I actually like superhero comics.

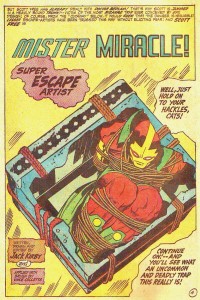

Since it’s a big genre I don’t love all the mainstream capes, obviously, but the idea of them, the inherent trope of extra-powerful characters helping others, is fun and interesting.

There’s something powerful about the mix of whimsy and gravitas in a comic like classic Wonder Woman. Yes, she’s wearing spangled underpants, but she’s jousting on giant kangaroos and swimming deep under the ocean to rescue planes. Anyone who spends a lot of time reading classic myths will recognize this kind of storytelling–there may be helpful woodland creatures flitting around your head, singing their adorable eyes out, but there’s also stepsisters getting their toes sliced off to fit the glass shoe of the prince.

Whimsy and gravitas, the stories we tell our children. Be good, be brave, be honest, be loyal, and you will make the right choice at the crossroads. You will help the little old lady who’s having trouble crossing the stream, and she is the fairy godmother who will save your butt when you get into a bad wood-gathering Ponzi scheme with your idiotic three brothers.

I doubt many people who wander into comics shops or cons feel like Levi-Strauss wandering around the jungle taking photos of penis sheaths and gathering mythos.

But perhaps they should.

For is it not the same? Our cape stories take avatar-figures and set them upon bizarre quests. The Princess in disguise must save the bumbling prince, and when she is back home, she dresses up like a deer to be hunted and ‘eaten’ by her fellow sisters. The wealthy young scion loses his parents before his eyes–set upon a path of vengeance with the loyal family retainer and the local woodland creatures. Certainly, these are not fluffy gray doves, but then, perhaps he is an urban scion. He must battle another winged creature avatar–a bird who cannot fly is bested by a flying mammal who is not a bird.

Right.

So maybe superhero stories are myffic. Fairy stories told in bright crayon colors, yes?

As a kid, I tied a brightly colored towel around my neck and leaped off tall things (occasionally skinning my knee in the process, as one does) and I certainly got some underoos and clothesline and tied my long-suffering stuffed animals to a chair so I could interrogate them with my lasso of truth.

It was fun, and as time passed, as it does, I grew up.

Does that mean that I set those stories aside? In some forms, sure. I became too busy, what with college and then multiple jobs, to catch everything.

But I watched some of the various TV incarnations of the Supes. A friend of mine loved Lois and Clark, and later, Smallville, so I watched them, too. When Buffy came around, I fell hopelessly hard for the young blond high school kid who was a cheerleader by day and a warrior for the light at night. I had a regular Tuesday night dinner with my enthralled friends and we watched, open-mouthed and silent, regular as clockwork.

I saw the movies. X-Men was good, and Spiderman OK, and what the hell was Aerosmith doing writing cheesy dreck like that as a soundtrack for god’s sake? Seriously, Perry, that shit’s beneath you.

Where was I?

Right. I saw the various Batmans, including Michelle Pfeiffer as Catwoman (inspired casting, but maybe not as inspired as Eartha Kitt….). Hellboy. Fantastic Four. Iron Man.

I got into Saiyuki, which is another awesomely classic superhero story. The boys have special weapons, tragic pasts, specific costumes, unique hairstyles. One’s missing an eye! Total classic mythic stuff. Goku even wears a cape!

I read various comics, often shared between friends, in the supe vein. Some I liked, some I didn’t. You can see some of the ones I enjoyed here: Batwoman, Spidey, X-Men, Empowered.

I even did a long and heartfelt Wonder Woman fan comic.

The point is: I read this stuff because I like it.

I like the mix of whimsy and gravitas. I like the juxtaposition of increased power and increased vulnerability. I like wondering what kind of problems a caped crusader runs into. I like seeing Good win over Evil. I like it.

So, for some unknown fucking reason, my various friends and acquaintances kept pushing Alex Ross’s Kingdom Come at me like a drug pusher and a new victim. This is the shit, they’d say. I know you’ll love the art! You have to read this! This is the best art I’ve ever seen, you have to read it!

I demurred.

Finally, one particularly vicious soul bought me the damn thing, or as many issues as were out at the time, and shoved them into my hands.

*

Reader, I hated it.

*

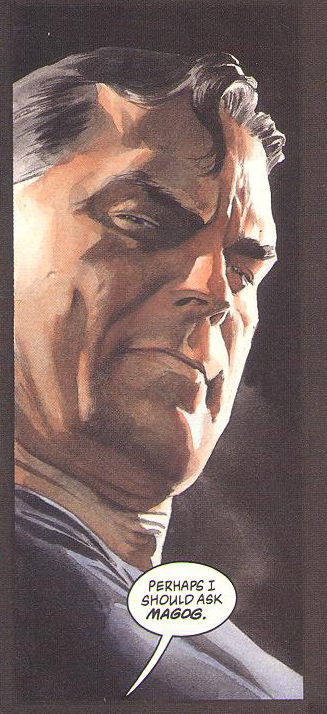

I hated everything about it. The hackneyed plot. The continuity porn. The endless shoutouts to characters I couldn’t remember and wouldn’t have missed if I had. The dumb as shit use of my state as a stand-in for the common people.

But more than anything else, I hated the art.

*

Fucking hated it. Fucking hated everything this art stood for. Hated it with all the passion in my soul.

*

Ahem.

