To continue my February 13, 2014 musings on time, I’d like now to focus on one particular type of perceived time: the subjective experience of the stroller, the old literary archetype of the flâneur.

We can situate this exploration in the larger domain of subjective time experience, and I am still using the crutch of “Duration in Comics,” Sébastien Conard and Tom Lambeens’ fine exploration of Henri Bergson’s notion of durée as it can be applied to narrative comics such as Kevin Huizinga’s Ganges and Chris Ware’s Jimmy Corrigan: Smartest Kid on Earth, as well as abstract comics, including Ibn al Rabin’s Drame de la non-communicabilité chez les phylactères [A Drama of Inability to Communicate among Speech Balloons] and Lewis Trondheim’s Bleu [Blue]. (European Comic Art 5:2, Winter 2012: 92-113). The reason I write “crutch” is that their article convinced me that there was sufficient cause for me to return to Henri Bergson’s thought in the original, and so I planned to engage in the usual literary scholar feint: hastily peruse relevant works over a weekend, select meaningful quotes, tear them out of context, insert into own train of thought, ignore larger framework of assertion—only to run into the following subtle shaming:

Me: Philosophy Colleague, do you have Henri Bergson’s works in your office?

Philosophy Colleague: Oh yes! He’s wonderful. Which ones are you interested in?

Me: I need Time and Free Will, just over the weekend. Working on a piece on time.

Philosophy Colleague: (furrowed brow) Just Time and Free Will? Surely, you need Matter and Memory?

Me: Ummm, yeah, I guess I do…. Thanks!

Philosophy Colleague: Have you read his Introduction to Metaphysics?

Me: Errr, no, I haven’t.

Philosophy Colleague: Well, you’ll really want to read that first; it’s a rather necessary introduction to Bergson’s thinking, and quite clear, too.

Me: Ahhh, yes, of course. (thin voice) I’d better borrow that, too. Probably going to need more than a weekend…

Philosophy Colleague: (chortles) Indeed. Keep them as long as you’d like. (Hands me tomes)

Not the first time I’ve perceived this difference between the two Humanities subjects: it seems that literary scholars have a bit in common with the avian family, Corvidae (crows and jays), as well as Ptilinorhynchidae, the Bowerbirds, in that we collect shiny objects torn from their contexts, arranging nifty new collections where, in the case of the bowerbird, tin can tops can sit in aesthetically pleasing juxtaposition to a spray of lilies and a bit of moss.

Philosophers, on the other hand, and to continue the bird analogies, carefully and systematically arrange their environment as the avian family Ploceidae, aka weavers, do: starting an elaborate hanging nest with an outer foundation of pliable fibers, and layering it with leaves, feathers and other soft things that will cushion the nestlings, stay round or tear-shaped, never get blown off the substrate, etc.

Anyway, back to the crutch issue. Philosophy Colleague, initial readings of An Introduction to Metaphysics and a bit of Time and Free Will, and my professional guilt have all convinced me to spend more time with Bergson, and this can’t happen until summer. So, I’ll continue to poach Conard and Lambeens, and you should keep Bergson in the back of your mind as I do so.

“Duration,” they write, paraphrasing Bergson, “is not a fixed representation of perceptible reality but changing reality itself. It is through intuition that we get a sense of duration and leave behind the everyday perception of things.” (96) [Hmmph…Philosophy Colleague was right, dagblast him; Lambeens and Conard are quoting not Time and Free Will here, but An Introduction to Metaphysics!] They mount a credible argument for the recognition of multiple types of time in the reading of a sequence of panels: the time it takes to read, which isn’t exactly the same as linear clock time in that the reader can slow down, speed up, reread, etc.; the number of panels [space] used to suggest time’s passage (which is why both comics critics and the sci-fi community often prefer the term spacetime: e.g. Noah Berlatsky speaking of “time and identity flattened out across space” in his April 13, 2013 Hooded Utilitarian post, “Flatland,” with Domingos Isabelinho adding in the comments section to this post, “I prefer the concept of spacetime….[T]here are images that Gilles Deleuze calls crystal-images in which more than one time continuum coexist as in the Watchmen examples above. Some comics panels are more sequences than frozen moments in time.” [April 15, 2013]).

