The index to the Comics and Music roundtable is here.

______________________

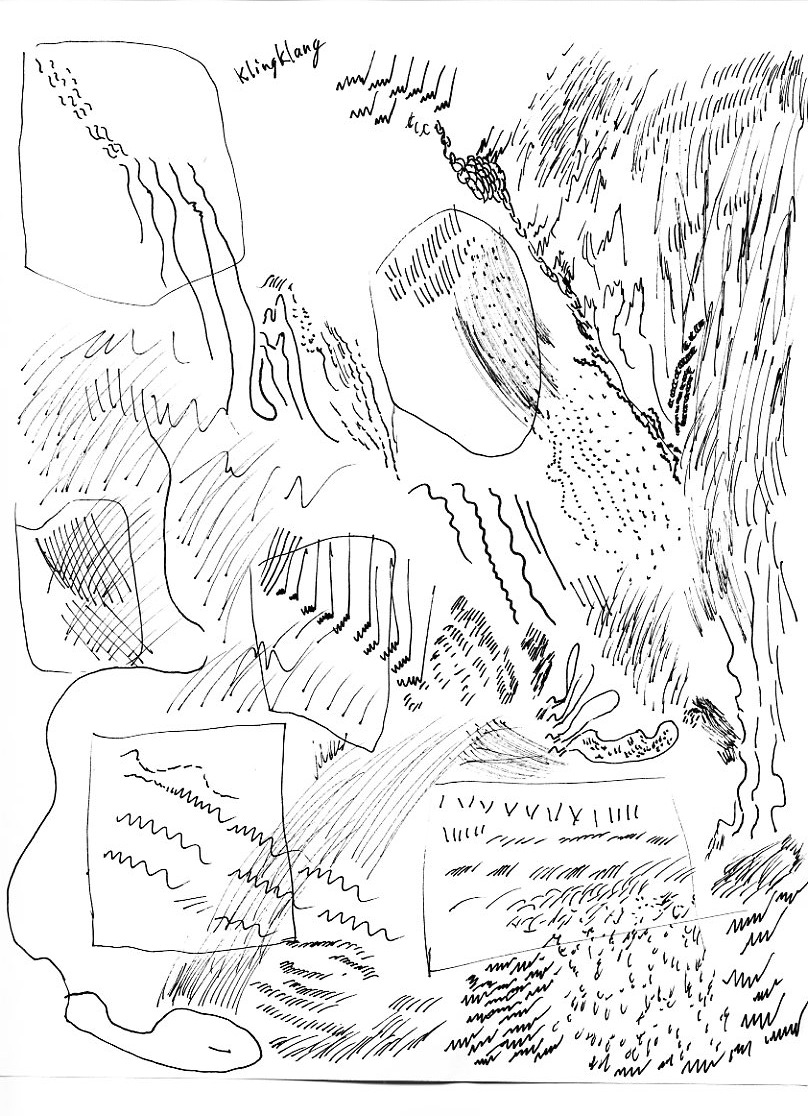

A return to the world of Kieron McGillen and Jamie McKelvie’s Phonogram: Rue Britania, which I reviewed previously here.

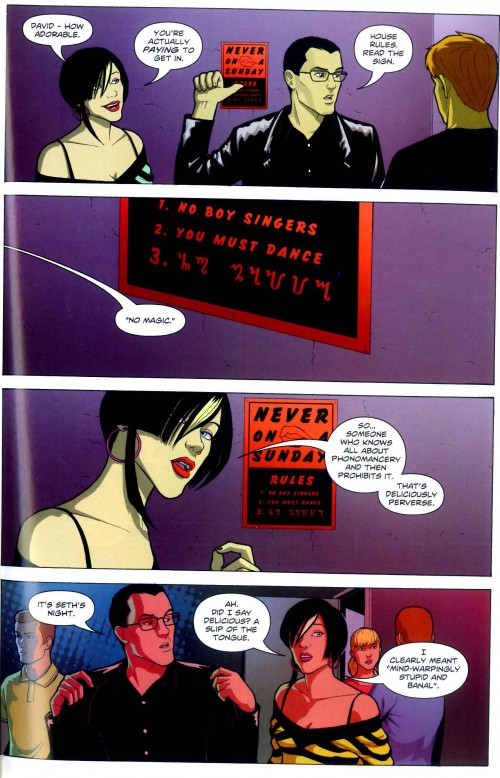

TO RECAP: When we last met our hero, he was a judgmental dickhead (and indie music snob) – the kind of asshole who thinks he knows more than you, on the one hand, and may be ultimately out to sleep with you, on the other. Perhaps there were glimmers of a kinder, less arrogant jerk buried deep within, but they were overshadowed by the self-involved nature of the narrative: Rue Britania chronicled one man’s odyssey to salvage the worthwhile parts of a youthful passion for music from the cynicism that develops after heartbreak; and to recover personal meaning from an opportunistic media narrative. By the end of the story, we’d learned that 1) bands that present themselves as the “saviours” of British guitar pop are the worst, especially if they believe it themselves; 2) most music “journalism” is hype after the fact and shockingly unconcerned with facts; but then again 3) your personal reality is, at base, probably not more real anyone else’s. This isn’t a “personal taste is subjective therefore all bands are equally worthy of fans’ love” argument, but an “everyone is entitled to feel passionately about the things they feel passionate about and to develop as fans and human beings in their own time” argument.