*

Now, someone (probably everyone…) is likely to contradict me here, but I’m going to briefly outline my theory of art and craft. I believe in craft, see. A lot of people don’t. But I do. And since I believe, deeply and passionately, in craft, a lot of people seem to think that I should just luuuuuuuuuuuv that fucking Alex Ross art, because it is ‘realistic’.

But Alex Ross’s art is–well.

Craft. What is craft? Craft is skill, honed with with hard work, talent, and experience, of taking an image (be it a photograph, a live model, a mental imagining) and creating that image in a medium (inks, paper, sculpture, whatever). Composition, line-width, colors, brushstrokes, etc, are all part of craft.

Certainly Alex Ross displays strong craft, of a certain type.

That type is realist copying to the point of dogmatism. Copying, you ask? Copying, I say. For those who do not paint or draw a great deal, the ability to put an image on paper (or canvas, etc) and have it look exactly like a photograph or still life can seem a skill that is difficult to the point of miraculous. It’s not, actually. As an old teacher explained grumpily to us, the surly art class, if you have the hand-eye coordination to sign your name, you too could produce realistic drawings (or paintings).

There are several traditional ways to go about it. You can use ‘Right Hand Side of the Brain’ method. You can use photographs to flatten a scene. You can make a view-finder (popular with the Dutch, back in the day). You can train your mind to see not faces but slight oblong shape to paint with yellow ochre plus titanium white plus burnt sienna one half inch to the left of a center line.

The problem (or gift, for any flaw can be a strength if turned on its side like a knife) with these methods is that they are, at their heart, copying. Is a Xerox machine miraculous? Yes. For skill and craft of reproduction, a Xerox machine is pretty amazing. But it isn’t art. You can make art by xeroxing–shrinking and reducing and enlarging and cutting and pasting and re-reducing and shrinking and enlarging and doing interesting things with various papers or toners. But if art happens, it is because of the human element. The artist chooses what part of an image (or their hand on the scanner, etc) to copy, how to use this amazing tool to create an image that is changed because of the passion and imagination and inner vision of the artist.

If photography is art, it is art because of what the photographer chooses to portray. What composition, what lighting, what cropping, what juxtaposition between subject and scene. Or what scene he had made himself with the help of his models, their costumes, their acting, their stylists.

Craft is the skill, the Xerox machine or camera or brush.

Art is the vision, the imagination, the choice of subject, the human element that steers the machine of Craft down the stream.

It is totally possible to be an amazing artist but have limited craft. That’s like a singer who has a very limited vocal range but makes the most of what she has. Or you could have a ton of craft and not much art. That’s an amazing range, multiple octaves, used to sing crappy Barry Manilow tunes. A waste. (People, of course, can have both art and craft, or, not much of either.)

I’ve seen great art created by kids who were given disposable cameras and taught about composition and lighting. If they choose powerful subjects and use the images to tell a story, even a two dollar Walgreens disposable can turn out some very moving art.

But the same camera in other hands could also churn out (and probably will) a dozen red-eyed blurry dog portraits and another dozen photos of drunk relatives at a birthday party. Not evil, but not exactly a moving artistic triumph we must share with the world at large.

*

So what, you might ask, bewildered by this odd detour into my off-the-cuff art theory, has this to do with one of the most celebrated comics artists?

If the purpose of craft is to portray an artistic vision (in this case a comic story about the importance of superheroes), then we can say art is good when it adds to the story and bad if it takes away from the story.

And by that metric Alex Ross is very, very bad.

*

My friends who pushed Alex Ross on me were in awe of the talent on display in the pages of Kingdom Come. They believed that the art was good because it was ‘so realistic’.

Looking at any given page in Kingdom Come, I can tell that considerable energy was expended to create the images. I could tell, even before reading the end pages of my graphic novel release, that Ross had used props, models, and costumes. To my friends, this was supposed to be impressive.

I guess if you’re not used to seeing the man behind the curtain, it is.

But many fine artists use costumes, photographs, and props.

To me, such preparations are neither laurel wreath nor black mark, it’s just another tool in the artistic arsenal. My favorite artist, Alphonse Mucha, did many preparatory sketches and photographs, often lovely in their own right. Other artists, often working in watercolors or Chinese style inks, use none of that kind of thing.

It has often been said that a true craftsman makes art look effortless.

I don’t know that I would say that, but I would say that a true craftsman makes the viewer see the art and not the effort.

*

So what about Ross? If I like Mucha, then surely I don’t mind realism? If Ross has some skill and craft, what’s the problem?

The problem, dear Reader, is that Ross chooses to remove every bit of whimsy from the mythos of superhero and replaces it with earnestness in the service of a kind of ugly realism that shatters the edges of the created world until heroism crumbles like a balsa wood model in an earthquake.

*

In the classic Wonder Woman stories, there are many ridiculous plots. Is there really an island of women? Do they really joust on giant kangaroos?

Well no, of course not.

In the real world, there are also no sky kangas. (Alas.)

Superheros are pretend.

