Suat notes acidly that any discussion of Swamp Thing is likely to be mired in nostalgia. I think we’ve actually got a couple of folks on the roundtable reading them for the first time…but Suat’s certainly got me pegged. In high school, I read and reread and rereread all the issues of Alan Moore’s run on more times than I can probably count. However, when we went off to college, it was my brother who got most of the issues (I got Watchmen) and, since I knew them so well already, I never did get the trades. As a result, it’s probably been 15 years since I’ve read last part of Moore’s run; issues #57 to #64, from way back in 1987.

So…contra Suat, are they as good as I remember? Well…no and yes. It’s certainly true that, as Suat suggests, they’re, massively, massively overwritten. I think as a kid I just skipped over most of the giant glaring gobs of text boxes. As an adult I’m more conscientious, or stupid, or some combination of both, and I actually tried to read them all — and, yeah, that really doesn’t benefit anyone. I think the interminable, tortuous extended metaphor comparing the emergency care ward of a hospital to a forest is probably the absolute low point of this volume— “in casualty reception, poppies grow upon gauze, first blooms of a catastrophic spring…a chloroform-scented breeze moves through the formaldehyde trees…” yeah, yeah, we get it already, you’re a poet, now would you mind shutting the fuck up?

The painful thing is that one or two of the images might actually work — “his body’s the grave of his mind” is nice; the idea of the EEG screen as “steep green hills”. But Moore’s entranced with the fertility of his own pomp; why stop with one sharp image when you can carry the thing through from too much to toweringly tedious to self-parodic and beyond. Moore’s road to hell is paved, not with good intentions, but with loose-bowelled facility. Rereading this, it becomes clear that Promethea’s self-absorbed cleverness isn’t a decadent falling off, but an unfortunate potential that Moore indulged, to some extent, throughout his career.

Still…Moore’s language certainly has an upside as well. He lets his sentences take over and run amok because he loves them; his self-indulgence is really in a lot of ways an indulgence of words, which he likes to stroke, and cuddle and giggle with in the back of the car seat. The first (two-part) story in this volume, for example, opens with a pound and a half of completely gratuitous Aussie dialogue, tossed in, it feels like, just because Moore couldn’t resist once the idea had popped into his head.

“bleedin’ peroxie pooftah” “ponder on the porcelain” — that’s enough goofy alliteration to make Bob Haney blush.

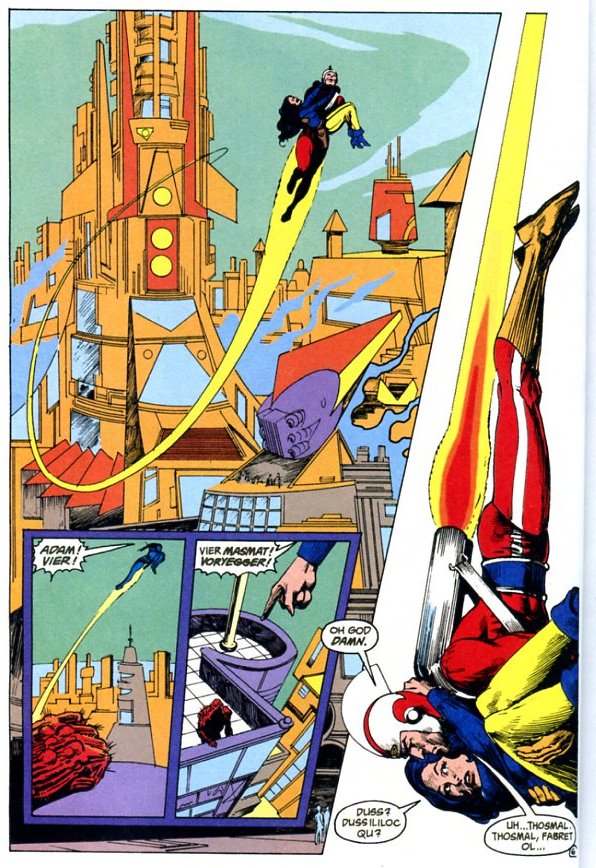

Once he gets started, of course, Moore just can’t stop…which is why, a couple of pages later, he just goes ahead and literally invents his own language:

When you first look at this, it feels like a tour de force. Moore doesn’t just throw in a few words of dialogue; he keeps going for page after page in a consistent, invented language. You can understand just enough of it to tell that the language does work; Moore actually knows what these people are saying — and you could figure it out too, if you had just a little more information.

