The Comics and Music roundtable index is here.

______________

Suggested Background

Alphonse Mucha was a cartoonist.

Unnecessary Personal History, or, I Did That

I turned 33 last December. In the past fifteen years I’ve been employed as, among other things, a car washer, a janitor, a furniture pricer, an art model, a candy delivery man, an audio engineer, a high school art teacher, a graphic designer, an illustrator, a mercenary Christmas caroler, a writer, a cartoonist, a musician.

Comics and Music

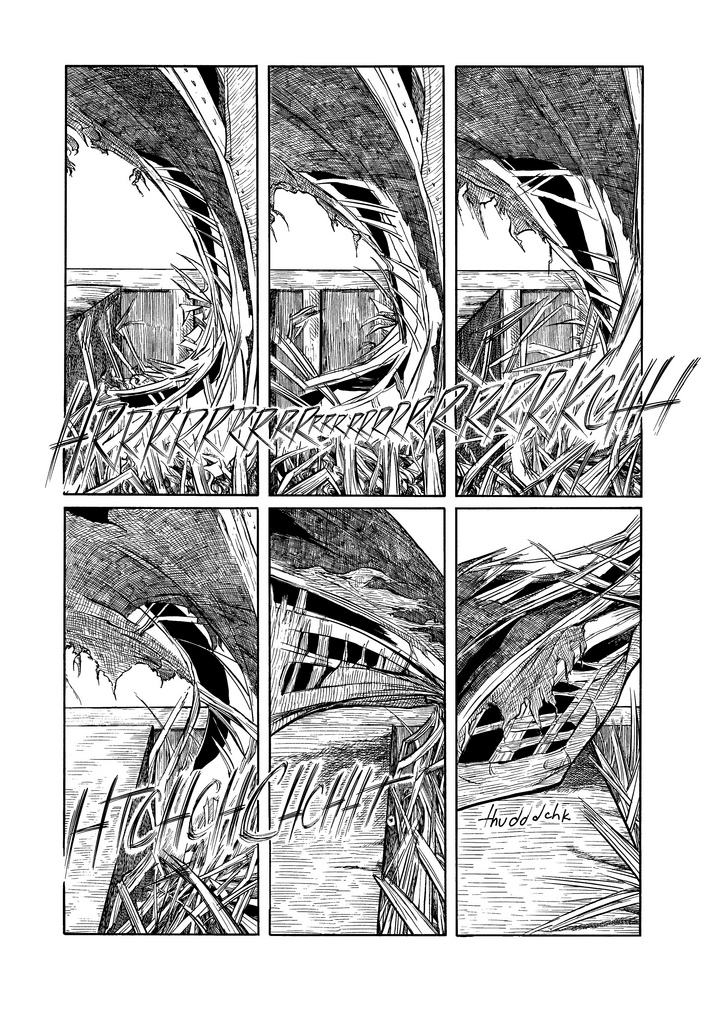

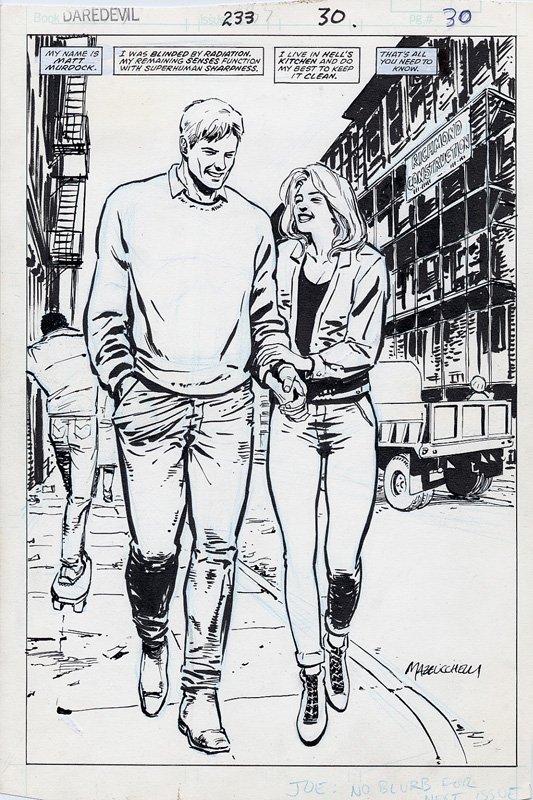

It took years to develop the cartooning skills that I have, hours crammed in to a brutal teaching schedule, thousands of hours at the white drafting table while the world continued on outside. All that’s left now is a few scattered short stories and several hundred pages of a graphic novel in a box in a storage unit in Olympia, Washington. Oh, and the paid work, which came at the tail end of my interest in cartooning– 50 pages worth of deadline-motivated inking assistance on David Lasky and Frank Young’s Carter Family: Don’t Forget This Song, and another 30 pages or so on their Oregon Trail book a year earlier. (I’m not counting plenty of paid illustration work—more on that below.)

