The index to the Comics and Music roundtable is here.

______________________

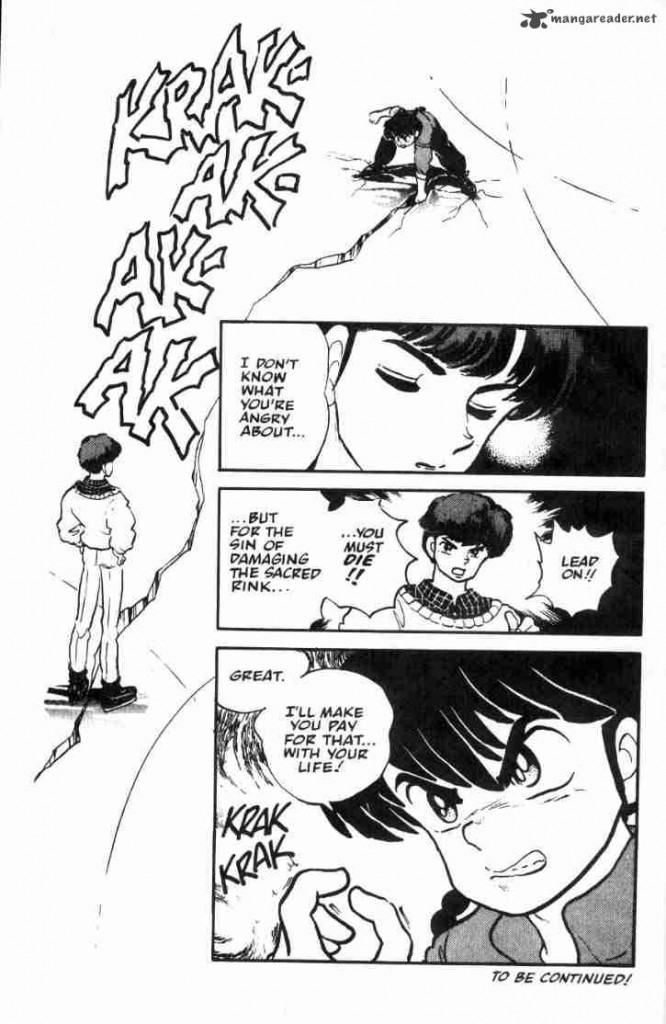

The word “superman” premiered in a play about a modern Don Juan. So it’s fitting that most Superman songs are love songs. Despite all of its anti-marriage ubermensch rhetoric (marriage is an obstacle to ideal breeding blah blah blah), George Bernard Shaw’s 1904 Man and Superman ends when the girl lassos her Clark in the final act. Since then, lovedumb Supermen have been crooning through the decades.

Here are their high notes:

5. The Kinks, “(Wish I Could Fly Like) Superman”

The Kinks with a disco beat? It was 1979 and so not entirely their fault. I didn’t hear the song till their live album a year later. The year the Kinks were ret-conned into Rock continuity. That’s right, the Kinks did not exist before 1980. Van Halen’s “You Really Got Me” wasn’t a cover until it appeared on One for the Road, an album of rock classics retroactively inserted into the AOR timeline. First time I heard “Lola” from a radio speaker, a stadium of fans were la-la-la-ing the chorus. I felt like the lone survivor from some parallel universe. I’d been listening to Pittsburgh’s WDVD for a couple of years, memorizing playlists, band line-ups, discographies. Reallocating the area of my brain previously devoted to superhero teams and baseball rosters. The Kinks? Never heard of them. But suddenly there they are strumming between the Who and the Rolling Stones since the 60s. I pretended like nothing was wrong. The Kinks? Sure, yeah, love ‘em. That’s Adolescent Survival 101. Next thing my first-ever girlfriend and I are cheering them in the Civic Arena, and wearing our matching concert T-shirts on our anniversary every month after clueless month. If everyone jumps off a cliff, of course you jump off too. Doesn’t matter if you can fly or not.

“Hey girl we’ve got to get out of this place

There’s got to be something better than this

I need you, but I hate to see you this way

If I were superman then we’d fly away”

