[this critic] while[s] away his lunch hour with the immortals on Parnassus

Eddie Campbell

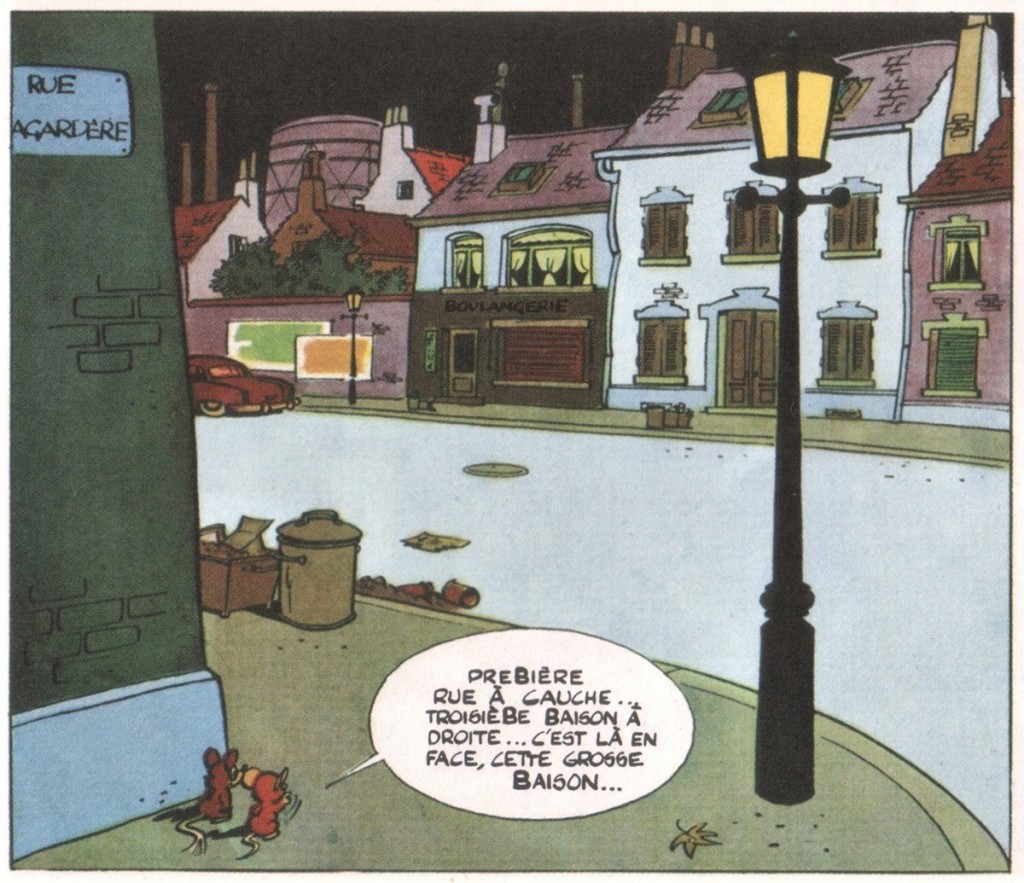

What comics give us most of all is the experience of comics. What I mean is the way a given cartoonist portrays the world- the particular kind of subjectivity that is the cartoonist’s special privilege- and the way the cartoonist tells his story from panel to panel. You can get this experience from comics whose intellectual content is fairly negligible.

R. Fiore

Waitaminnit!! This isn’t a normal library…it’s a graphic novel library!!! NOOOOOOOO!!

Sinus O’Gynus

Part One: Cicero Speaks

So there I was on Mount Parnassus, eating the usual lunchtime fare of cheese, honey, meal and Pramnian wine. Most of the Literary Greats throughout history were there — yours truly of course, as well as Aristophanes, Plato, Dante, Shakespeare, Stan Lee, and so forth. Herodotus had just started on what he promised would be an especially salacious anecdote about Darius, when in sailed Rabelais, or Big Rab as we call him at the club. Strictly speaking, he’s not one of the Greats — one of the Moderately Larges, at best — but we let him hang around anyway, out of the sort of pity one might feel towards a chap born without any arms or legs, or somebody who writes about comics on the internet.

“What ho, chaps,” he cried.

“What ho,” we replied as one.

“You’ll never believe what a frightful brouhaha there’s been down amongst the plebs. It seems that some fellows or other have dared to label the majority of EC comics mediocre qua literature, which has made them, the fellows I mean, a bit of an m. among all the nations. Now tons of other fellows have been sharpening the slings and arrows of fortune against them, the first fellows that did the daring, not the second lot.”