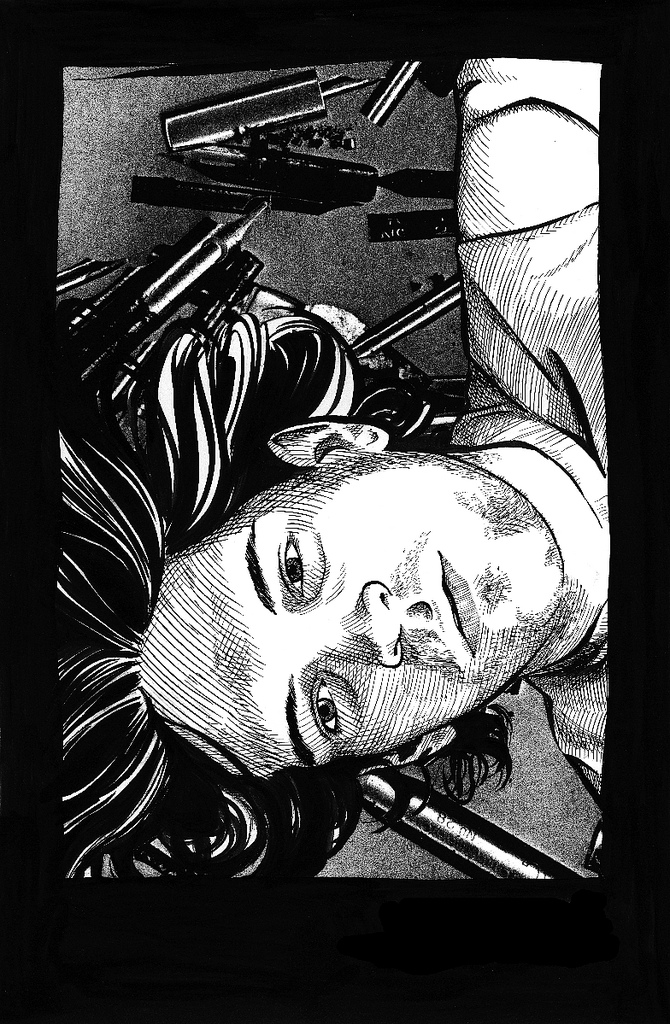

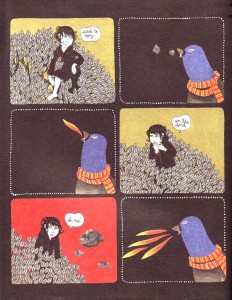

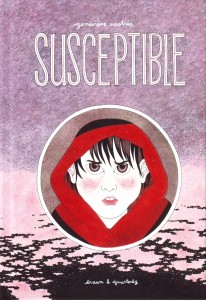

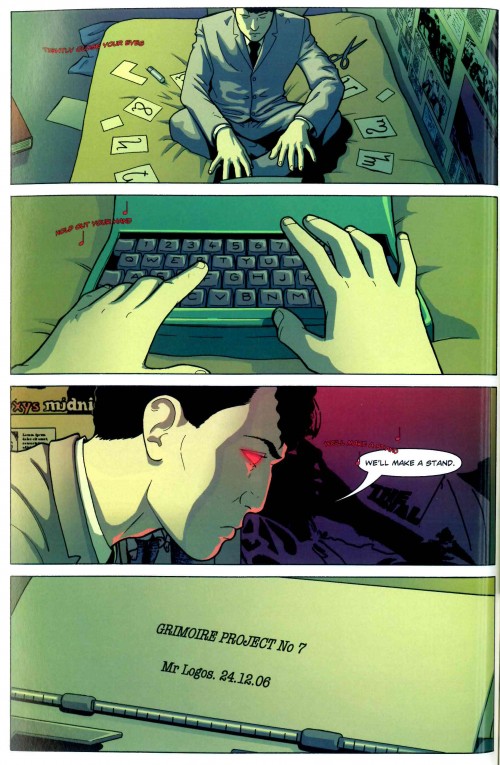

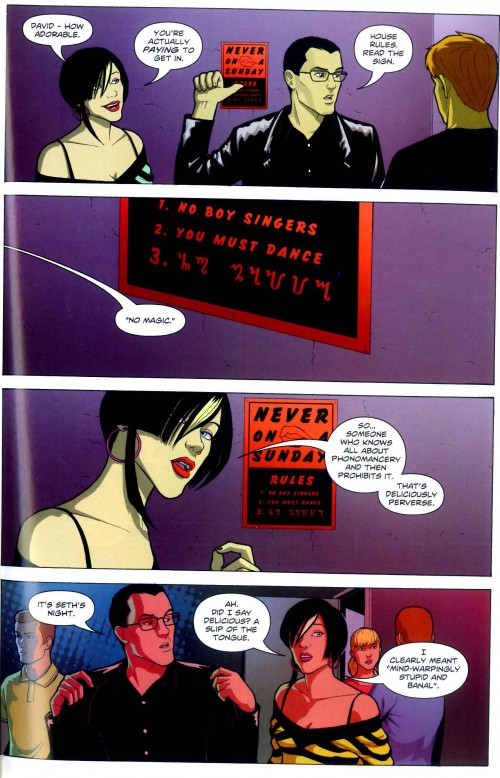

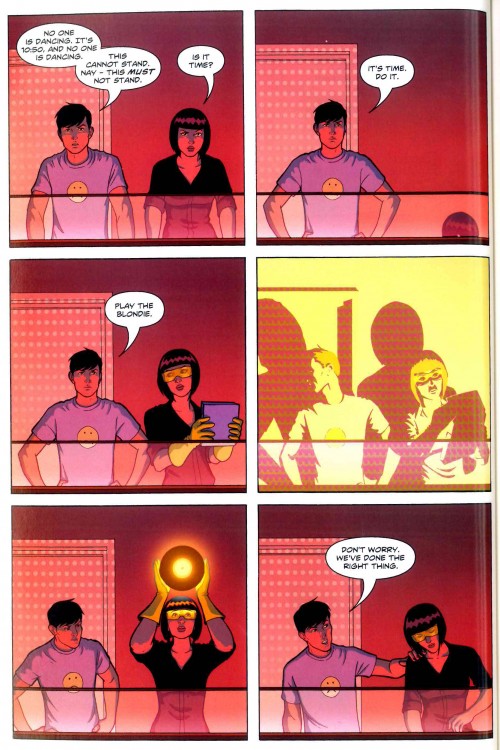

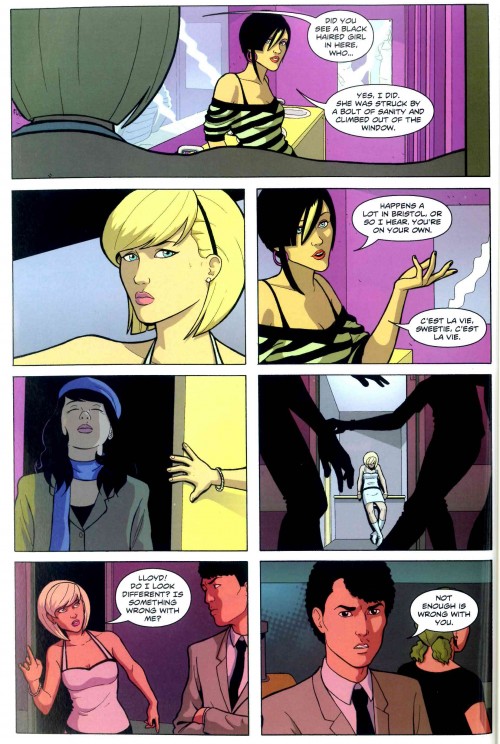

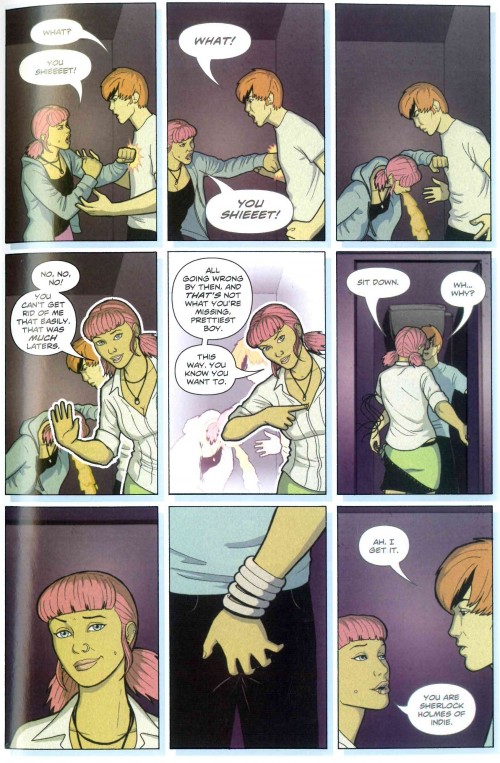

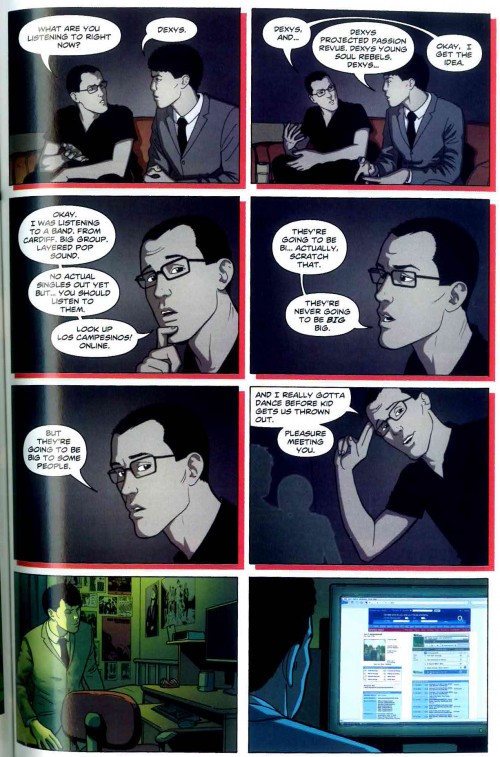

from the unfinished Discards.

When I think back to those years, what I mainly remember is how little agency I felt in my own life at the time, how many decisions seemed like inevitabilities, the way that something had to be versus how I might want it to be. In that light it’s not hard to imagine the appeal of cartooning, of taking the imaginary and making it real on the page. There’s nothing you can’t control in that world that is nothing but promise before pencil hits paper, assuming the skills are in place. And even developing those skills necessary gave me back an illusion of control. The skills, the work, these were the things I could apply myself to. The people on the paper.

Punk or Liszt