*

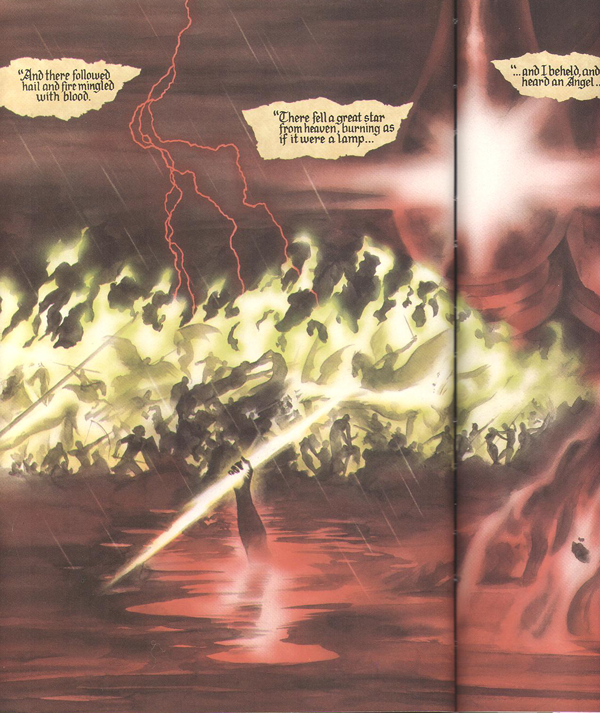

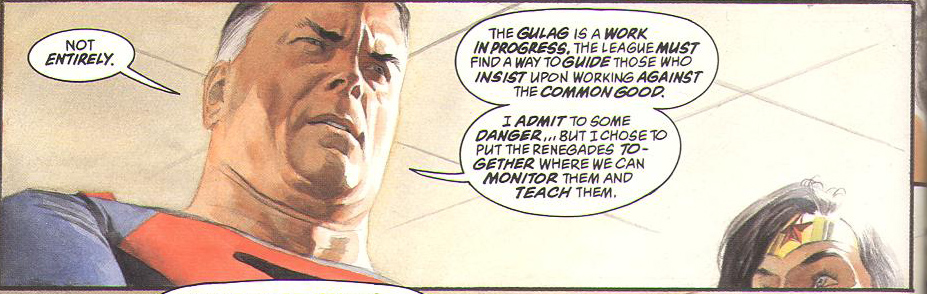

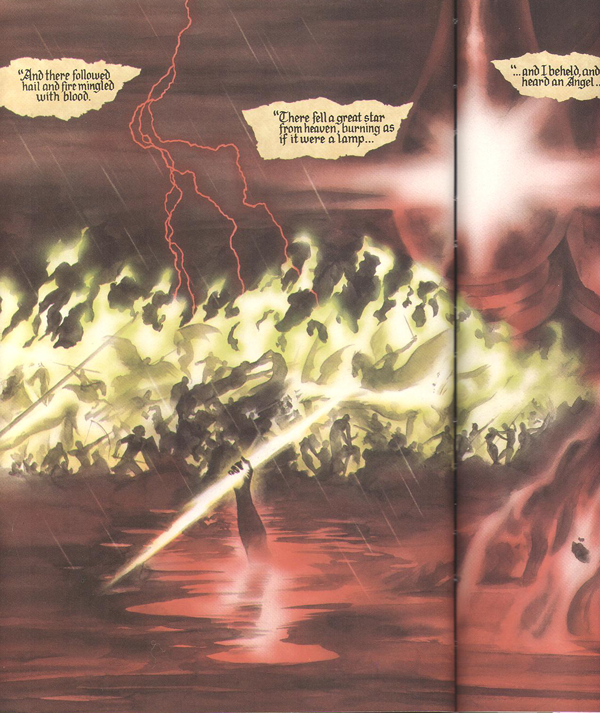

What Alex Ross does in Kingdom Come is take the mythic story of superheroes and paint them hyper-realistically.

The effect is obviously intended to be Serious. Superheros are Needed, because Humanity needs to Battle Evil and the Forces of Good Must Triumph.

Except that by using this hyper-realistic style, by shoving a mythic story, with only slapdash revision and poor grasp of art, into a realistic world, Ross shatters the border of that story, again and again, until the frame cracks and every ugly border of the page is shown, every fourth wall is broken, and the superheros don’t project gravitas, but a kind of secondhand embarrassment so strong that I have to keep the damn comic face down on the table.