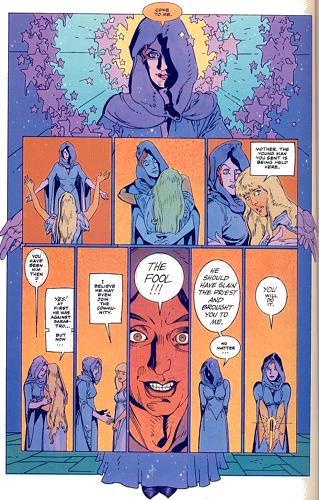

Not the narrator of Rue Britannia, but I think we all know a guy like this. Don’t be this guy! He is wrong about the Pipettes, by the way.

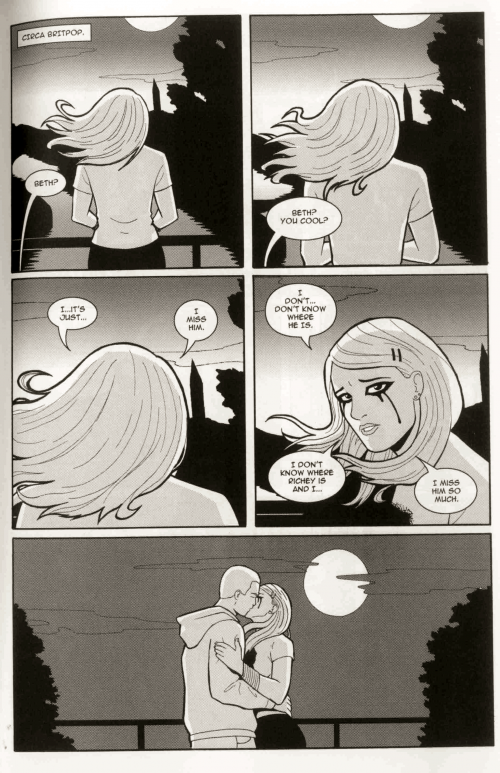

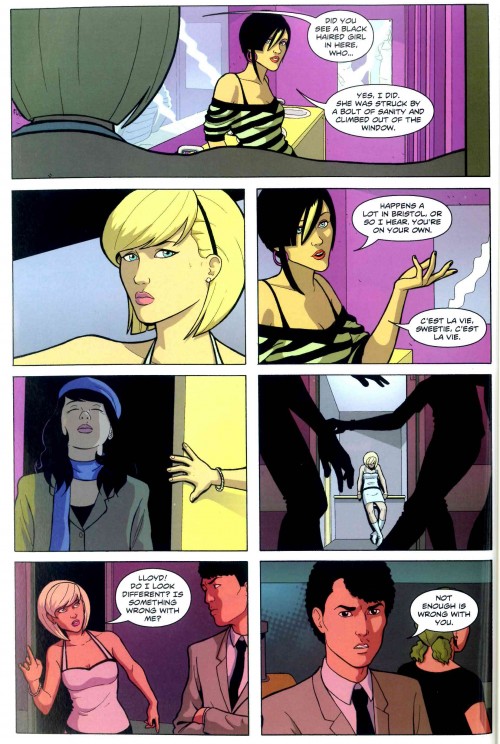

Fast forward to the Singles Club, and some of those glimmerings of decency and tolerance have blossomed. This “sequel” to Rue Britannia is less self-involved by design: there are six chapters following six different characters over the course of one night; and not one of those characters is the author. It’s more explicitly feminist than Rue Britania, too, because the first character we are introduced to –- our guide — is a perfectly nice, if somewhat naïve, young girl who loves to dance. And she, too, is a Phonomancer: a passionate fan of music able to magically channel that passion in a way that enhances her personal powers.

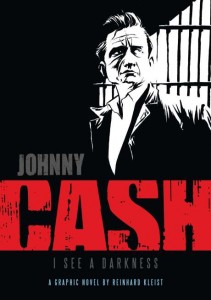

This happens to be the comics and music roundtable at HU: not just the music roundtable, and not just the comics roundtable. So I can proudly report that Phonomancer isn’t a story that happens to be about music and happens to be in the form of a comic, but is a series that draws from the energies of both. In the first volume, we spent a lot of time with a character whose “type” we recognize from both music and comics: the music snob type, always willing to tell you (or just privately think) why and how you are wrong; and the semi-autobiographical indie-comic-narrator type, out to involve the reader in his personal internal journey. The art, in black and white, with cleanly-drawn and laid-out panels ala Chris Ware or Harvey Pekar, and lots of space given over to text detailing the author’s thoughts on everything from Manic Street Preachers to NME, fits in with the style of semi-autobiographical indie comics, too.