It’s an accident of history and aesthetics that aligned indie comics and various punk rock or indie rock scenes. From a production standpoint, Jaime Hernandez has more in common with classical pianists than, say, a bass player in a hardcore band.

For a million-seller manga-ka, drawing comics might be more like being on a baseball team: for a cartoonist in the North American “commercial comics” scene, it’s more like pulling a sleigh with three other horses and knowing that any of you might beshot and eaten at any minute, and while the survival rates isn’t good, I’m sure the omnipresent threat of disaster lends things a certain excitement– but for the rest of us out there, making comics is a lonely, lonely process.

It seems crazy, in a way, working for 5 to 15 hours on a page that will probably be read by its audience in less than 5 seconds. By contrast, a classical pianist might put in 15 to 50 hours a week of practice, alone, as solitary as the cartoonist in question. And a tremendous amount of that practice might be devoted to just a few seconds of the piece, a single difficult run. But even if the pianist plays with no other musicians, when it’s time to perform, their audience is in the room with them, ready to receive their performance. A performance, then, is still partly exchange. The cartoonist, even if she’s fortunate enough to have found an audience, is denied even that. (Unless, of course, her friends are willing to be watched while they flip through her new effort.)

What Type of Nib? I’d Suggest the One Shaped Like a Guitar, or Maybe A Dulcimer

Seriously, kid. You’re telling me you have equal enthusiasm for music and for comics, have put some time into both and have found your interest aligns pretty well with your early aptitude? Well, I respectfully submit that you might be happier making a joyful noise with your fellow human beings than spending the next decade making tiny lines on paper to prepare yourself for better making tiny lines on paper.

What’s that? Money? Oh, don’t worry about that part—there’s no money in either. At least not directly. While there are still theoretically people making a living off of playing music, doing so under your own terms and without the supplementary work of teaching or wedding performance etc is about as likely as … well, as making a living as a cartoonist without doing the same.