That’s Adam Strange talking to his wife Alanna. For those not in the know, these are both old, old dc space opera characters. Adam Strange is this random earth guy who gets hit by a “zeta beam” which transfers him across billions of light years to Rann, where he becomes a hero. But the beam wears off over time, so he’s always getting dumped back on earth, and having to run all over the planet to find the next zeta beam (they come with some frequency) to zap him off to the stars again.

Anyway, in Moore’s story Adam knocked up against swamp thing (whose consciousness has been forced off earth — long story) in the zeta beam and was injured, and has now recovered. That’s where we are with the panel above. And after a reread or two, you can translate that first sentence at least; Alanna is saying, “Adam, what happened?” And Adam I think answers, “Uh…I’m not sure exactly what happened,” or something like that. I especially like the “Uh…” there — I think Adam is pausing in order to shift into thinking in another language — these are the first words he’s spoken that aren’t in English (he says his wife’s name a couple panels up, but that doesn’t really count.)

So, again, the effect initially is dazzling. But…think about it a second, and the whole thing seems more than a little ridiculous. This isn’t Tolkein spending a lifetime or thereabouts creating another tongue. This is Alan Moore pulling a language out of his ass…and that’s exactly what it looks like. It’s not Japanese, !Kung speech, or even German. Really, it’s not another language at all; barely more alien than the Aussie dialect we started with. It’s really just a kind of code. Moore seems to have written out his text and then substituted made-up words on a more or less one to one basis. In some sense, even more embarrassing than just having all your spacepeople talk English. Why try at all if you’re going to do a half-assed job?

And the answer to that, as Moore shows, is that sometimes, if the job is big enough, or original enough, or cool enough, it is in fact worth doing a half-assed job just to see where you end up. The language is nonsense — but then, this is a pulp space story, which means the whole thing is nonesense. After all, we’re in the middle of trackless space; why on earth (as it were) does everybody look human?

Besides, and what is the main point, having these silly out-of-place humans speak in silly out-of-place code allows Moore to do some things that he couldn’t have gotten any other way.

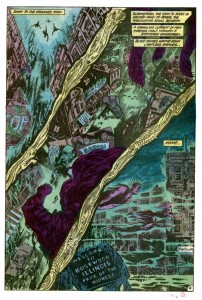

I think this page just brilliantly evokes the strangeness…not of another world or planet, necessarily, but of being far away, in a different culture. The best touch is that, after a couple panels of alien speech, Moore has Adam speak in English. Because at first you’re trying to figure out the alien dialogue, the moment when Adam talks “normal” comes as a small shock. For a second you get to see him, oddly, as the alien, the one out of place. It reminds me of a scene in C.S. Lewis’ space trilogy where Ransome, after spending some months with aliens, sees a bizarre creature and then a second later realizes that it’s himself in a mirror — he’s had the “privilege” (I think he uses that word) of seeing himself as the Malacandrians see him.