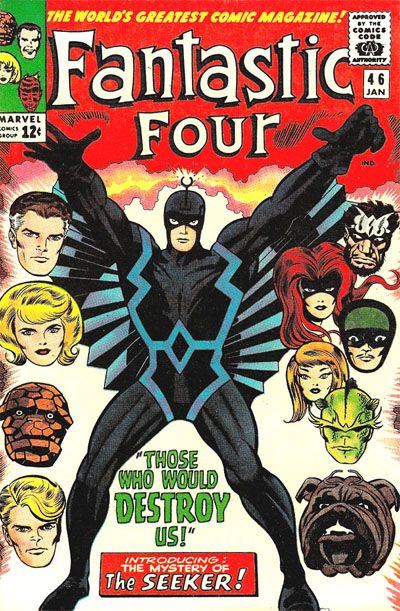

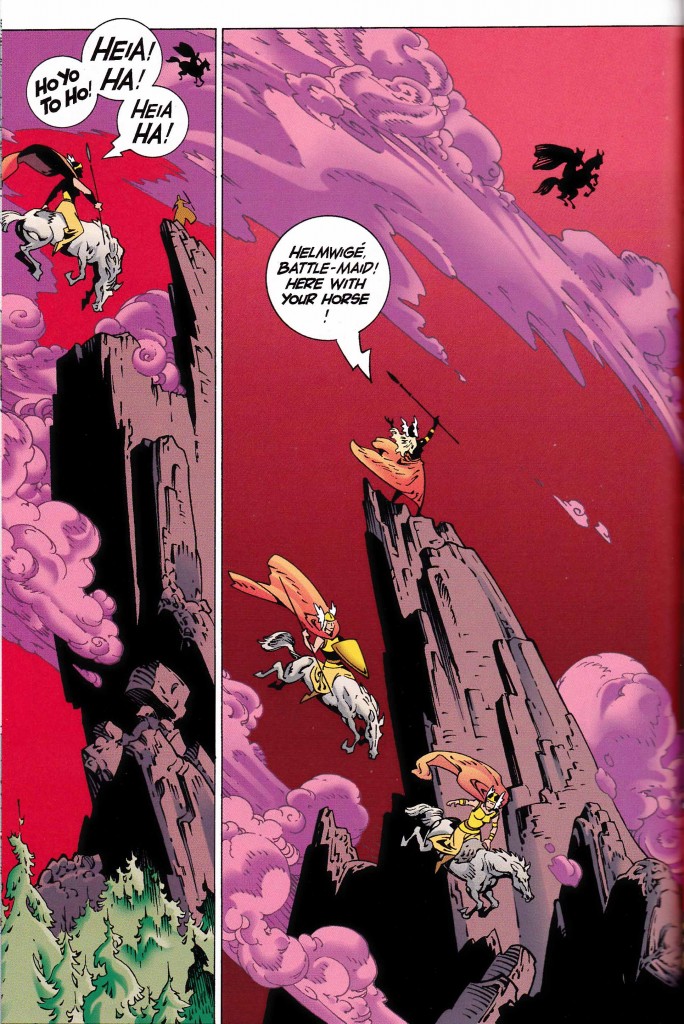

At the same time, Kieron McGillen is now writing, and Jamie McKelvie is now illustrating, for superhero comics. And some of the more action-oriented aesthetics of superhero comics have been present from the beginning, too: from the centrality of (not well defined) superpowers to the narrative; to the narrator’s final not-so-climatic final showdown with the zombie ghost of Britannia, Avatar of British Guitar Pop; to the paneling, which breaks out of the equally-sized-boxes mold of indie comics to hew closer to the dynamic style of manga, with frequent splash pages, pages laid out with an eye toward the overall balance of blacks and whites, and flow designed to draw the eye onward from panel to panel.