Varied income sources for some of the best cartoonists of my acquaintance–

- freelance illustration for local weeklies, until they decided to stop paying

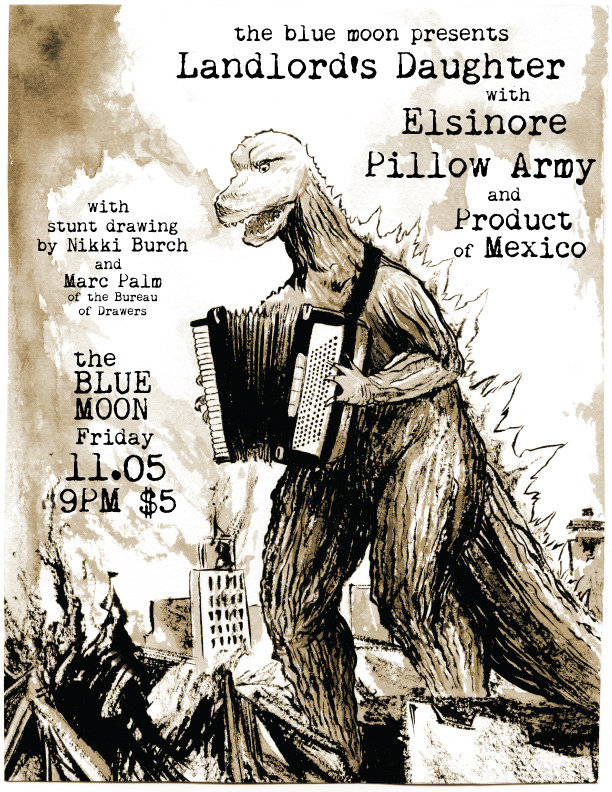

- posters for local bands, until they decided to stop paying (possibly because they’re not getting paid either)

- freelance illustration for various cell phone and video game companies, which mostly still pay

- freelance illustration for various ego maniacal individuals via craigslist

- selling original artwork for an entire book to a private collector prior to the book existing, in order to enable the book to be produced in the first place

- making pizza

Q. What do you call a drummer [cartoonist] who just broke up with his girlfriend?

Making A Joyful Noise

I’m biased. I associate my years of dedicated cartooning with the most difficult and inward time of my life, and I associate making music with all of the things that have brought me joy—my closest friends, the love of my life, bringing happiness to other people, learning to be the kind of person who can open himself to others and not retreat in the face of sentiment.

And although there was a lot of upfront investment in the skills involved, over time I found that those skills could continue to develop in the presence of other human beings, that just playing music with other people made me better at playing music.

It’s not that I never had any dissatisfaction with playing music. I hated the bar scene. I hated being an alcohol salesman, a cigarette pimp. I hated the atmosphere, the cigarette hangover, the rock and roll hangover of the ringing ears and wheezy breathing, like I’d spent the night firing a gun and sucking on a tail pipe. I hated competing for attention, hated the soup of bands and bookers and cred payola, hated the omnipresence of the array of measuring sticks of cool. That was, after all, some of the appeal of comics for me in the first place– ten years ago, anyway, it seemed like there was virtually no competition, and so many hills to climb and plant your flag on.

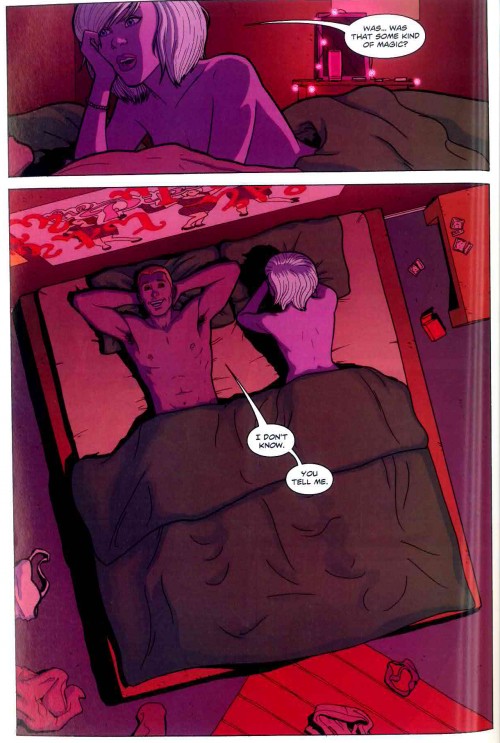

Caution: Sentiment Ahead

But two years ago I met her and it was a blur, a whirl-wind, if you prefer, and both are cliches but either describes the feeling perfectly, everything happening at once, no way to really sort through all of the rush other than staring at the calendar and dumbly repeating “we met each other WHEN?” She was a busker, a fiddle player and vocalist and crafter of the most delicate songs I had ever heard, and it seemed impossible that we would do anything other than dedicate ourselves to making things together, to each other.

And that’s what we’ve done since. We haven’t had a home since September of last year, but we’ve played for tens of thousands of people, mostly on the streets of Italy, with a winter of writing and pub gigs in Florida. It’s a nice life, although like everything else the writing is sometimes delayed by the rest, the pressure to perform as often as the opportunity presents itself, the chaos of travel and negotiation and occasional arguments in a language we understand only a little and speak even less.

But the songs continue to come, and the work continues to develop, at it’s own pace. No forcing, but still continuous effort, always more improvement, but this time, in tandem with another human being.

And, as always, other art forms beckon.