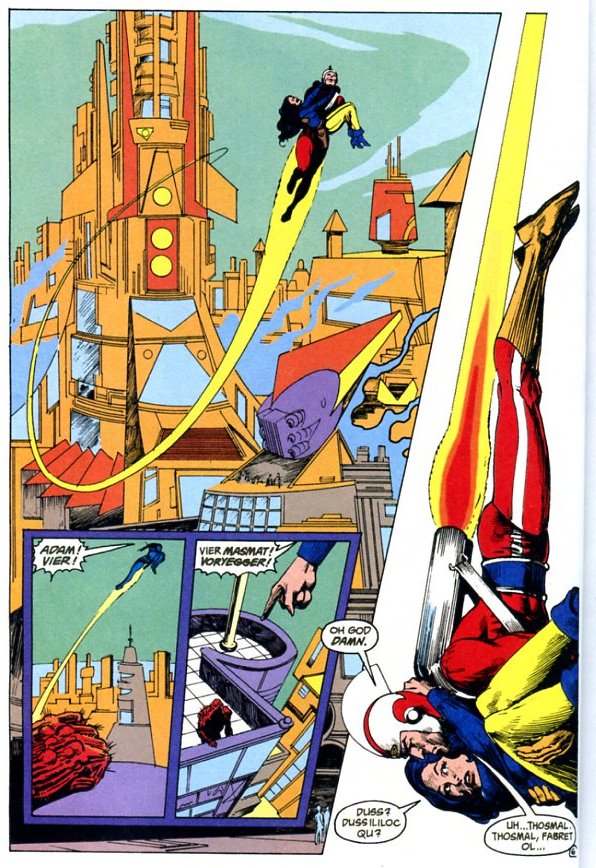

The way Moore uses his “language” in the sequence below is great too:

Again, the juxtaposition of the Rannian and English is basically the whole point of the page. “You speak English!” “So..do…you.” It’s such a hyperbolic ex-pat moment…and again, there’s that weird disjunction as you go from trying to follow the Rannian dialogue to realizing that everybody is suddenly speaking English. And then Moore switches the character’s positions, as Adam and Swamp Thing talk to each other, and Alanna is the odd one out:

I find that whole bit really charming. In the first place, I like the ex-pat camaraderie; Adam Strange wouldn’t necessarily have palled around with Swamp Thing on earth, but here they are infinite miles away, and suddenly (once they’ve stopped killing each other) they’re friends.

The other thing that’s hard to resist about the use of the Rannian language here is how much faith Moore puts, not so much in his reader, as in himself and in the comics form. Moore isn’t a high modernist here; he’s not Joyce or even Joanna Russ — he’s telling a pulp adventure story and he wants his audience to follow a pulp adventure story. But he’s still willing to write large swathes of his narrative in untranslated code, because he just thinks he’s bad ass enough to do it. And…hey, presto, he can.

Again, one of the best parts is that you can almost parse what they’re saying, even though, thanks to the clarity of the drawing and the clarity of the pulp tropes, you don’t really need to. In fact, one of the things the comic allows you to do that you might not be able to do as easily in a movie is teach yourself the language. The ability to stop and go back and reread means that you can recapitulate Adam’s immersion in Rann, and learn the language just as he did. Cross-cultural understanding becomes a kind of puzzle (though certainly an artificially easy one.)

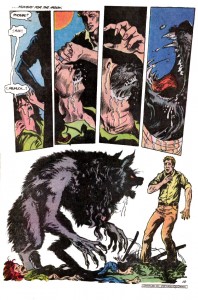

I go back and forth on how much I like Rick Veitch and Alfredo Alcala…they don’t tend to send me, but they are certainly professional, and fully up to conveying action and even nuances of emotion without the help of dialogue:

That may be my favorite panel in the comic; it’s total cheesecake for girls, and Alanna’s half-proud, half-I’m-going-to-get-that-shortly expression is just priceless. It’s a pretty great thing to have in a comic aimed primarily at guys; you get to look at the main character form the perspective of his wife. It’s analagous (and somewhat deliberately so, I think) to seeing yourself as the alien sees you — the distance Moore talks about in the story is not just of place, but of gender and love.

That’s Swamp Thing’s narrative too; his separation from earth, like Adam’s sporadic separation from Rann, is more about being removed from his wife than about being away from a particular place. Language is wrapped up in love and identity; when Swamp Thing finds Adam Strange’s bag on Rann and sees the word “Seattle,” we know that part of the impact is that the word to him reads “Abby.” Words are how we know each each other…and yet, at the same time, as Alanna’s expression above tells us, theyr’e kind of not, or at least not solely. That’s a very appropriate ambivalence for comics to have, it seems like — to see words as the metaphor for our lives and loves while simultaneously drawing a bubble around them.

In that vein, the last panel has some of Moore’s loveliest writing (as Adam contemplates his inevitably distant relationship with his newly conceived child) and its most doofy symbolism (as Alanna’s water pets form the shape of a heart.)

It’s certainly heavy-handed — but so is caring for your wife or for your kid, or, possibly, for your own chattering. Moore’s too in love with his own imagination to worry about looking dumb, which means that Swamp Thing is filled with dumbness, but also with love. It’s not a bad trade-off.

__________________

You can read the entire roundtable thus far here.

For another take on the final volume in the Swamp Thing series, you can check out Robert Stanley Martin’s review.