“Bit hard to ‘sharpen a sling’, I should think,” I said. “One of yours, Rab?”

“What’s an ‘EC comics’?” asked Cicero, who, being an old-fashioned type, had not kept across the exciting developments in modern mass media.

“Sort of a Grecian urn in papyrus form,” said Rabelais.

I was struggling inwardly with the temptation to begin a Pat and Mike routine about the identity of a Grecian urn, when Cicero burst forth again.

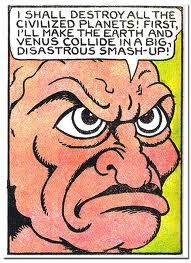

“Then let’s give these other fellows what for. Let us crush them; let us smite them; let us grind their bones to dust. For, just as Ulysses, the wily one, the Ithacan, the decade-wanderer, did, his boat at long last having reached home, with many ruses the suitors of faithful Penelope deceive, lest one amongst them, having known him for who he was, should cast his affairs into confusion, so too should we

Part Two: Lo, There Shall Cometh a Straw Man

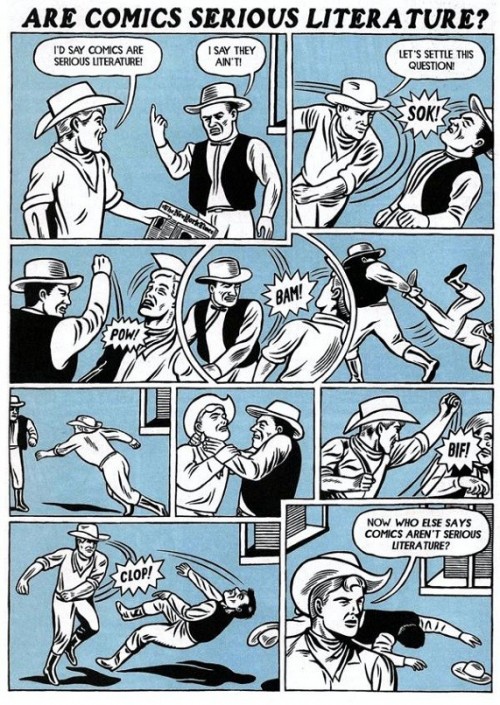

But let’s cut the great orator off there, and get right to the heart of the issue: what’s wrong with “the literaries”? Eddie Campbell’s written a combination j’accuse and manifesto against them, naming in particular Chris Mautner and Ng Suat Tong as exemplifying the type in their harsh criticism of EC comics. It’s far from clear, however, who’s really being j’accused and which manies are supposed to be fested.

Now, one way to proceed here would be to closely analyse Campbell’s piece and the reviews by Mautner and Ng, to analyse them all and tease out the different claims under contention.

That’s one way to proceed, but it would be incredibly boring for all concerned. Who cares what so-and-so said, and whether what they said was foolish under the natural interpretation, and whether their words have been taken out of context, and all the usual blah-de-blah crap that inevitably results from an internet back-and-forth?

So: let’s not try to score points or win the internet; let’s just try to figure out what’s the most reasonable position here.

With all that by way of elaborate throat-clearing, I’m going to offer a limited defence of the practice of measuring comics — at least some of the time and in certain respects — against the yardstick of literature, and, further, of sometimes judging some of them to fall short. I’ll do this by listing a set of aesthetic propositions, stated as clearly as possible, that seem to me either undeniable or at least highly plausible.

(One more throat-clear: I have zero expertise in philosophical aesthetics; I hardly know my Ars Poetica from my elbow. So what follows, the work of an arrogant dilletante, no doubt contains many fallacies and stupidities. If you know better, please rip me a new one in comments)

Here goes.

(1) Different artforms cover a cluster of different features.

Duh. Music has rhythm, melody…film has cinematography, editing…video games have playability, control schemes…and so on.

(2) Nonetheless, some of those features are shared across different artforms.

Narrative literature and film have plots, characterisation, &c. Film and painting have visual symmetry (or asymmetry), &c. &c. &c.

(3) To some extent, however limited, we can evaluate some of the features of any particular artwork independently of one another.

Thus, it makes sense to say of a comic: “the colour washes are great, but the lettering is terrible”. Or of a film: “the performances deserved a better script”. As I say, we can evaluate these features individually only to a limited extent, but even a limited extent is some extent.

Let’s now add:

(4) Some comics share some features with literature.