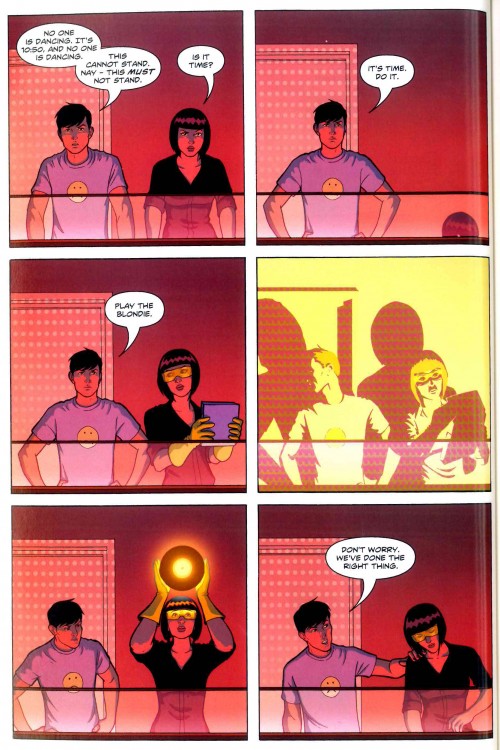

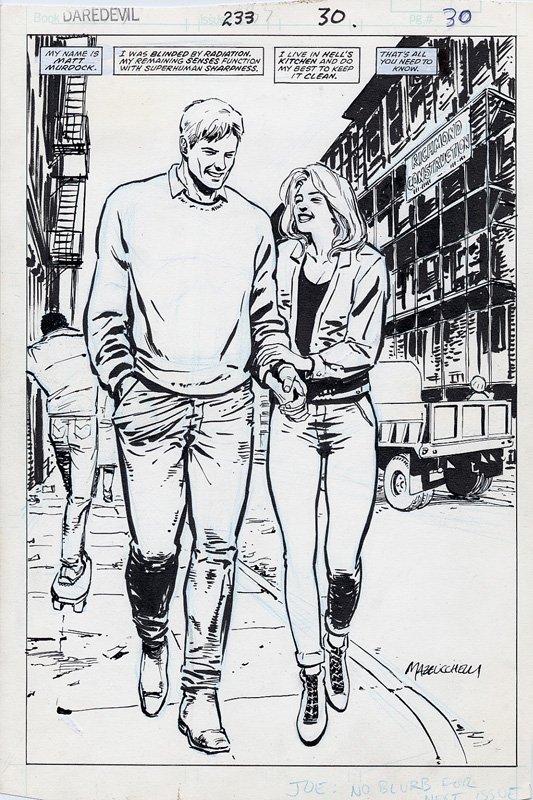

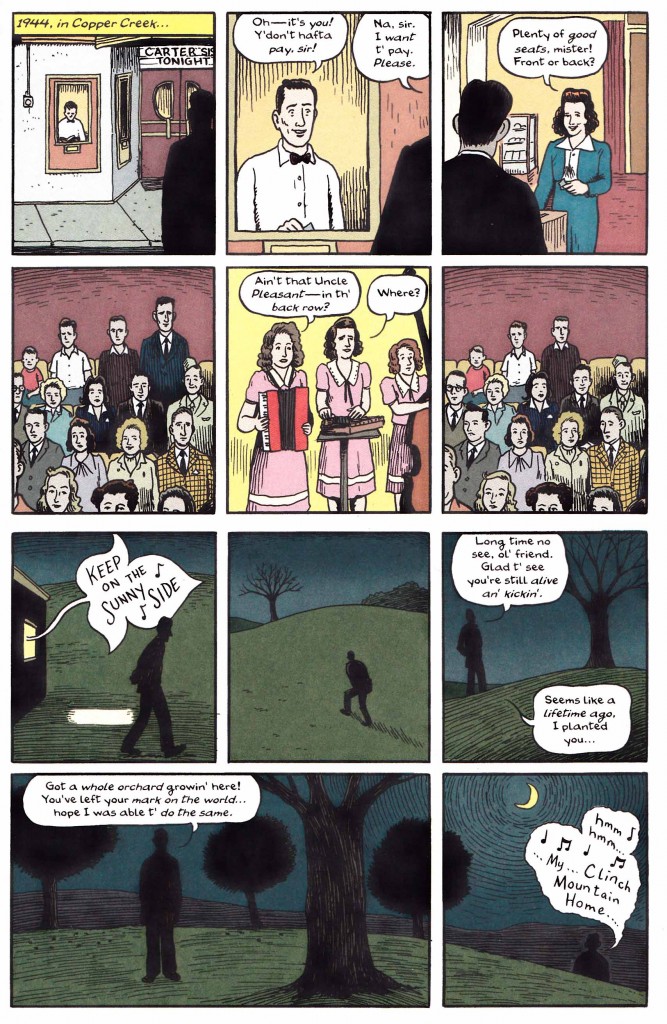

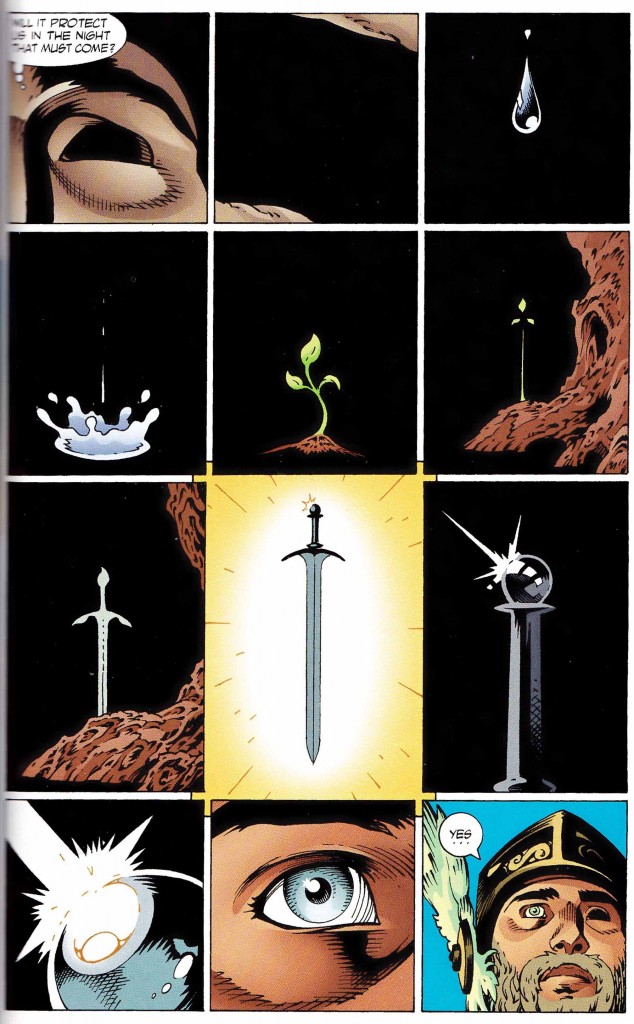

Cinematic pacing also very manga-like

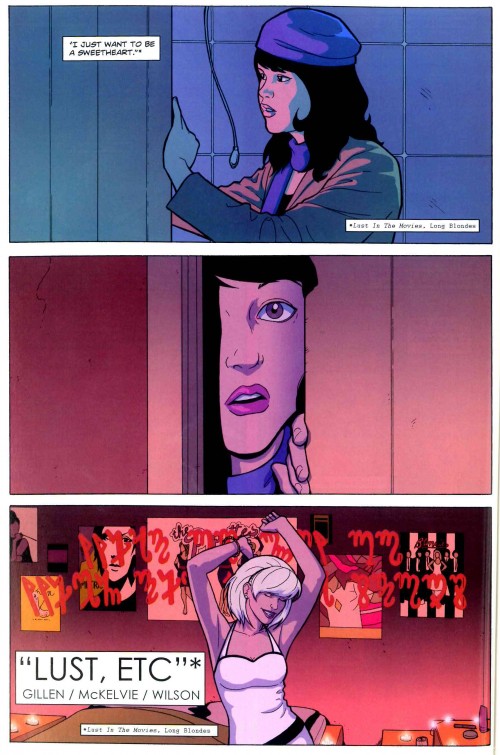

