The index to the Indie Comics vs. Context roundtable is here.

____________

I discovered Jason Karns’ Fukitor thanks to the controversy in The Comics Journal thread over his use of racist imagery. That I ordered some issues based on those questionable images probably hints at my take on the controversy. Bigotry can be funny. It wasn’t too long ago, for example, that I was chortling through a documentary on Fred Phelps’ Westboro Baptist Church (I believe it’s called Fall from Grace, available on Netflix). They’re the ‘God hates fags’ family/church who express opposition to the homosexual control of America through a series of signs — often presented at funerals of soldiers and rock stars — on which they thank God for AIDS and pray for more dead soldiers. Even the KKK finds their ideology objectionable (really). It’s hard not to laugh at that. You really can’t caricature the Phelps clan. How could their message be any more risible? Nor will arguing with such people do much good if they’re too extreme for white power groups. Some belief systems are too nuts to take seriously. I don’t mean that we shouldn’t worry about hate groups and religious extremists, just that it would be a bit silly to treat what they say or believe within the parameters of a rational discourse. You don’t need to argue with them, just keep away — and laugh from a safe distance. The Westboro Church would fit right into a Fukitor storyline, if Karns ever felt like “analyzing” Christianity. His aesthetic is well suited. Phelps’ religious justification for his homophobia is about as convincing and complicated as the following (only with hellspawn that are to be more feared for being less straight):