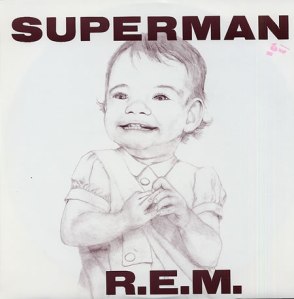

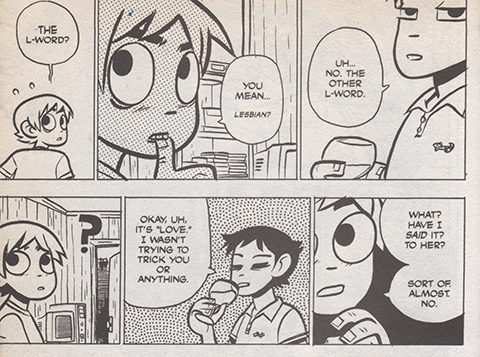

4. R.E.M., “Superman”

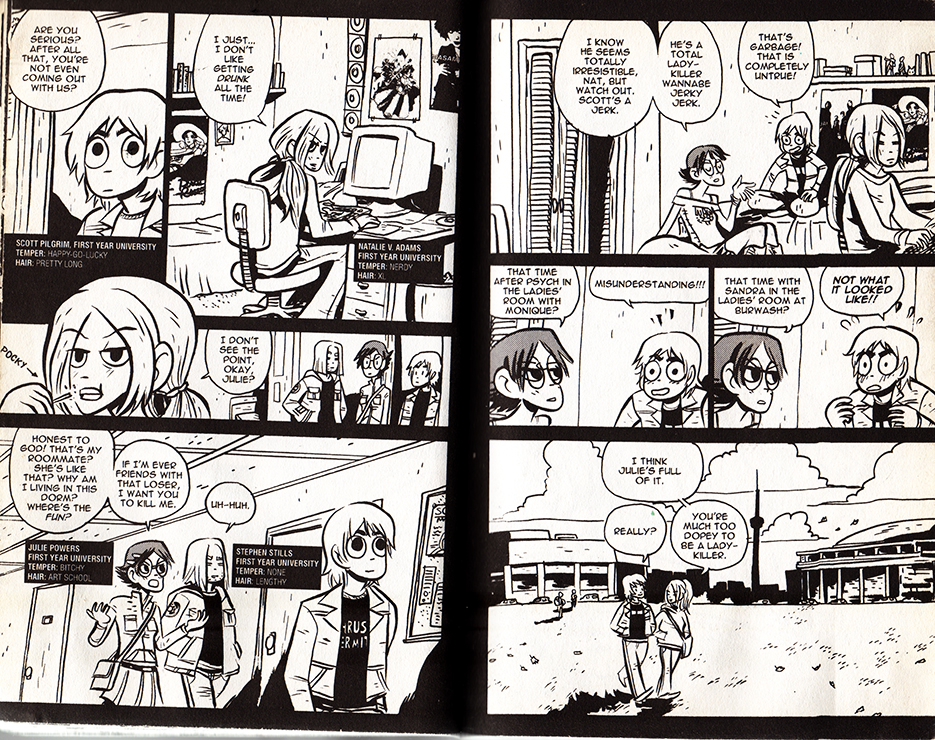

I had way too many Black Sabbath albums to get my head around R.E.M in high school, but college was another planet. The year I first kissed Lesley Wheeler. We meet in a student center utility closet moonlighting as our literary magazine office space. She liked R.E.M. and so soon I did too. Apparently this “Superman” was a cover of an obscure 1969 single from some band named the Clique. Another ret-con, but nobody was pretending otherwise this time. Despite all the Superman hubris, it’s an underdog’s song. Mike Mills, the bassist, sings lead. Michael Stipe is slouching by a back-up microphone, a cup of coffee in his hand, tambourine in the other. Lesley was dating someone else, but we kissed once, during a party in her honors dorm, and then she flew away for a semester abroad. R.E.M. wouldn’t have their breakthrough till the following year, when it wasn’t just our college DJs twirling “It’s the End of the World as We Know It (And I Feel Fine).” The whole multiverse was about to explode. I might not have had her grades, her scholarship, none of the spark bursting through her poems. But I knew to fly after her. I knew what was happening.

“You don’t really love that guy you make it with now do you?

I know you don’t love that guy ’cause I can see right through you.

If you go a million miles away I’ll track you down girl.

Trust me when I say I know the pathway to your heart.”

