This is a belated response to the Blog Carnival at Censor vs. Censure, hosted by Women Write About Comics.

_______

Free speech isn’t a moral good.

By that I don’t mean that free speech is evil. I just mean that, in itself, free speech isn’t an ideal to strive for; supporting free speech, as an end in itself, doesn’t make you a better person.

For many who identify as comics fans, or as art fans, or as libertarians, or as some intersection of all those things, this may seem like heresy. Supporting free speech is often touted as a kind of iconic sign of open-mindedness; a stand against the philistines. Alternately, or in addition, to be against free speech is seen as supporting tyranny and that mighty argument-quashing shibboleth, Big Brother.

There’s no doubt that Orwell and his speech that was free could fling a vicious slogan, thereby making all around him shut up. But putting aside the well-worn phrases, what does or doesn’t free speech actually do? “Free speech” is not a guide for how to treat your neighbor; it doesn’t tell you how to do unto others, or how to behave with kindness, or decency. It isn’t equality or love or “do not murder”. It is a subset of freedom perhaps — but even there the ground gets murky very quickly. If freedom means freedom to speak, it surely means, to the same degree, freedom not to listen; freedom to shout in the public square must, by its nature, impinge on other people’s freedom to go about their business in peace. Why should freedom of speech trump these other kinds of freedoms? What gives it extra special moral status, so that it takes precedence over other kinds of freedoms, or over kindness, or what have you?

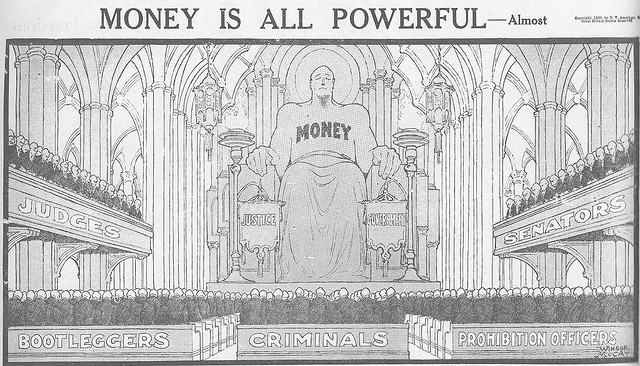

The answer is that there is no special moral status. What there is, is a special political status. Free speech is not a moral good, but the argument is that, in the modern community and the modern state, free speech is an invaluable tool for arriving at moral goods like equity, freedom, and happiness for all. Free speech creates a marketplace of ideas in which, the theory goes, the good ideas will gain traction and the bad will winnow away. Free speech is actually then allied as a moral good most closely not with freedom, but with truth.

This is a grand and appealing faith — but it is, still, just a faith. There’s no empirical evidence that free speech leads to truth, nor that it leads to more truth over time, nor that it creates happiness and freedom and equality, necessarily. The Bill of Rights was enshrined in a country built on slavery. The first amendment didn’t make slavery wither away either; on the contrary, slavery became if anything more entrenched over time. It was done away with not by argument, but by force of arms.

Force of arms isn’t a good in itself either, obviously. Lots of people, including me, think it’s an evil. And that’s really the best argument for freedom of speech; not that it is a good in itself, but that to stop it, you have to escalate violence. Speech can do harm, but the harm is generally less than the physical violence — such as restraining someone, or arresting them — you need to engage in to stop people from talking.

Speech can absolutely do good things, or lead to good. If I didn’t believe that, I wouldn’t bother writing. Speech didn’t get rid of slavery, but it did help set the ground for people to believe that getting rid of slavery was a worthwhile goal. It also, though, led to people being willing to defend slavery in the 1860s, and racism in the 1860s and on up to today. The goodness or value of speech can’t be separated from the content of speech. This is why the much brooted dictum “I disagree with what you say, but defend to your death the right to say it!” is largely incoherent. If content doesn’t matter, if you’re not even listening to what is said before you defend it, in what sense can you be said to actually disagree?

You could certainly argue that the state shouldn’t police speech, because using state power against people is cruel, violence is bad, and the people most likely to be stomped by the state are those with the least institutional power. You can argue that the government should not be able to censor speech, because that opens the door inevitably to government censoring criticism of itself, which vitiates the transparency necessary for a democracy to function. Those are reasonable arguments. But they’re not really an argument for free speech as a moral good in itself.

In fact, in practice, the call of “free speech” seems like it’s often a way, not to take a moral stance, but to avoid taking one. If you support free speech as a moral ideal in itself, you don’t have to think about the content of speech at all. The nature of the speech — what it’s saying — is beside the point. Oddly, the call of “free speech” tends to end discussion. Once you’ve praised the speech for being free, what’s left to say? It doesn’t matter what you mean, it only matters that you mean something. Whether it’s Hitler or Ghandhi talking, it’s speech. Defend it!

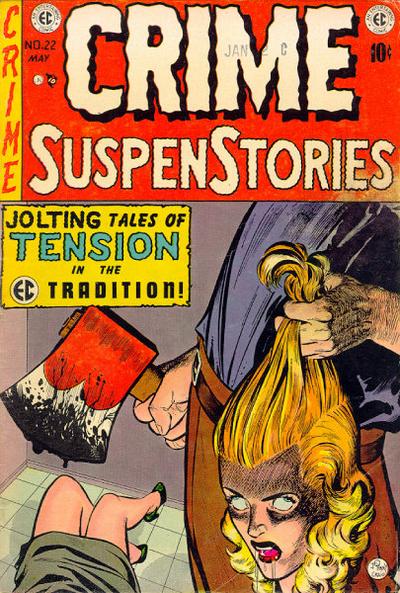

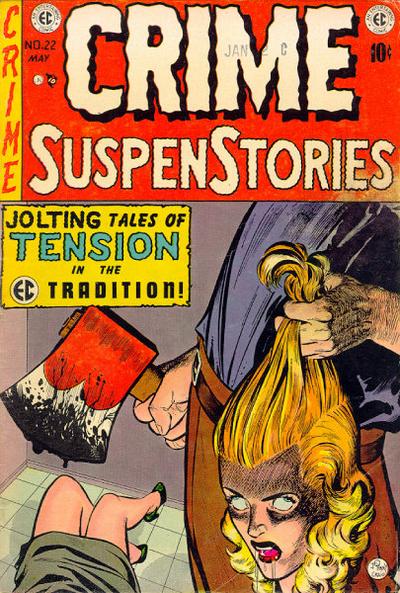

But if free speech isn’t a moral good in itself, it becomes, not an ideal, but a tool, which, like any tool, can be used for good or ill. That doesn’t mean that we should lock in prison people who say things we don’t like, not least because locking people in prison is an evil as well, and often a worse one than the wrongs it purports to punish. But it does mean that if you defend vile shit, you’re just defending vile shit — though what is and isn’t vile shit can, of course, be up for vigorous debate. That debate seems like it should be on the merits of the speech itself, though, and not on the grounds that everyone should be able to say whatever they want in every venue. Still less should it be on the grounds that vile speech is especially valuable because of its very vileness. You don’t become a better person by championing revenge porn.

Again, morality isn’t legality, and for many of the reasons I’ve discussed here I think making speech illegal is in most circumstances a bad idea. But expression in itself isn’t a good, or a guarantor of virtue. Morality inheres in what you say, not in having said it.