*

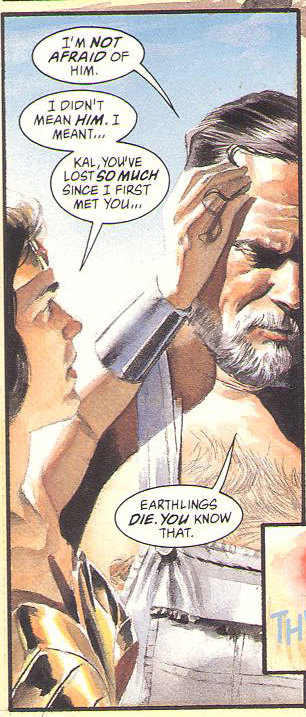

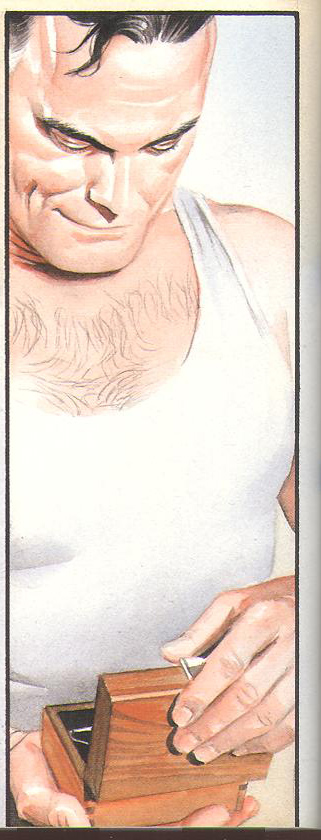

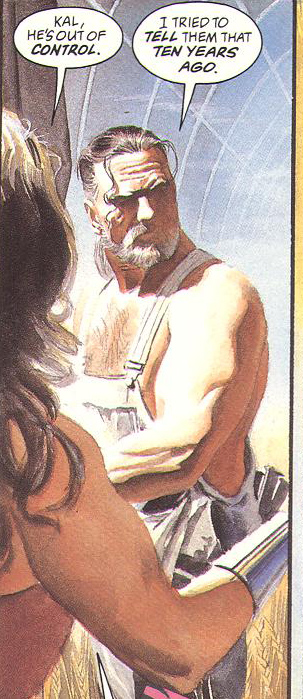

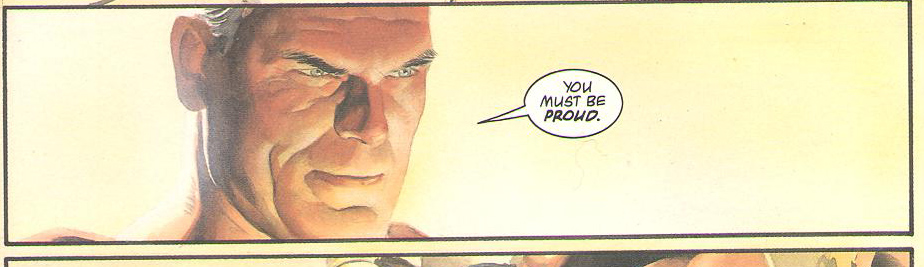

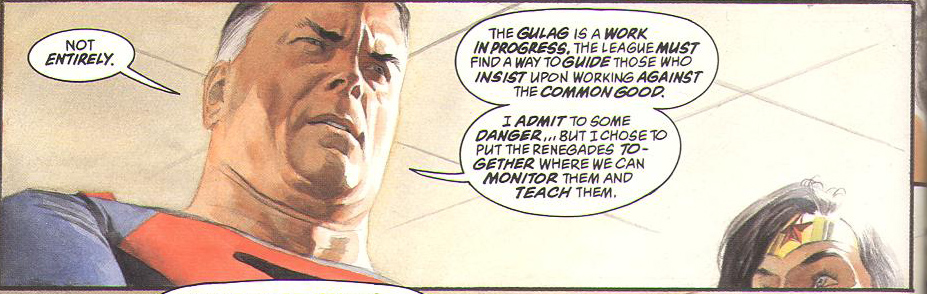

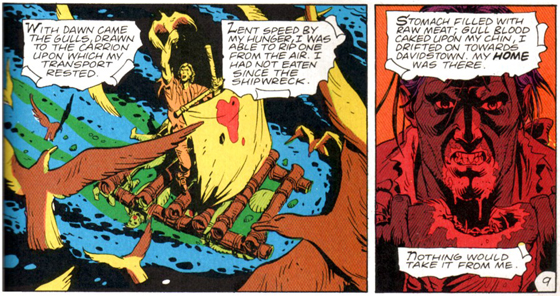

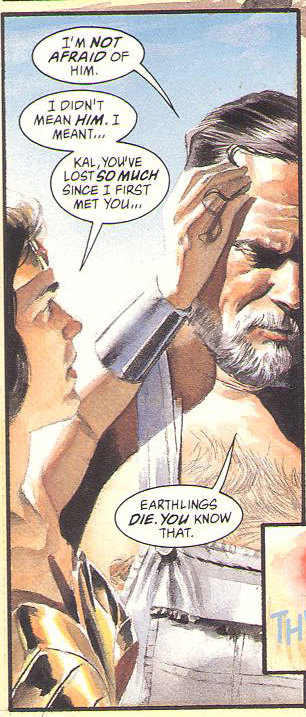

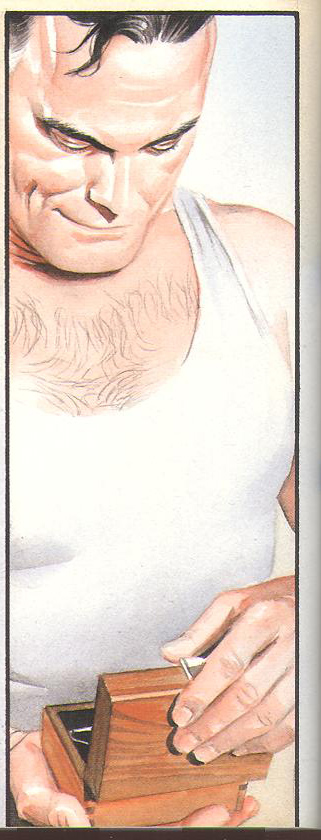

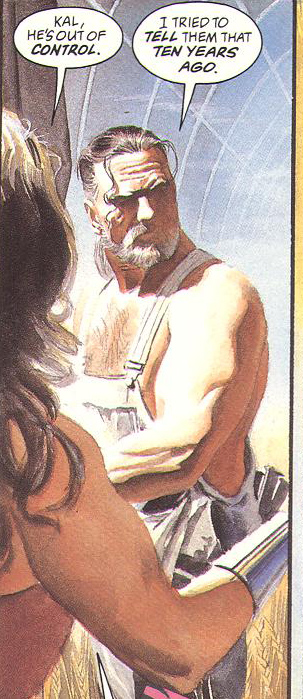

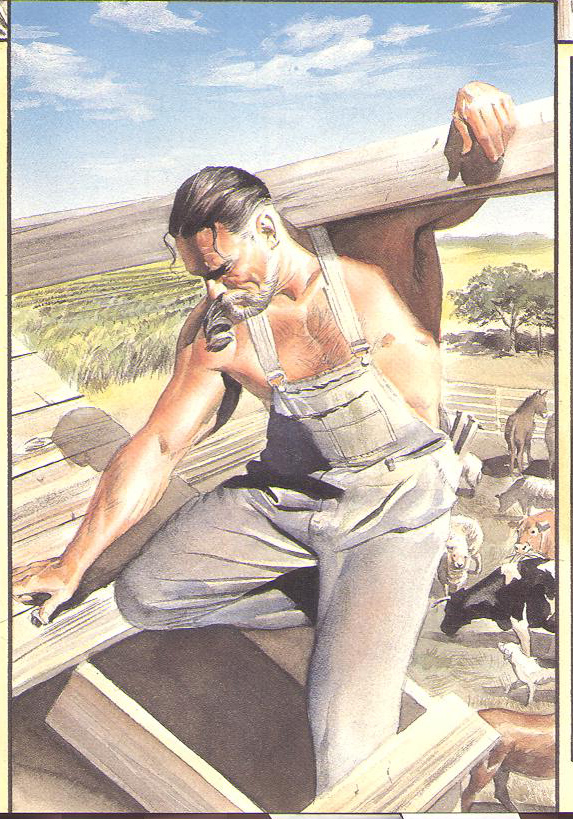

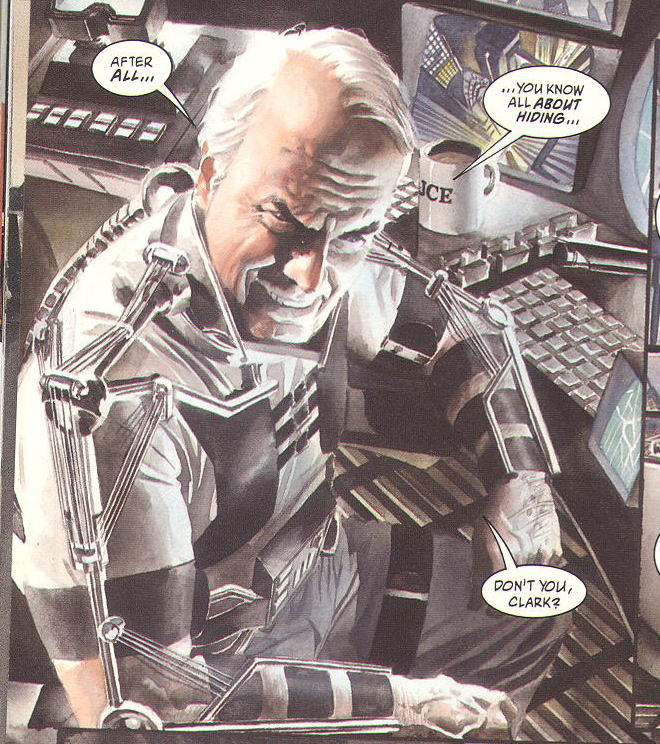

Let’s take a look at Superman, the hero of this tale.

He’s portrayed as an aging, graying, be-chinned older guy. Which, OK, fine.

