In my last post, Why Is Comics Studies So Predictable, I considered a number of approaches to defining the concept comic, and found them wanting. In particular, I looked at four sorts of approach, which can be summed up (with some simplification) as:

In my last post, Why Is Comics Studies So Predictable, I considered a number of approaches to defining the concept comic, and found them wanting. In particular, I looked at four sorts of approach, which can be summed up (with some simplification) as:

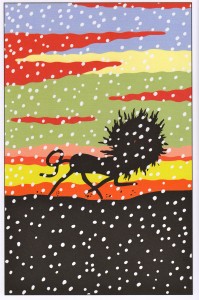

- Formal: Something is a comic if it has the right formal properties.

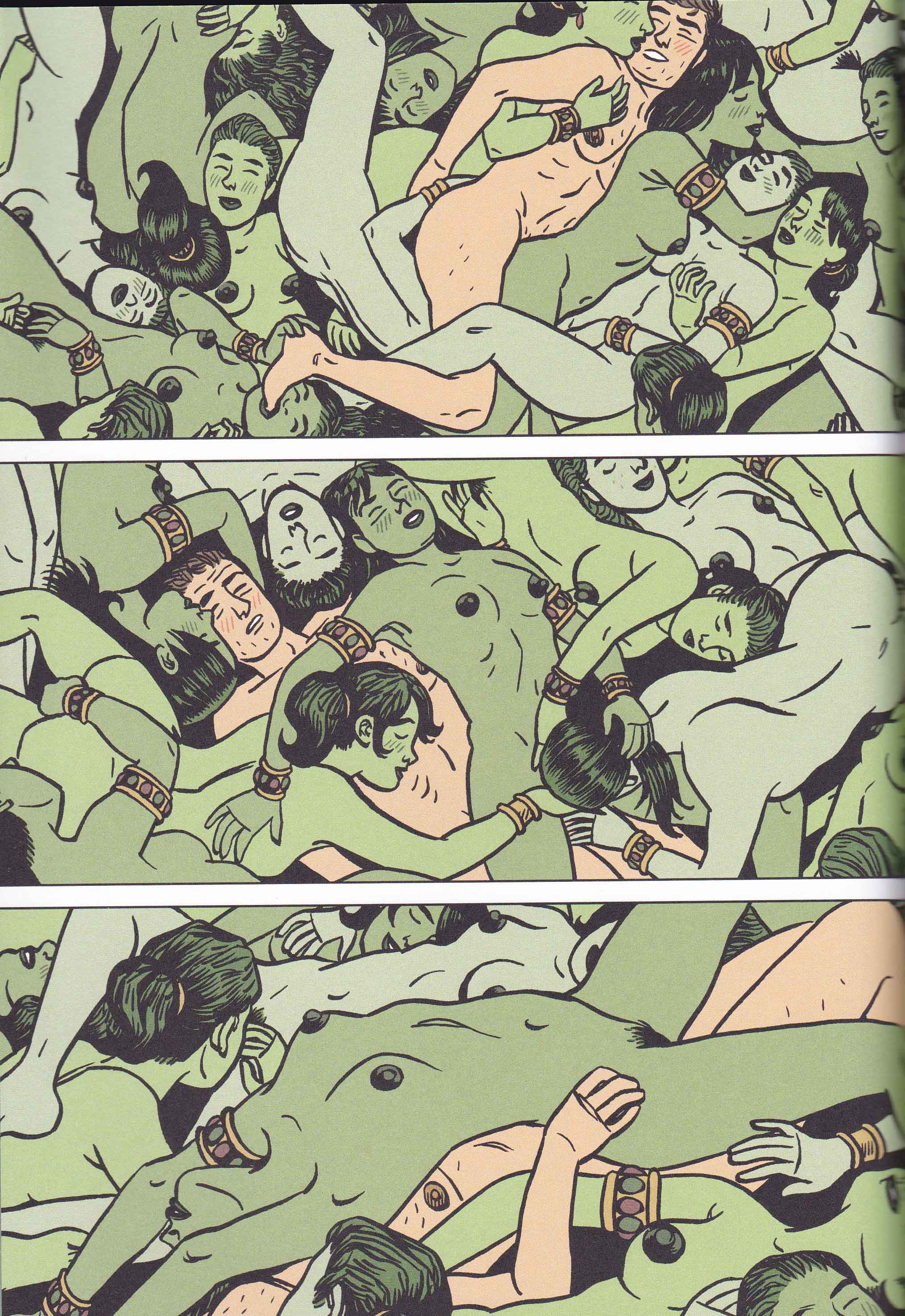

- Moral: Something is a comic if it tells the right sort of story.