Specifically, narrative comics share narrative features with narrative literature — and, thereby with other narrative forms such as epic poetry, theatre or film. The Fourth World saga has a plot, as does As You Like It. Doonesbury has dialogue, as does Tristram Shandy. Lost Girls and Tropic of Cancer both have people fucking. Let’s just call these features “Narrative Features”, by which we’ll mean specifically “features shared between narrative comics and narrative literature”; and let’s call the other features of comics (wait for it…) the “Other Features”.

What counts as “narrative”?You know it when you see it, but we can perhaps say a little bit more than that. How about this: narrative content is stuff that you can describe verbally to create the same experience you would have in experiencing the artwork directly, and without losing important information. So I can say of a Fantastic Four comic that it’s set in a fictional European country called Latveria, that it features a guy in a metal suit called Dr Doom, ruler of Latveria and nemesis of the leader of the Fantastic Four. I can also say that Jack Kirby draws Latveria as a sort of comic opera European country, complete with guys in lederhosen and those funny little hats with a feather stuck on the side. This is all narrative content.

What I can’t describe verbally are the specifics of exactly how Kirby designs and draws Latveria, its people or its architecture. I can’t describe verbally the cumulative effect of Kirby’s rhythmically steady layouts, or how the placement of word balloons and narration boxes contributes to, or detracts from, the way our eyes scan the page. And so on. It’s not that I can’t say anything about these things; rather, it’s that whatever I say will be inadequate to capturing the experience of reading them for yourself. So all this stuff is non-narrative content.

This is obviously far from water-tight, but hopefully even a leaky boat will be enough to sail on with.

(5) We can evaluate to some extent, however limited, the Narrative Features of a comic, independently of the Other Features

Again, to me this seems like a duh. We can evaluate the dialogue, plot, narrative suspense, psychological plausibility…of a comic to some extent independently of, say, overall page design, colour scheme, suggestion of movement from panel to panel, and all that. Certainly, the Narrative Features are expressed through the means of the Other Features, but the same is true, mutatis mutandis, for (e.g.) film. (That is, things like plot, dialogue and character — common to film and literature — are expressed in film through means specific to film, such as actors speaking the dialogue or shots showing the action and setting.)

Note that nothing I’ve said so far entails that the Other Features of comics are merely a means to an end. The Other Features are, certainly, the means through which Narrative Features are expressed, but we might also take to them to have intrinsic value as ends in themselves. Indeed, I think they have intrinsic value, and the reason I think that is because they do have intrinsic value.

Nor does anything I’ve said entail that the Narrative Features are more important than the Other Features.

Nor does anything I’ve said entail that the Narrative Features are more important than the features that comics shares with, say, non-narrative visual art.

All I’ve said is that…well, shit, you can read (5) again for yourself.

Now, everything that I’ve said seems to me to be incontrovertible — bearing in mind that, to borrow a line from the old windbag Cicero himself, there’s nothing so stupid but that someone has said it in a comments thread, especially at The Hooded Utilitarian or comicbookresources.com. So if you want to controvert any of what I’ve said so far, go right ahead. But, anyway, if (1)-(5) were the only things in play, there’d be no “controversy” or disagreement.

The controversy comes in, I think, with the following claim, or something much like it:

(6) The Narrative Features of a comic are really important

Here’s where I’ll repeat — it would be totes omg booooring to perform an elaborate hermeneutics on who thinks what, and whether they actually think that or I’m merely putting sentiments into their mouths, or zzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzz… But I do think it’s clear, from Mautner’s and Ng’s reviews, that they would agree to (6). And, if not, then I’ll put up my hand for it — I agree to (6). The Narrative Features of a comic are really important.

But of course, the question immediately arises: what the hell does “really important” mean?

The answer is: it depends, and what it depends on is who you’re asking. We can distinguish between stronger and weaker versions of “really important”.

(6.1) The Narrative Features of a comic are the only ones that matter

Another way of putting this: having good Narrative Features is a sufficient condition for being a good comic. Pretty much no one, I take it, will would sign on for this very, very strong claim.

(6.2) The Narrative Features of a comic are so important that they outweigh the Other Features — “outweigh” in the sense that a comic with average or below-average Other Features but very good Narratve Features is thereby a very good comic

Another way of putting this: having good Narrative Features is a sufficient condition for being a good comic, unless everything about the comic is really, really, really, and I mean really horrible.