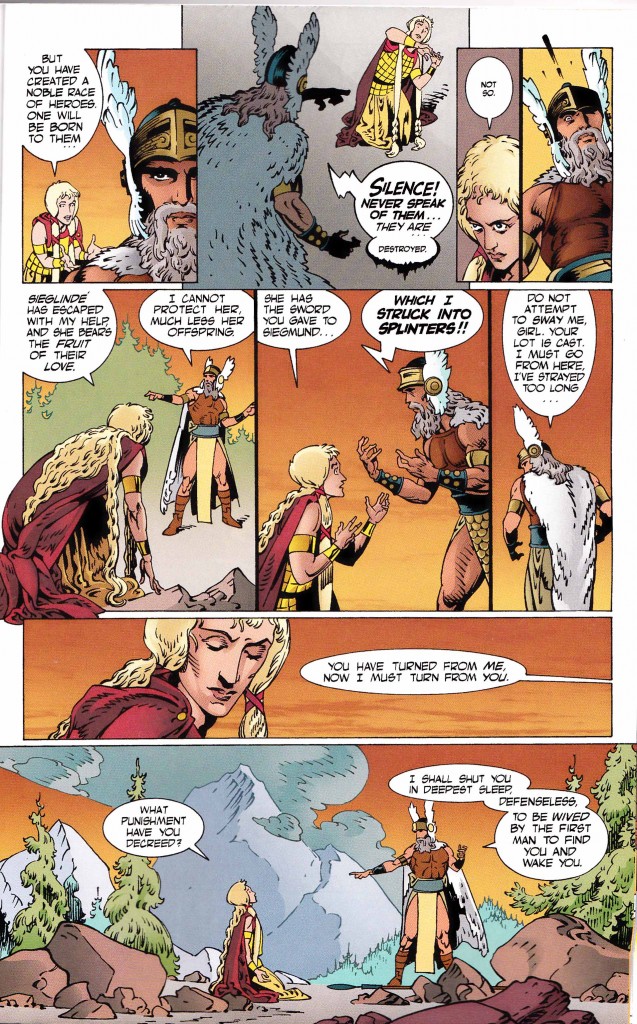

The Singles Club moves further toward superhero comics with the addition of VIVID! FULL! COLOR! And also by going into more detail on Phonomancers powers, which were underexplored in the previous volume.