- Historical: Something is a comic if it has the right sort of causal or historical pedigree.

- Institutional: Something is a comic if it is accepted as such by the art world.

I also considered approaches (Delany, Wolk, Hatfield) that reject either the possibility, or the usefulness, of a definition in the first place. A predictably lively and helpful conversation ensued – one that ended with Jones, one of the Jones boys, writing this:

…that said, could you at least gesture in the direction of a sketch of a promissory note for what a better strategy for characterizing comics might look like? Do you have anything particular in mind?

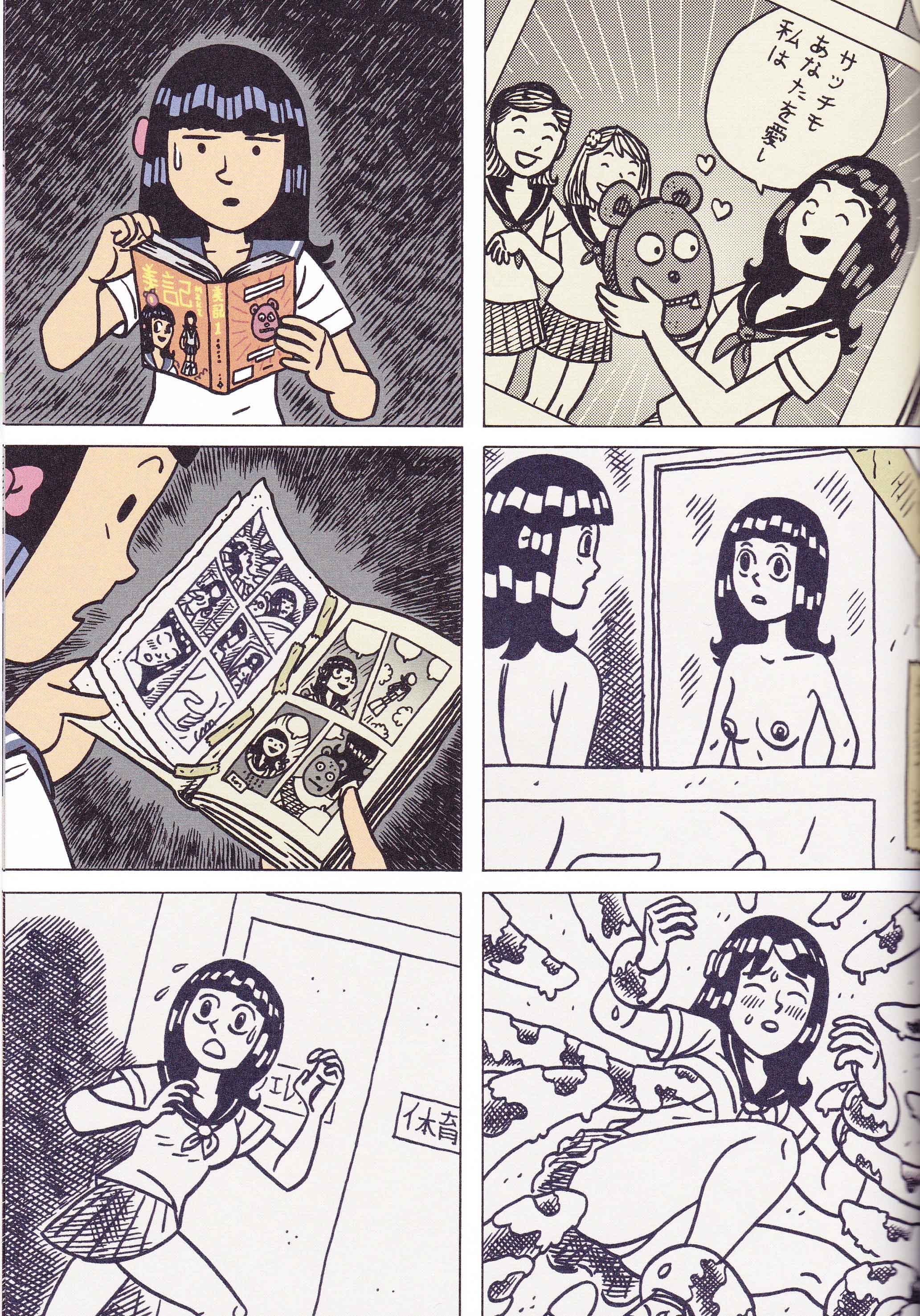

Almost immediately after this, I was visiting the comic studies program at the University of Wisconsin, and Adam Kern (director of the program, comics scholar extraordinaire, and professor of East Asian Languages and Literature) similarly pressed me for a definition, or at least account of the nature of comics.