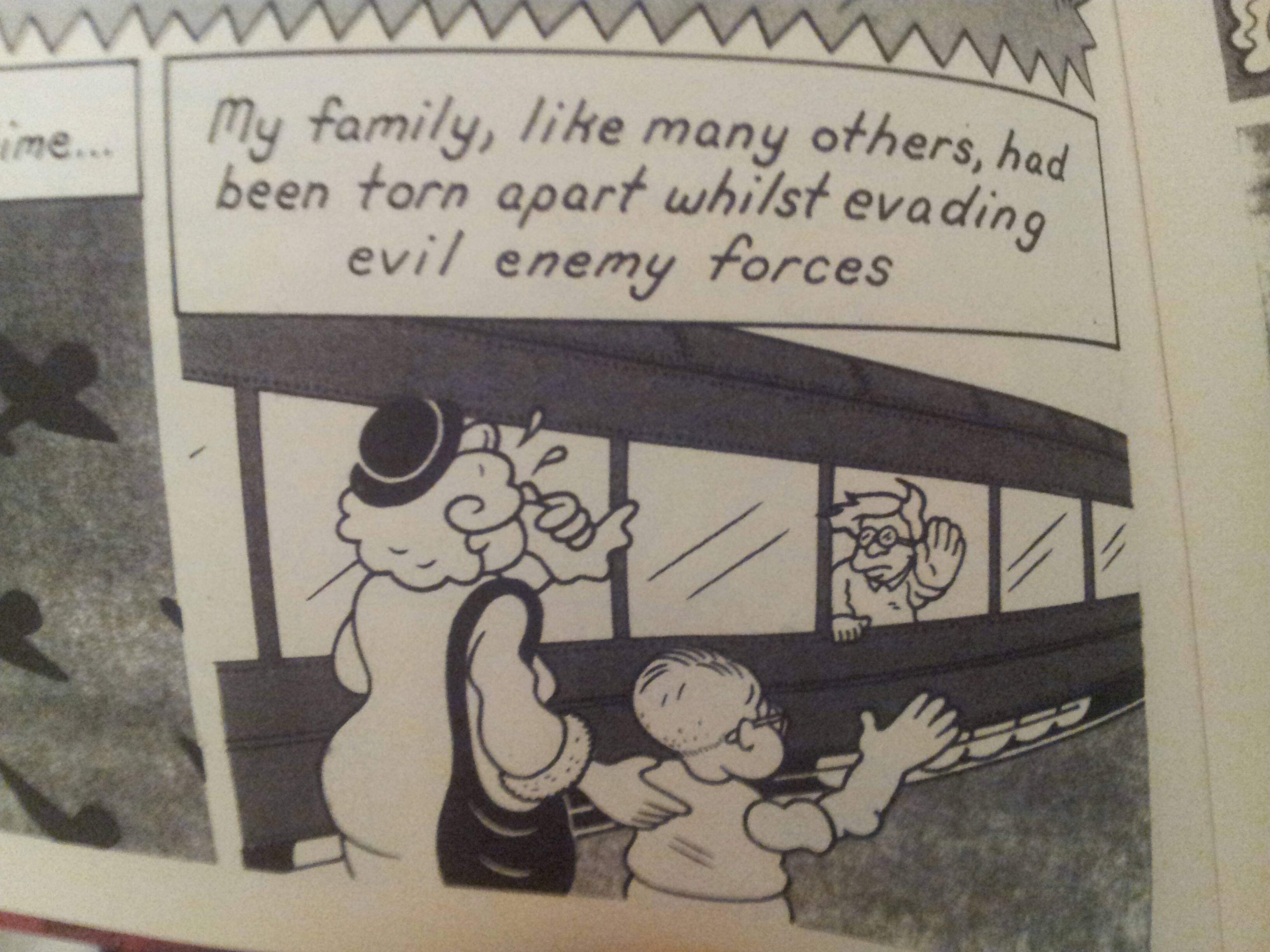

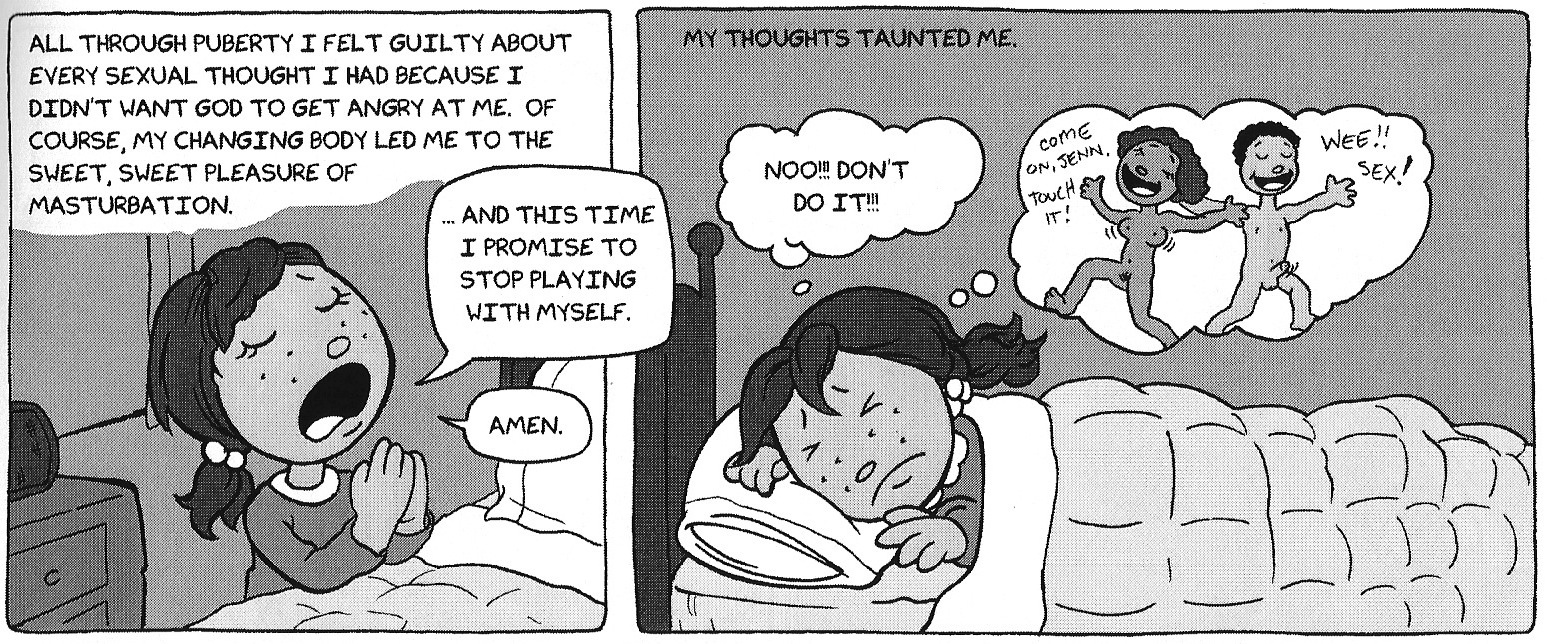

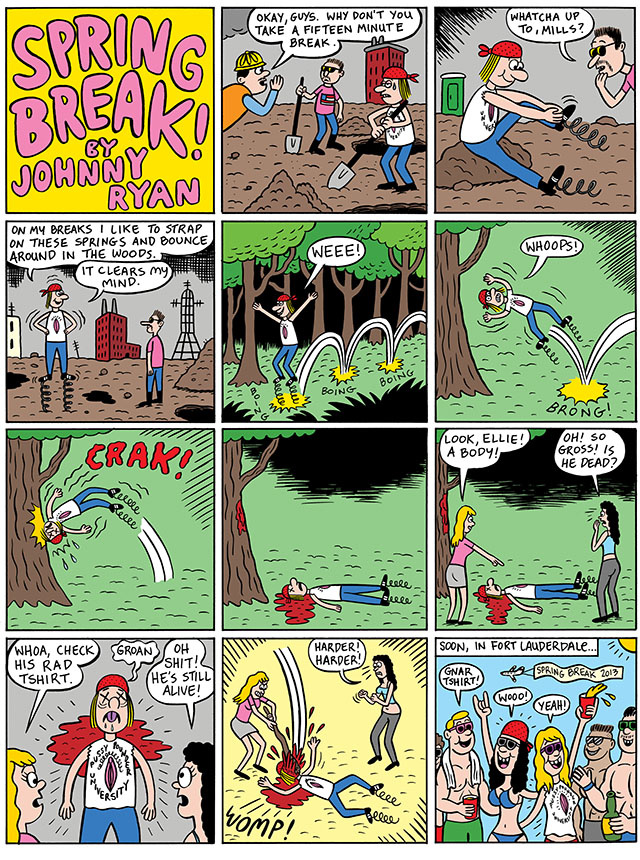

Fukitor 7, “Doctor Werewolf versus the Zombie Sadists”