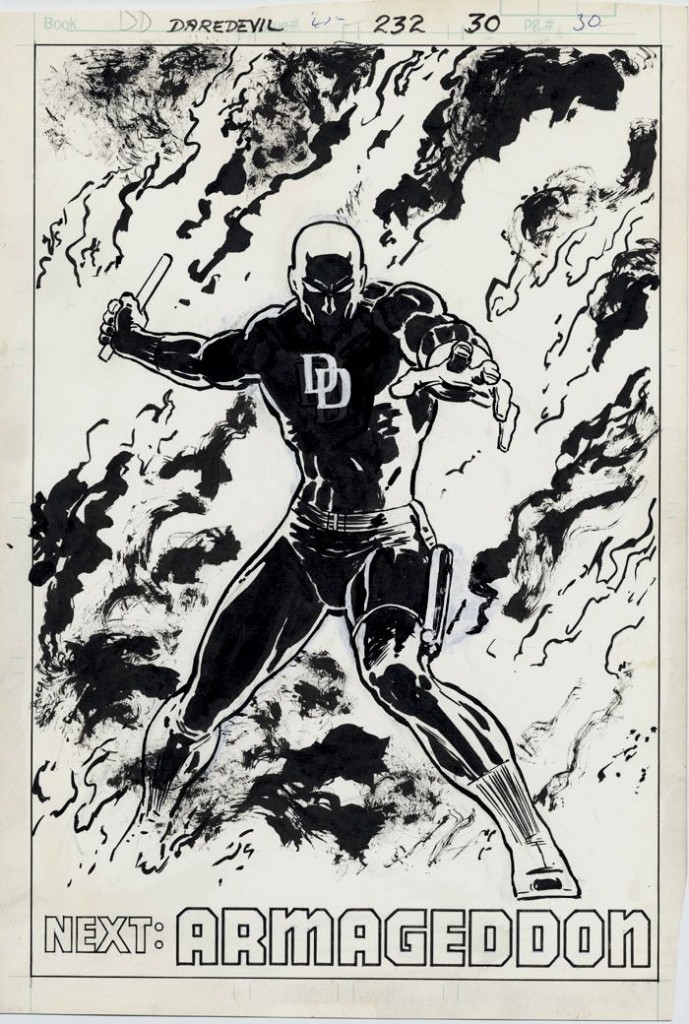

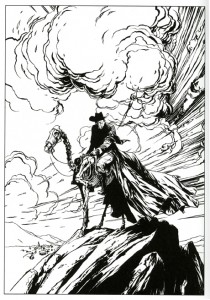

This splash page is, like, totally superhero-ish

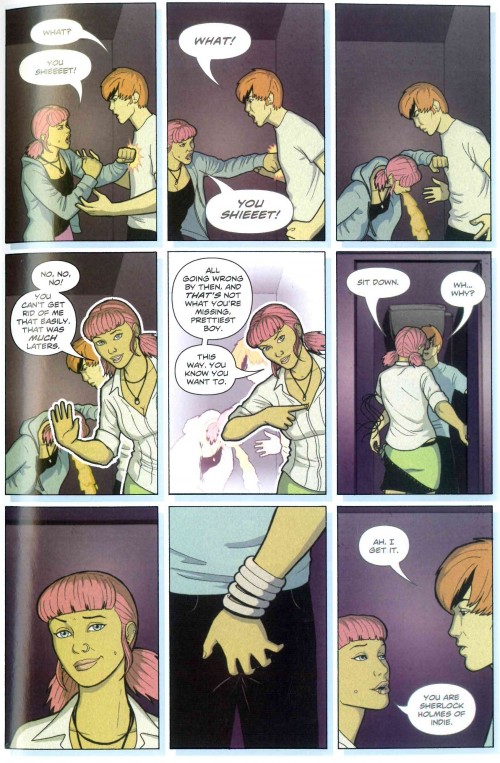

Like superpowers, Phonomancer powers are presumably unique to individuals. However, since we mostly only dealt with the author and his powers in the first volume, it wasn’t too clear what the range these music-related superpowers might be. The narrator’s power was very intellectual: he dissected pop songs in arcane rituals in order understand their totemic powers. Although there were other Phonomancers in the picture – like his friend Emily, who also appears in this volume – they were off to the side, sidelined to the narrator’s quest.