Now, I should begin by pointing out that I am not convinced that a completely correct, precise set of necessary and sufficient conditions is even possible. But I do think that, even if we had good reasons for thinking such a perfect, precise definition is impossible, it would still be worthwhile to think about initially promising-looking definitions. Why? Because we are likely to learn a lot about the nature of comics, and how comics work, by carefully determining why carefully formulated, plausible-looking definitions fail. For example, discussion of the anachronistic objects that get characterized (incorrectly) as comics by McCloud’s formal definition of comics, such as the Bayeaux tapestry and ancient Egyptian carvings, helped to foreground the important role that institutions and history have in grounding our judgements that particular objects are or are not comics (even if later historical or historical attempts at definition failed equally spectacularly, in part due to ignoring the formal aspects of comics).

So, I began to think about how I would define comics, if I had to give a definition. What is the best such definition I can think of? This is what I came up with, in its initial short, snappy form:

Comics are narratives that we look at, and do so at our own pace.

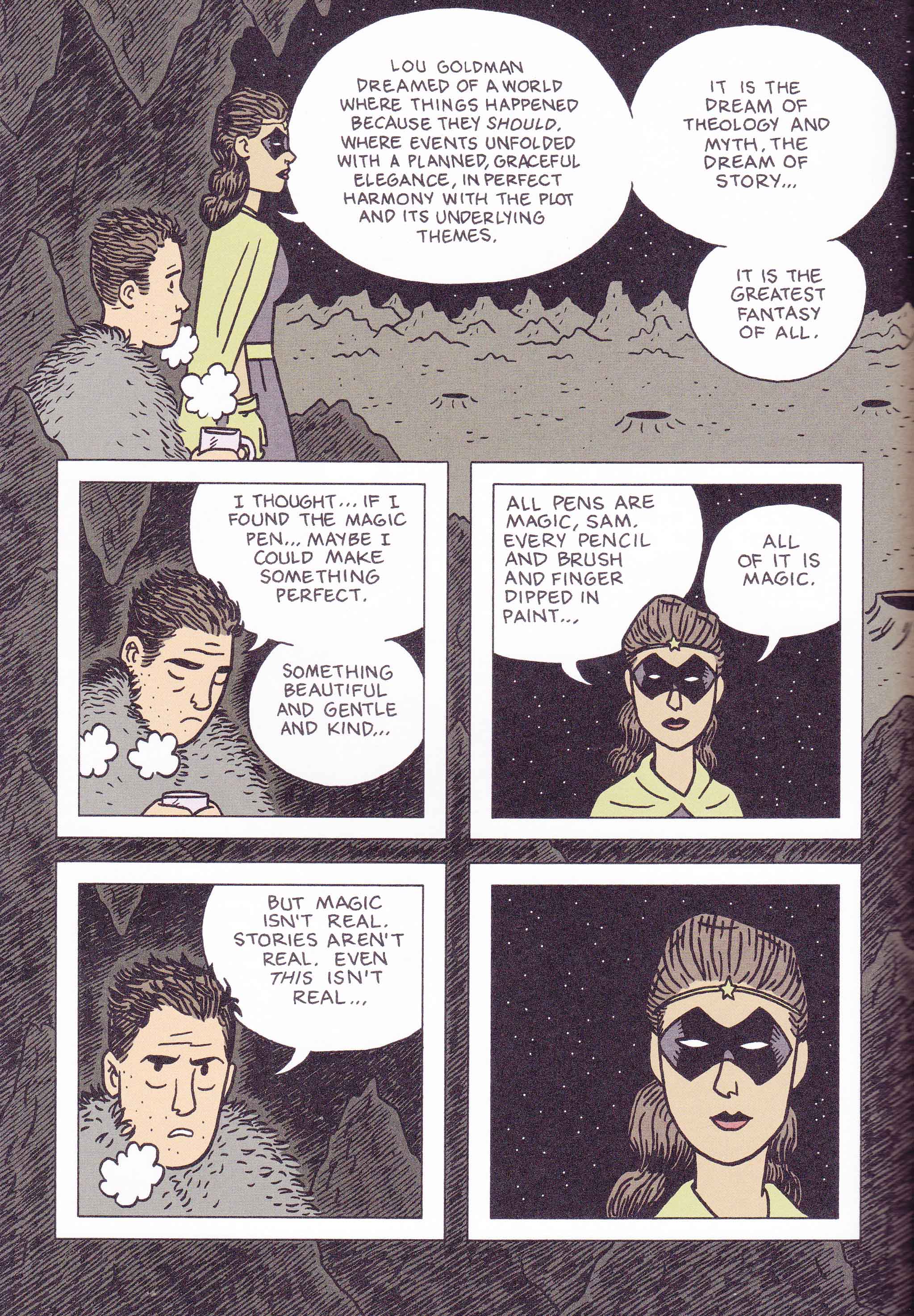

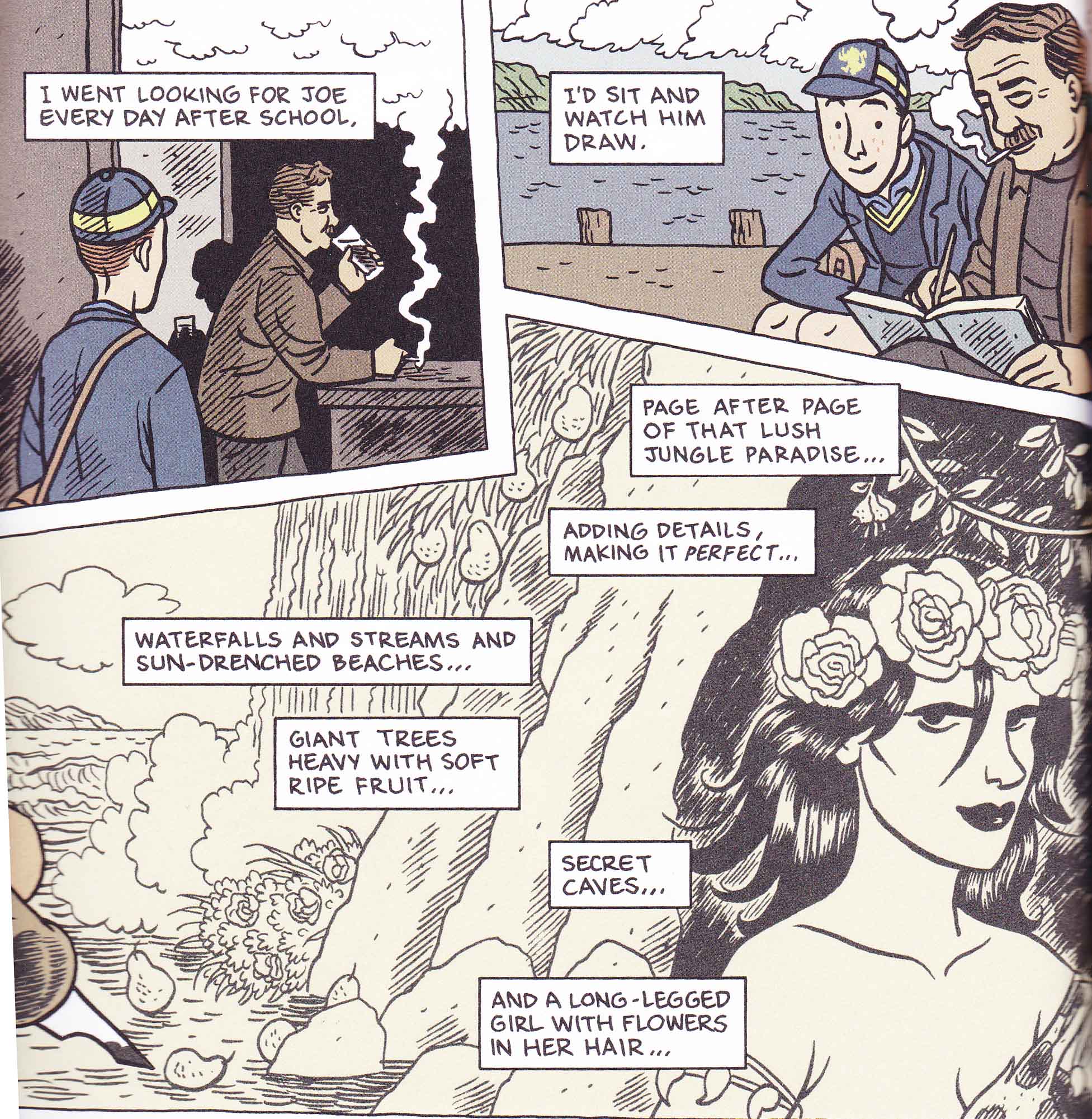

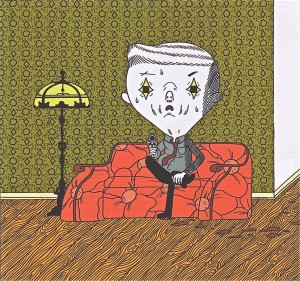

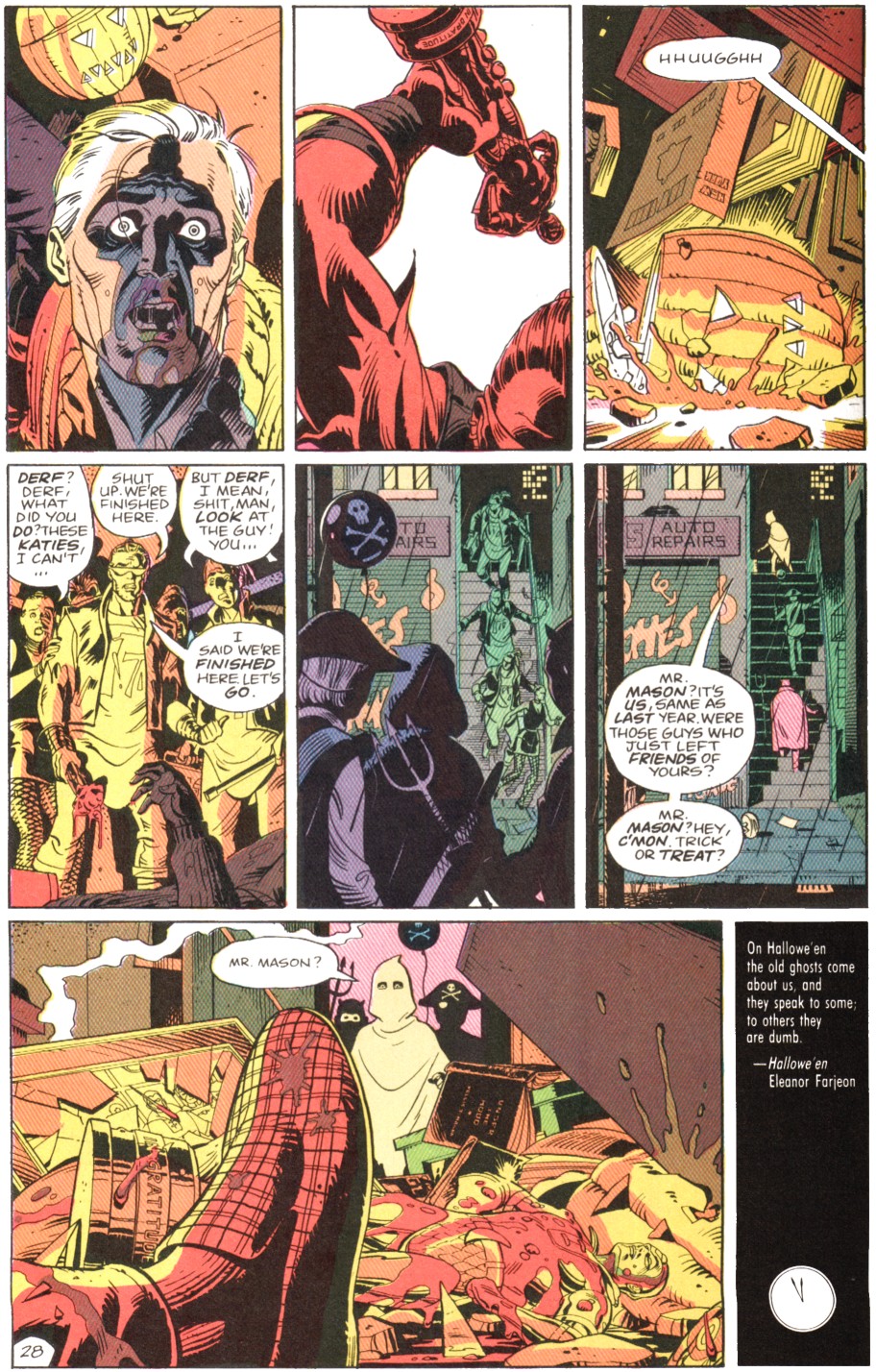

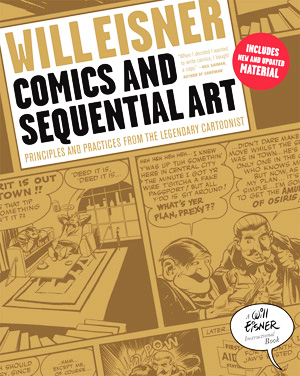

The basic idea meant to be captured here is one that can be traced back to Will Eisner when he writes that, in comics, “Text reads as image!”(Comics and Sequential Art, 1985). In more detail, the thought is this: typically, we experience text and pictorial images differently – we read text, but we look at images. In comics, however, even if we read some parts of the work (such as the squiggles typically found in thought balloons), we look at all of the parts. This is Eisner’s insight: we look at the text in comics in the same way that we look at a painting, which is not the same way that we experience text in, say, standard novels (where the visual characteristics of the font used typically doesn’t matter so long as it isn’t strange enough to detract from our experience of reading). The final bit about looking at our own pace is to distinguish comics from animation, where the pace of experience (of looking) is controlled by the author and/or projector (and this also emphasized what I take to be a critical difference between comics and animation – it’s not so much the movement, but the fact that the viewer doesn’t control the pace of the movement).