Spacetime – highlighting the spatial aspects of the fourth dimension—works beautifully for comics, I think, as we are always moving across and around space (within single panels, across a page, splash or spread, non-contiguously across the pages of a comic as Thierry Groensteen and Pascale Lafèvre help us to understand in their theoretical works) to build up a sense of narrative. Narrative is, of course, a conceit of time. Reading time, diegetic (story) time, and perhaps the most fascinating of all: the interweaving of reading time with story time. Lambeens and Conard note that “…when reading, we live time very personally, in a tied bond with [the] main character.” (104) Though they do not cite Roland Barthes in their article, I do think that Conard and Lambeens operate off a similar distinction between readerly and writerly texts as that used by Barthes, where the “writerly” text demands high-level engagement, a kind of completion of the story by the efforts of the reader. Conard and Lambeens assert that it takes a special kind of relationship between comics reader and narrative, one that “keeps us immersed in a diegetic universe by actively letting a specific space-time emerge.” (106)

So, naturally, it would be fruitful to explore this relationship between reader and story in myriad ways; you could, for example, look at the way time slows down if the affective domain is engaged. I am thinking of Michael Johnson’s last Hooded Utilitarian/Pencil Panel Page post on comics that bring one to weep. I would imagine that panels that move us in this way also slow us down, if not to study them more carefully, then certainly to wipe away tears, snurfle, have our own memories/dreams/reflections for a moment…. Why, isn’t “slow down” a major tenet of our instruction to students—if we teach comics—as we alert them to the necessity of working with the comics text on its own terms, treating it as a rich word and image-based work that demands effort from readers?

