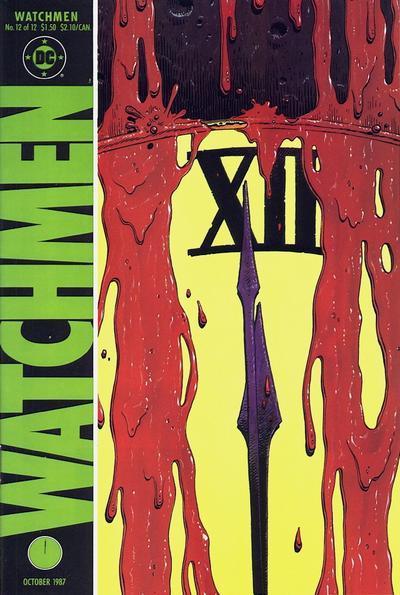

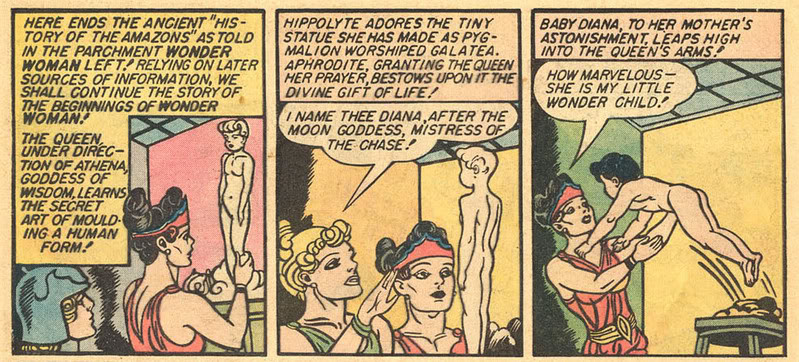

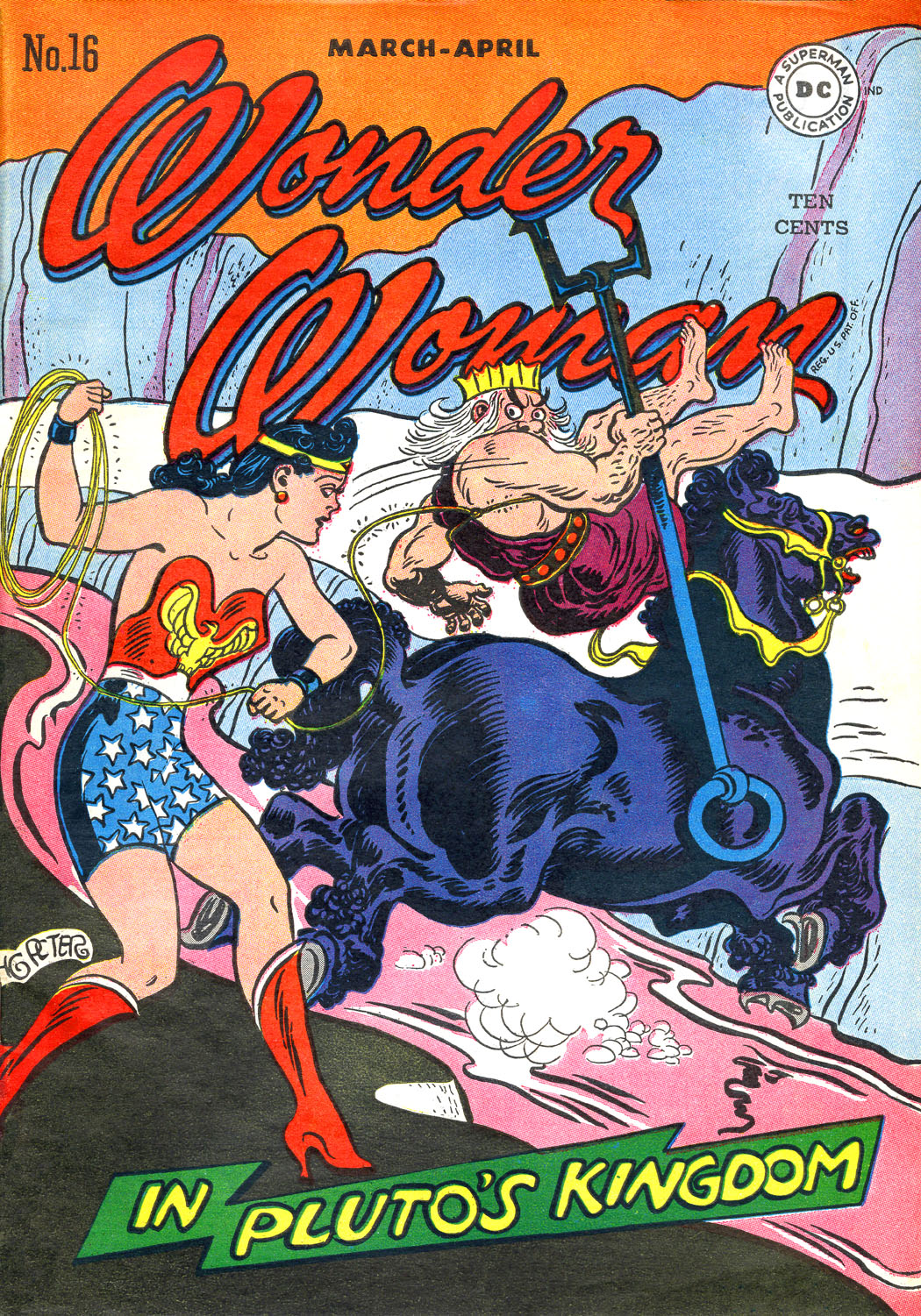

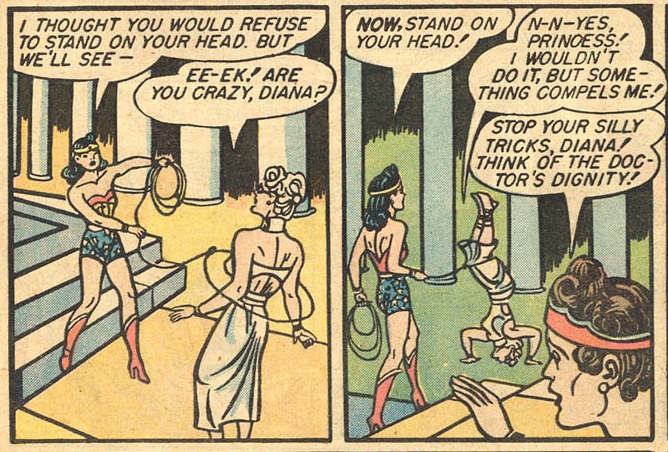

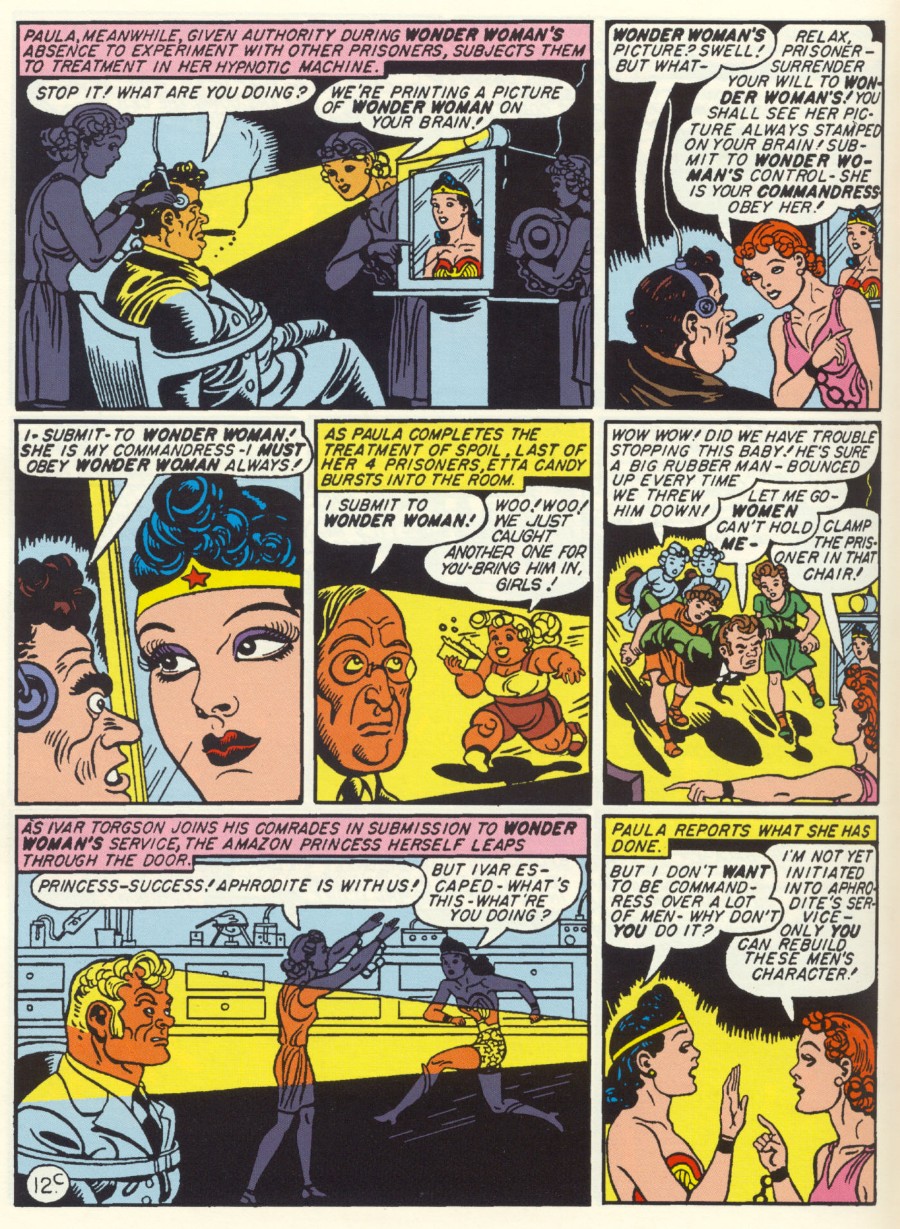

As I’ve said before, my book, Wonder Woman: Bondage and Feminism, came out last week. It’s published in the Comics Culture series at Rutgers University Press. My book is the second volume to be published; the first, released in late 2014, was Andrew Hoberek’s Considering Watchmen: Poetics, Property, Politics, focusing on Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons’ Watchmen.

As I’ve said before, my book, Wonder Woman: Bondage and Feminism, came out last week. It’s published in the Comics Culture series at Rutgers University Press. My book is the second volume to be published; the first, released in late 2014, was Andrew Hoberek’s Considering Watchmen: Poetics, Property, Politics, focusing on Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons’ Watchmen.

Andrew’s book is appreciative but not reverent; he’s especially skeptical of the political stance in Watchmen. HU has talked a lot about Alan Moore’s politics over the years — so I thought it would be interesting to talk to Andrew about his take as the last post in my book release roundtable. Andrew and I spoke by email.

_______

Noah: Your central argument about Watchmen’s politics, as I understand it, is that Watchmen is based in Moore’s sweeping distrust of institutions. For Moore, that connects to 60s anarchism and progressivisim, but your point is that it’s also the basis for the neoliberal attack on government institutions. So when Moore rejects political collective action, he ends up on the side of Reagan and Thatcher, who he hates. Have I got the argument right there? And maybe you could talk a bit about where or how you see Moore rejecting collective politics?

