The entire Twilight Roundtable is here.

____________________

There’s a good chance that many of you are here reading this article because you, like everyone else you know, incontestably hate Twilight. Do you ever wish it would just GO AWAY? Are are so sick of hearing about Edward and Jacob, that you want the whole thing to just disappear from existence? Well you are not alone. This article is, in fact, about hating Twilight but the twist is… I don’t hate it. Actually, I sort of like it.

But, I am sure that the odds are in my favour that you probably do hate Twilight, or you are at least annoyed with it in a way that unsettles you. But why? Is it because you don’t think the books are any kind of sterling literature? Is it because Bella Swan isn’t “powerful” enough as a female role model? Is it because you don’t like Kristen Stewart’s ever-glassy visage, or Robert Pattinson’s combination of glittering epidermis and hair gel? Is it a plot hole? Ask yourself right now, is there something about Twilight narrative that you specifically hate?

If the answer runs something to the tune of, “well, I don’t hate it or anything… I simply just don’t want to read or watch the damn thing,” good for you! But another hypothetical, if you’ll humor me: if tomorrow one of your good friends, maybe your partner, or boss, or child walked up to you told you they had read the entire Twilight series and actually really enjoyed it, would you still feel the same way about them? Any chance your respect for them would take a dip, if only marginally? Taking this one step further, is there any other book they could have claimed to have read and enjoyed that would have left the same affect?

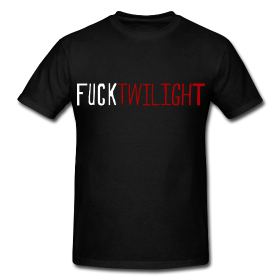

I ask because it often looks as though the internet has regressed into a goddamn hunting ground for Twilight fandom. Not only are Twilight hate sites rampant, but Twilight hate memes are some of the most pervasive images circulating on social networking sites daily. People have become eager anti-fans of the series, creating an active subculture that manifests in hateful dialogue and value judgements on a seemingly arbitrary slice of a very large pop culture pie. Instead of putting effort into enjoying their own “things” they spend their time not enjoying Twilight. Loudly.

The majority of these memes fall into a few distinct categories:

1. I hate Bella memes: detailing someones hatred for Kristen Stewart or Bella, or an interchangeable mess of the two; because she isn’t a strong enough role model or she doesn’t react to things in a “proper” way. Usually measures her against other nerd-heroines Katniss, Hermione, or Buffy etc.

2. “Still a better love story than Twilight” memes: People illustrating their knowledge of the romance genre by juxtaposing the tag line against an image of something that either is or isn’t a good “love story”. Examples may be: a photo of a guys right hand, Tom Hanks and Wilson, the movie poster for dumb and dumber, a horse mounting someone etc. The most offensive memes of this category and ones that blend into type 3, implying that love story chosen for pictorial representation is invalid in some way. By choosing Broke Back Mountain as their example, this meme implies both that Twilight is a “worse” love story and that there is something repulsive about BrokeBack Mountain as well.

3. One of the most offensives types is the “Still not as gay as Twilight” meme: If you stumble upon this cache of memes you may think this is a simple case of some ignorant person who doesn’t care about gay rights using the term “gay” as interchangeable with “bad”, but it is actually much worse than that. What is often happening in these memes is the creators are using images of people who are gay, or who are performing acts that could be interpreted as gay, and then adding on the tagline of “still not as gay as Twilight.” So what they mean is in fact, Twilight is bad, therefore gay is bad and in fact Twilight, somehow with it’s heterosexual love triangle is the “gayest,” and therefore the “worst.”

4. The last category of memes don’t have a unifying caption. They instead are memes that include a male figure who, either dumps, beats, or murders his girlfriend/wife/random woman when she mentions she has watched/read/enjoyed Twilight. A disturbing illustration of desire, hyperbolic or not, brings me to the point of this article.

