I was originally not going to write a conclusion for last week’s Komikusu discussion. But then I was chatting to Tucker Stone, and he mentioned that he’d enjoyed reading the roundtable.

This took me a little aback, because Tucker’s come out fairly strongly in the past against the “we must read more lit comics!” meme as it applies to Western comics. In an interview with Tom Spurgeon, for example, Tucker said:

There’s a temptation to label mainstream fans as being lazy for not caring about Swallow Me Whole or Blankets, to call them “bone-ignorant” — that’s just a bunch of horseshit. It’s an attempt by boring assholes to assign an overall meaning to a bunch of personal choices made by a group of people that those boring assholes don’t know anything about. On an individual level, I’ve heard a couple of people say they don’t want to read comics that focus on the mundanities of regular life, but I’m more often exposed to people who just like what they like because it’s what they fucking like.

I actually agree with that. Yet, at the same time, I’d like to see some more interesting manga titles succeed in the U.S. So…what’s my problem? Why does the push for more interesting comics make me itch in a Western context and not in a manga one?

Perhaps the answer is simply that I’m inconsistent. But, appealing as that solution is, I think there’s actually something else going on. Specifically, the way the debate is framed in a Western context tends to be different than the way the folks on this roundtable framed it. As an example, here’s Sean T. Collins discussing his wish that there was more discussion of western lit comics in the blogosphere.

I’ll tell you what my big question is: Why do superheroes dominate the online conversation the way they do? Last week saw the release of Jim Woodring’s Weathercraft and Tim Hensley’s Wally Gropius, two gorgeous and weird books that truly make use of the stuff of comics and contain the kind of material you can mentally gnaw on for days on end, but I guarantee you that no matter which comics blogs you read, you read more about Paul Levitz’s return to the Legion of Superheroes. And chances are good that if you’ve read about Daniel Clowes’s Wilson, what you read prominently featured that page where the character makes fun of The Dark Knight. What gives? If you want to make the argument that sheer numbers justify the choice of what bloggers and comics sites cover, I suppose that’s your prerogative. And don’t get me wrong — I read and enjoy multiple superhero comics every single week, and have lots to say about a lot of them. I also understand the need to make a living, which in Internet terms means unique pageviews.

But so much of the comics Internet consists of individual or group blogs where, presumably, there’s no editorial mandate to maximize hits. Indeed, the major selling point of the blogosphere is its lack of the traditional gatekeepers and incentive structures that bedevil mainstream journalism. Meanwhile, even the big group blogs owned by major communications corporations tend to be personality-driven, reflecting the interests and styles of their writers to a refreshing degree — and those writers tend to be interested in all sorts of comics, in their spare time at least. So yes, the nature of the coverage is often idiosyncratic, which is great. But why is that the comics being covered differ so little from what you’d read about on Marvel.com or The Source? Should those of us in the position to do so make an effort to broaden the scope of what we’re presenting to our readers as the comics worth buying, reading, and talking about?

And here’s Kate Dacey responding to Sean in that comments thread.

There’s a similar divide in the mangasphere as well: a lot of sites focus on mainstream shonen and shojo titles (the manga equivalent to tights and capes, I guess) while neglecting the quirkier stuff. To be sure, there are many sites that cover the full spectrum of titles, or focus on a niche, but the pressure to stay current with new releases and draw traffic discourages a lot of folks from waxing poetic about the stuff at the fringes. Looking at my own site stats, for example, a review of Black Bird or My Girlfriend’s A Geek will attract a much bigger readership than, say, The Times of Botchan.