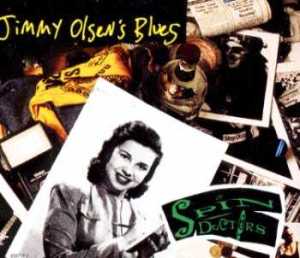

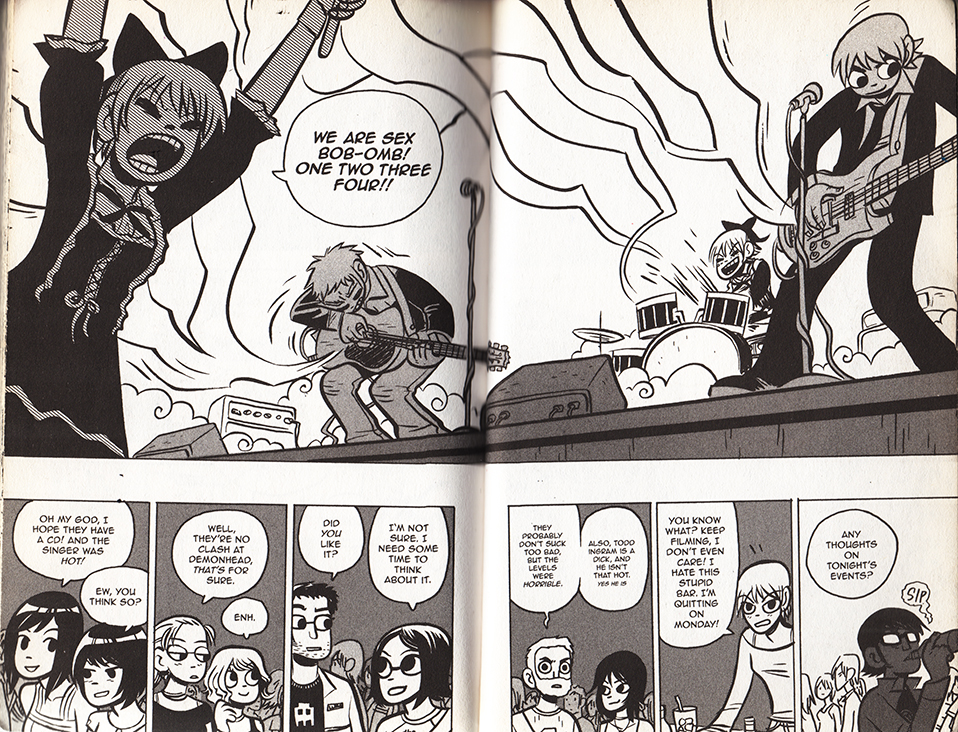

3. Spin Doctors, “Jimmy Olsen’s Blues”

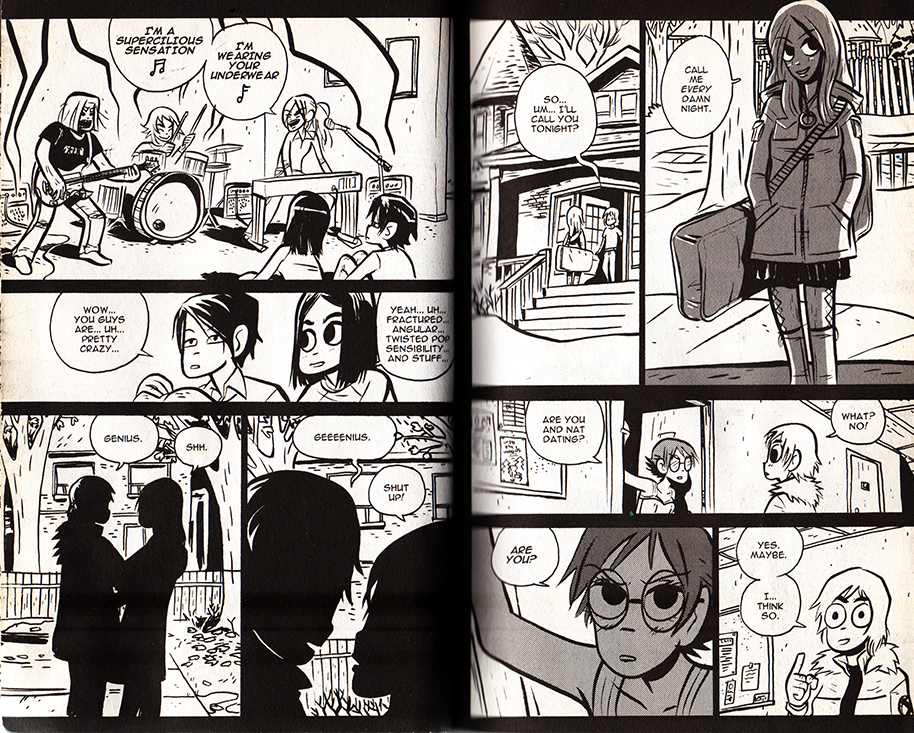

Our kitchen calendar said 1991, but it sounds like the 70s rebooted, Steve Miller Band, Aerosmith, even a little Lynyrd Skynyrd, all of it seamlessly synched together by the dance beat thumpings of a double bass drum kit. An analog amalgam at the dawn of the digital sample. When Lesley and I moved in together that year, the hardest part was merging our record collections, deciding whose redundant copy of which David Bowie was less scratched, less nostalgically vital. I’d thought CDs were a passing phase, like 8-tracks, but was now giving in to fate. A rotating CD rack perched on a speaker the size of an end table. Pocketful of Kryptonite sold 5 million, its four singles muscling through the airwaves. We hummed them in the car, in the kitchen, in the backs of our heads as we drifted asleep. We found a caterer, a baker, a quaint historical house to rent for an August afternoon. It rained in the morning, pushed the heat back all day, then poured again that night as we drove back to our apartment with the wedding loot. The Spin Doctors’ second album flopped. Doesn’t matter. After the readings and the vows, I slotted Kryptonite into the reception CD player with some other new releases and hit “random.”

