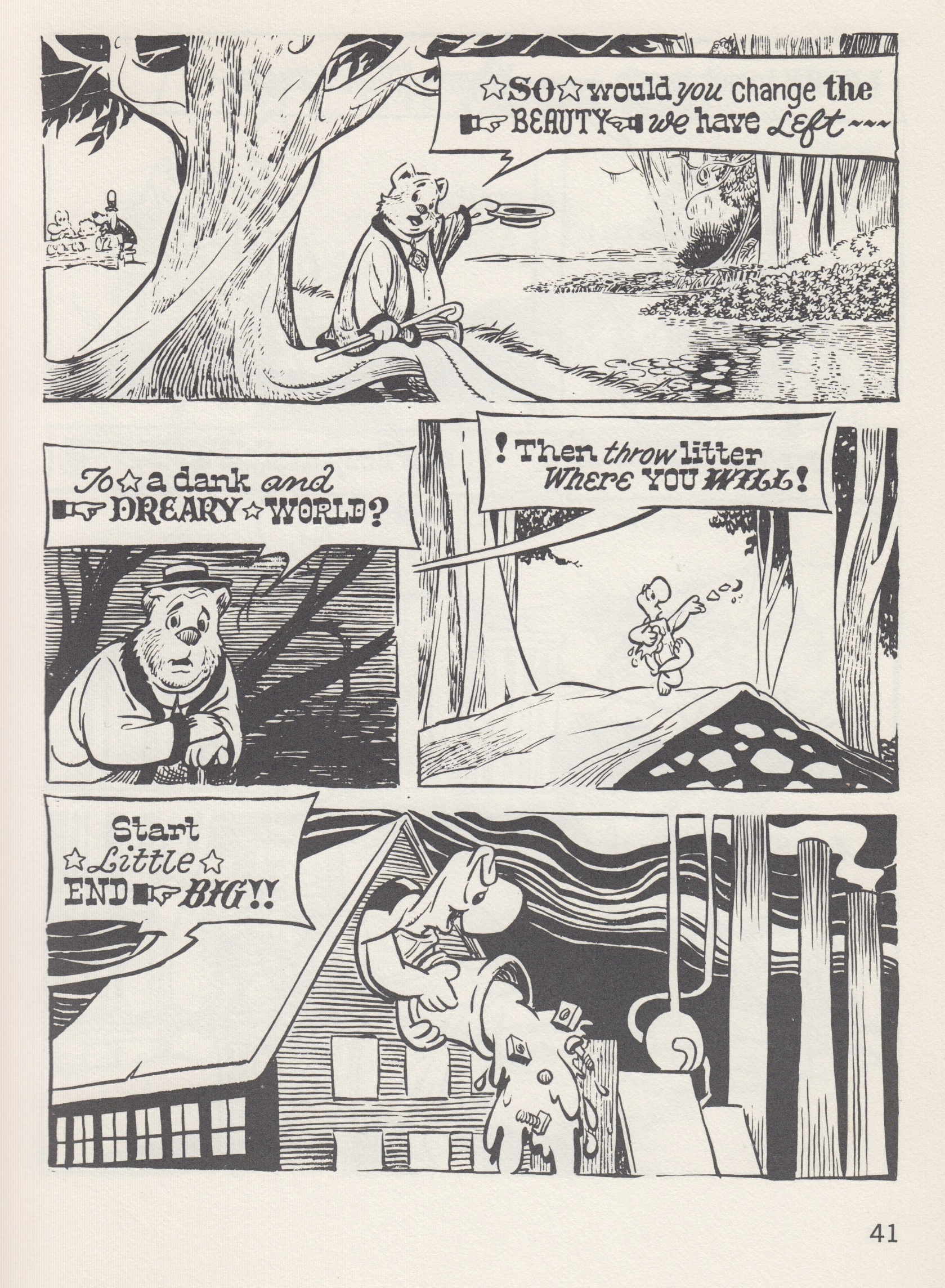

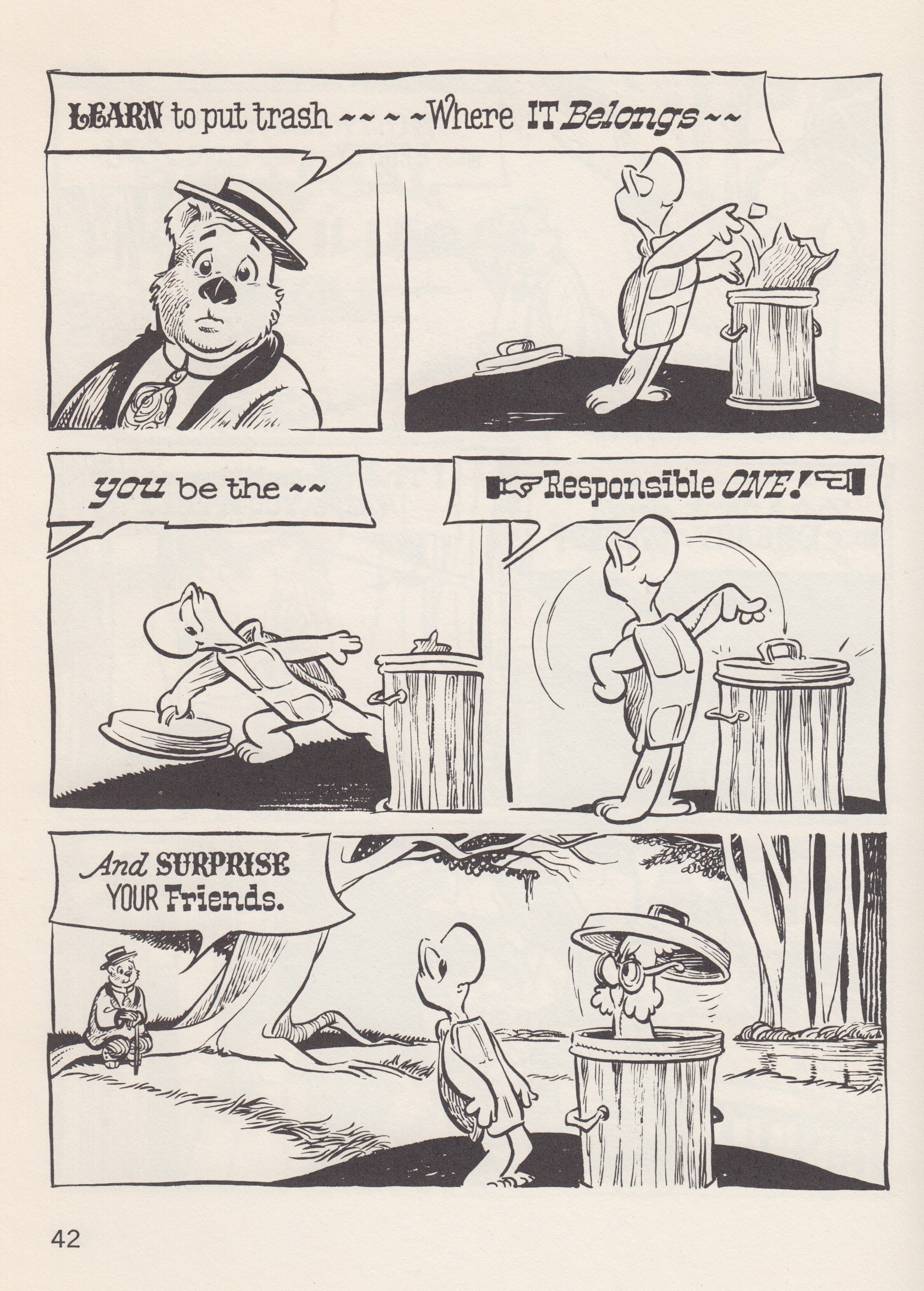

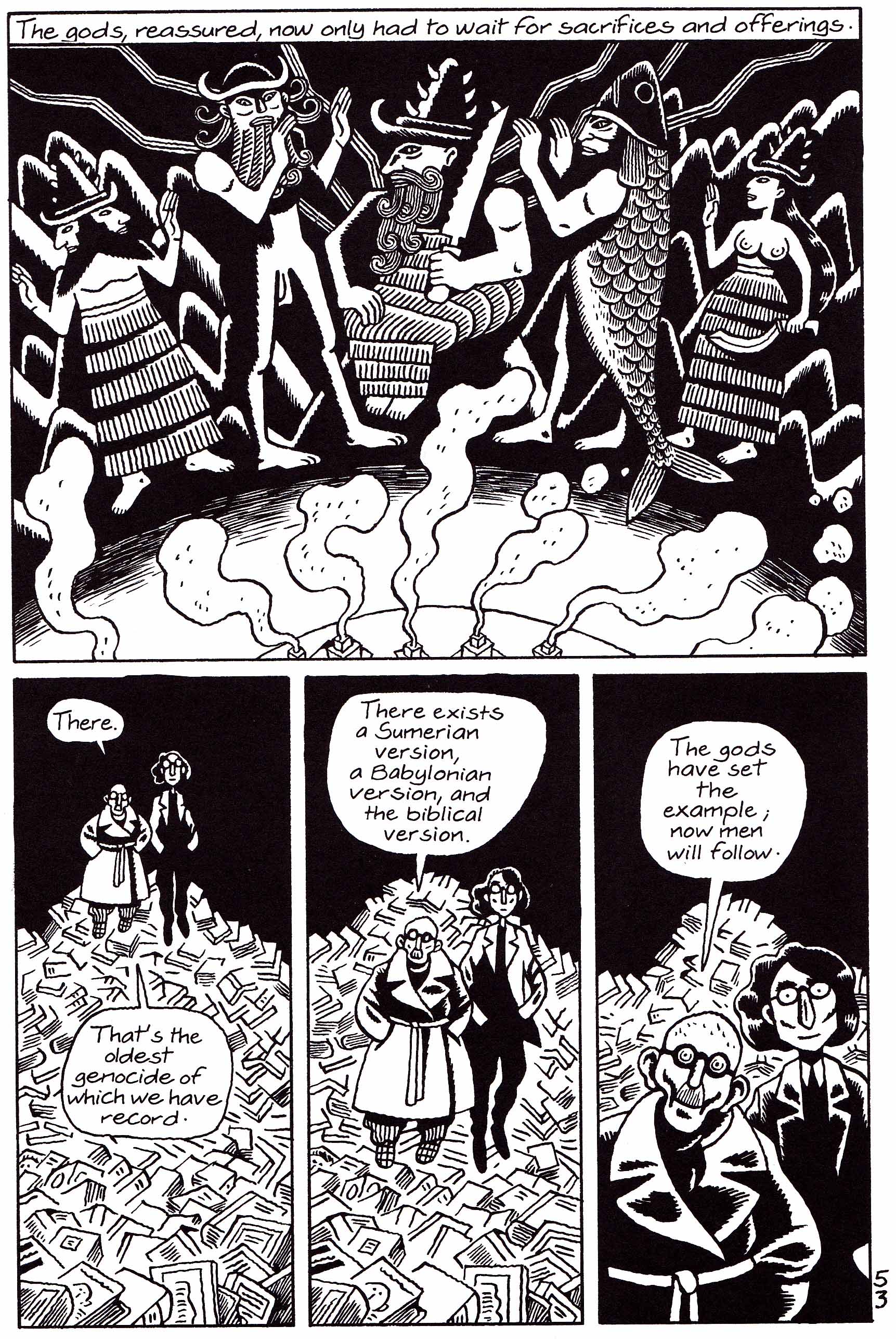

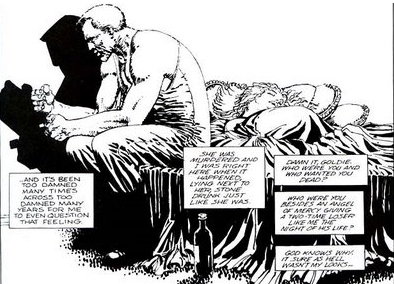

It is perhaps too easy to say that these early comics are a record of their time. They are, of course; they demand that we investigate and reconstruct the discourses of the era that produced them. But to deny the hurtful and derogatory nature of the images in Kelly’s early work, I believe, is also to deny his power as an artist. The images in these early issues of Animal Comics are ugly, but there is something in them that will not be ignored. In his mature work—read, for example, Ten Ever-Lovin’ Blue-Eyed Years with Pogo, or The Pogo Poop Book, or Kelly’s final collection, We Have Met the Enemy and He Is Us—Kelly breaks with these conventions. And the image he leaves behind is this one: P.T. Bridgeport, the circus bear, the character who was, in many ways, the real soul of Pogo, now old, tired, but more real and true as he stares at his beloved swamp and sees not a pristine wilderness but a wasteland of junk. But even here we find a possibility of hope and renewal:

Fig. 7 and Fig. 8: From the last two pages of the title story of Kelly’s We Have Met the Enemy and He Is Us (1972) (pages 41-42)

I started this post with a quotation from Walter Benjamin (translated into English by Harry Zohn) not for you but for me, as a way to remind myself of the value of interrogating images like the one of Pogo and Bumbazine sharing the slice of watermelon. If we fail to recognize images from the past as part of our “own concerns,” Benjamin argues, we run the risk of losing them, and their meaning, entirely. But here again I have left something out. Benjamin adds this final parenthetical statement to his fifth thesis: “(The good tidings which the historian of the past brings with throbbing heart may be lost in a void the very moment he opens his mouth.)”

So, a paradox: we must look carefully, search for these “flashes,” but we also risk negating them and their meaning when we speak or write about them. But to remain in watchful silence offers no real alternative. We must speak of these things, although, as we do so, we are not speaking about the past, not really. We are instead addressing the pain of what it is to live here, now, with each other and with these discourses that continue to blind and disorient us.

Fig. 9: Two gifts.

References

Andrae, Thomas. “Pogo and the American South” in Walt Kelly, Walt Kelly’s Pogo: The Complete Dell Comics Volume 1. Neshannock: Hermes Press, 2014. Print.

Andrae, Thomas and Carsten Laqua. Walt Kelly: The Life and Art of the Creator of Pogo. Neshannock: Hermes Press, 2012. Print.

Benjamin, Walter. Illuminations. Trans. Harry Zohn. New York: Shocken Books, 1968. Print.

Boym, Svetlana. The Future of Nostalgia. New York: Basic Books, 2001. Print.

Curtis, Betsy. “Nibble, a Walt Kelly Mouse” in The Golden Age of Comics. No. 1 (December 1982). 30-70. Print.

Fiore, R. “Sometimes a Watermelon Is Just a Watermelon.” The Comics Journal. April 3, 2014. Web Link.

Jarvis, Eric. “The Comic Strip Pogo and the Issue of Race.” Studies in American Culture. XXI:2 (1998): 85-94. Print.

Kelly, Walt. The Pogo Poop Book. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1966. Print.

Kelly, Walt. Ten Ever-Lovin’ Blue-Eyed Years with Pogo. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1959. Print.

—. “1920’s.” Five Boyhoods. Ed. Martin Levin. New York: Doubleday & Company, Inc., 1962. 79-116. Print.

Pehanick, Andrew. Bridgeport 1900-1960. Charleston: Arcadia Publishing, 2009. Print.

Soper, Kerry D. We Go Pogo: Walt Kelly, Politics, and American Satire. Jackson: UP of Mississippi, 2012. Print.

Thanks to Mary Witkowski and Robert Jefferies at the Bridgeport History Center for their assistance in locating materials included here from the Center’s Walt Kelly clipping file. Also, I talk a little more about the Walt Kelly panel a November’s OSU conference here.