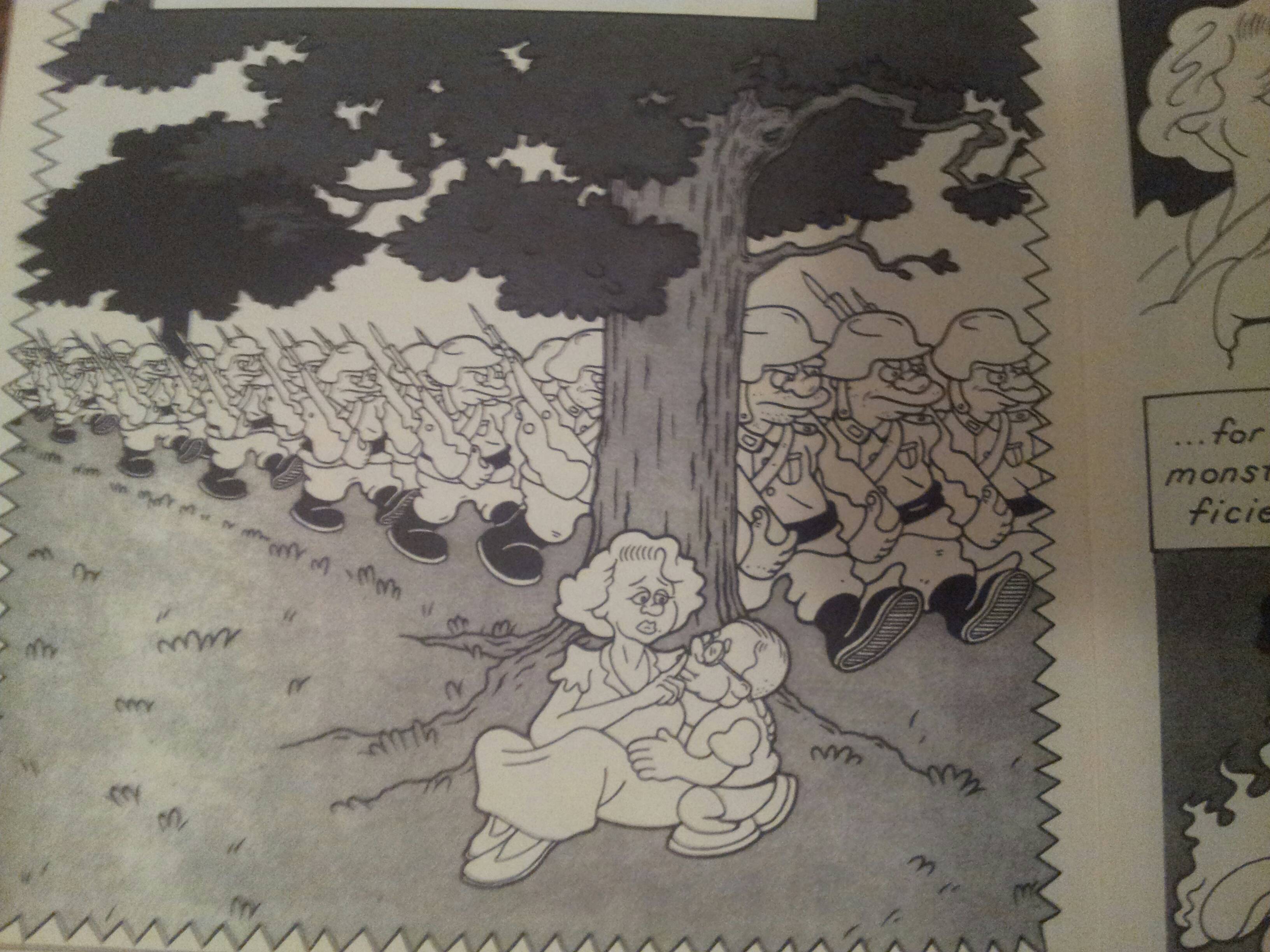

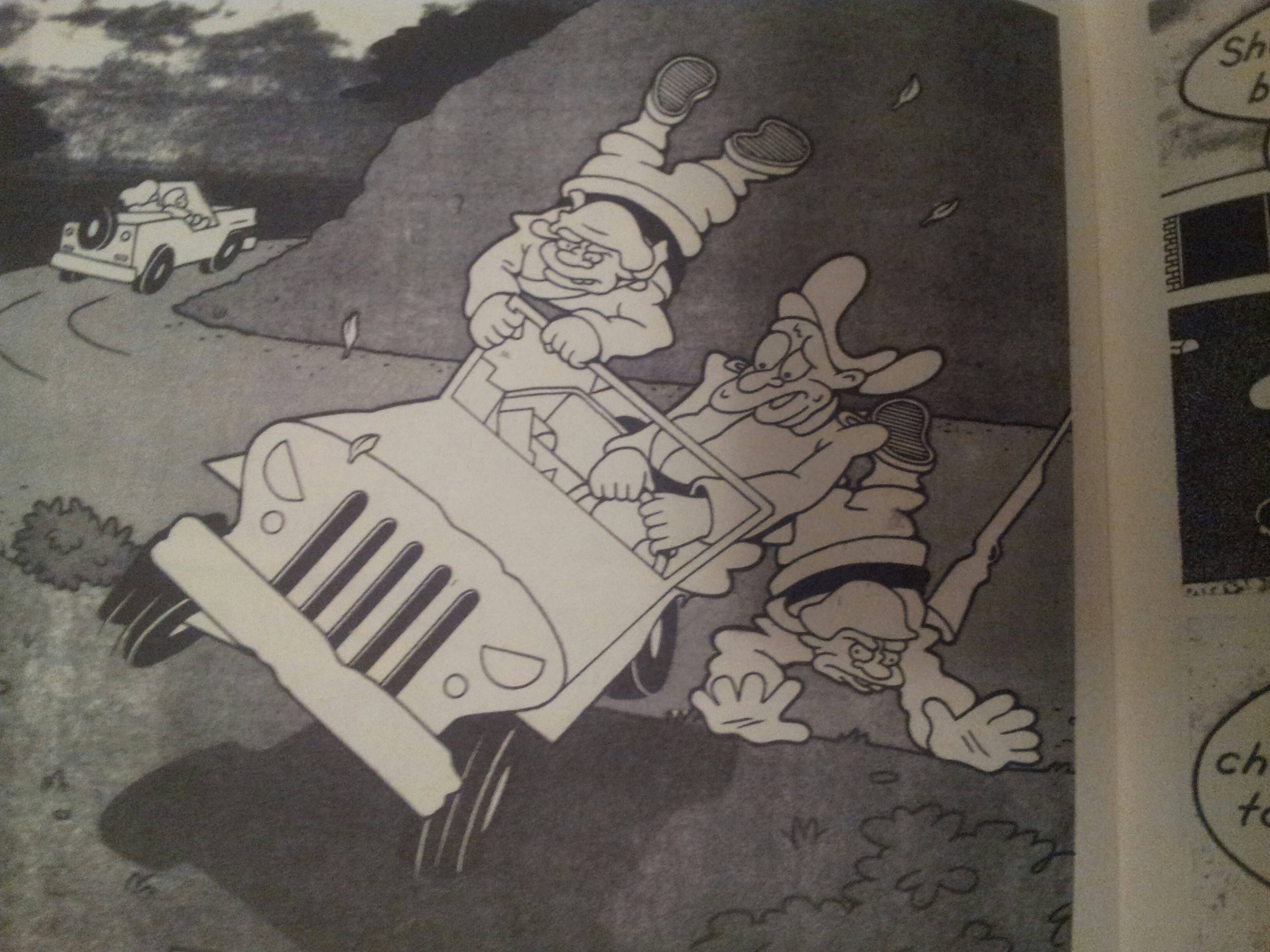

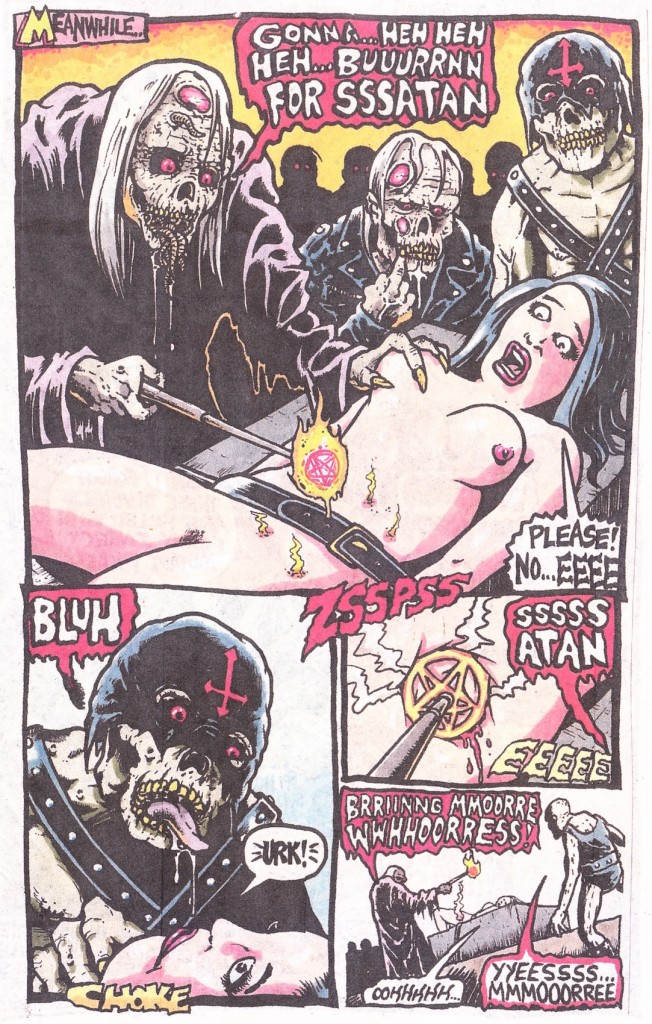

I imagine that something like that is what Phelps fears in the afterlife should gay marriage achieve equality. There’s no way that image or one like it should enter a theological discourse where it’s not taken as imbecilic. Yet, it seems that the primary opposition to Fukitor is that people are going to take it too seriously, that its macho-chauvinistic worldview isn’t sufficiently ludicrous to simply point at it and laugh. (Like a censor, the critic is, of course, quite capable of not being swayed by the dangerous message he perceives. The problem is, you know, other people who don’t possess the critic’s cultural analytic skills.) Some of the response over at TCJ reminded me of those critics of Paul Verhoeven’s Starship Troopers who pointed out the Nazi-like uniforms worn by its heroes as evidence for the film’s fascism. With a style that hardly could be called delicate or nuanced (or so I thought), he both delivered on the entertaining genocidal slaughter of a highly evolved alien insect species while pointing out that it was genocide we spectators were enjoying. Karns’ extremism is doing something similar: Fukitor’s diegeses take place within a particular sort of mindset — a souped up, more explicitly rendered version of 70s and 80s action film heroics and grindhouse terror. It finds enjoyment there in the same way one might be entertained by the xenophobic worldview of Chuck Norris’ Missing in Action series, but makes it all sufficiently extreme that only a true psychopath could ever find it a plausible expression of otherness. Here’s an example of heroic victory (against the Viet Cong) from the comic:

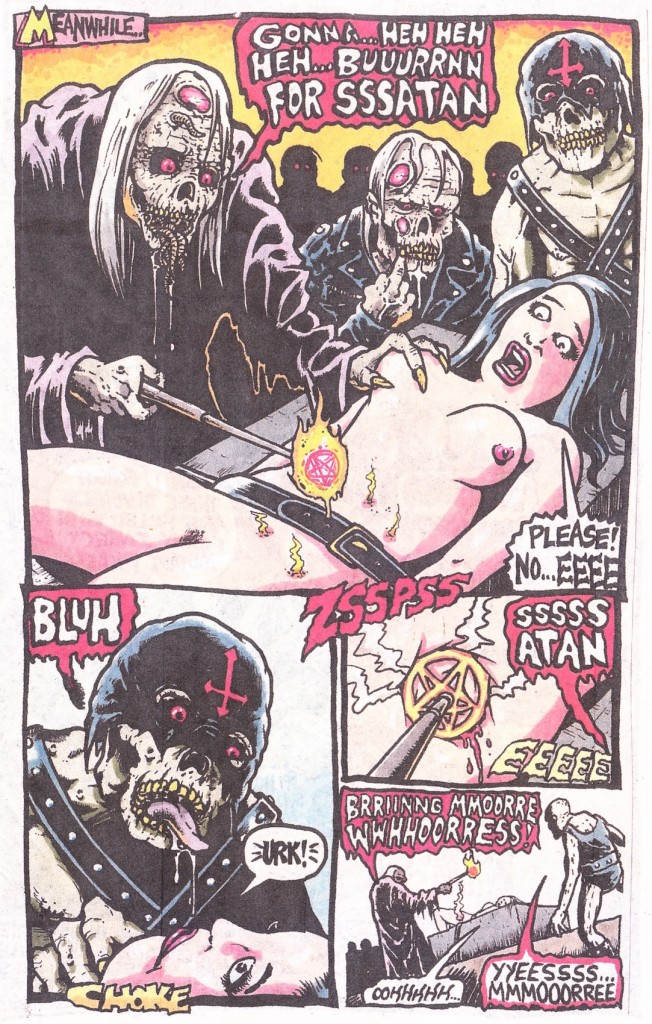

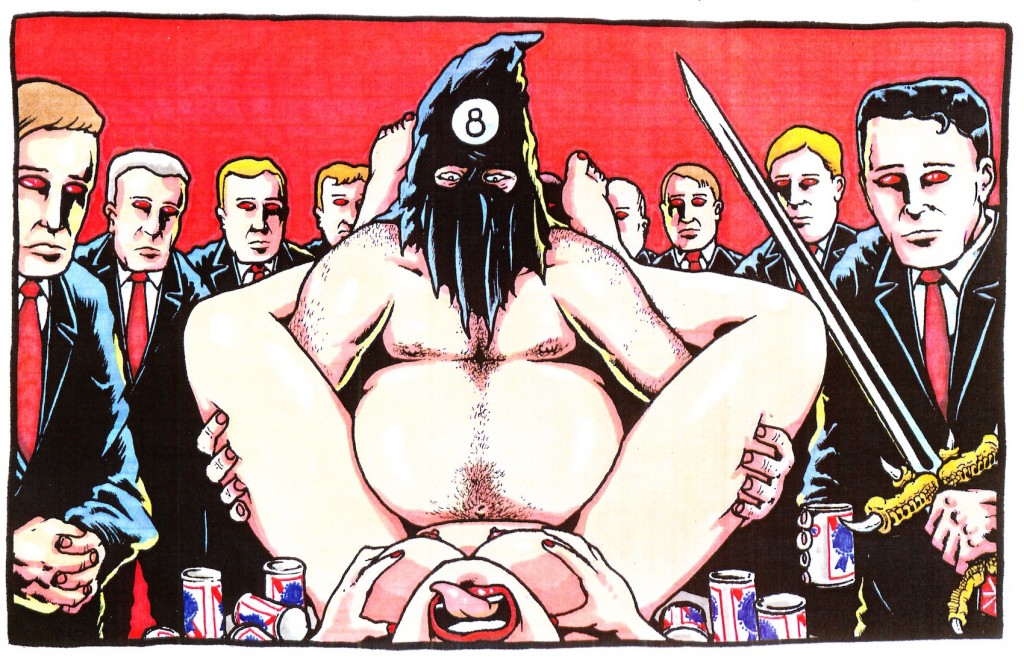

Fukitor 5, “The Green Hellion”

Having the hero become a cannibalistic war machine with one of “our boys” hiding in the back, meekly proclaiming victory with his fist raised in a feeble show of solidarity is enough to create something of a Brechtian distancing effect – at least, within me. That’s another way of saying I’m not merely going along with the literal views of the characters, nor is the story wanting me to. However, Darryl Ayo might still say (if he ever bothered to read the comic): “This isn’t subversive, this is the real thing. This is what racist caricature and hostility against nonwhites in the popular arts looks like. This is what racism looks like, served straight up.” What this fails to see is the caricature of white masculine power that pervades the comic. I can’t imagine even the staunchest white power patriarch wanting this comic to represent his worldview (just like the KKK has its rhetorical limits). Maybe Phelps is right, people need signs: “do not identify with hero,” “do not sympathize with the bigotry.” Thus, I’m going to supply some context for those who believe Fukitor entertains its ideal reader by simply presenting a shared worldview (as if this reader thinks the comic fairly presents his ideological take on existence).

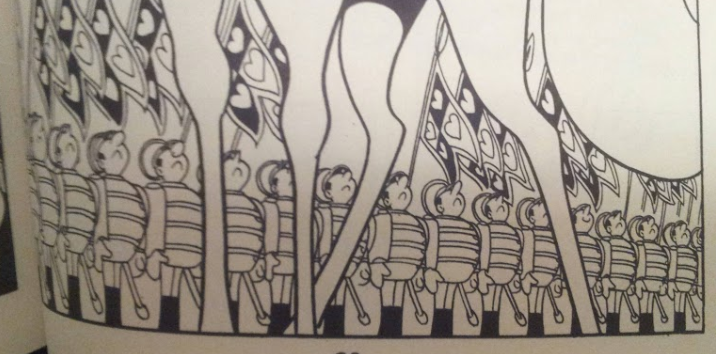

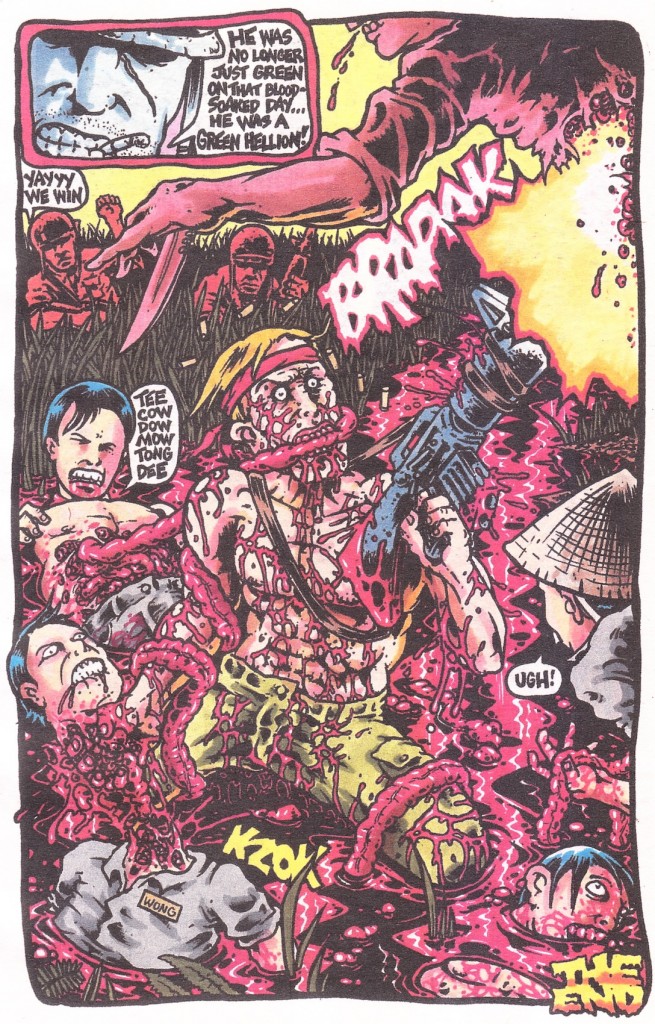

Much of the imagery in the three issues (5 through 7) that I purchased more easily serve radical feminism as misandrous stereotypes/parodies of patriarchal power than as actual reinforcement/mere reiterations of said power. Most of the examples for these stereotypes in what follows came from Judith Levine’s My Enemy, My Love. It occurred to me while reading some of that book around the same time as Fukitor that Karns shares or mocks (you decide) the same nightmarish fantasy that Andrea Dworkin, among others, has about masculinity: “Violence is male. The male is the penis; violence is the penis or the sperm ejaculated from it. What the penis can do it must do forcibly for a man to be a man.” [p. 138, Levine] Perhaps Karns’ most manifest take on this theme (if it’s possible) will be what he’s currently working on, a barbarian tale called “The Coming of Kok,” but from what I have in hand, look at this pinup scene from issue 5’s inside cover:

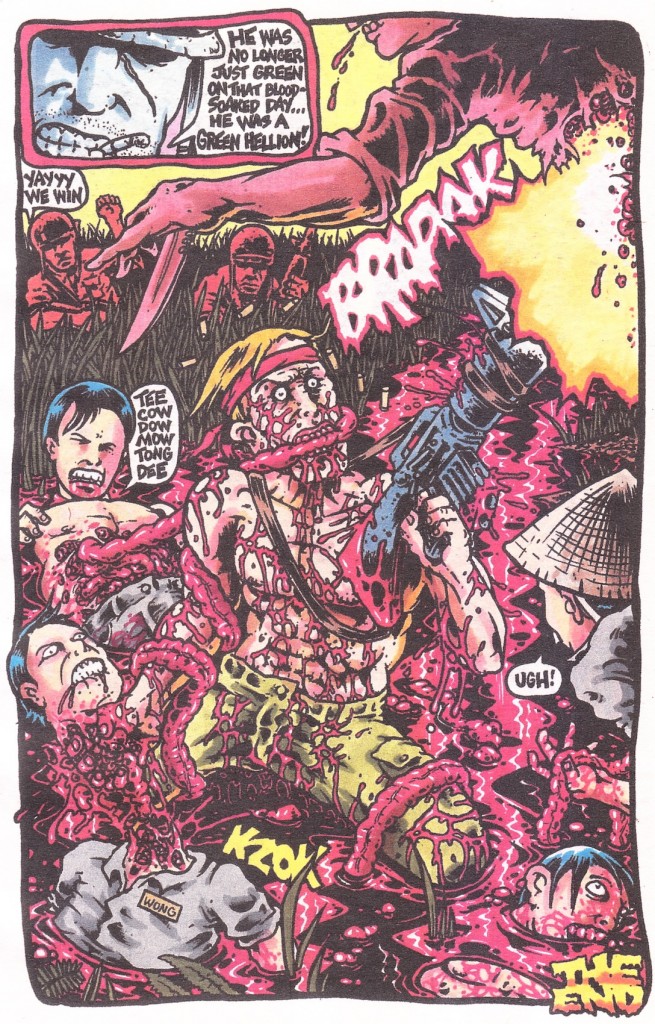

A demonic cabal (cf. red eyes) of white capitalists (note the business suits) is about to sacrifice a woman (with the ceremonial sword) after a masked executioner-type finishes sexually having his way with her. It’s hardly reading between the lines to find affinity between this drawing and the radically feminist conflation of capitalism and patriarchy: “to attack male supremacy […] consistently, inevitably means attacking capitalism […]” and “when you talk women’s liberation you inherently talk anti-capitalism and anti-private property.” [p. 78-9, Echols; first statement is from Redstockings’ co-founder Ellen Willis, the second from an unknown speaker at the 1968 Sandy Springs conference] Levine suggests this analysis understandably leads to misandry: “[M]an-hating remains not an action but a reaction, not a power but a subversion of power. In a patriarchal world, woman-hating is built into every institution. […] If misogyny is the Establishment, man-hating is no more than a counterculture.” [p. 18] She analyzes three overarching stereotypical categories of misandrous imagery (Infant, Betrayer and Beast), but the one that Fukitor deals in, almost exclusively, is the Beast: “Images of [which] confront the male body, its attractions and its threats. While [its subtypes] the Prick and the Pet indicate a raised eyebrow (and a raised skirt) toward “animality,” the Brute and the Killer embody women’s detestation and terror of male violence.” [p. 27]

The Brute is represented by that big, fat, white trash dude in quasi-Klan gear who’s just polished off a lot of Bud before going to town on his victim. Levine describes this subtype as “the ogre under that bridge, and his weapon is real: rape. Representing predatory, rapacious, implacable, and misogynistic sexuality, the Brute embodies what every man could do to every woman, and crucial to his efficacy as a terrorist is his penchant for disguise.” [p. 136] Those men surrounding the Brute represent another subtype, the Killer. This guy is the technocrat who avoids empathy in favor of realpolitiks, i.e., downplaying feminine characteristics in favor of masculine ones. Violence is always an abstraction, a matter of rationality. It’s as if Karns used this stuff for a script: Capitalists, not wanting to get their hands dirty, are using a loutish workingman — plying him with cheap beer — to rape a woman in service of their plutocracy. In other words, capitalism rests on a big fat underbelly of structural violence (violence that’s written into the system), and that violence is rape. If you’ve spent any time reading feminist critiques of pop culture on the web, you’ll know that the term for this emboldened allegorical message is ‘rape culture.’ Quoting Susan Brownmiller, Levine notes how sexual violence is conjoined with keeping the peace: “Man’s discovery that his genitalia could serve as a weapon to prehistoric times, along with the use of fire and the first crude stone axe. From prehistoric times to the present, I believe, rape has played a critical function. It is nothing more or less than a conscious process of intimidation by which all men keep all women in a state of fear.”