“Lois Lane please put me in your plan

Yeah, Lois Lane you don’t need no Super Man

Come on downtown and stay with me tonight

I got a pocket full of kryptonite”

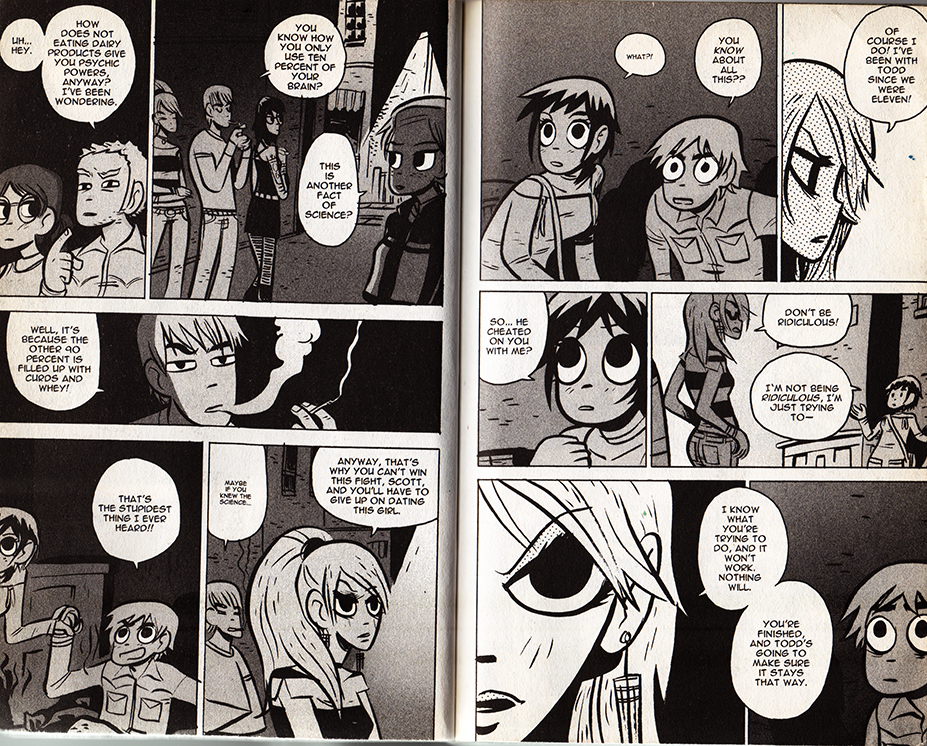

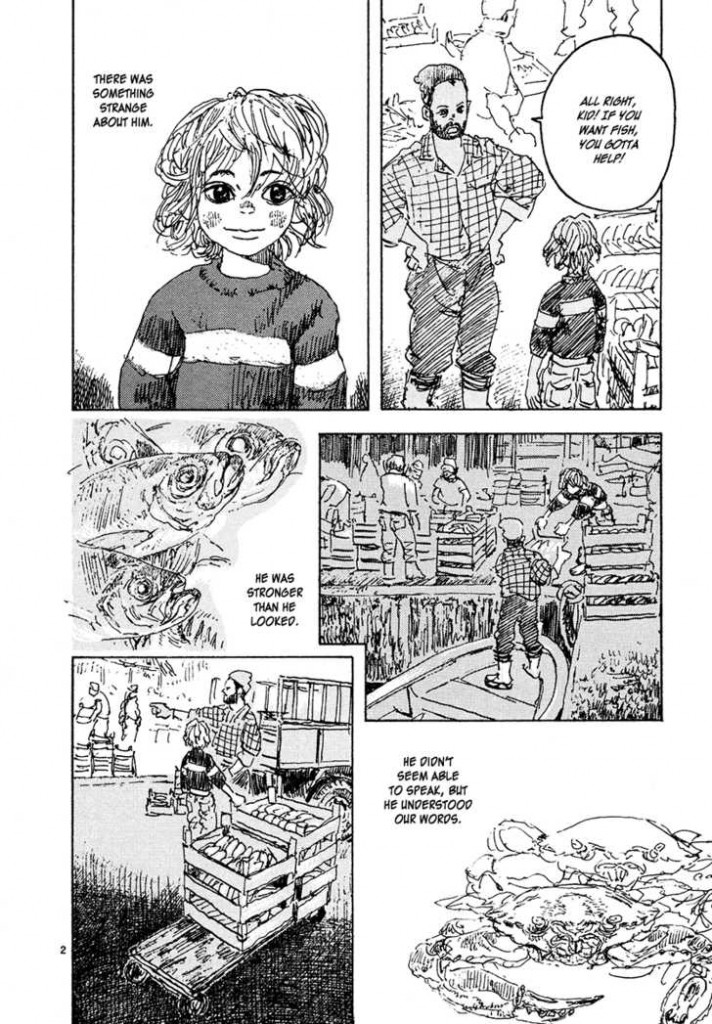

2. Lazlo Bane, “I’m no superman”

Actor Zach Braff discovered the song, an obscure indie tune that premiered in a 14-second snippet over the opening credits of Scrubs before it made it to the band’s second album. Lazlo Bane (I’d thought it was a person) originally said no to the TV deal. Didn’t want to sell out. But somebody must have talked some sense into them. Three weeks after 9/11, a sitcom’s exactly what the country needed. Lesley and I had just moved into the house we live in now. American flags flapped up and down the block. Our son was one, our daughter four. We had to explain to them that terrorists were not going to blow up skyscrapers in Lexington, VA. We didn’t have any. We’d moved to Smallville, after rocketing away from the New Jersey Metropolis where we’d fallen for each other. We hunkered through Afghanistan, Iraq, prayed Obama could save us all. NBC dropped Scrubs in 2009, but ABC rebooted it for a ninth and final season. They shuffled the cast and hired WAZ (I’d thought he was a band) to rerecord the theme. It didn’t matter. We’d stopped watching years before.

“You’ve crossed the finish line

Won the race but lost your mind

Was it worth it after all

I need you here with me

Cause love is all we need

Just take a hold of the hand that breaks the fall”