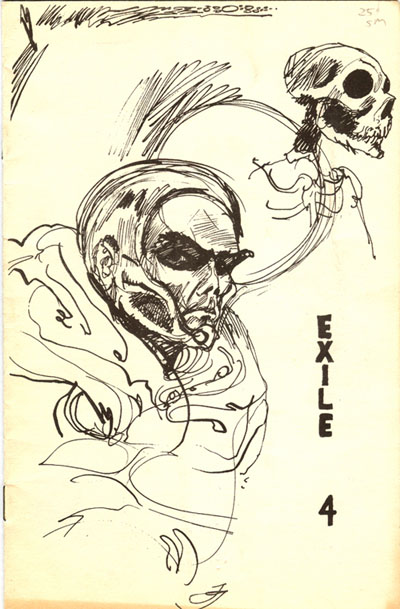

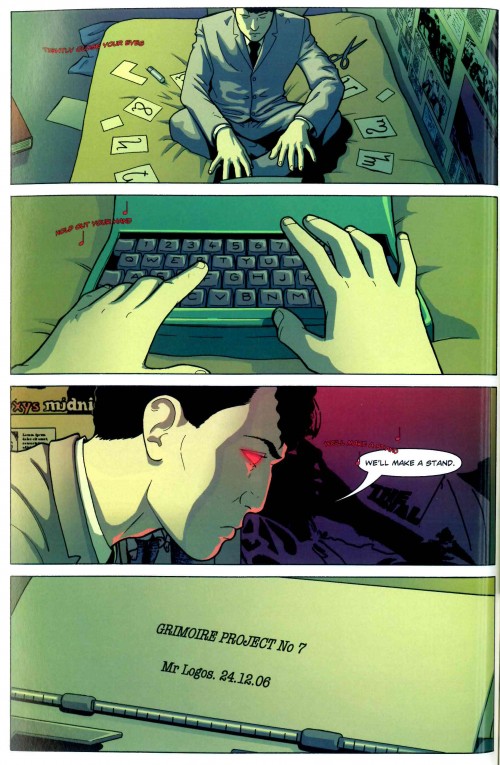

Here, too, the powers are off to the side: the comic follows an “off” day, or what Phonomancers do for fun when they’re not actively practicing magic (naturally, music is still involved). Even with that, though, there’s still more about magic powers than before. There’s the girl we met already, who uses her love of music to enhance her charisma when she dances; and her friend, who uses psychological insight gleaned from well-written songs to cloak her own personality and tear others down. And there’s the weird guy who channels obsessive creativity into a homebrew music zine:

“Mr. Logos” is, definitely, a super-villain name (not a super-hero name)

Are these characters music fan archetypes – like a music fan version of The Breakfast Club? Maybe, but those archetypes exist because they’re (often) true. In any case, what was true of the The Breakfast Club is also true of this comic: the pleasure comes from seeing all of these different types of music fan gathered together in one place and interacting with each other, rather than cordoned off into their own separate spheres of music appreciation. In this case, they haven’t been forced together by chance (assigned detention, trapped in a cabin during a snowstorm): instead, they mostly know each other, and have willingly come together at an indie dance club night.

Last time I promised a sociological explanation of music board ILX (ilxor.com). I don’t think I can really do that, but I can say that “different types of music fans bond over shared love of music, overlooking differences in style and opinion” is a basic premise of the site. Loving music as a whole more than you love any single band is a sort of defining feature of ILX, and it’s also a defining feature of this comic. At the club, everyone has different sensibilities and baggage – some relate to music in a more intellectual way and others in a more intuitive way – but they are all united by their passionate love of music, which, the comic implies, makes them more similar than different.

Another defining feature of ILX, meanwhile, is that even frequently maligned genres like chart pop and chart RnB (beloved by “nonserious” music fans like women and gay men) also have their share of supporters. It’s a male-dominated space, like most online bulletin boards – or actually most online spaces where contributors exchange strongly worded opinions on topics not solely of interest to women – but it’s a male space well-schooled in the politics of marginalization and oppression, and trained away from knee-jerk put downs. And that political focus shows up in The Singles Club too, coded into the rules of the club night:

The first rule of Fight Club, etc. Hover for alt-text if text is too small to read.