There are, of course, some additional kinks to work out. The first has to do with the fact that we can look at anything, in the relevant sense of “look at”. I can look, and admire the visual characteristics, of the font in which this post is typeset. That doesn’t mean that this post is a comic (even if we grant that this post is a narrative in the relevant sense). So it must be the case that comics are narratives that we are meant to look at. But even this is a bit ambiguous – meant to by whom? Here I am just going to bite the bullet and invoke authorial intention in a manner I am comfortable with, but other “Death-of-the-author” types might not be.

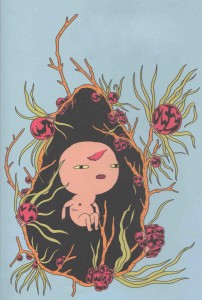

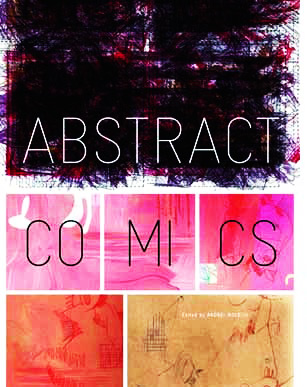

Second, the above simple version implies that any comic involves a coherent narrative of some sort. Andre Molotiu, editor of the amazing Abstract Comics volume, would be very displeased! So I am going to insert some academic-sounding gobbledygook about some kind of “meaningful agglomeration” to cover this case.

Second, the above simple version implies that any comic involves a coherent narrative of some sort. Andre Molotiu, editor of the amazing Abstract Comics volume, would be very displeased! So I am going to insert some academic-sounding gobbledygook about some kind of “meaningful agglomeration” to cover this case.

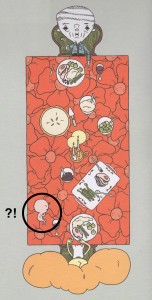

Finally, we need to make sure that everyday paintings and photographs don’t count as comics. So we will invoke a formal constraint – one that doesn’t invalidate the idea that the practice of “looking at” is what is of central importance. A comic has to involve two or more distinct parts that we look at separately. Importantly, however, these parts could be (1) an image and (2) a caption below it, or (1) an image and (2) a speech balloon laid over it, or (1) an image and (2) another image, etc. Basically, it need not be a sequence of two images, but must be a fusion of two distinct visual foci of some sort.

Hence, we arrive at something like this: A work is a comic if and only if:

- It is a narrative (or other meaningful agglomeration) composed of two or more visually distinct parts.

- Each of the parts is intended by the author to be looked at (i.e. experienced, interpreted, and evaluated in the way we experience, interpret, and evaluate images, rather than text), and looked at separately from the other parts.

- The audience is able to control the pace at which they look at each of the parts.

So that’s what makes something a comic.