No.

*

*

*

*

*

*

Oh, you want to know why? Sheesh.

Part 1: 200 Years of Hate

When Noah first solicited articles for the Hatestravaganza 3000, I was delighted. At last, the Hooded Utilitarian would break its long-standing tradition of Pollyannaism and civil discourse, and vent one big collective spleen. At last, I thought to myself, this was my chance to take some cheap shots at comics like Acme Novelty Library, Love and Rockets and Maus.

Just kidding.

There’s no such thing as a cheap shot at Maus.

But what, I asked myself, would I write about for the Hatepocalypse? The brief was to write about the worst comics of all time, but what, I asked myself, were they? How, I asked myself, would I choose between them? Why, I asked myself, was I waking up in a hotel room next to a dead clown, a jar of petroleum jelly and a rubber chicken; and, while I was at it, whose vomit was that on my underpants, and why was it on the inside?

To choose the worst comic of all time — the triple-headed Lucifer at the heart of Universe Comics — I began to make the mental descent through my own personal hierarchy of comics, which goes something like this:

- Comics I really like

- Comics I like

- Comics I’m neutral about

- Comics I dislike

- Comics I hate

- Comics I hate so much that I want to throw them across the room

- Comics I hate so much that I actually have thrown them across the room

- Comics I hate so much that I want a refund

- Comics I hate so much that I want to hang around in comics stores and give refunds, out of my own pocket, to anyone else who actually buys them, as a kind of Bad Comics Fairy (which is like a thing Joe Queenan once did for people coming out of Bad Movies)

- Comics that belong to the emperor

- Comics that, at a distance, resemble flies

- Comics I hate so much that I want to punch the people that sold them to me in the face

- Comics I hate so much that I want to punch the author in the face

- Comics I hate so much that I want to punch the author, the author’s readers, the author’s publisher, the author’s reviewers, the author’s parents, the author’s grandparents, the author’s children, the author’s extended family including that creepy uncle that everyone tries not to think about, the author’s pets, the author’s friends, the author’s enemies, the author’s frenemies, the author’s enemends, the author’s past and present boyfriends and/or girlfriends, the author’s cute guy and/or gal that they have a secret crush on who works at the cafe/pub/bookshop/adult incontinence specialty store, the author’s that one guy and/or gal that they hung out with in college that in hindsight they could have hooked up with or maybe just fingerbanged/jerked off one time after they both got really drunk or at least that’s what they’d like to think even if they’re far off base and the guy and/or gal in question actually had no interest in them as such at least not that way, and, well, fuck it, I might as well punch myself for having read the thing in the first place. In the face.

Once I had mentally reached the very lowest circle, I began to look around. Perhaps the worst comic of all time was, fittingly, Daredevil: Guardian Devil (Joe Quesada, Kevin Smith et al.), a comic of such transcendentally concentrated bad that it creates its own gravity well, from which nothing can escape. (Sometimes I wonder whether I’m still trapped in there, my whole life since then one long hallucination as the black hole of Guardian Devil shittiness stretches out my dying hallucinations into infinity; reader, by the end of this essay you might know the feeling.) Or perhaps the worst comic of all time was that one over there, Nextwave (Stuart Immonen, Warren Ellis et al.) — a pandering insult not just to the reader’s intelligence, but their stupidity as well. Or, there, Jeffrey Brown’s autobio comics, a perfect pairing of style and subject-matter so inept and repulsive that I remain half-convinced that the whole exercise must be some kind of elaborate performance art parody of autobio comics.

You know, just like Marjane Satrapi.

But were these comics actually bad enough to be the worst comic of all time? How bad would they have to be to be the worst comic of all time? As I pondered these questions, there slowly, gradually, coalesced in my mind a fundamental insight:

I needed to bury that rubber chicken out in the woods, and fast.

Also, there couldn’t possibly be a worst comic of all time.

Part 2: The Hatest Show on Earth

Let’s think about what it would take for there to be a worst comic of all time.

In fact, let’s start with an even more general question — what does it take for there to be an X-est Y? For example, the smallest child, the youngest thing I’ve ever stolen candy from, the heaviest thing tied and gagged with electrical tape in the boot of my car, the entirely hypothetical example most likely to get the FBI interested in my recent activities particularly on the night of the 25th and do I recognise this rubber chicken?

At the very least, we need two things: a set of objects which we class together (the Ys) and a property we can rank them on (the X-est). For instance, we take all the children and order them by smallness, and the smallest child is…well, it’s the member of the set Y that has the most of property X.

I mean, duh.

So for there to be a worst comic of all time, we have to have two things: a set of things that we can classify as “comics” and a property we can rank them on — let’s just say it’s “badness” and agree that we’re talking specifically about aesthetic badness (as opposed to other kinds, like moral badness — and let’s also set aside the question of whether these properties are genuinely distinct).