These anti-Twilight memes and Twilight-hate culture on the whole have very little to do with Twilight, and a lot more to do with systemic sexism and rampant misogyny, and the whole mess could use a feminist perspective. I know, I just dropped the S, M and F bomb in one sentence but hear me out here: we live in a culture, that does not want women to embrace their sexuality, and it REALLY doesn’t want them to do it in a “geeky” way. The original phenomenon wrought by the Twilight books was simply a bunch of girls geeking out over a series of books subsequently turned into a successful film series. The story is no different than the phenomenon of, say, people geeking out over Harry Potter or Batman, and their inevitable film series. The only difference being, when it is women who are the distinct majority enjoying themselves, everyone else gets condescending, snarky, or even angry.

If you need proof of this prejudice existing in other fan cultures you can look at any examination of the fake geek girl problem that is supposedly plaguing society right now. For a notably recent example, take a look at the articles about the #1reasonwhy detailing why women are not welcomed in the gaming industry as creators or participants. It’s a long time coming, but it seems people are finally willing to call the lack of female presence in nerd subcultures out for what it is: sexism. Normally this sexism takes place in conversations about a women’s validity as a geek and therefore her exclusion from that culture. Conversely, this sexism in nerd subculture is much more difficult to name when it is directed at a grouping that is almost entirely female, where men may even feel excluded i.e.Twilight.

Let’s go back in time a bit to examine this further. Before the Twilight movies were released the books themselves were extremely popular among young adult (YA) and female readers. Most people at this point had likely never heard of Twilight. This was a time before Twilight was connected with its silver screen players Stewart, Pattinson, or Taylor Lautner, though word of the films’ production were widespread and the pop culture “aura” around it was entirely different. Twilight has been around since 2005 when the book made its debut and immense popularity. People read Twilight in the way they would have read any other YA series that was hot at the moment and visibly loved it, so Meyer continued to write more of the series. These books-turned-films remain popular because people enjoyed reading them. They read them, as I read them: as a consumer ignorant of the cultural impact the books would have, happily indulging in the fantasy/horror/romance narrative in the same way I would indulge in any other piece of pop fiction or television. Women were lining up outside of bookstores, cosplaying as vampires, speculating about the future of the series, which characters would live or die, and what team would win the battle for Bella’s heart. Utterly captivated by the world Meyer had built, these fans (predominantly women) were just geeking out.

Those on the inside of this culture, were also just enjoying reading, something that is unfortunately rare this day in age. For the most part at this point the Twilight culture was unknown and left alone, yet the first movie’s release signaled to the rest of contemporary pop culture that the series — and it’s fans — had successfully arrived. When outsiders looking in saw these large gatherings of Twilight fans outside of theaters, they were spectator to a group enjoyment that didn’t quite synch up, and met the source material with confusion, aggression, and hatred: a large group of females enjoying themselves. So they looked on them with the same hatred normally reserved for girls lining up for Justin Bieber concerts.

Twilight allowed for a entire movement of young women to revel in not only a fantasy world and fandom without fear of exclusion (like say worlds in comic and video game subcultures) and it also allowed them to revel in their sexuality, openly, by fantasizing about the imaginary Edward and Jacob. This reveling only became stronger when those fantasies saw a fleshed out actualization in the performances of Robert Patinson and Taylor Launter. Women everywhere had tiny intertextual nerdgasams upon the realization that Harry Potter’s Cedric Digory would be playing Edward Cullen.

Every action will have an equal and opposite reaction, so the groundswell enjoyment of the Twi-hards was abruptly stomped out by a larger cultural consensus that Twilight’s success indicated the end of times, or something equally as dramatic. This was partly the result of comic and sci-fi conventions being taken over by thousands of adoring fans looking to see whatever Twilight movie actor was there signing autographs. People were pissed off about the ways in which Twilight was somehow ruining their lives, so they started making memes about it.

For myself, the irony often lies in the memes that are confronting Twilight for being sexist itself.

