This is part of a roundtable on The Best Band No One Has Ever Heard Of. The index to the roundtable is here.

___________

It’s not a coincidence that gender and genre have the same root. You can see that in romance novels, in metal, in superhero comics — and in classic gospel music.

As gospel scholar Anthony Heilbut has pointed out, gospel is actually two genres — gospel and quartet. Gospel singing, which featured a soloist or chorus with piano or organ backing backed, certainly had male stars (like Alex Bradford), but the biggest names were women like Clara Ward, Marion Williams, and Mahalia Jackson. Quartet singing, featuring acappella harmony performances, had some female stars (most notably, at the tale end of the genre’s existence, Mavis Staples), but was mostly performed by men.

The division might suggest a conservative, Christian, gendered division; men and women, separate but equal, inhabiting different spheres. In fact, though, the interaction of gender and genre in gospel is a bit more complicated. Gospel quartet was overwhelmingly male. But men (quartet or gospel) often demonstrated virtuosity by singing high tenor, trespassing on women’s range, as in this amazing performance by male soprano Carl Hall with the Raymond Raspberry Singers.

Or, as another example, here’s R.H. Harris’ light, lilting take on “His Eye Is One the Sparrow” with the Soul Stirrers.

At the same time as men soared up, female singers often laid claim to the earthy low rough-voiced virile registers.

Rather than a genre in which every gender is in place, then, gospel was a heavenly stew of cross-gender mimicry and performance; the intensity of the spirit burst the bounds of bodies, making women growl down low and men soar to the stratosphere. And just as it broke out of gender, the spirit went flying from genre to genre; Little Richard arguably invented rock by imitating Marion Williams (who in turn, as above, often adopted men’s deep rumble). Contemporary pop started when a man turned a woman’s voice from God to sin.

Little Richard’s violation of gender norms didn’t stop at his voice; part of the theatricality and scandal of his act was always the not very sublimated truth that he was gay. As Heilbut wrote in The Fan Who Knew Too Much, this was hardly unusual in the gospel community either, where sexualities, like voices, often didn’t fit neatly into stereotypical norms. Ruth Davis, Clara Ward, Alex Bradford, James Cleveland, and many others were homosexual — the high notes of the men and the rumbling low notes of the women served as a kind of holy camp, the visible, theatrical, open expression of a hidden truth about both gender and God.

Perhaps the most successfully closeted LGBT performer of the Golden Age of Gospel was the high tenor Wilmer Broadnax — often referred to as “Little Ax,” to distinguish him from his brother, Wilbur “Big Ax.”