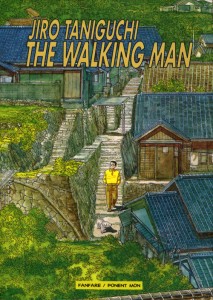

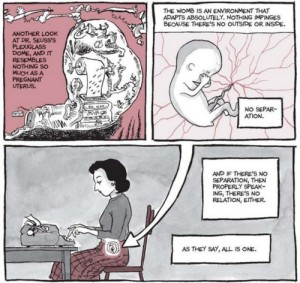

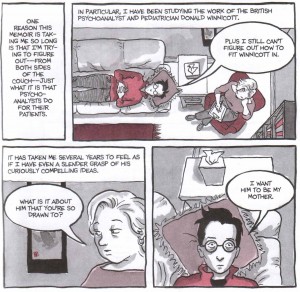

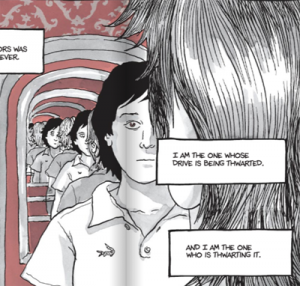

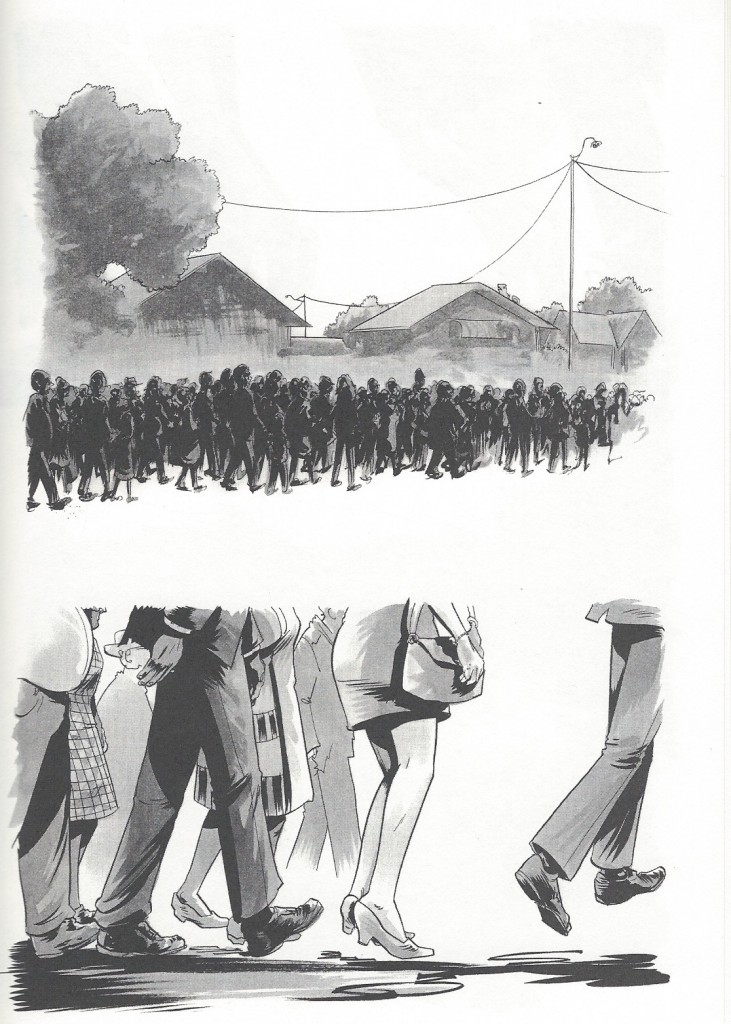

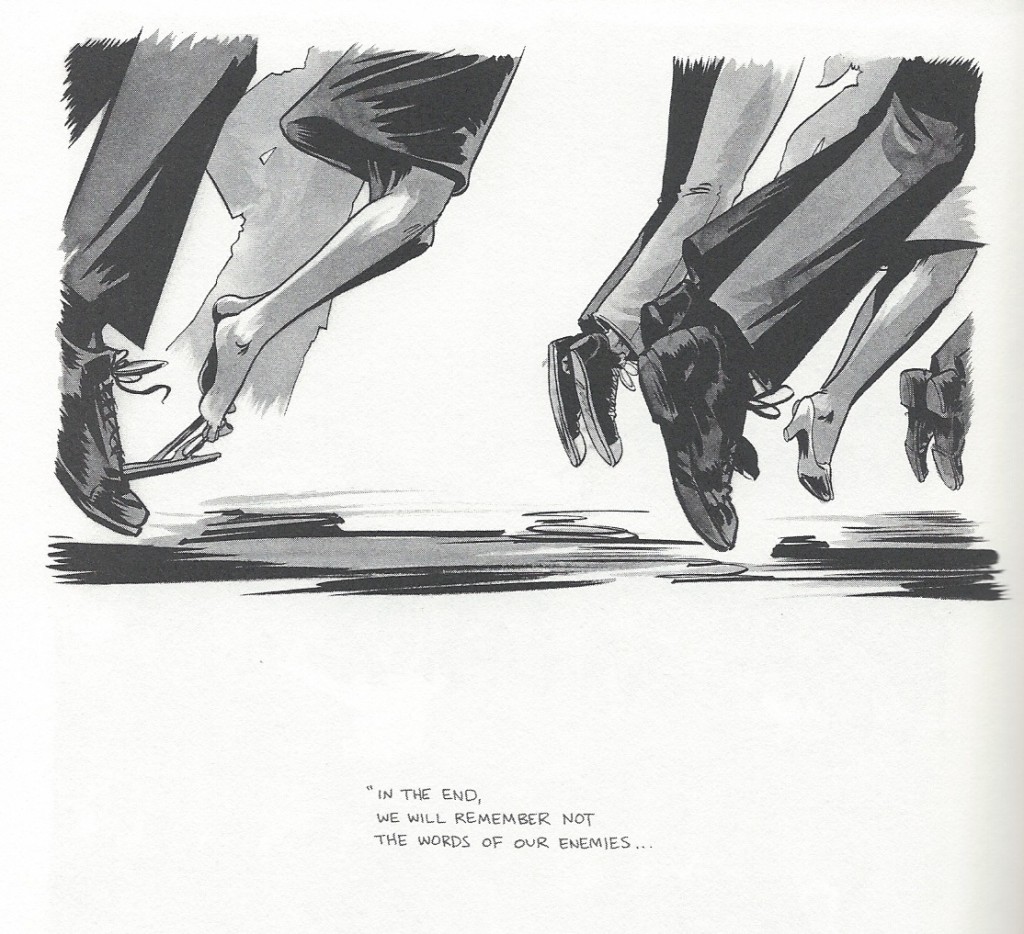

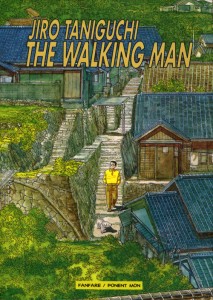

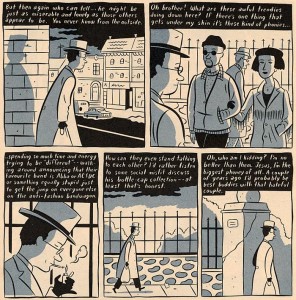

Okay, enough context. So, why do I choose to examine the flâneur in comics? First of all, they are everywhere: Ghost World, Jimmy Corrigan, Palestine, Batman, Little Nemo, Carnet de Voyage, Tintin. Second, their leisurely movement down a street, lane, trail ideally depicts contemplation as it allows the comic artist to break up the slow walk into contiguous panels that move aspect-to-aspect (in McCloud’s words), sometimes following the gaze of the walker, and at other times, allows the artist to overlay the scene with panels that are, or might be, memories of the same place at another time, another place, even an odd, seemingly unrelated connection. The flâneur also becomes the perfect vehicle for sustained internal monologue that can be captured in rather text-heavy balloons (as is sometimes the case in Seth’s It’s a Good Life if You Don’t Weaken) or without them, as in Jiro Taniguchi’s mostly silent The Walking Man.

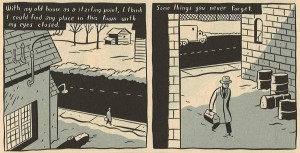

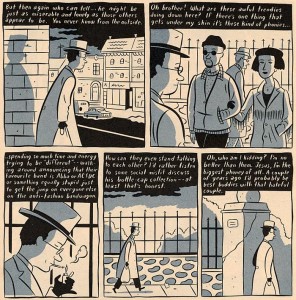

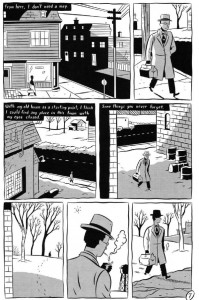

Seth’s and Taniguchi’s flâneurs are not the urbane, hyper-performative types you might find in late 19th century French literature or Djuna Barnes’ Nightwood. They are closer to Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s self-depiction in Reveries of a Solitary Walker and Alfred Kazin’s thoughtful Spaziergänger in A Walker in the City. These