For example, one meme shows a photo of Kristen Stewart and reads, “Women’s rights? lol I need a man to live.” Disregarding the finer details of Bella’s character, her general independence, her lack of desire to get married, her refusal to obey Edward’s constant commands, and her place as the sexual aggressor in her relationship. In the novels, it becomes very clear to a reader that Bella, who is constantly kissed and caressed but never fully satisfied, is motivated to become a vampire in part because of her veritable dripping anticipation to finally get her freak on. It is easy to read these books as a story about a girl who is so horny over the fact that the sexiest man alive wants to be with her for some reason, that she will literarily give her own life to have sex with him. She doesn’t need a man to live, she wants to fuck a man, she wants to marry him, she wants to conquer him, and she wants to become immortal, all within her rights as a woman. The long-awaited build up to any actual sex over the course of the series has, hilariously enough, garnered the series the monicker “abstinence porn,” offering an enjoyment that is arguably more exciting than if the characters were just having sex all along.

The majority of cultural examinations of Twilight seem to be a reaction that simplifies the novels and films by considering them “not feminist enough” to be consumed by supposedly naive young girls. Plenty has been said of the ways in which Twilight is not as feminist as, say, The Hunger Games or Buffy, both of which were pop culture sensations of a similar nature as Twilight that didn’t attract any of the mass hatred possibly, I would argue, because of the gender diversity in the fan base. Memes often frame Bella as a bad female role model, privileging female identification with characters like Buffy as a more positive alternative. You can read more about this here.

The irony I would cite in this beyond what has already been said about this type of meme, is that comparing Buffy and Bella makes very little sense considering that they are constructed for different purposes. Buffy is kind of like Superman: she has this gift, all these powers, she has super strength and a destiny to save the world. This kind of identification is usually a “look up to” connection as opposed to a “I feel so similar to” connection that readers may have with Bella. Bella essentially functions in the same way as a Peter Parker. He is a plain and boring studious type before he is bitten by a spider and granted his powers. Just a normal everyday guy who is granted superpowers. Fans have identified with Bella in the same way. There is a twofold desire that encompasses not only the sexual desire for Edward and Jacob but also the desire for superpowers, to become something, or someone more. Comparing Bella to Buffy to make a point about the degree to which Buffy and her readership are more feminist, virtuous and empowered is akin to a meme juxtaposing Superman and Spiderman and claiming that those who identified with Spiderman are inherently “lesser” men. I suspect that this specific type of meme, comparing female characters is likely often actually created by women attempting to make a point about empowering our gender, but the inadvertent effect involves a backwards girl hate.

Sometimes women do not fit our definition of what female “strength” should look like (especially when that strength often involves merely repurposing a traditionally masculine rhetoric of strength), but that does not make them weak. We see a similar problem in the mass treatment of Kristen Stewart by both fans and anti-fans of Twilight. It became trendy to critique her for the plainness that was so integral to her character in the novels. The cultural opinion surrounding Bella in the narrative is only compounded by the hatred and slut-shaming directed at Stewart in real life, citing her personal affairs, and using a completely unrelated element to admonish the storyline. The open, widespread condemnation the women in these narratives weak, or anti-feminist, or masochist, or submissive signifies to women who identify so strongly with these characters that the same must be true about themselves. Why can’t we look at these issues of female empowerment as a complex system of women who are still having difficulty coming to terms with their roles in their relationships, instead of simply pushing these women out of the feminist “us” camp and into the “them” camp where they will be considered lesser women.

The Twilight-hate culture is fueled from two sides. One side is the meme culture that I have been citing and the second is typified by articles such as this) which have decided to examine the series as an anti-feminist archetype, and seem to only be able to see the narrative through that lens. Instead of examining the way a narrative such as this is empowering for female sexuality, or examining the ways that these female fan communities allow women to express their sexual desires in a way they are not allowed to in day to day life, the anti-Twilight camp focuses entirely on Edward and Bella’s relationship. It simplifies the narrative into a tale of emotional abuse in which Bella is nothing more than a passive onlooker in her own life. Instead of examining Rosalie’s (One of Edward’s sisters) revenge fantasy in which she, as a vampire, goes back and kills a group of men who gang raped her as a human they focus on Edward “wanting to kill” Bella. Instead of examining Jasper’s description of his previous abusive relationship and how he overcame that, critics want to depict Edward as abuser. Instead of examining the ways that Bella outsmarts her supernatural enemies, detractors focus on the ways in which Edward physically saves her. Instead of examining the ways that a new depiction of feminism may be emerging in popular culture many are deeming Twilight as the death of feminism, or as one article put it “The Franchise That Ate Feminism.