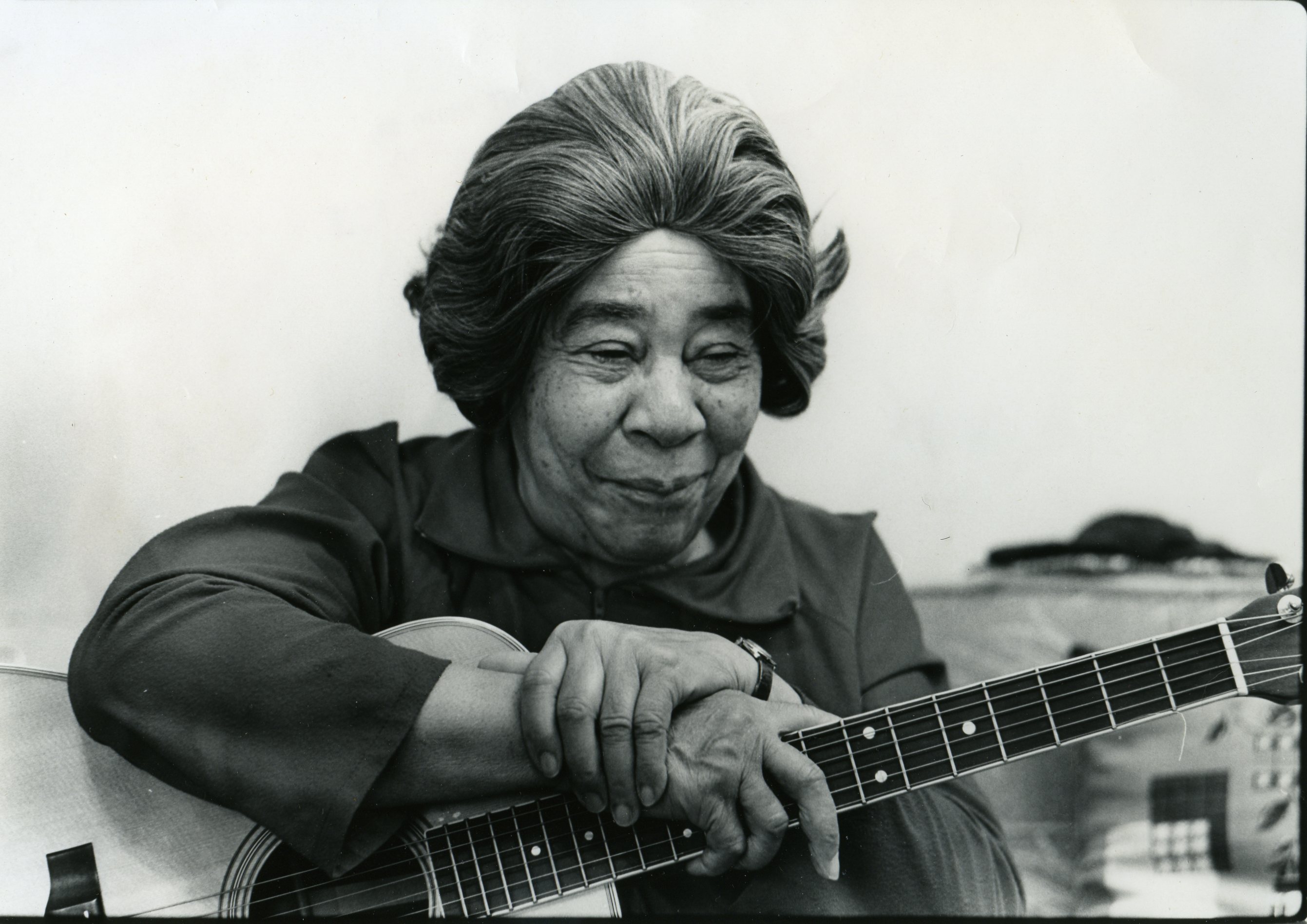

Wilmer (sometimes “Wilmur”) is shown here with the Spirit of Memphis Quartet, his most famous gig; he’s the tiny man with glasses in the front row.

Wilmer was trans. No doubt his brother was aware that Wilmer (presumably initially Wilma) had been raised as a girl, but otherwise Little Ax seems to have passed as cis until after his death at the age of 77 in 1994 (he was murdered by his girlfriend, according to Heilbut).

Broadnax’s career as a quartet singer depended in large part on him being a man; again, there were female quartets, but they were far less common, and far less popular, than the male ensembles. But his career was also enabled by the fact that men in quartets could sing like women; Broadnax’s high tenor might have been marked as non-manly or unusual in some genres. But in quartet he’s just another guy who sings in the stratosphere.

Not to say that Little Ax was anonymous. As critic Ray Funk writes about Broadnax’s first recorded group, The Golden Echoes:

“Little Axe’s lead is absolutely distinctive on these cuts. He is the high lead that takes over from the baritone of Paul Foster. His voice is sweet but almost vicious, dripping with emotion, while Foster, in contrast, would offer almost a growl.”

In this amazing 1949 track, Broadnax picks up at around 1:04, finishing Foster’s line, so they seem to fuse into a single seamless multi-octave singer. At 1:25, Broadnax goes even higher, soaring into a Marion-Williams-like ““Ooooooo!”

That’s not the only thing Broadnax borrowed from female singers, according to Anthony Heilbut.

I admired [Broadnax’s] records largely because there was something nonquartet about his delivery. It was impassioned in a way that I associated with women singers of his gneration (he was born in 1915).

You can hear that passion in this performance for the “Spirit of Memphis”, in which Broadnax grabs the lead for a few seconds from (I believe) growler Silas Steel. He doesn’t get much space to work, but his electric moans and affirmations in the background, and his short moment in the spotlight, give the song an electric charge.

Broadnax’s connection to the female gospel tradition is perhaps even clearer in these late career performances, one with the Five Blind Boys of Alabama, and one with his own group on the hoary country classic “You Are My Sunshine.”