strollers animate their thought by walking, as Kant did, as Kierkegaard did; they are within the philosophical tradition of reflective walkers. In It’s a Good Life if you Don’t Weaken, the seemingly autobiographical figure (we’ll call him Seth for convenience) makes his way around the small town of Strathroy in the province of Ontario, Canada, flooded with memories, but also critically observing what is actually around him:

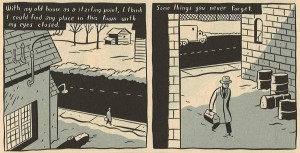

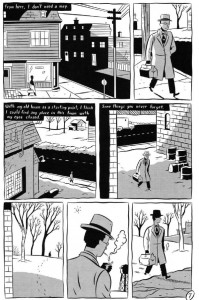

The panels work us around the scene, but also slow us down to look at Seth, engaging in the cigarette lighting process that often occupies the penultimate panels of a page that presents a sequence of mobile thought. Such a set of images calms and quiets the reader (as aspect-to-aspect often does), and puts him/her into the optimum state to reflect along with the protagonist. The duration here is lengthened just so; the number of panels, views, aspects determines—at least in part—the length of time we will devote to the page. Slowed down, unstimulated by overt action, we can enter into the shared subjective time theorized by Conard and Lambeens above, “…liv[ing] time very personally, in a tied bond with [the] main character.” (104) This process works even more effectively when the main character’s thoughts are sketchy, occluded, hinted at, as in this page from Seth:

Though “Some things you never forget” aptly summarizes the preceding panels, it also opens up into a more liminal space in the last three, silent, panels, as we consider both what Seth might also be remembering, and as we, perhaps, start our own sequence of memories, triggered by the non-accidental use of the second person: Some things you never forget.