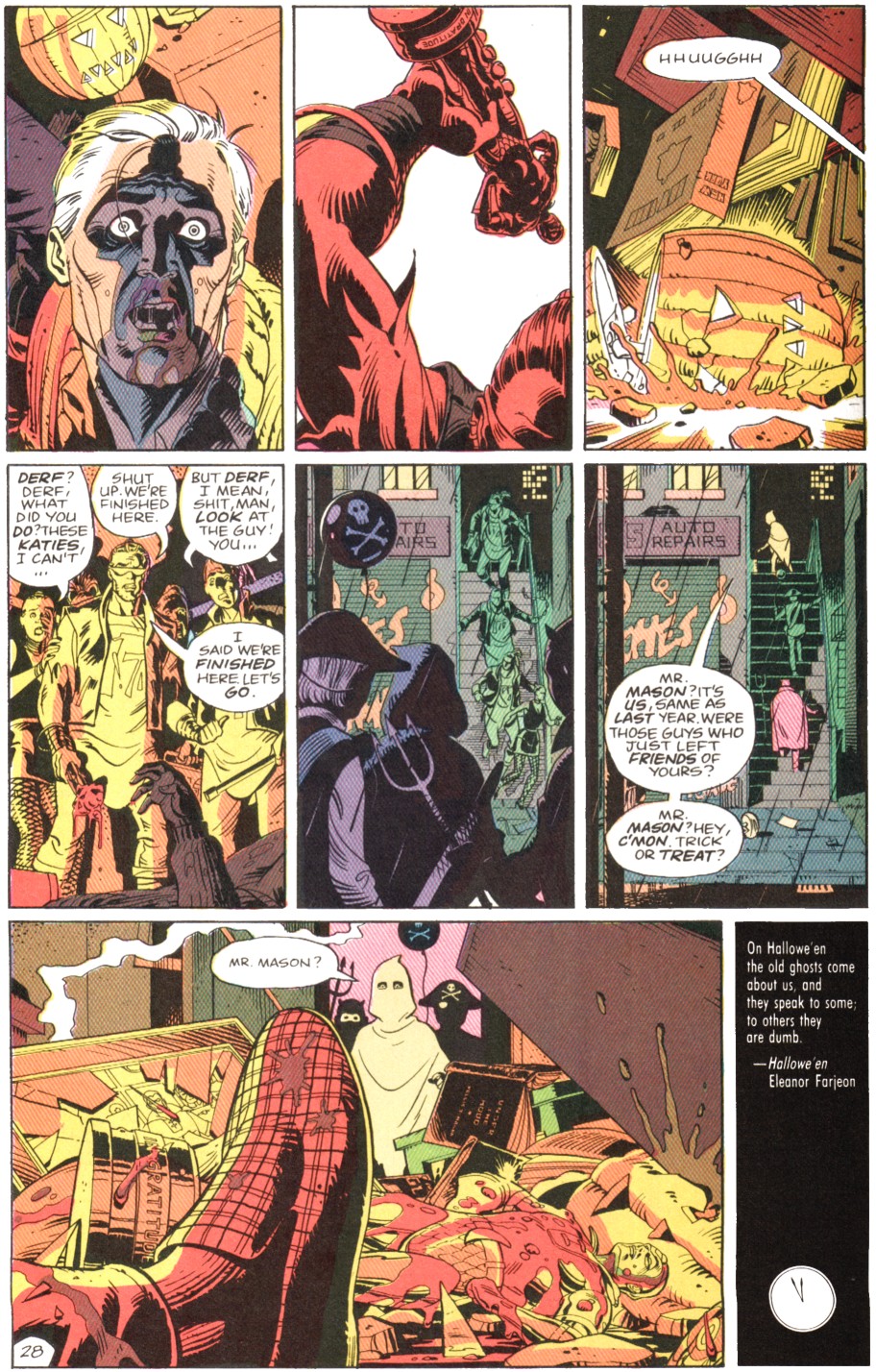

Andrew: I think one example, perhaps relevant now, is the protest against Nite-Owl and Silk Spectre freeing Rorschach from prison that spills over into a group of skinheads killing the original Nite-Owl, whom they confuse with Dan Dreiberg.