Already several questions arise:

1) What counts as a comic?

2) Does everyone agree on what badness is when it comes to comics?

3) How do we make comparisons of badness between different works?

I will now address these questions in turn.

1) What counts as a comic?

Who cares?

2) Does everyone agree on what badness is?

No, really, who cares?

3) How do we make comparisons of badness between different works?

No, really, I’m not kidding, who cares?

In short, I can’t think of anything more boring than arguing about (1)-(3). Well, maybe re-reading The Black Dossier, but that’s a fate you shouldn’t wish on anyone, not even Jess Nevins. (2) in particular is just dire; discussing it at any length is the surest sign of a dullard and a bore.

In any case, it simply doesn’t matter how we answer (1)-(3). For even if these questions were readily settled, there still couldn’t be a worst comic of all time, for what is really a very simple reason: there is no common measure of badness for comics.

Part 3: But, really, all you need is love

Think about the myriad ways in which a comic can be bad.

It can have clumsy figurework, lazy rendering, too much rendering, no clarity of action from one panel to the next, rely on cliche, be pretentious, be too precious, be too serious, be too glib, be psychologically implausible, show inconsistent characterization, show no characterization to speak of, rely too heavily on plot coincidence, pander to its audience, talk down to its audience, assume too esoteric a knowledge base in its audience, be too cryptic, spell things out too much, be shallow, fail at its attempts to be deep, show too much contempt for its characters, show too little contempt for its characters, be too long, be too short, be unfunny but trying to be funny, be funny when trying to be tragic, wallow in suffering for its own sake, be blind to suffering, have unconvincing dialogue, have boring dialogue, have dialogue where all the characters sound the same, have art where every character looks the same, have gaping plot holes, have a confusing plot, have an internally inconsistent plot, rely on misunderstanding of e.g. science, be smug, be too convinced of its own greatness, be lazy, try too hard, be too bombastic, be too openly manipulative, fail to produce whatever mood it’s trying to achieve like e.g. an unscary horror comic, fail to make its would-be sympathetic characters be actually sympathetic, be nasty without pay off, be not nasty enough in its attempts at parody or satire, be too murky, be too garish, rely too much on swipes, use the font comic sans, no one’s reading this far right, fail to match verbal and visual content, be derivative, be whiney, be sexist, be racist, be otherwise ideologically noxious, be simple-minded, be too generic, be too stilted, rely too heavily on photo reference, rely too heavily on photoshopped effects, be boring, be too hectic, resolve its conflicts too abruptly, have characters and events act thus-and-so only because the plot demands it, be unconvincing, be parochial, be vague, be infuriating, be incompetently puzzling, show a poor understanding of light, ditto for anatomy, human emotion, the range of human body types and faces, fabric texture and everyday objects, i mean really surely everyone has given up by now, fail to direct the reader’s gaze to the relevant parts of a panel, fail to direct the reader’s gaze from one panel to another within the same page, fail to represent spatial relationships clearly, represent inconsistent spatial relationships, ditto for causal relationships, parse action poorly, show poor perspective, show indifferent framing, rely too much on verbal exposition, jesus christ you’re still here huh ten internet points for you, be too cynical, be too naive, impose an arbitrary structure, bury visual clarity beneath artistic tics, be mary-suish wish-fulfilment, be too explicit for the intended age group, be unexciting in action sequences, be stupid, be twee, be sloppy, be visually drab, be overladen with text, be Before Watchmen, have poorly placed word balloons and, uh, so on.

I mean, I’m not a negative guy, you know? But that seems to me like a lot of ways a comic can go wrong.

Part 4: Lo, there shall cometh an Avenger

And I’ve barely even started.