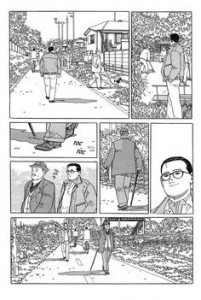

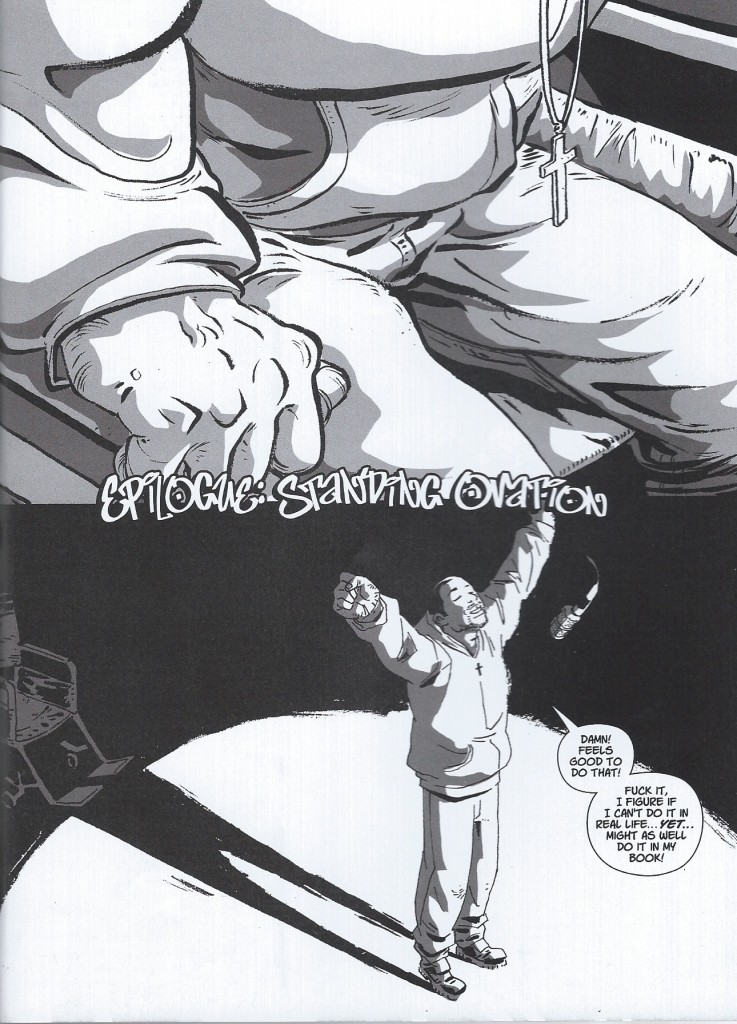

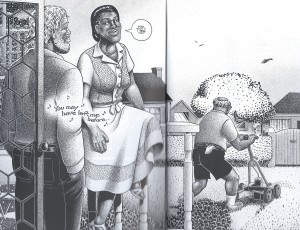

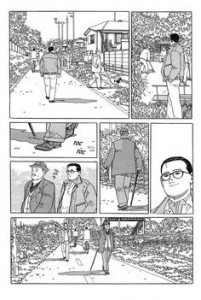

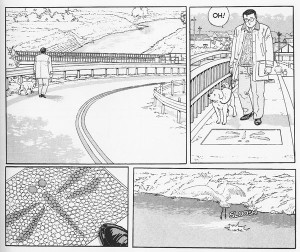

This scene from Jiro Taniguchi’s The Walking Man (just a reading note: though this is a Japanese comic, it is read left to right in the Western manner) may not significantly reveal the walker’s thoughts, but it does present a human-to-human connection that is fleeting, non-verbal, and non-reciprocated:

Watching the protagonist notice, gain on and pass the old man gives us insight into his character (he is interested in those he passes, he notices them), and if the page were parsed further, would probably lend itself to a valuable study of panel-to-panel changes in both diegetic action time (he appears to speed up), and duration.

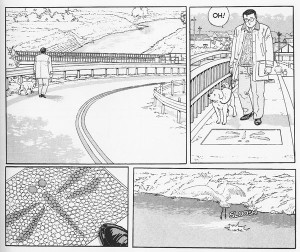

The walker in Taniguchi’s comic is also equally interested in animals, weather, objects: everything he sees, hears and feels (rain figures prominently in a later sequence of panels) appears to bring him pleasure:

As we take this stroll with Taniguchi’s walking man, we see the world with him, learn about his character, walk vicariously, think our own thoughts, experience—maybe—rapprochement with him, and with the world itself. Can you remember other meditative strollers in the comics you know best, or do you have something to say about duration/subjective time more generally?