Another way to think about it is the fact that Moore’s respect for individualism transcends actual political stances, to the extent that the rightwing Rorschach is a much more sympathetic character than the liberal Ozymandias. Ozymandias is a classic totalitarian figure, someone who (like Stalin) wants to impose plans from the top down and who doesn’t care if literally millions of people have to die in the process. This is very much the kind of figure that Reagan or Thatcher deployed to justify both their foreign policy and their domestic cuts, and that we still have with us in the form of the (absurd) assertions that Barack Obama is a socialist.

That said, I think “ends up on the side of Reagan and Thatcher is strong.” It’s probably more correct to say that he shares an anti-collective stance that hadn’t yet become totally the property of the neoliberal right at that point (It was still central to the sixties left from the Port Huron Statement to the anti-Vietnam movement), but was on its way to doing so.

Noah: So, do you think it’s possible to see Ozymandias as in some ways a critique of neoliberalism, or as trying to think through the connections between liberalism, capitalism, and authoritarianism? You say that Veidt is a classic totalitarian figure, but he’s awfully pro capitalism. And it’s not industrial Nazi-era capitalism either; it’s way more late capitalism, consumerism of the image, it seems like (part of his evil plot is essentially to make a movie.) Casting Veidt as the villain seems like it’s at least in part casting big business as the villain.

Andrew: That’s a good qualification. As I was writing the book I had my eye on the way that Veidt’s portrayal exemplifies a general distrust of institutions that has gone from being a shared feature of both the left and the right in the cold war period to a hallmark of neoliberalism. But another way to think of Veidt is as a figure who embodies Moore’s distrust of large-scale capitalism–a thing I associate in the book with the way he stands for the big comic book companies who exploit the intellectual property of work-for-hire creators. At the same time, it’s when Ozymandias steps outside the profit motive, and attempts to perform what he believes is an altruistic act, that he becomes the villain of the piece. Moore’s thinking about the comic book industry and his general politics remain entwined here, in that the celebration of individual comic book creators remains entwined with a kind of romantic ideology of small property ownership (in this case intellectual property) that’s long been central to American thought, and in some ways has facilitated or served as cover for the rise of neoliberalism. We think of Reagan and his successors as champions of small business–in part because they continuously tell us so–but their policies have largely benefited big capital.

Noah: Veidt’s capitalism doesn’t end though. And in fact he takes advantage of his knowledge of the change in the world situation to switch his investments around and make even more money. Liberal one-worldism and neoliberal corporation seem to fit together seamlessly.

I guess I wonder in part whether the critique of institutions you point to, or the sympathy for Rorschach and the distrust of Veidt — the assumption in your book seems to be that that’s politically retrograde or problematic. But— I mean, for myself at least…if the book is anti-Stalinist, and anti-violent revolution, which I think it is, I’m kind of on board with that. I feel like Moore points out that revolutions are really bloody, kill real people, and don’t necessarily actually change all that much, or can’t be counted on for real transformation. Those all seem like reasonable points — and stand in contrast to V for Vendetta, for example, where V seems infallible and revolutionary violence and torture result in Evey’s personal transformation rather than in the kind of pointless pile of corpses you see in Watchmen.

It also seems prescient in terms of our current political moment. Obama’s not Stalin, obviously, but like most of our Presidents he’s happy dropping bombs on people in the name of a better world. He really doesn’t look all that different from Veidt in a lot of ways (he’s even a successful creator of intellectual aesthetic content, right?)