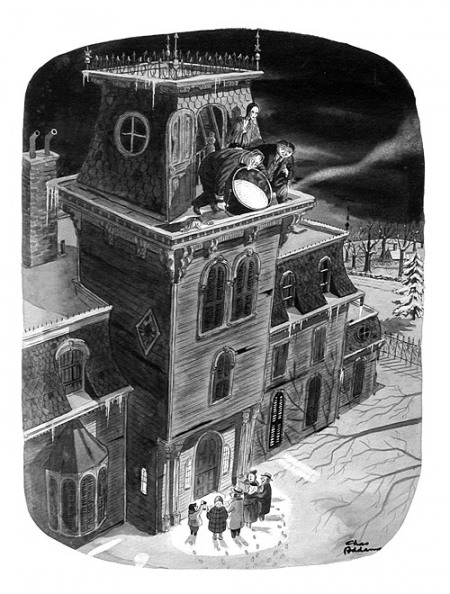

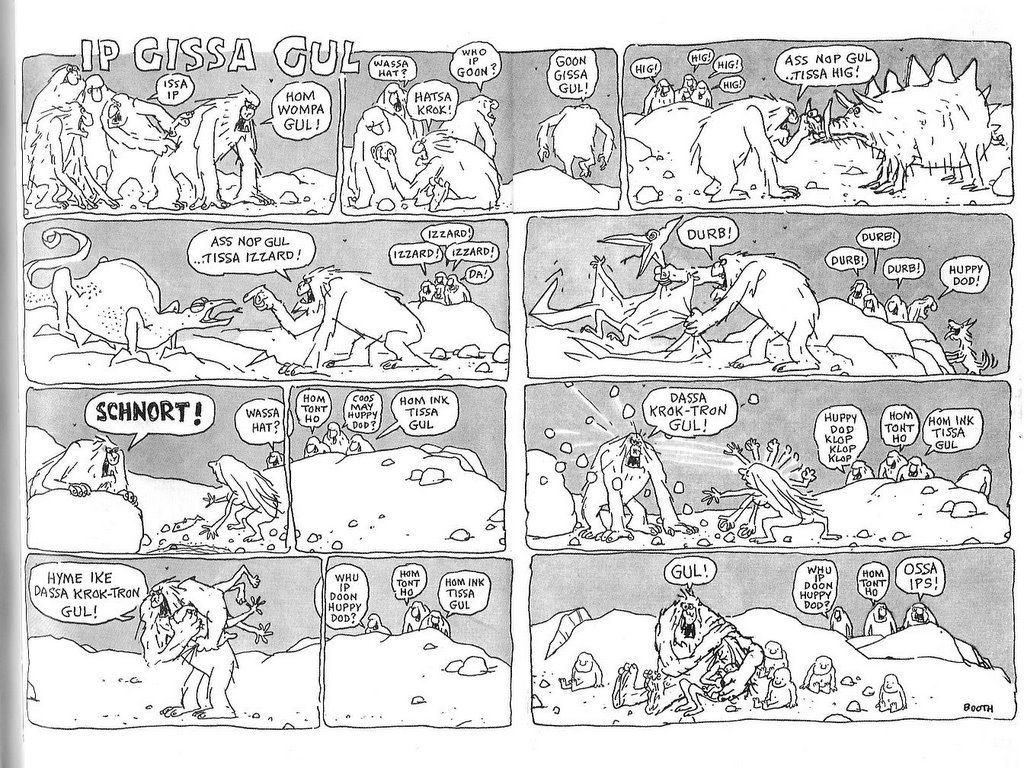

But people probably don’t want to hear all that negativity, yeah? Or, at least, they don’t want to read me blather on about it any more than they wanted to read my epic seventeen-part pitch to expand the Marvel Cinematic Universe franchise with a West Coast Avengers spinoff featuring these guys as villains:

As is well known, Parts One through to Sixteen of this series detail my plans for the solo films building up to The Walt Disney Company’s Marvel Entertainment’s The West Coast Avengers, showcasing the characters with most multi-platform crossover potential, viz. Wonder Man, Tigra and Jumpsuit Doctor Pym. In Part Seventeen, I turn to the main event, my spec script for The Walt Disney Company’s Marvel Entertainment’s The West Coast Avengers: we start with a flashforward to a future after the West Coast Avengers have disbanded!!! Tigra, Wonder Man, Jumpsuit Doctor Pym and new-in-this-film USAgent each finds themselves in a dark place, a place where they need to reconnect with what it means to be a West Coast Avenger. What could have disassembled The West Coast of the North American Continent’s Mightiest Heroes?! Flashback to the present! Big Sur is restless — the region stirs, unsettled by dark rumours of a sinister underground army! The police find a mutilated corpse in the sewers, pincushioned with cactus needles! At a trailer park on the edge of town, a pair of tourists run in from the desert, half-crazed and babbling about a giant monster lizard! Senior citizens start collapsing from heat exhaustion! There’s some sinister happening or other to do with an isolated hill, like someone falls down and breaks their crown or something! The authorities haven’t got a hope of dealing with this new breed of criminal — the only one who can is a brilliant yet devastatingly handsome blogger named Rick Jones, one of the Jones boys, who sends out a message on his ham radio universally beloved blog for anybody who can help defeat the creatures the media have dubbed the Desert Horrors

— but I digress. Suffice it to say: there are lots of ways a comic can go wrong in the “writing”, and a lot of ways in the “art”, and a lot more ways when you put those two things together. SYNERGY!

What I claim is that the ways a comic can be bad are irreducibly plural and literally incommensurable — there is no way to put all these different ways together so that you end up with a single dimension of badness (which, if you recall, is what we need in order to declare something the X-est Y, in this case the worst comic of all time).