If Alex Ross has an artistic thesis in this story, it appears to be to prove, once and for all, that The Big Man’s chest hair is gray. Gray, do you hear me? Gray!

All right already.

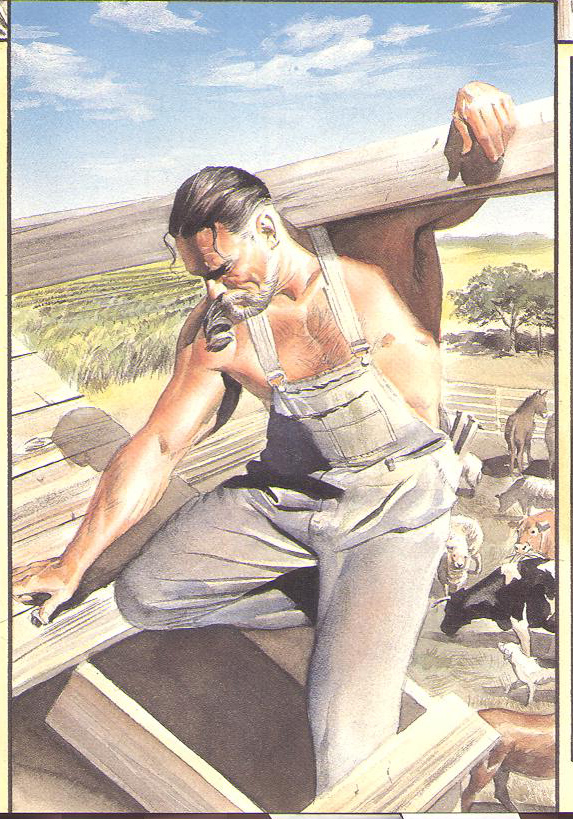

Now I actually wouldn’t mind having a middle-aged superhero, caped or not, portrayed as realistically aging, but what Ross has done here is not portray Superman as a middle-aged farmer, but as, well. Look.

There’s one group of people who over-develop their chest muscles and neglect their legs. They have long hair in ponytails and frankly, more tattoos, but otherwise, Clark is kind of a dead ringer for a guy who’s lived in prison for years.