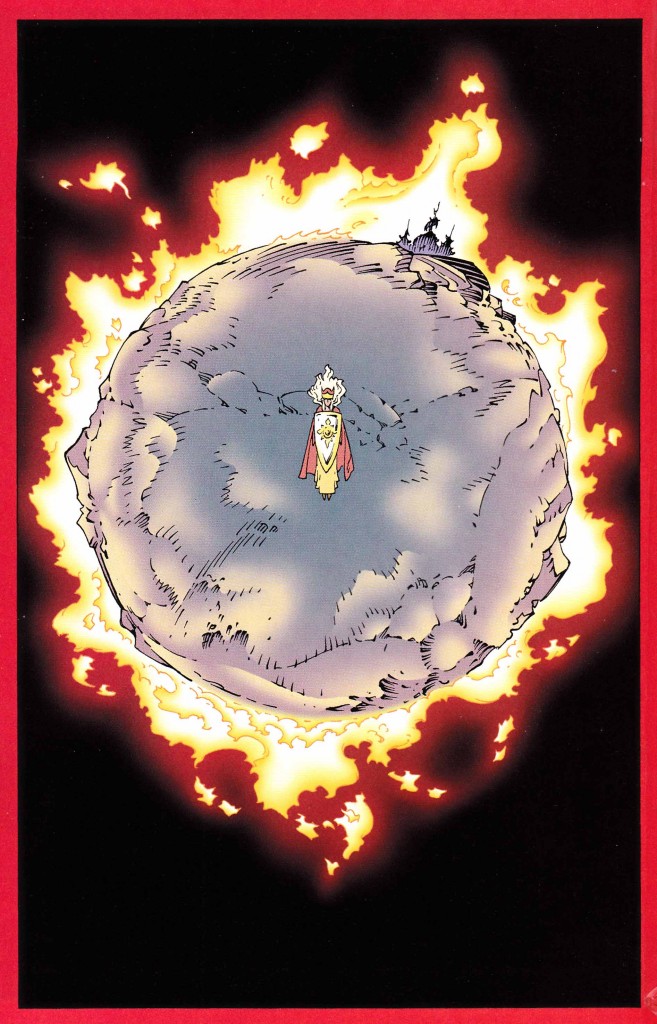

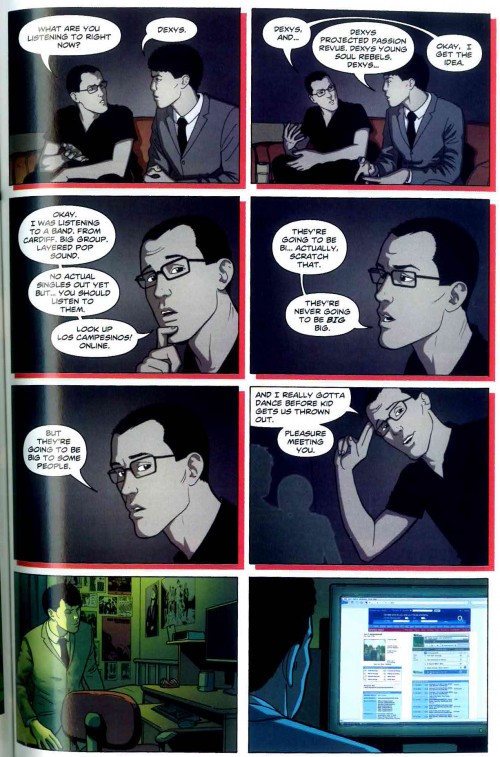

In previous entries to the roundtable, several authors brought up questions about how music can be visually depicted in comics. Well, for one, you can show the effects of music on bodies, as in the splash page above. And, for two, you can make sure enough of your references are to well-known songs by well-known artists. Compared to the indie namedropping of Rue Britania, the music in The Singles Club is a lot more mainstream… and even if there are a few artists you’ve never heard of, the authors helpfully publish a playlist at the back of the volume so you go can follow along. Some amount of accessibility is a virtue at club night, after all, as demonstrated by this scene:

While the previous comic explored the music snob/intelligent person’s sense of exclusion even from supposed “mass events” like summer music festivals, the ideological drive of The Singles Club is toward inclusiveness. Otherwise “normal” women who just happen to really really love music are included, but also other marginalized groups like the psychologically damaged and the just plain weird. Even pop music – music for the masses – can be a place for the excluded to find each other, the comic says: it’s the depth of their commitment to music that identifies them to each other, not their tribal affiliation to a particular band or genre. In fact, music is so much the domain of the weird that it’s the more “normal” people who find themselves left out:

Lloyd should be proud of himself for delivering that zinger at such an appropriate moment

Another guy I haven’t talked about much: more “chewed up” than “left out”

Speaking of tribal affiliation, though – and here I go with the sociopolitical examination of ILX, after all – in a capitalist landscape where the relationship between an artist capable of inspiring deep passion and his/her fans is, not just monetized, but aggressively monetized – thanks to a combination of declining disposable income and increased competition for the limited pool of obsessive-fan-types who will actually spend money on music – does it make sense to replace a deep love of one group with a kind of grazing behavior appreciative of many? When you learn to value songs for what you can get out of them, without allowing yourself to be too deeply drawn into a single artistic vision – if you can even find an artist with an encompassing vision, in these days of quick media exposure – you learn to fulfill your role as a consumer and, thereby, enter the capitalist landscape of music groups as commodities. Once there, you are in accordance with the realities of your environment, and friction between yourself and your environment disappears… no?

Perhaps this is a logical move for fans of music who have to live with the logic of capitalism, in other words? In an artist-fan relationship based around idolization, the artist holds the power (but only as long as they continue to play the role allowed to them by their fans: leadership is a two-way street). In an object-consumer relationship, on the other hand, the consumer occupies a position of power over the object of consumption. From a song, we can take certain ritualistic elements – a baseline, an attitude, a well-written line – while discarding the parts we don’t care for… and in that way, avoid being hurt by them. Perhaps?

On the one hand, pop music isn’t immerse yourself in your bedroom music, or even immerse yourself with fans of the same group at intimate club shows music. It is immerse yourself in beats in a collective setting music. Wide knowledge is better than deep knowledge for this purpose. But on the other hand, you could argue that deep knowledge is a prerequisite to understanding the power music can have at its most potent. Perhaps you have to be a passionate dedicated fan before you can be a passionate casual fan? Anyway, I’m just talking out loud, here.

Wide-ranging consumption is the path forward out of obsession, as demonstrated by the narrator of the previous volume of Phonogram

Passion isn’t just about knowledge, either. Half the characters are still the intellectualizing sort, but who gets the last laugh at the end?

The non-Phonomancer, that’s who

It’s okay to think these things through, but we shouldn’t forget the functions they serve, the comic suggests. The purpose of a dance night is to drink, dance, and maybe end up in bed with a stranger by the end of the night. And that’s true, even when the dance night is as explicitly intellectual and political as the one in this comic. Pop music can be smart as well as catchy; intellectual types have emotional needs too. But just because the pleasures are simple doesn’t mean they can’t also be deep; and vice versa. See also Poptimism, a London club night.

In summary: if you recognize the character archetypes, that’s good. If you like the songs, that’s good. If you enjoy the characters as people, without recognizing them as archetypes, that’s good. If you enjoy interlocking narratives, that’s good. If you agree with the politics of the author… well, you probably didn’t need to read this comic, but probably did and enjoyed it anyway.

To summarize the summary: it’s all good.