By this time acappella style had become less popular, and the addition of instrumentation (including too-insistent drums on “You Are My Sunshin”) puts Broadnax into something that sounds more like a rocking gospel setting. Rather than the interplay of voices, he’s running vocal variations over and around the groove. If you didn’t know he was a guy, these could easily be blow-out, earthy, growling performance by one of the great women of gospel

Again, what makes this more gospel than quartet is in large part that Broadnax has lowered and roughened his voice; he sounds like a woman specifically because he sounds like a woman imitating a man.

Broadnax is not a very well-known performer. There are a few famous names in quartet singing, but they’re all folks like Sam Cooke or Mavis Staples who crossed over to secular music. Even the best known quartet singers who stuck with quartet, like R. H. Harris, Claude Jeter, and Julius Cheeks, have barely any public profile. And though I think Broadnax has a claim to be as talented as any of them, as far as the pecking order went he was a respected but second-tier performer — an obscurity among obscurities.

Broadnax’s anonymity goes beyond that, though. Even among his peers and his (relatively) small audience, no one knew him. He lived his life in the closet, and he didn’t come out until he had passed away — a secret all the more total in that its revelation caused neither stir nor interest. Those who cared didn’t know, and when folks could know, nobody (except the indefatigable Anthony Heilbut) cared.

But that seems like an overly dour conclusion for such a powerfully joyful, uncategorizable performer. Broadnax didn’t hide, unknown, all his life. Rather, he took up his name and his suit and that amazing talent, and shouted what he was, in a voice that was as male as the female gospel performers, and as female as the tenors in male gospel quartet. Even if he isn’t famous down here, he’s found his place in that circle of singers where no one is unknown, singing as a man of God.

________

Years back, when I was active on Wikipedia, I wrote an entry on Broadnax for the site. I thought I’d reprint it here for archival purposes; it’s one of the most complete biographies on the web (this site has additional information.

Willmer “Little Ax” M. Broadnax, (December 28, 1916[1] – 1994) also known as “Little Axe,” “Wilbur,” “Willie,” and “Wilmer,” was an African-American hard gospel quartet singer. A tiny man with glasses and a high, powerful tenor voice, he worked and recorded with many of the most famous and influential groups of his day.

Broadnax was born in Houston in 1916. After moving to Southern California in the mid-40s, he and his brother, William, joined the Southern Gospel Singers, a group which performed primarily on weekends. The Broadnax brothers soon formed their own quartet, the Golden Echoes. William eventually left for Atlanta, where he joined the Five Trumpets, but Willmer stayed on as lead singer. In 1949 the group, augmented by future Soul Stirrer Paul Foster, recorded a single of “When the Saints Go Marching In” for Specialty Records. Label chief Art Rupe decided to drop them before they could record a follow-up, and shortly thereafter the Golden Echoes disbanded.[1]

In 1950, Broadnax joined the Spirit of Memphis Quartet. Along with Broadnax, the group featured two other leads — Jethro “Jet” Bledsoe, a bluesy crooner, and Silas Steele, an overpowering baritone. This was one of the most impressive line-ups in quartet history. The Spirit of Memphis Quartet recorded for King Records, and Broadnax appeared on their releases at least until 1952. Shortly after that, however, he moved on, working with the Fairfield Four, and, in the beginning of the 60s, as one of the replacements for Archie Brownlee in the Five Blind Boys of Mississippi. Until 1965 he headed a quartet called “Little Axe and the Golden Echoes,” which released some singles on Peacock Records. By then, quartet singing was fading as a commercial phenomenon, and Broadnax retired from touring, though he did continue to record occasionally with the Blind Boys into the 70s and 80s.

Upon his death in 1994, it was discovered that Broadnax was female assigned at birth.[2]

References

- Carpenter, Bil; and Kip Lornell. “Willmer Broadnax”. Allmusic.

- Anthony Heilbut, liner notes to “Kings of the Gospel Highway,” Shanatchie 2000 (discusses Broadnax’s gender)

- Jason Ankeny, “The Golden Echoes,” Allmusic.

- Opal Louis Nations, liner notes to “The Best of King Gospel,” Ace, 2003

- Liner notes to Detroiters/Golden Echoes “Old Time Religion,” Specialty 1992

- For year of death, see Archived February 4, 2005 at the Wayback Machine

- For pictures of Broadnax with the Spirit of Memphis, see [1]