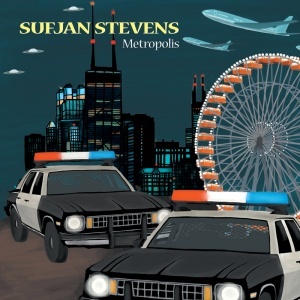

1. Sufjan Stevens, “The Man of Metropolis Steals Our Hearts”

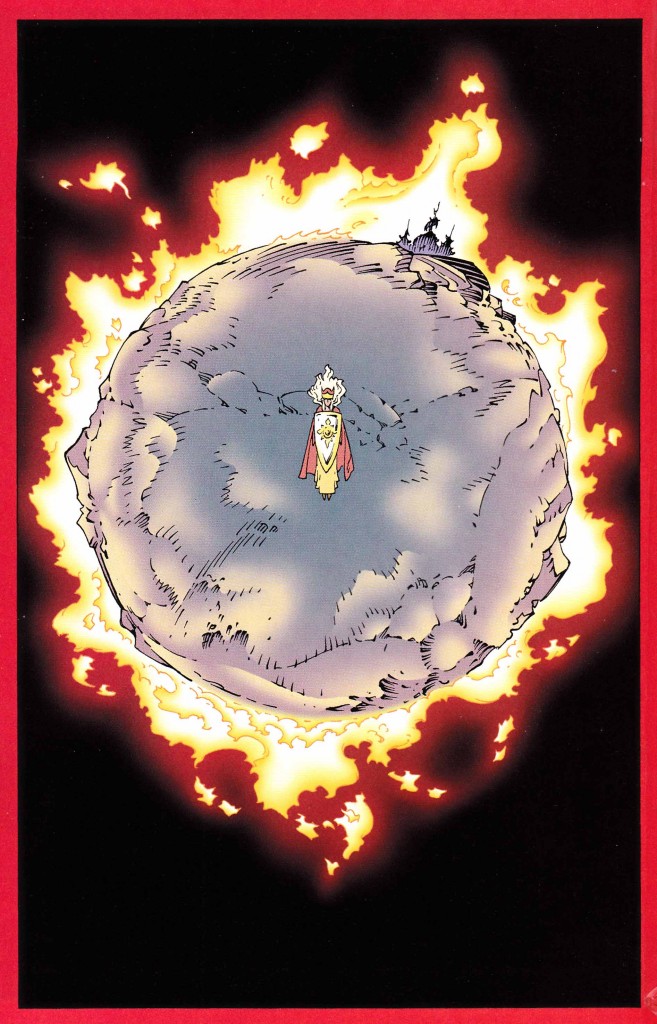

I thought Sufjan was Cat Stevens recording as his Muslim alter ego (which is Yusuf Islam). I was never hip, but now I’m old too. My son is twelve, my daughter sixteen. She sits across the dinner table, describing mutant subgenres I never dreamed of. I had to borrow the album from my metrosexual neighbor. It was already old, part of Stevens’ abandoned project to record fifty albums about fifty states. Apparently, Smallville is in Illinois. A legal dispute delayed the 2005 release. They had to put a sticker over Superman on the cover art. It came out in vinyl first—technology made cool by extinction. Our 80s vinyl lines the back shelf of our closet. We play them during dinner sometimes, the needle crackling like a victrola through speakers the size of furniture. The Illinois CD has no sticker, just a blank space, the past waiting to be rebooted again. Clark Kent used to be a joke, a Kryptonian’s caricature of humanity. They reversed that in the 80s, made the boy grunt his way through adolescence like the rest of us. I don’t know what the story is now.

“Only a real man can be a lover

If he had hands to lend us all over

We celebrate our sense of each other

We have a lot to give one another”