Farmers and outdoorsmen have built calves and smaller chests, different body types.

The spandex outfits are also a mistake. What self-respecting Kansas farmer would be caught dead in bright red and blue lycra? None, that’s who.

Instead of creating imagery that conjures strength and the tenacity of age or using the crayon-colors to create instant pizazz and focus, or hell, even silliness, Ross’s tromp l’oel conjures unpleasant petty realities.

Anyone who wears polyester underpants that tight during a workout is just asking for a yeast infection. Not to mention the chafing once he starts to sweat. I hope there’s a good portion of CoolMax in that fabric. Did he at least put on some runner’s nipple guards for men? Maybe he’s getting free samples of Body Glide? I hope so, because otherwise, ow.

And what about those red boots? Surely they’re made of rubber. A man that age needs decent arch support especially if he’s active. Fancy wellies with no real soles just seems ill advised. I hope he’s got decent arch inserts.

*

This is the problem with hyper realism that takes itself too seriously.

*

In a normal fantasy story, there are some rules from our real world and then a few extra laws added that, within certain constraints, allow the storyteller to bring us something new and special, something greater than a story that is mired in the muddy reality of the day-to-day.

Tolkien called this a piercing glimpse of joy.

*

If you establish rules in a fantasy world, you have to follow those rules or risk shattering the world. It’s also important, as an artist, to understand and honor the fact that it’s a fantasy. Kangaroos can’t really take Amazons to the outer rings of the galaxy, but, wouldn’t it be cool if they could?

(Answer: Yes!)

*

Kingdom Come tries very hard to portray its fantasy hyper-realistically. The problem is that it obeys only some of the rules and pokes holes in the others, all while taking itself incredibly seriously and obviously expecting its audience to do the same.

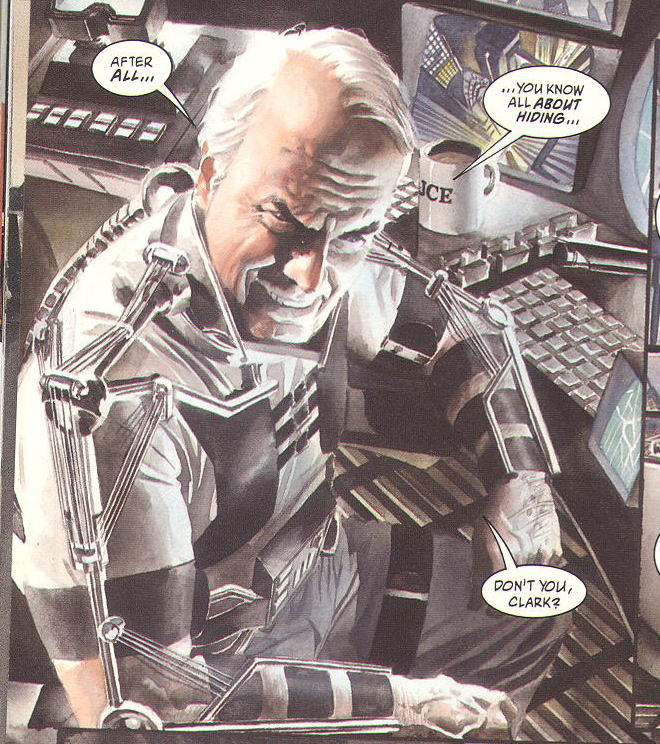

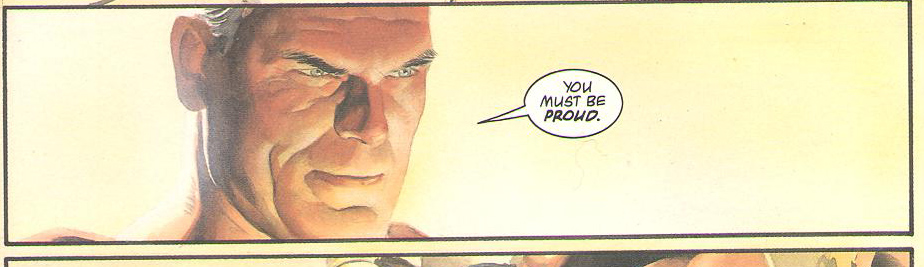

I have mentioned more than once that I’d like to have a broader range of ages and types of characters. An aged superhero could be really cool. But you can’t just age Clark Kent by giving him hyper-realistic chins and then bloat his shoulders like he’s an ex-con. You can’t give Batman a metal exo-skeleton because of old injuries and then expect me to believe he’s got the same bull biceps of Clark Kent. Where’s Bruce’s chronic pain pallor? The weight loss caused by narcotics? The shakes from muscles that fail or from neuropathy-focused meds?