Again, it would be hard to get anyone to admit to this somewhat weaker, but still quite strong claim. But, if you wanted to build some straw men, you might speculate that that’s what’s going on when certain middling comics get a lot of praise from the non-comics press and public: they’re judged as great comics because the stories they tell are decent (say) memoirs like other literary memoirs, never mind whether they’re good comics or not.

(I totally chose the example of memoir at random, and not at all because there are a bunch of best-selling comic memoirs that are, nonetheless, really shitty comics. I could also have chosen, again as a totally random example, just about every webcomic ever)

(6.3) The Narrative Features of a comic are so important that a good comic must at least have good Narrative Features.

Another way of putting this: having good Narrative Features is a necessary condition for being a good comic. Or: having a shitty plot, dialogue, etc. disqualifies you from being a good comic. Good Narrative Features aren’t enough by themselves, but they do have to be there.

This is finally something somebody might explicitly avow. But I want to throw in one more option, closely related, which seems still more reasonable.

(6.4) The Narrative Features of a comic are so important that a good comic with poor Narrative Features has to have really very good Other Features

I’ve saved the best for last, for this to me sounds exactly right. If a comic has a stupid plot, paper-thin characters, zero ambience and banal dialogue, relies on cliche, is pretentious, panders to its audience…and so forth, then it better be one hell of a good-fucking-looking comic, you know?

I’m almost inclined to just it at that, because it seems so obviously commonsense. Surely at least part of what makes a good comic are Narrative Features, and so comics that have bad Narrative Features — in the very broad sense outlined above, where “Narrative” stretches beyond plot to include characterization, dialogue, etc. — need to have a lot of other good stuff going for them, or else they’re just crap.

So what goes on when someone like Ng or Mautner disses various EC comics? Again, I don’t want to get into hermeneutic disputes, so rather than putting words into their mouths, I’ll put myself forward as someone thoroughly unimpressed by at least the first two EC reprints in Fantagraphics’ new reprint series. These two are Corpse on the Imjin, a collection of Harvey Kurtzman’s war comics, drawn by himself or other artists, and Came the Dawn, a collection of Wally Wood’s horror and crime comics, and most of them, IMO, are claptrap unredeemed by visual virtuosity.

The main exceptions, for mine, are the two Kurtzman stories illustrated by Alex Toth, which are minimalist masterpieces. And what makes them such is precisely that the narrative elements are entirely superfluous. They might as well have no story whatsoever; indeed, in one sense they do have no story. These are comics that don’t need a plot or characters or anything else; they’re elevated into greatness through Toth’s design sense for the bare, the stark, the absence of everything but the absolute essential. But most of the other comics in these two volumes just don’t compare; whatever their many other virtues, the banal narratives drag them down.

Let me stress: the position here isn’t that a comic needs to have a great plot, dialogue etc. The position is that all stuff sure helps and, if you ain’t got it, then you’d better have everything. And it also implies that, when two comics are otherwise equal in all Other respects, the one with better Narrative — the one, in other words, that’s better “written”, whether that means written by a scripter or plotter independent of the cartoonist, or by the cartoonist herself — is the better comic.

Who could disagree?

But, if this is right, then it’s perfectly appropriate to measure a comic — at least in part — by the yardstick of literature and, perhaps, to judge it as falling short. I don’t care what you say, Kingdom Come just isn’t as well-written as The Brothers Karamazov.

Part Three: The Wet Fart Heard ‘Round the World

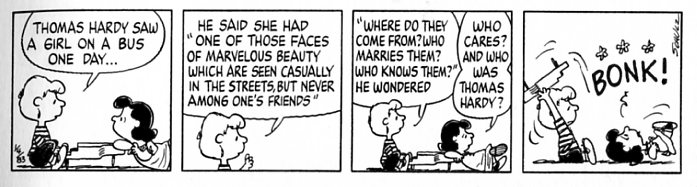

“But,” you might ask, “how could you possibly think that Narrative Features are so important? You like lots of Kirby’s comics, and he hardly wrote with Proustian modulation. You like Little Orphan Annie, which deals in the hoariest of crowd-pleasing coincidences, comeuppances and characters who barely have one dimension, let alone two. You like Little Nemo, which…dude, have you ever even tried to read the speech bubbles in those strips?”

Okay, first, you’re right. Second, it’s, um, a little creepy that you know that much about what I like and what I don’t like. I’m starting to feel uncomfortable here. Third, where did my underwear go, it was just here last night in the dirty clothes hamper, did — did you steal my worn underpants? Did you break into my house in the middle of the night, steal my underpants, and then go home to ask me mildly confrontational questions on the internet? Fourth oh shit the calls are coming from inside the house

Now, the natural response to this would be something along the lines of “don’t try to change the subject”.