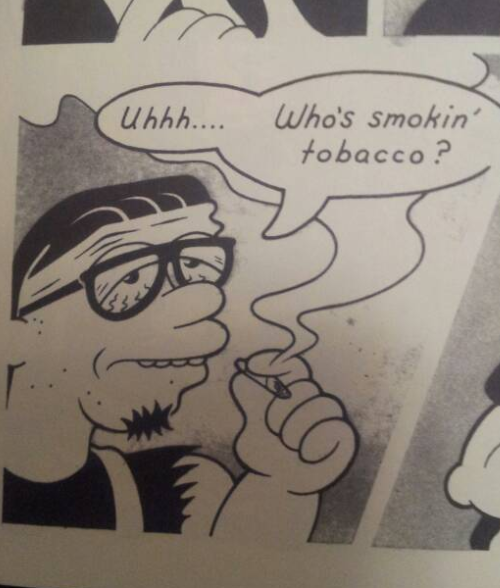

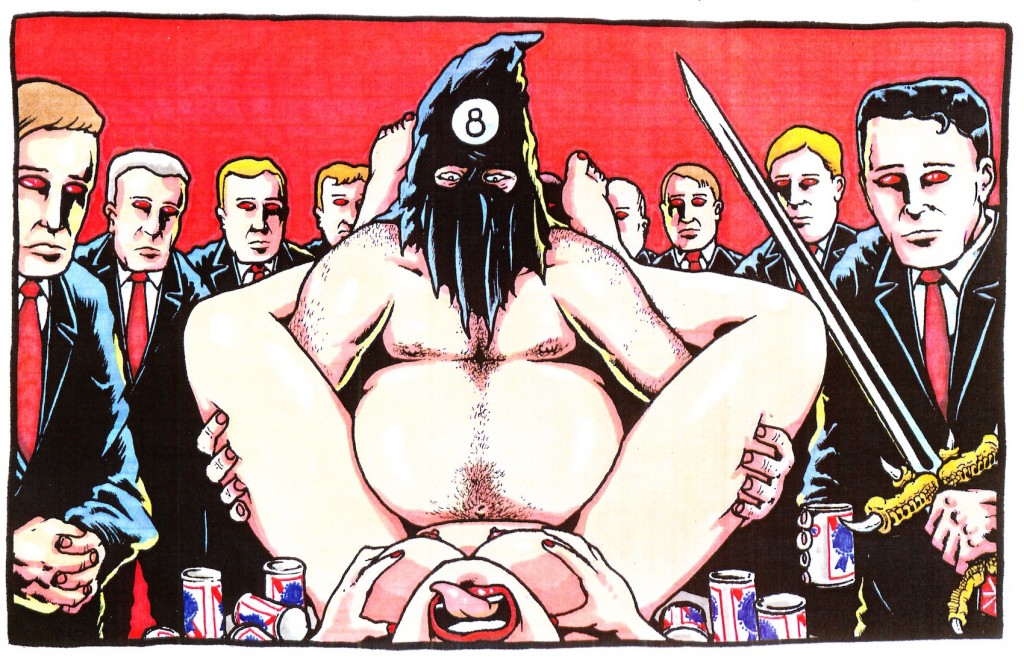

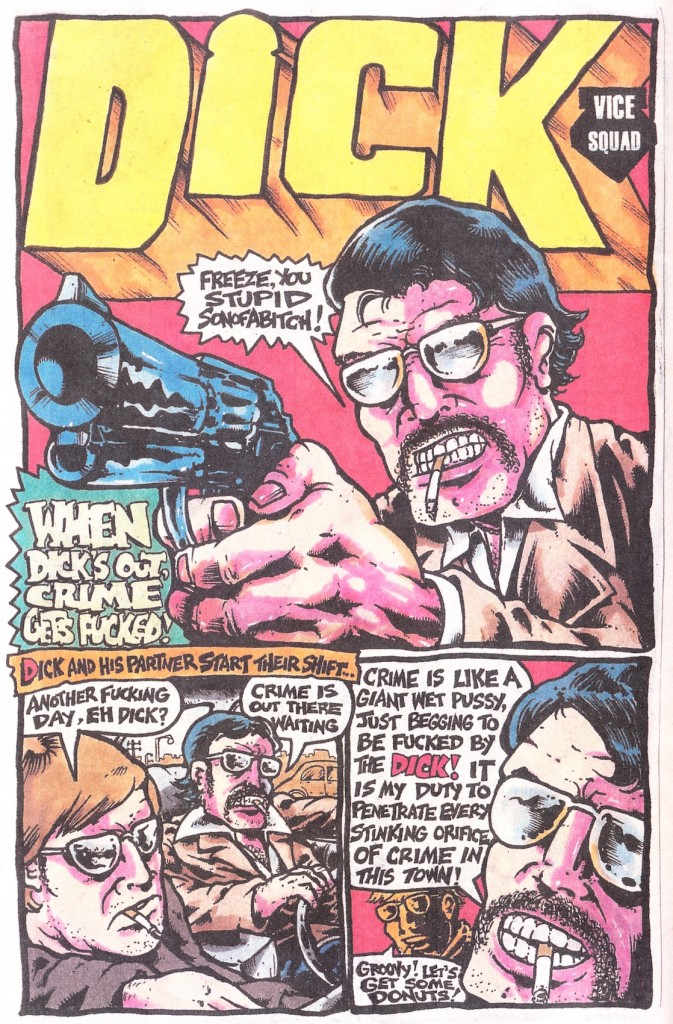

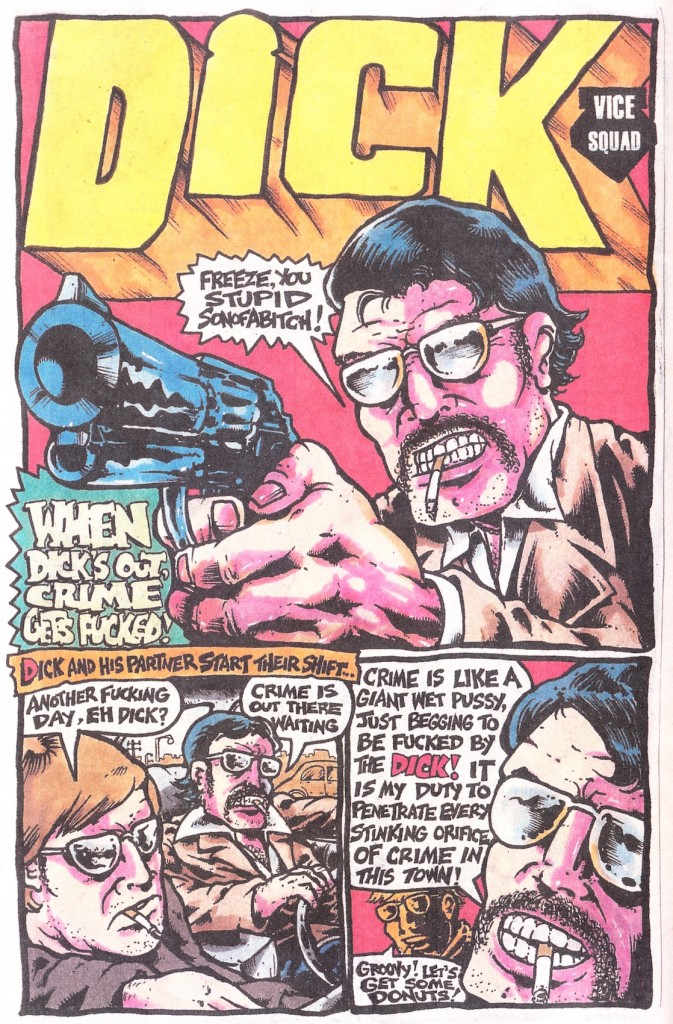

From Fukitor 6, “Dick: Vice Squad”

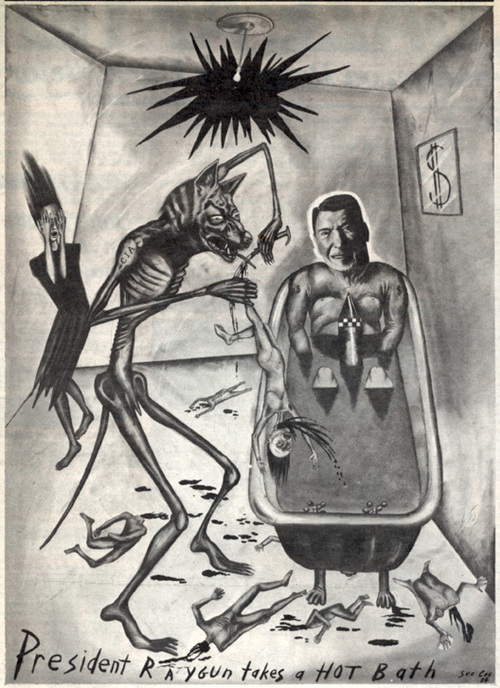

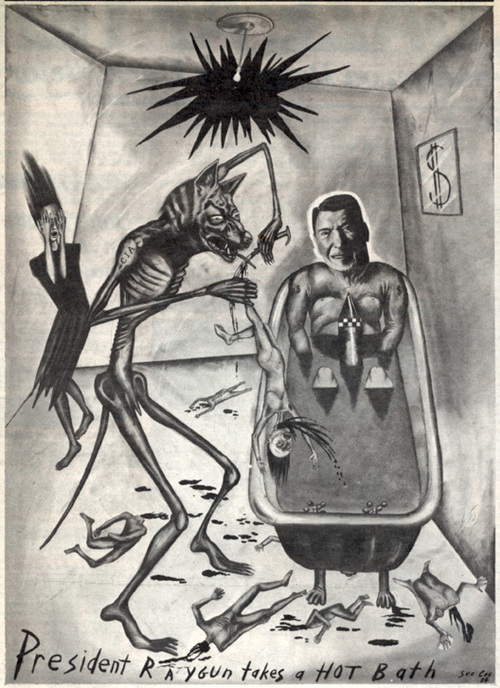

Phallogocentric laws require like-minded law enforcement, and Detective Dick is rape culture’s perfect policeman — a renegade who won’t go soft on crime, which is analogized to womanhood. He is also an example of another subtype, the appropriately titled Prick. He is “imperious, self-centered and self-satisfied, puffed up and truculent.” Dick’s the walking embodiment of the phallus, i.e., “masculine authority, power, patriarchal law and language; [depending] for its reputation on not being seen.” [p. 160] His eyes are behind shades, so he can see you, while you can’t exactly return his look. According to Laura Mulvey, the stereotypically masculine role is to do the defining, the feminine is to be defined: “In a world ordered by sexual imbalance, pleasure in looking has been split between active/male and passive/female. The determining male gaze projects its phantasy on to the female form which is styled accordingly.” To reverse the gaze, to see through those shades, is to possibly see the phallus as a flaccid, impotent penis (smaller than you think, like the man behind the curtain in Oz). Thus, “[a]ccording to the principles of the ruling ideology and the psychical structures that back it up, the male figure cannot bear the burden of sexual objectification.” The Prick has to keep up appearances of being hard. One way of doing this is pretty common throughout Fukitor, such as in the present example or the “Green Hellion” page above, namely use a weapon as the phallus, making violence the signifier of hardness, of masculinity. I don’t much see a difference in Karns’ treatment and the feminist message of, for example, Sue Cole’s “President Raygun Takes a Hot Bath”:

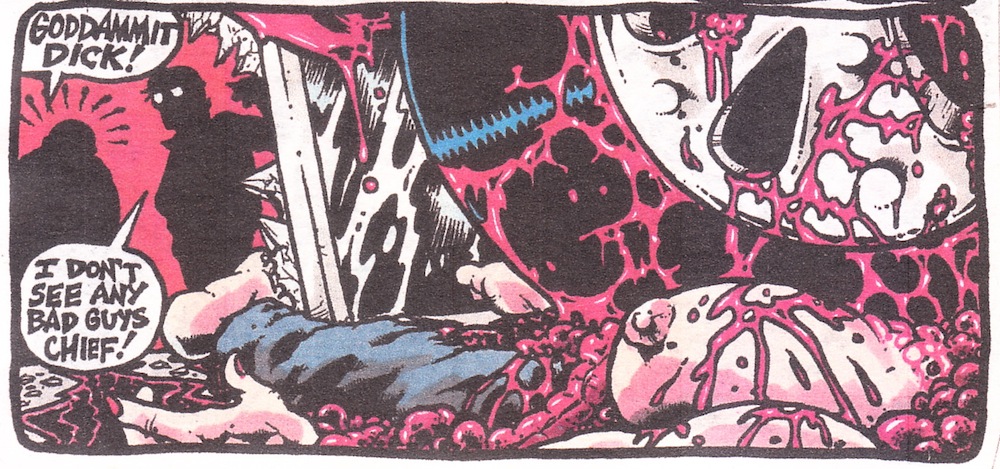

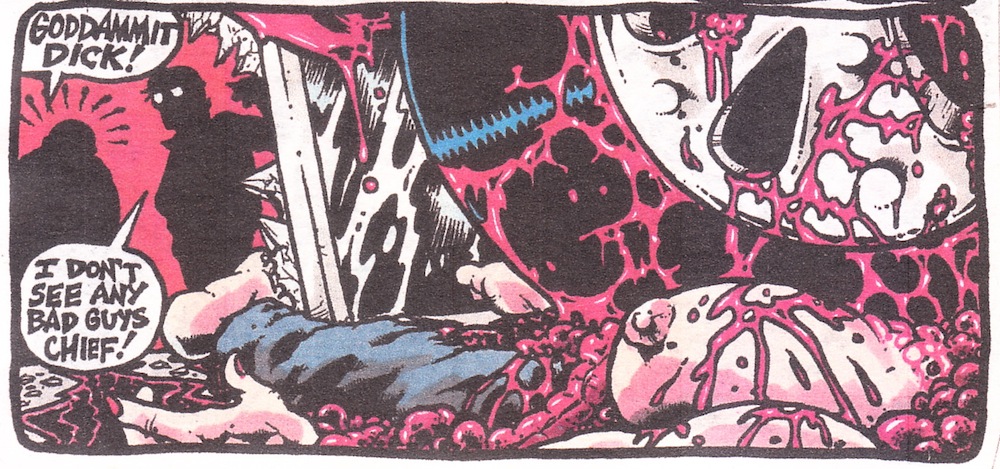

Both take pleasure through humorous depiction of overcompensating macho violence. In showing the Prick for what he is, “humor is the great deflator.” [p. 165] The message behind “Dick: Vice Squad” cannot reasonably be equated with Dirty Harry’s expressed anxiety towards San Francisco’s feminized, liberal bureaucracy when the hero’s success at dealing with hostage situations tends to look like this:

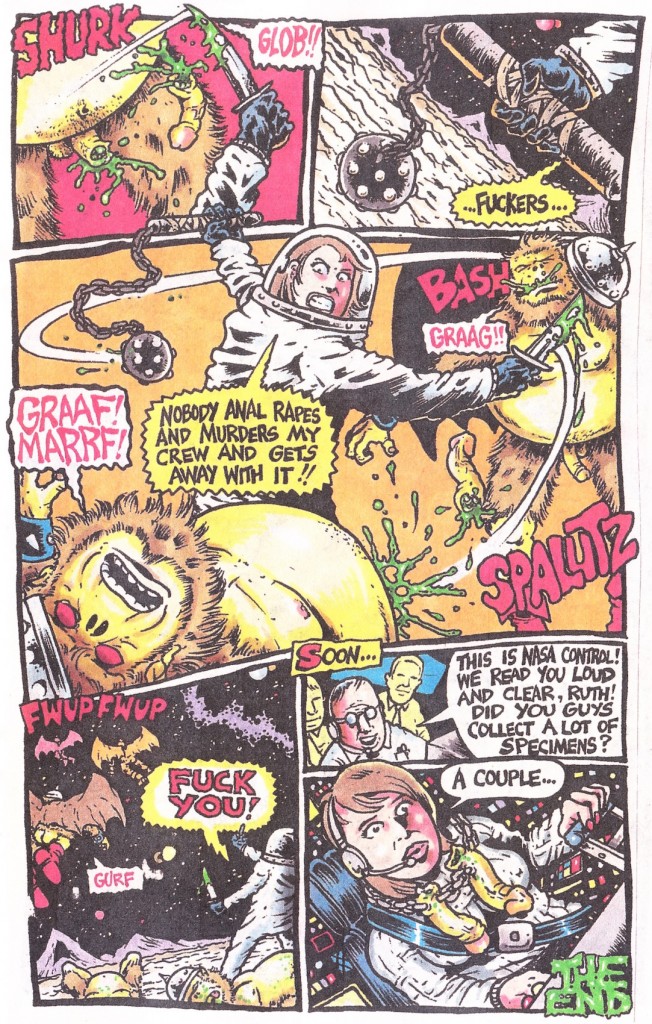

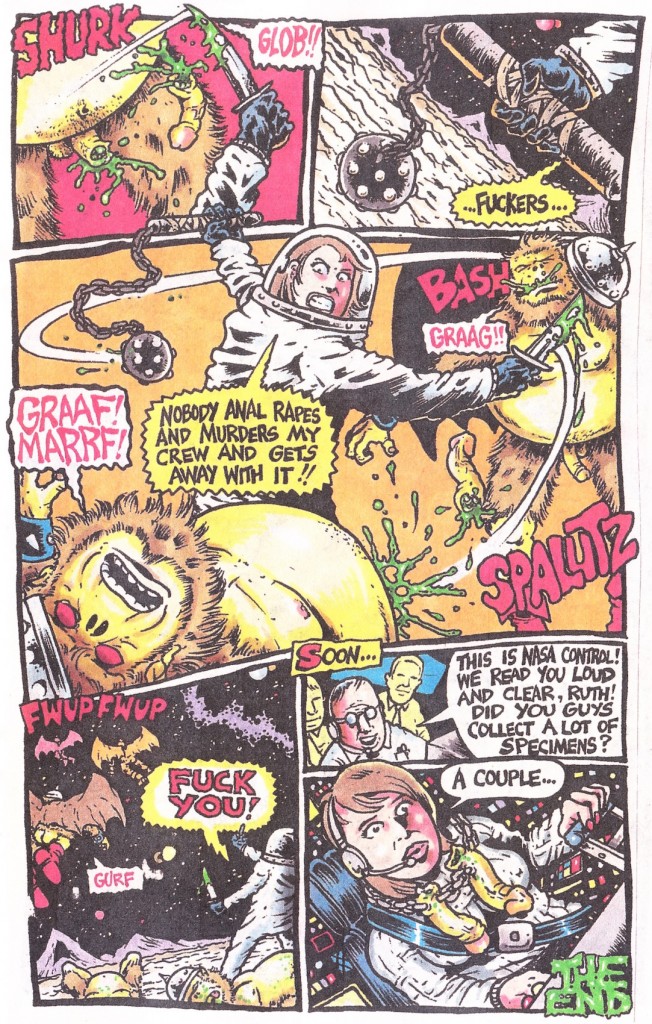

In the same issue, Karns satirizes another prominent area of phallogocentric domination, the objective world of science. Rather than the image of a rationally disinterested observer that feminists such as Luce Irigaray have questioned, the scientific explorers of “Buttraping Bat-Apes on Pluto” are bullheaded and driven by petty jealousy and selfishness:

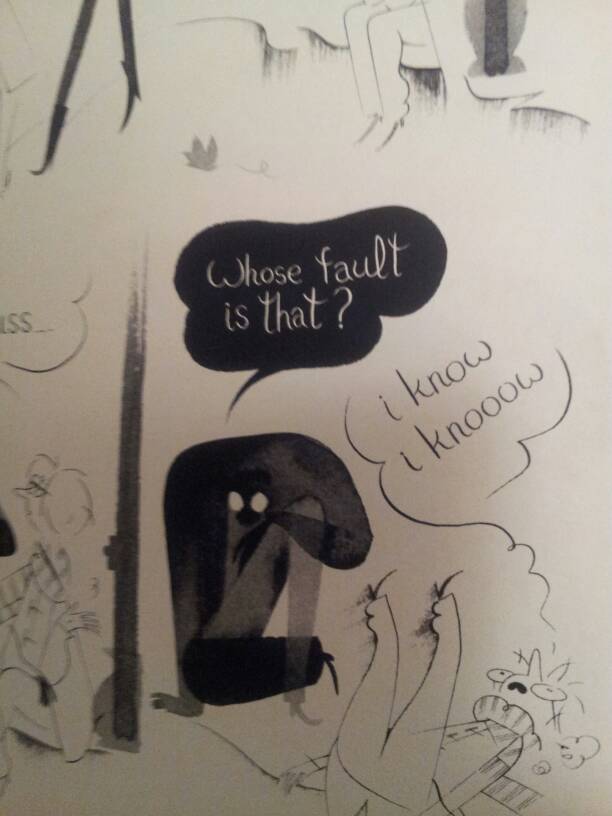

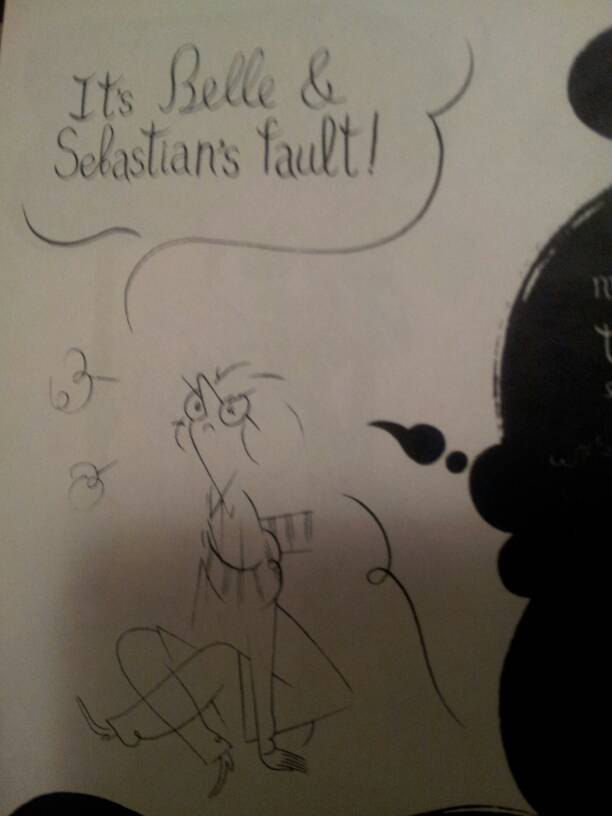

Being petulant children, they require a mothering figure. Instead of the Beast, these fellows fit the stereotype of the Mama’s Boy (a member of the Infant class). Levine describes it as, “women trade stories of manipulating and being manipulated by, doing for and being done in by their big male bundles of needs, demands, and expectations. Yet women are exasperatingly eager to take the rap for these bad boys: if men are babies, guess whose fault it is?” [p. 32] The men, because of their cocksure nature and obstinate refusal to listen to the woman, are systematically dismantled in the fashion suggested by the story’s title. But she has her day, avenging her fallen colleagues:

Thus, the woman becomes the hero only after slaughtering the butt-raping primates, chaining the masculine spoils around her neck. This image is a more comically violent interpretation of Martha Nochimson’s feminist critique of Kathryn Bigelow’s meteoric rise in Hollywood power circles with Hurt Locker. Referring to her as the “transvestite of directors,” Nochimson wrote, “[l]ooks to me like she’s masquerading as the baddest boy on the block to win the respect of an industry still so hobbled by gender-specific tunnel vision that it has trouble admiring anything but filmmaking soaked in a reduced notion of masculinity.” The director, like the female scientist, appropriates phallic power by dressing herself in it. Although Karns isn’t necessarily criticizing his character’s actions.

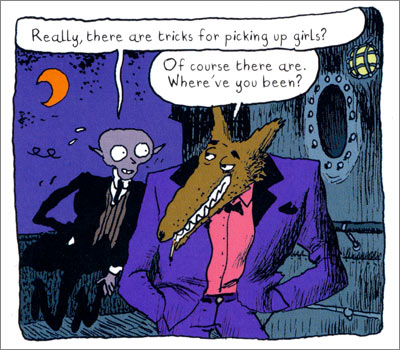

I could keep going with examples (such as Karns’ twist on the James Bond spy as a werewolf, a swaggering poonhound that he reduces – recalling Twilight‘s Jacob — to a lapdog), but that’s enough. Either the reader will buy it at this point or never will. A comic that can be read so effortlessly as radical feminist stereotypes of masculinity in pop culture suggests something other than a straightforward support of white male privilege. If Karns had done all this in prose form, it would read something like talking points from Valerie Solanas’ hilarious SCUM Manifesto:

The male is completely egocentric, trapped inside himself, incapable of empathizing or identifying with others, or love, friendship, affection of tenderness. […] His responses are entirely visceral, not cerebral; his intelligence is a mere tool in the services of his drives and needs; he is incapable of mental passion, mental interaction; he can’t relate to anything other than his own physical sensations. […] He is trapped in a twilight zone halfway between humans and apes, and is far worse off than the apes because, unlike the apes, he is capable of a large array of negative feelings — hate, jealousy, contempt, disgust, guilt, shame, doubt — and moreover, he is aware of what he is and what he isn’t. […] To call a man an animal is to flatter him; he’s a machine, a walking dildo. It’s often said that men use women. Use them for what? Surely not pleasure. […]

His greatest need is to be guided, sheltered, protected and admired by Mama (men expect women to adore what men shrink from in horror — themselves) and, being completely physical, he yearns to spend his time (that’s not spent `out in the world’ grimly defending against his passivity) wallowing in basic animal activities — eating, sleeping, shitting, relaxing and being soothed by Mama. Passive, rattle-headed Daddy’s Girl, ever eager for approval, for a pat on the head, for the `respect’ if any passing piece of garbage, is easily reduced to Mama, mindless ministrator to physical needs, soother of the weary, apey brow, booster of the tiny ego, appreciator of the contemptible, a hot water bottle with tits.

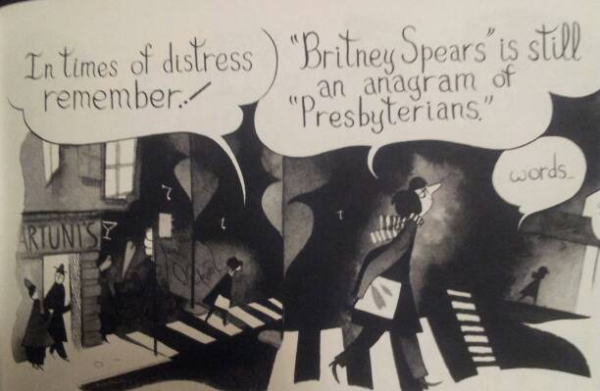

Fukitor takes enough pleasure in puncturing and dicing up men, mocking and castrating phallic power, to qualify as an auxiliary work in service to the Society for Cutting Up Men: “[T]he Men’s Auxiliary are those men who are working diligently to eliminate themselves, men who, regardless of their motives, do good, men who are playing ball with SCUM.” One doesn’t have to agree with the message being delivered to find something enjoyable or worthwhile here. Regarding Solanas’ appeal to some feminists, Levine writes, ”a kind of lunatic nihilism helped burn over the old assumptions, clearing space for constructive revolutionary ideas.” Quoting Vivian Gornick: “The first time a woman said, ‘Cut it off!’ it was great. You never dreamed for a minute she meant it. It was the announcing: we are no longer afraid to say the unsayable.” [p. 216] Appreciating Solanas doesn’t make a woman into the nightmare a Men’s Rights Advocate has every time he hears a Loreena Bobbitt joke. Likewise, enjoying Fukitor doesn’t commit one to supporting whatever views that are expressed therein. As alluded to above, it’s a fairly simplistic view of how belief systems work in the minds of racists, gun rights advocates, chauvinists, paleoconservatives, the pro-war contingent, or whomever else might be represented within Karns’ aesthetic to believe he’s merely giving voice to how they feel about themselves. Nevertheless, even if one takes the comic as a straightforward depiction of a troubled psyche’s bigoted worldview rather than (as I’ve been arguing) the intentional use of such a worldview for comical purposes, one could still laugh at it by treating it as if it’s as worthy of serious reflection as one of Phelps’ signs.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

References:

Echols, Alice (1989) Daring to Be Bad: Radical Feminism in America, 1967-1975. University of Minnesota Press.

Levine, Judith (1992) My Enemy, My Love: Man-hating and Ambivalence in Women’s Lives. Doubleday.