Andrew: The Obama-Veidt comparison is a fascinating one, although I guess an even better comparison would be Veidt and Mitt Romney, since Romney too made a lot of money and now seeks to turn his attention to public service. (Of course he didn’t make it all on his own after starting from the bottom, the way Veidt and Drake did.) For my money, though, I think the things that are problematic about Obama actually have to do with his very Reaganesque dislike of large organization. For all the flak that he takes for his past as a “community organizer,” this is a figure whose commitment to ground up consensus building reflects a sixties left critique of big government in an era when anti-government sentiment has become a major tool of those in power. Obama’s missteps (including, one imagines, those with the security state, although we’ll probably never know the details there) seem to me to be a property of his desire to compromise and build consensus with everyone. To my mind I’d prefer a Lyndon Johnson who knows how to work within organizations and who isn’t afraid to strong arm opponents to get what he wants. I actually think Lyndon Johnson is–mistakes with Vietnam aside–an unacknowledged hero of the twentieth century. I’m getting a bit away from Watchmen here, but these days you don’t see too many celebrations of institutions on either side of the political fence: Spielberg’s Lincoln is one of the few I can think of, and a great, unheralded film for that fact.

Noah: Hah; I loathed Lincoln. Part of my broader loathing of all things Spielberg. I don’t think it does actually celebrate institutions, exactly. It celebrates Lincoln as white savior hero genius. Barf.

Andrew: My defense of Lincoln’s would be Adolph Reed’s, which is simply that it portrays politics and dealmaking as valuable and even dramatic activities, in contrast to a movie like Django Unchained which seems racially progressive but which actually personalizes both the critique of and solution to an institutional problem like slavery.

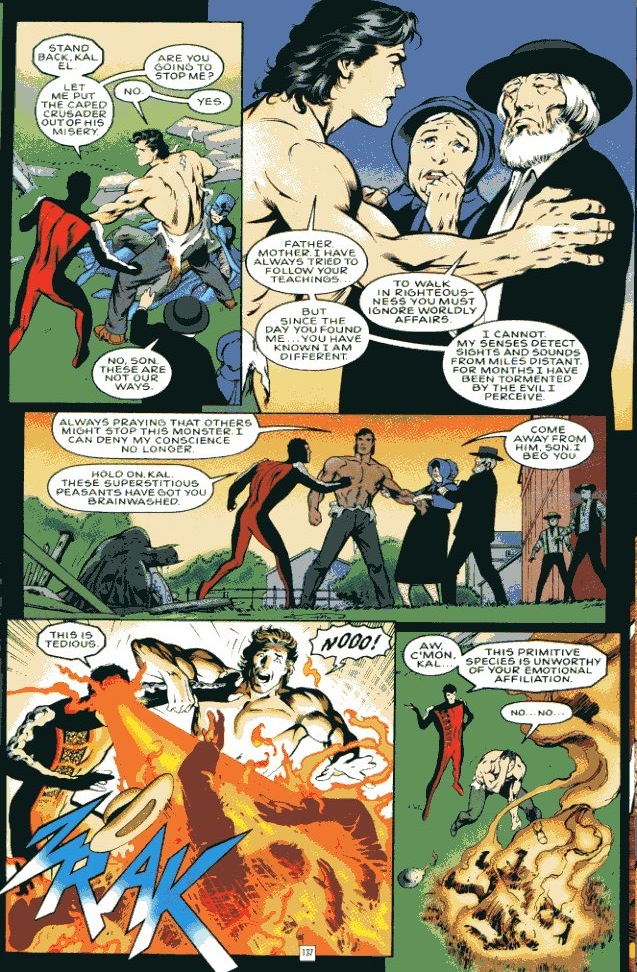

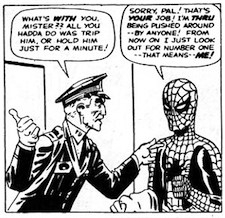

But to return to Watchmen in conclusion, I think this whole political question has a lot to do with the history of the superhero in which Moore and Gibbons play a key role. The pre-Watchmen history of the genre runs from 1938 or so to 1986, precisely the period in which Americans believed in the potential of government to make things better. In that respect, I tend to see the superhero as a figure for the New Deal state itself–a figure of extra-ordinary power committed to doing good in the world. The post-Watchmen idea of the superhero (in which Moore and Gibbons participate, even though they later come to bemoan it) as an obsessive or self-interested figure who claims to do good but in fact makes things worse nicely parallels, by the same token, neoliberal accounts of government.