I am not trying to argue for extreme literary complexity in any of these works. What I am arguing for is extreme cultural complexity. The simplistic nature you may see in these characters does not mean that our analysis of the series, and therefore its resulting fan culture, should be just as simplistic. Feminism is not dead, this is something I can guarantee you. For years I have been hearing claims that Bridget Jones, or Sex in the City, or Jersey Shore, or a variety of things were to be “the death of feminism.” Saying that Twilight’s anti-feminist nature will confuse our world’s young girls into abusive relationships or unwilling submission is in my opinion a regressive, sexist notion itself. It is implying that the women reading this narrative or any other cannot reason or deduce for themselves the degree to which they identify with any given fiction, nor ideal of sexuality. If young girls want to read Twilight, if they choose to read Twilight, if they choose to enjoy Twilight… and you tell them not to because it’s “wrong”, or you tell them that their enjoyment reflects their own weak intellect — well, that doesn’t bode well for feminism to me.

On this note Meyer herself says:

In my own opinion (key word), the foundation of feminism is this: being able to choose. The core of anti-feminism is, conversely, telling a woman she can’t do something solely because she’s a woman—taking any choice away from her specifically because of her gender… One of the weird things about modern feminism is that some feminists seem to be putting their own limits on women’s choices. That feels backward to me. It’s as if you can’t choose a family on your own terms and still be considered a strong woman. How is that empowering? Are there rules about if, when, and how we love or marry and if, when, and how we have kids? Are there jobs we can and can’t have in order to be a “real” feminist? To me, those limitations seem anti-feminist in basic principle.

Admittedly this isn’t the precise way I would define feminism, but I think what Meyer is saying here is very important. The key being that you don’t tell a “woman she can’t do something solely because she is a women” by placing acceptable “limits on women’s choices.” We need to allow girls and women to choose what they want to enjoy, and we also need to learn not to taint that enjoyment because we feel that women enjoying themselves threatens some higher, reserved ideal of feminism. If there is one thing that I am sure could be the death of feminism: it is us telling young girls that they are not feminists.

I think Twilight is one of the best things to happen to young female sexuality in the same way that I think that Fifty Shades of Grey is one of the best things to happen to adult female sexuality. We live in a culture that is overwhelmingly sex negative, particularly for women. If the only porn that women will consume is “abstinence porn” and its fan fiction, that is okay with me. Who CARES whether or not the writing in these novels meets some arbitrary level of lexical intricacy or allegorical nuance? Young adults are reading, and they’re privy to a literary artifact which offers a safe, enjoyable exploration of their perfectly natural sexual impulses. No one examines male pornography and critiques it for the quality of its “love story” or sentence structure; in the same light women should be able to indulge in media that is just as permissibly “bad.” I am just so so so happy that women are looking their sexual desires in the face and confronting it as a regular component of their lives in society. Bella and Anna are not the categorically defined “kick ass” females that we have BEEN TOLD are good role models. But if they are characters who plenty of women identify with on a mass scale, then we ought not to focus on the lack of empowerment as defined by their contemporaries, and instead recognize that women of our society identify SO strongly with these female characters regardless. Not because every woman who reads Twilight or 50 Shades is a submissive antifeminist who simply wants to be told what to do, but because women are starving for the type of sexual fantasy that men are allowed to indulge in guilt free everyday. What we can glean from this, also, is that the definitions of female empowerment should not be so static or rigidly defined because dominant character aspects in any one popular text. Female empowerment is not measured by a ratio of aggression, independence, intelligence, or even sexuality, or the mere sum of these parts; rather, the empowered feminist-positive ideal is a comprehensive whole built of of these aspects, but with varying degrees as our role models slip and segue through different contextual representations: Buffy and Bella are every bit as ideal because they are constructed so differently for their own respective universe.