All right, so yes — I like lots of comics that don’t have good Narrative Features, on a very impoverished and simple-minded notion of what counts as “good Narrative Features”. But the relevant comparisons for Kirby are not Proust or Henry James; they’re, among others, Ariosto and Homer; the comparisons for Annie are, among others, the great Middle English morality plays . There isn’t a single measure of what makes a great work of literature a great work of literature. Some of the greats are great because they’re XYZ, some are great because they’re ABC, some are great because they’re AQZ, and so on ad if not quite infinitum then at least ad quite-a-lot-of-um.

So we shouldn’t suppose that a comic needs to mimic Shakespeare or whoever to be great, any more than we should suppose that a novel or play needs to do the same. There’s lots of different ways for a Narrative to be great, and (say) depth of theme, or sophistication of dialogue — or whatever you think Austen and Trollope have that Kirby and Grey lack — are only one way to greatness.

Here’s where I really do feel the need to turn to Eddie Campbell directly. Forgot all that shit I said at the start of Part Two, about being all reasonable and all that baloney. Let’s win us the internet!

Campbell writes, a propos of Ng unfavourably comparing Kurtzman’s MAD to Aristophanes:

would we want to be stuck in [a room] with some guy who would ask: Since we already have Aristophanes, who needs Kurtzman? Since we have Erasmus of Rotterdam, why would we want Steve Martin? With Wagner still available, who cares about the Firehouse Five? Furthermore, would we let that guy organize the party music?

Granted, that build-up and punchline are lolworthy — S.J. Perelman would be proud. But, apart from that, this is an astoundingly dunder-headed characterisation of how “the literaries” feel — that, or astoundingly disingenuous. Does Campbell really think that this is why “the literaries” have come to think that, say, much of EC’s output was mediocre and a poor representative of “great comics”? Does he really think that it’s, essentially, because they’re all dickheads with a stick jammed up their arse?

To judge by his own fine comics, Campbell is no dunder-head, so this looks like it’s just an underhanded rhetorical flourish. Campbell is painting himself here as those fun-loving guys from Delta fraternity, and the “literaries” as the stuffed-shirt Dean; himself as Ferris Bueller and the literaries as the school principal; himself as Kevin Bacon and the literaries as John Lithgow. Why does the Man want to stop us having fun, man?

As self-appointed devil’s advocate for the literaries, let me say that I don’t, personally, care for Steve Martin, but: I think PG Wodehouse, and Johnny R., and Borat, and Dan Harmon’s Community, and John Stanley, and the golden years of The Simpsons, and EC Segar, and Eiji Nonaka, and Kiminori Wakasugi are as funny, if not funnier, than Aristophanes or Apuleius or, yes, Erasmus of frickin’ Rotterdam — and I think that they are therefore at least as great, as capital-G with bells on Great, as any of those guys or anything they ever did. But I also think that Ng is correct: most of MAD falls far short of that. And that’s not because I’m some snooty, hoity-toity, pointy-headed, nose-in-the-air, hifalutin, pretentious (&c. &c.) snob. It’s because, judged by the same standards that we apply to any work of comedy, it’s not that funny, nor is its satire as pointed.

Similarly, the reason I don’t think, say, Police Academy 4: Citizens on Patrol is a work for the ages isn’t that it’s too low-brow, too populist, too plebeian. My favourite comedies include gags about Eastern Europeans not understanding toilets, scat metal, and homosexual anal rape. Hell, let’s repeat this, with extra emphasis:

My favourite comedies include gags about Eastern Europeans not understanding toilets, a music genre called “scat metal”, and homosexual anal rape.

[Hello federal investigators monitoring the internet for potential sex offenders! SWM, 35, in search of SWM police officer pretending that he knows what a One Direction is and that he can’t remember September 11 because he wasn’t born yet. Must be disease/drug-free, BYO rubber chicken. No weirdos!]

[Also: toilets, scat metal and anal rape…do I detect a theme here?]

No, the reason I think Police Academy 4: Citizens on Patrol sucks is, well, that it sucks.