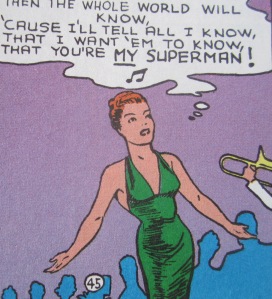

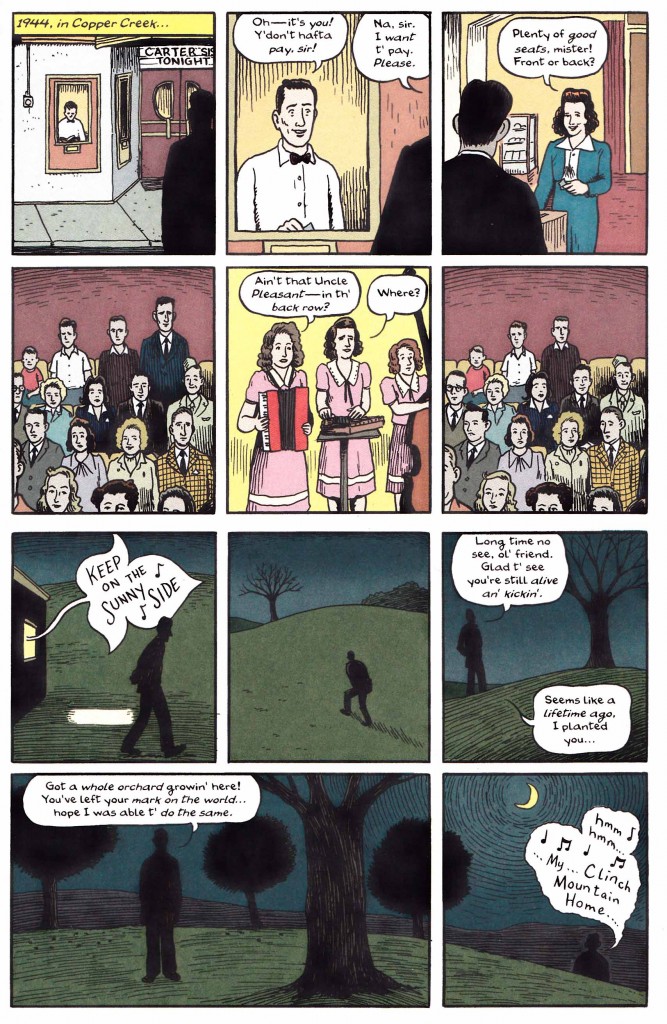

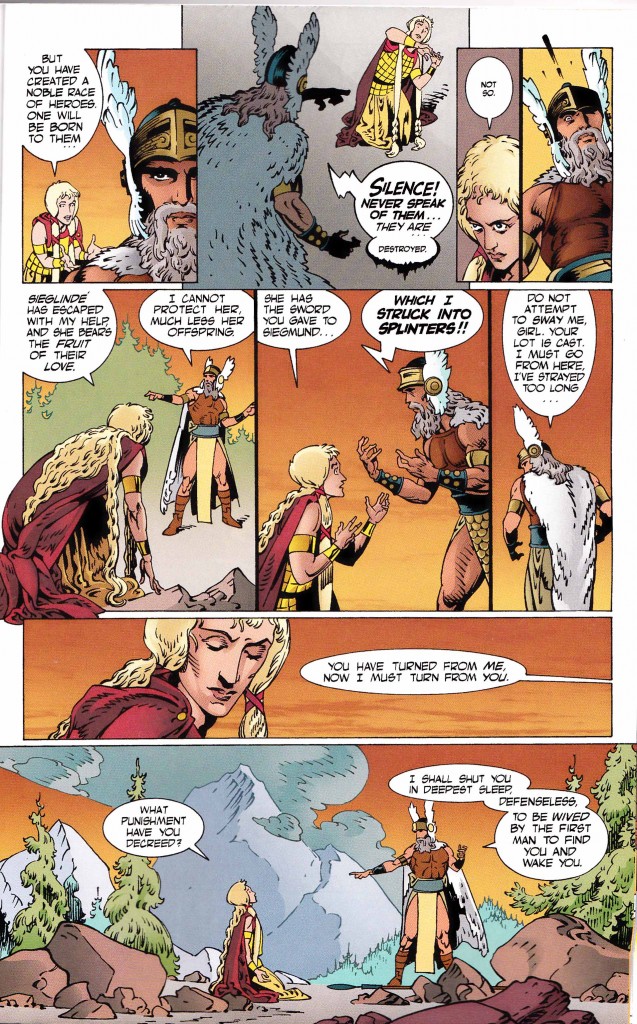

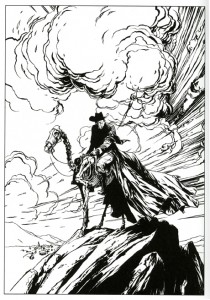

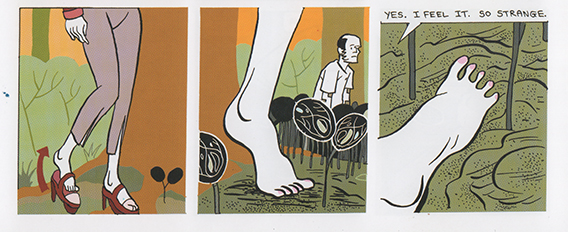

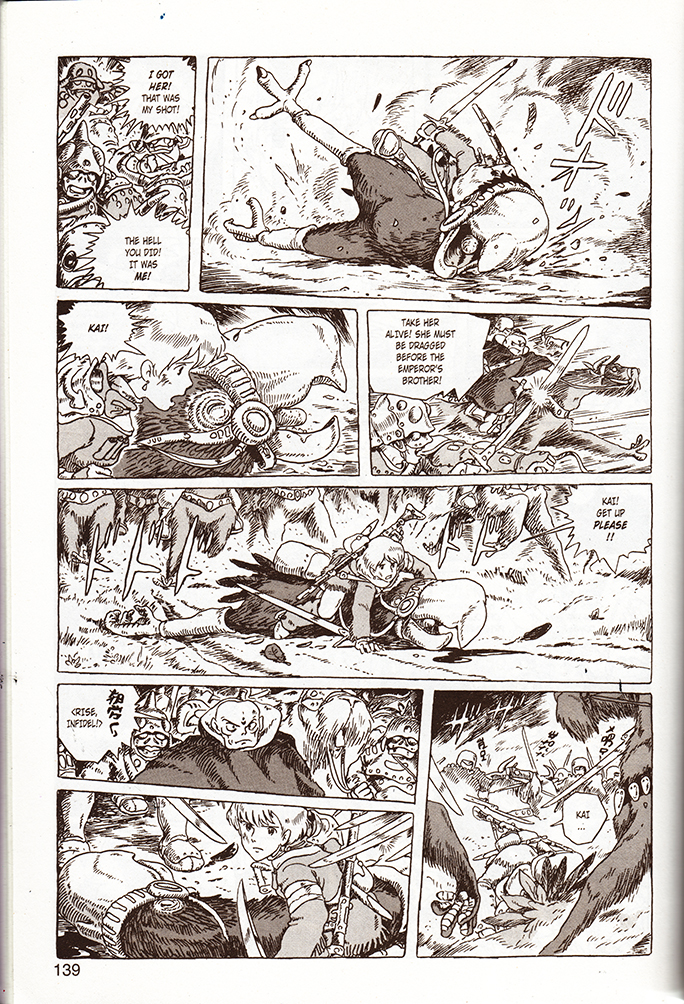

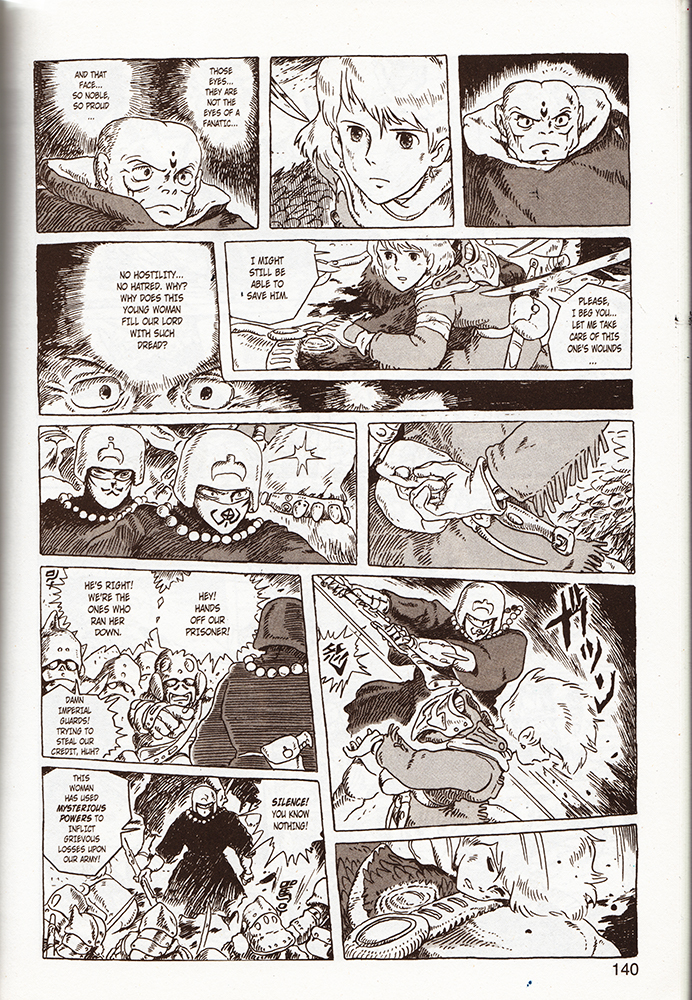

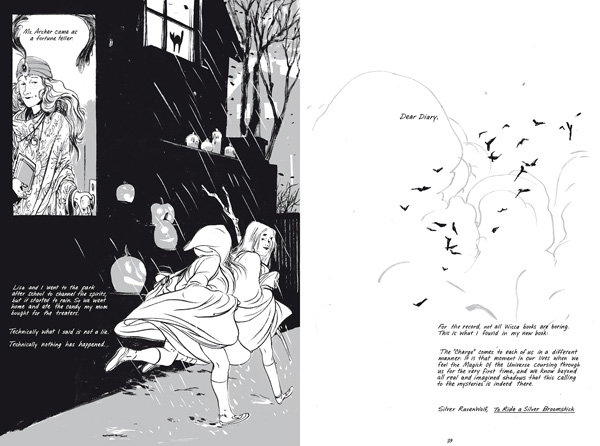

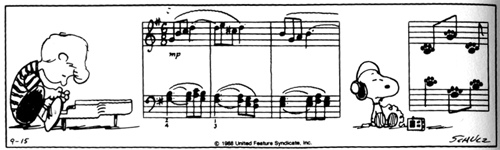

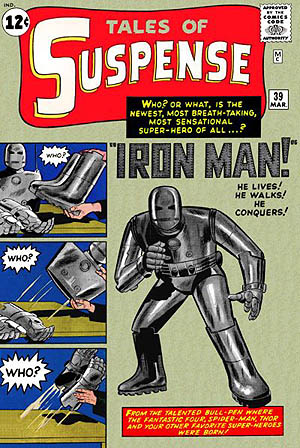

6. BONUS TRACK: “You’re a Superman!”

I don’t know the singer’s name, just that she’s a redhead in a green dress. The nightclub doesn’t have a name either, but Lois Lane is there, ready to scoop Clark on an exclusive interview with Superman. Clark thinks it’s their first date. “Tonight I’m going to