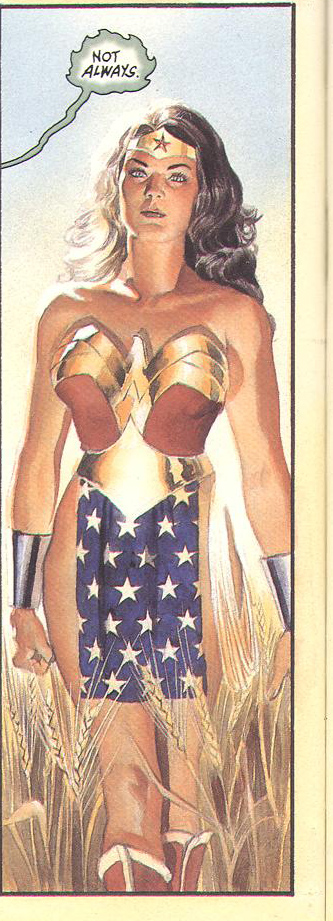

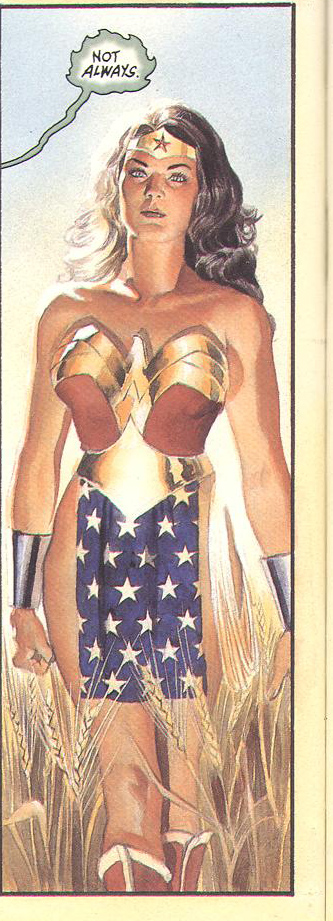

And if everybody else packed on a paunch so that their underoos are tight, why the hell does Diana have a teeny waist as if she’s got on an invisible corset?

Oh, because she’s a reward for the guy with the big red S on his chest, how silly of me to forget. *rolls eyes*

You know what? A woman who’s a warrior would not have a teensy waist. (Nor do most middle aged ladies, but I digress.) Nope. If you look at practicing swordsmen of either gender, such as those who practice kendo, they have a broad belly, not one that is super-sucked in. That’s because they have a low center of gravity.

You can see the same thing in those who practice a lot of yoga. Amateurs tend to think that years of practice will lead to a six pack, but it ain’t so. What it leads to is to a broad deep belly. Why? Diaphragmatic breathing. Breathing into the lungs is nice, sure, but warriors (especially dare I say it Amazons) breathe into the lungs and all the way into the belly. Lots more power.

If you want cheesecake, that’s fine. Nothing wrong with the occasional cheesecake. But don’t pretend it’s real. Don’t expect the cheesecake to add to the feel of reality if you’re mixing sixteen year old photoshopped bellies willy nilly with older-woman bad hair day. Let Diana have a deep belly and and middle aged face and still be cheesecake.

Er, sorry, I got somewhat sidetracked. Where was I? Oh yes. Hyper realism and seriousness and gravitas.

Right.

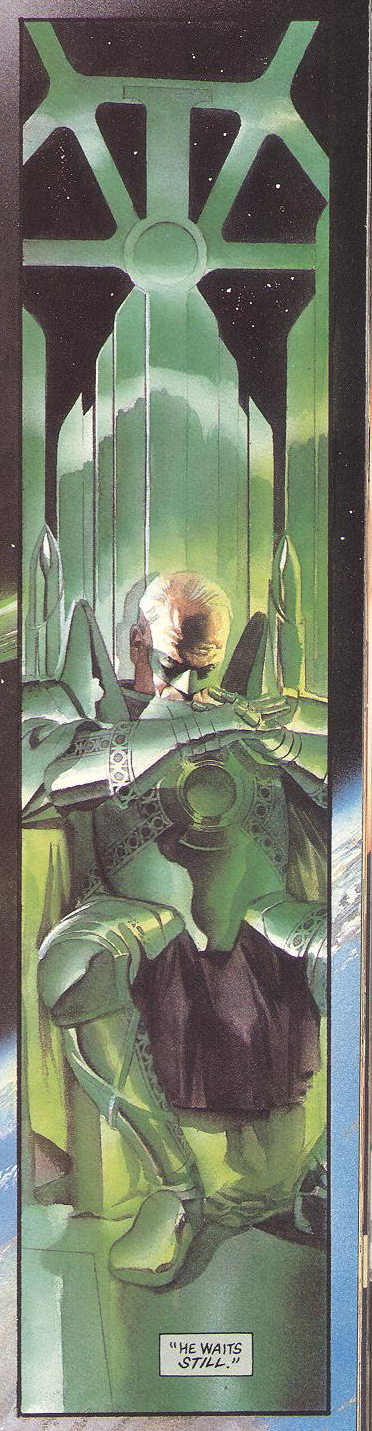

The problem is not the aging of the characters. The problem is the patchy slapdash application of the aging rule. Clark’s got gray hair and a flippy old dude pony tail, but Diana’s got a girlish figure and the same hairstyle she had in the forties? Uh huh. Batman’s managed to invent an exo-skeleton for his broken body, but–