The issue is not high-brow versus low-brow, however much Campbell tries to make it into that. Granted, Kurtzman’s war comics and Wood’s preachies were created by not terribly well paid cartoonists in a profession whose prestige in the broader art community ranged all the way from middling to none, to be printed shoddily and sold to children of average intelligence and education, using their meagre disposable funds. But suppose instead those comics had been created by an incognito team of Ezra Pound, Max Ernst and, on inks, the ghost of Voltaire, lettered by 72 artisanal manuscript illuminators descended in a direct line from the great medieval illuminators and bred for that sole purpose, printed on priceless antique palimpsests in inks made from crushed caviar and truffles, to be sold only to MENSA members who could pass an eight-hour exam on the topic of Wagner’s use of minor chords in Die Meistersinger, at a price of seven million dollars apiece or the equivalent street-value in blood diamonds.

They’d still suck.

They’d still be dopey, ham-fisted, banal and simple-minded.

Certainly, you can disagree. About EC comics, I mean, not Police Academy 4: Citizens on Patrol — there’s no room for disagreement on that one. But if anyone does want to step forth and defend [insert any strip from, say, the first dozen issues of MAD that is generally agreed to be weak tea] as a rib-tickling, thigh-slapping laugh riot that’ll leave you in stitches, go for your life. But to defend it, you have three options:

i) Defend the Narrative Features — that is, argue that I’m making a mistake when I say (for example) that its satire is unfunny and ineffective. But this is just to accept that Narrative Features matter.

ii) Defend the Other Features as redeeming the comic –that is, argue that the rendering (for example) redeems the lack of humour or bite. But, again, this is to accept that Narrative Features matter, and thus that the comic needs more in order to compensate

iii) Argue that we — the “literaries” shouldn’t value Narrative Features as highly as we do

Campbell seems to me to circle around this option without quite crossing that line. It sometimes gets insinuated — particularly in the comments thread after Campbell’s piece: the literaries aren’t comicky enough, that we don’t love comics for what they really are, that we’re phonies. To which I say: pffft. Is this really what it comes down to, that the literaries are just a bunch of fake geek girls? Really?

Part Four: Advertisements For Myself

I’ll close with some remarks about my own artistic efforts of late, inspired by R. Fiore’s account of what makes comics great, which Campbell approvingly cites. Over the past few years, I’ve pioneered a brand-new artform to be performed for an audience of one; it involves me smashing them in the face with a cricket bat, urinating on their trousers, blasting into their ears a 300 decibel recording of a million crates of beer bottles being smashed, tattooing obscenities on their genitals, and finally I take a dump on their mom’s grave while watching Police Academy 4: Citizens on Patrol. I call this new artform “smashing them in the face with a cricket bat, urinating on their trousers, blasting into their ears a 300 decibel recording of a million crates of beer bottles being smashed, tattooing obscenities on their genitals, and finally I take a dump on their mom’s grave while watching Police Academy 4: Citizens on Patrol“, or STITFWACBUOTTBITEA300dROAMCOBBBSTOOTGAFITADOTMGWWPA4:COP for short.

(I wanted to call it “The Aristocrats”, but apparently that was already taken)

Now, some critics don’t understand this new artform, this Tenth Art; they claim it cannot measure up to the artistic heights of something like The Big Bang Theory or Curb, the debut album by mainstream grunge superstars Nickelback. They say that it has no artistic merit; it’s not funny, or interesting, or clever, or illuminating, or skilful, or anything else that any work of art in any other medium has ever given us.

But these critics — the “Artistics” — miss the point entirely of STITFWACBUOTTBITEA300dROAMCOBBBSTOOTGAFITADOTMGWWPA4:COP.

STITFWACBUOTTBITEA300dROAMCOBBBSTOOTGAFITADOTMGWWPA4:COP cannot be reduced to its bare parts as if it were a mere combination of being smashed in the face with a cricket and having your trousers pissed on and the rest of it. STITFWACBUOTTBITEA300dROAMCOBBBSTOOTGAFITADOTMGWWPA4:COP is an alchemy of all those things to create something new under the sun; STITFWACBUOTTBITEA300dROAMCOBBBSTOOTGAFITADOTMGWWPA4:COP provides that ineffable something, the je ne sais quoi that is the BYUWACBUOYTBTSOAMBBBSA300DIYEAFIJOOYMGWWPA4COPist’s special privilege, the experience, most of all, of BYUWACBUOYTBTSOAMBBBSA300DIYEAFIJOOYMGWWPA4COP.

Besides, if I might borrow one last line from Cicero:

Your mom was totally into it.

…there, is that literary enough for ya?

Image attribution: John Belushi in Animal House. Image taken from here, although I don’t think they created it.

The entire Attack of the Literaries roundtable is here.