Lev Grossman put it much better than I ever could way back in 2008 when he said:

What makes Meyer’s books so distinctive is that they’re about the erotics of abstinence. Their tension comes from prolonged, superhuman acts of self-restraint. There’s a scene midway through Twilight in which, for the first time, Edward leans in close and sniffs the aroma of Bella’s exposed neck. ‘Just because I’m resisting the wine doesn’t mean I can’t appreciate the bouquet,’ he says. ‘You have a very floral smell, like lavender … or freesia.’ He barely touches her, but there’s more sex in that one paragraph than in all the snogging in Harry Potter. It’s never quite clear whether Edward wants to sleep with Bella or rip her throat out or both, but he wants something, and he wants it bad, and you feel it all the more because he never gets it. That’s the power of the Twilight books: they’re squeaky, geeky clean on the surface, but right below it, they are absolutely, deliciously filthy.

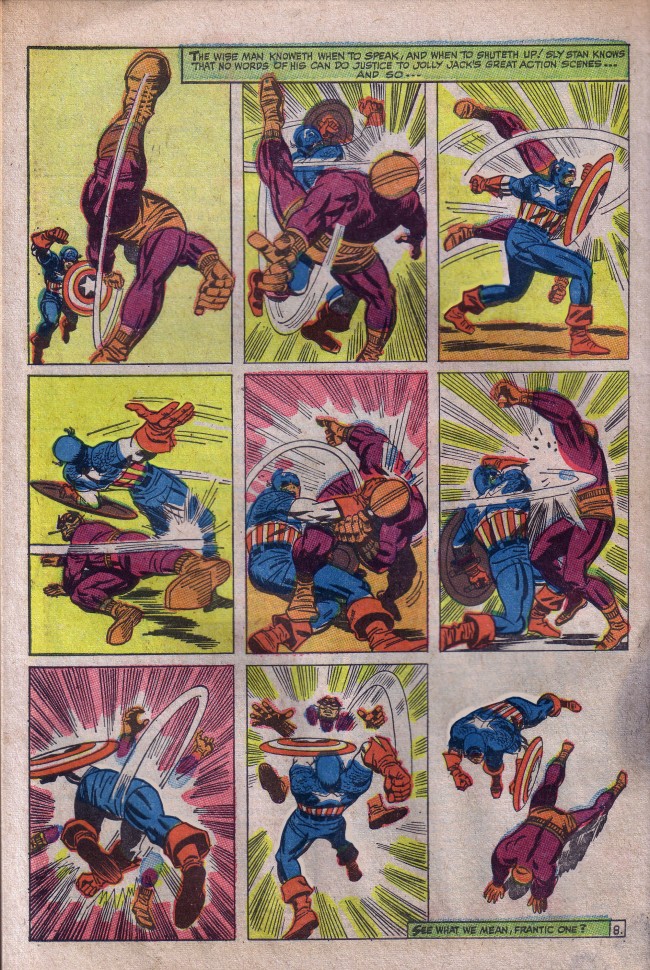

Will we ever be able to return to a state of mind where we see our daughters reading Twilight the same way we would see our daughters reading superhero comics? Will it ever again appear to people as “squeaky geeky clean”?

Let me get one last thing straight: I fucking love memes. I think a well crafted meme is like a work of poetry, when the subtext is strong and the juxtaposition is subtle and surprising. A good meme and the laugh that accompanies it is revitalizing, like a good cup of coffee. But for every well constructed meme there are about 10,000 shitty memes. I would say that all of these memes above are not popular, not “sticky” as Malcolm Gladwell would put it, because of their content being smart or well assembled. They are instead pushed forward and propelled through cyberspace by hatred for a subculture of women. I say, instead of creating and sharing these hate fueled memes about whatever is the current pop culture thing you don’t understand, you instead spend more time creating memes about things you do like: poking fun at the intricacies of your favorite books, TV shows and films that you get, and think harder before laying down an easy critique of cultures you aren’t involved in.

__________________

Emma Vossen is a comics and sexuality scholar currently completing her PhD at the University of Waterloo. Her poetry is published in the upcoming Masked Mosaic anthology of fiction about Canadian comics. When she has time she writes about sex, feminism and comics at www.getsomeactioncomics.com