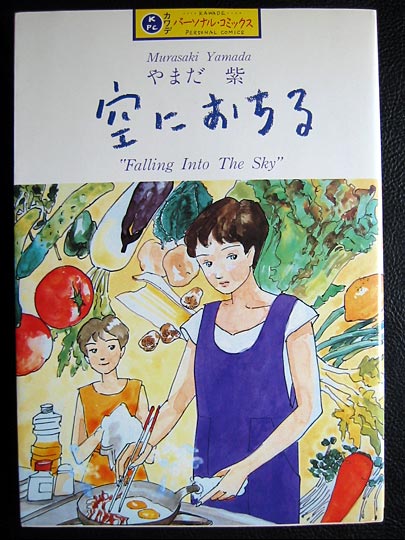

Which brings me to the argument I’d like to see explored somewhere: how do we interest older readers in manga that’s written just for them? What kind of marketing support would, say, the VIZ Signature line need in order for some of those titles to crack the Bookscan Top 750 Graphic Novel list? Are there genres or artists we should be licensing for this readership, but aren’t?

Kate’s post there is what inspired me to organize this roundtable. And obviously there are close analogies between what she’s saying and what Sean is saying. But I think there are important differences as well. Mainly — Sean makes the dissemination of lit comics into a moral issue. “Should those of us in the position to do so make an effort to broaden the scope of what we’re presenting to our readers as the comics worth buying, reading, and talking about?” he asks, and the answer is obviously that yes, we should. The problem for Sean is that super-hero comics are taking up too much space because the people in the blogosphere aren’t doing their job in educating their readers about better fare.

Kate starts from the same place — how do we get more better manga out there? But she doesn’t bother with the moral question at all; instead she goes right to logistics. Not “you people should be doing more!” but, “presuming there are people who would like to read different kinds of manga out there, how do you reach them?”

Kate’s pragmatic approach was absolutely the one adopted by the roundtable. Erica Friedman tried to figure out how scanlations could be used legitimately to make more and different kinds of niche mangas available. Brigid Alverson, Deb Aoki and Kate herself talked about practical marketing steps that could be taken to reach new audiences. Peggy Burns pointed out some strategies that have worked for Drawn and Quarterly in the past. Ryan Sands and Ed Chavez tried to map out the historical lay of the land, explaining how manga has been categorized and sold in different ways at different times in both the U.S. and Japan. And Shaenon Garrity offered some more possible solutions, while also pointing out some possible pitfalls.

If you read through these pieces, though, what’s almost as noticeable as what is said is what isn’t. Nobody in the roundtable says that the problem is that readers’ tastes suck. Nobody says the problem is that bloggers aren’t doing enough to promote the right kind of manga. Both Shaenon and Deb mention Naruto in a “yep, the manga we’re talking about aren’t going to sell like that” kind of way — but they don’t seem resentful of Naruto’s success, the way Sean Collins seems resentful of superheroes (despite the fact that he reads them himself). In fact, unless I’m missing something, nobody in the roundtable says anything mean about mainstream, successful genre manga at all.

And why should they? The success of mainstream genre manga doesn’t hurt sales of To Terra or A Drifting Life or Travel or what have you. Because, as everybody in the roundtable seems to realize, the people who are buying Naruto — they aren’t the audience for Emma or Tramps Like Us. Not that nobody could possibly read or like all of those series, but simply that the demographic is different. If you want to increase sales of Oishinbo, the way you do that is not to go after readers of Gantz. The way to do it, as Shaenon says, is to get it into cooking stores.

Lit comics have had a lot of success in the U.S. precisely by finding different audiences. But the comics scene here is still so small, and still so defensive, that its vision still seems to be defined to a surprising degree by the mainstream. It’s not just Sean by any means — super-hero crap is, in general, seen as not just bad, but oppressive. There’s only room for so many comics, and the bad forces out the good. It therefore becomes every intellectuals duty to battle against the filth.

I don’t know that the manga scene in the U.S. is bigger than the Western comics scene. But it’s more demographically diverse, and it always has before it a pretty compelling vision of a possible world in which there are no mainstream comics, because comics themselves are mainstream. As a result, manga critics seem to have figured out what Western comics critics still have some trouble with. Namely, improved morals don’t sell comics; better marketing does.

Of course, just because manga folks have figured this out doesn’t mean that there will ever be more awesome manga available on these shores. But it seems like a good first step.

____________

The entire Komikusu roundtable is here.