introduce a song that is sure to be a hit,” the singer announces. “Swing it, boys!” Action Comics No. 6, cover date November 1938. The Andrew Sisters had a hit that year. So did Ella Fitzgerald. It’s her voice I hear over Joe Shuster’s drawings. It’s no ballad. Just look at the angle of the trombone silhouetted in the background. Jerry Siegel is writing the love song no one ever sung to him. Girls found him creepy in high school. But now with Superman going into newspaper syndication, the girl next door—literally, her name is Bella, and she lives across the street from the Siegels—suddenly she’s not out of his bold, new reach. They’ll be married in a year, divorced a decade after that. It’s the only perfect Superman song, unblemished by its soundless performance. “Clark glances sideways at Lois. Enthralled by the magic of the song, her eyes have a distant, charmed look . . .”

“You’re a Superman!

You can make my heart leap,

Ten thousand feet!

“You’re a Superman!

But I’m the one girl who kin,

Get under your skin!

“When you crush me in your arms, I must reveal

I’m only flesh and blood and not resisteless steel!

“You’re a Superman!

Your ardour’s stronger than,

A human man’s!

“You’re a Superman!

And when you spring to me,

I am in ecstasy!

“Some day you’re gonna leap,

To the altar at my feet . . .

Then the whole world will know,

‘Cause I’ll tell all I know,

That I want ‘em to know,

That you’re My Superman!”