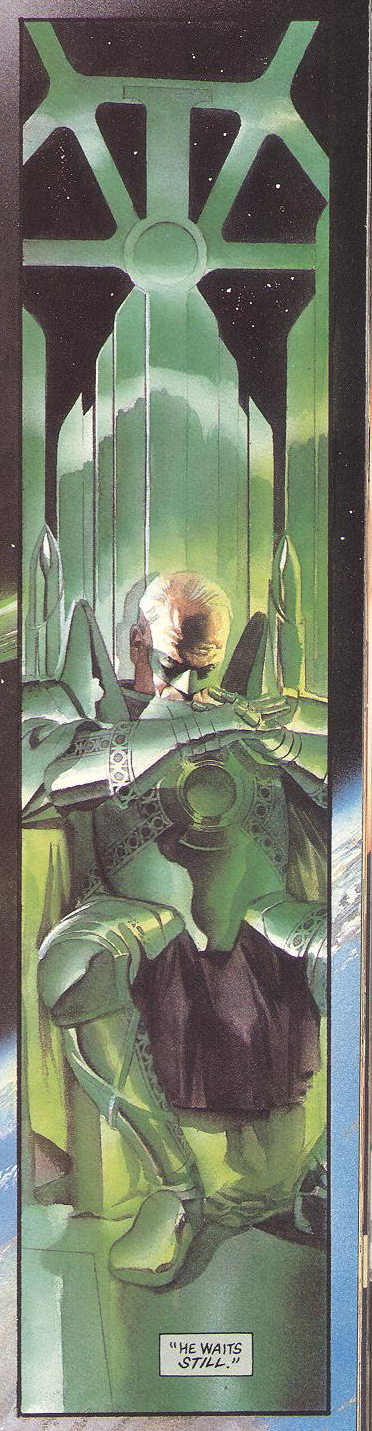

Look, in the real world, young guys wear spandexy football uniforms or whatever, but grown men normally do not wear bowling-ball shaped glowing green armor. Especially with a, what the hell is that anyway? Some kind of black satin loin cloth? Panty apron? I don’t know, but it’s weird. Weird and unattractive.

And loud. Really loud.

It looks strange. Sad.

In more abstract or symbolically painted comics, we’re not obsessively shown the seams of the spandex costumes. We’re not shown the exact way a piece of green armor fits unpleasantly against a human body and then be expected as readers to believe it’s functional as a warrior’s uniform.

If you’ve ever seen a beat cop or an armed member of the military, their bearing changes when they’re wearing their gear. I’m not talking about the shoulders back and head straight (although there is that), I’m talking about the way those heavy belts full of maglight/walkie-talkie/cuffs/gun/stunner/notepad impact the way those people move and stand. Their elbows sweep differently. They don’t bend at the waist in the same way. Their hand will automatically move out to keep a truncheon or tool out of harms way if they turn quickly. You can tell they are aware at each moment of the items they’re carrying, that these items have purpose, that it’s an important and serious uniform built on utility.

People wearing full and immovable body armor do not slump in a chair with their legs spread to reveal their black shiny panty crotch cloth!

They just don’t. It’s not believable. And why glowing green? Yes, someone from continuity porn ville will be sure to point out endlessly why I am wrong wrong wrongity pants, but come on. No self-respecting warrior would wear day glo green bowling ball shaped armor with a black loincloth in this day and age. I mean, lol WHUT. No.

It’s embarrassing.

Which is kind of a problem.

Every time I look at this page, I think, “Put on some pants!”

“Put on some pants” is a strong, visceral reaction but it’s the wrong reaction. For the purpose of the story, I’m supposed to be feeling sadness or worry or fear for the characters and their plight, not slapping my hand over my eyes and thinking this is just like the time I went to an ill-advised Star Trek convention and got hit on by a man three times my age who was wearing some kind outfit made of what appeared to be bits of colored pantyhose, OK?

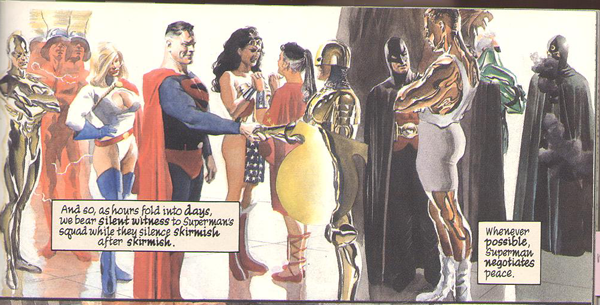

Just about every page has a panel like this. I’ll just get into the story and begin to believe and then a panel will shove the impossibility of this story ever being even remotely true into my face. Again and again and again.

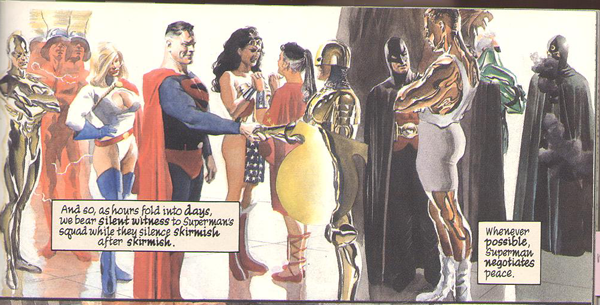

Here we see a kinkster in gold PVC, dial-a-naughty lady in a super girl outfit from Cirilla’s, the big man in underoos, a strange man in armor holding a shield that makes him look pregnant, and their obviously baby-oiled personal trainer in boxing boots.

And you know, that’s fine. It’s not great, it’s not ideal, but–

The whole damn book is also ugly.

For the main theme of the book, Ross chose a complementary color scheme. Since the colors are opposite, they’re jarring. I have no doubt that Ross intended this jarring effect to increase the feeling of conflict.

Only problem?

He chose red and green.

Welcome to Christmas in comic town, boys and girls!

But enough.

The craft, the talent, the skill, does Ross have that? He can make images that have distinct features, sure, but according to Vom’s Theory of Art, he has failed. Failed because each of these effortful, carefully crafted images betrays instead of supports. The tone, the story, the essence, the theme, all of them are subverted instead of supported by the art. I have no worry for the characters on their quest or joy in the characters’ triumph.

I just want them to put on some normal pants.

__________

Click here for the Anniversary Index of Hate.