Before I discuss this in more detail just what this means, however, it’s first worth considering whether badness is indeed irreducibly plural. The list I rattled off above is some evidence, but perhaps not conclusive; the fact that there are a whole bunch of different phrases in the vicinity doesn’t mean that they don’t all point to, in one way or another, the same property. In much the same way, I could use a whole bunch of different descriptions to refer to the same person, for instance, “former He-Man scripter”, “loathsome“, “hack”, or sociopath” — all of which describe the one man, J. Michael Straczynski.

Interlude: Two Minutes Hate

Now, the last time someone described that guy as a former He-Man scripter, parts of the comicsoblogosphere clutched at their pearls that anyone would have the temerity to to take a “cheap shot” at J. Michael Straczynski, the universally acclaimed and highly respected author of After Marvelman Supreme Power and those two issues of Superman and Wonder Woman before he quit.

To which I say: J. Michael Straczynski deserves every cheap shot you can throw at him. J. Michael Straczynski is so ugly that, when he was born, the doctor slapped his mother. J. Michael Straczynski is so fat that, when he sits around the house, he sits around the house. J. Michael Straczynski is writing some of the prequels to Watchmen.

Actually, that last one is a low blow. I apologise.

But maybe the original author of that quote was actually trying to be nice. Maybe he thought “He-Man scripter” was the nicest thing he could say about J. Michael Straczynski because, let’s face it, that probably is the most charitable reading of the dude’s entire career. Anyway, to chide someone for mentioning J. Michael Straczynski’s early career as He-Man scripter is like chiding someone for mentioning Hitler’s early career as Mein Kampf writer: it’s not that they’re being unkind, it’s that they’re not being unkind enough.

YES INTERNET I JUST COMPARED J. MICHAEL STRACZYNSKI TO HITLER.

YES I AM SAYING THAT WRITING MANY SHITTY COMICS AND BEING A PLAGIARIST AND A SCAB IS EXACTLY AS BAD AS BEING CHIEF ARCHITECT OF GENOCIDE

YES EXACTLY

PLUS I HAVE IT ON GOOD AUTHORITY THAT HE DOESN’T LIKE KITTENS

I know that, by the Official Rules of the Internet, invoking a comparison with Hitler means that I’ve “lost the argument“.

But, on the other hand, I want you to consider this:

Go fuck yourself

(BTW, I’m not hyperbolising about his sociopathy. Take a look at the ICD-10 criteria for sociopathy and, if you’ve followed his career and public statements over the last few years, you’ll see that J. Michael Straczynski scores at least a 5 out of 6)

Part 5: In Which I Run Out Of Jokes And Resort To Straight-Out Philosophy Instead, Or, If You Prefer, “Philosophy”, And, Let’s Be Honest, “Jokes”, Too

As I was saying, the fact that I can use a bunch of different descriptions for what makes a comic bad doesn’t mean that there are that correspondingly many different types of badness. Couldn’t there be fundamentally just one type of badness manifested in different ways? For some of the items on the list are obviously related and can be “reduced” to a more fundamental vice — e.g. relying on cliche and being derivative might be reduced to a more basic lack of originality. So mightn’t we go further and discover a single kind of badness underpinning all the buzzing, blooming confusion of suckitude — and, if so, wouldn’t we then be able to point to the comic with the most of that as being the worst comic of all time?

I’ll consider — and I’m not kidding this time — two candidates for rock-bottom badness. You can skim this if you want; it gets a bit technical in places. I’LL STILL RESPECT YOU.

i) Failure to achieve the effects the creator was aiming for

A first thought might be that what makes an artwork bad is that it fails to do whatever the artist wanted it to do. For instance, Alan Moore wanted the metaphysical discussions in Promethea to be gobbledegood, not gobbledegook, but, well, you know how that turned out (personally, whenever I hear the word “quantum” from anyone but a physicist, I reach for my revolver). Al Capp wanted his Li’l Abner strips to wittily satirise social folly well into the 60s and 70s. Alex Ross wants not to suck. On such an account, then, the worst comic of all time would simply be the one that failed most to achieve the effects the creator was aiming for.

That’s a first thought. A second thought might be that the first thought is stupid. Isn’t it obvious that an artwork can be great even for reasons unintended by its creator? Indeed, isn’t it obvious that sometimes an artwork can be great in spite of the creator’s intentions, can be great precisely to the extent that its creator’s intentions go unfulfilled? One of the things that makes Cerebus such an intriguing work, for instance, is the way it diverges from the stated aims of Dave Sim, often so far as to fulfil the very opposite of those aims; there are large chunks of Cerebus that succeed in spite of what Sim wants them to do. (This is not to slight Gerhard’s important role as co-creator — indeed, if we think about collaborations, we quickly see another reason that aesthetic quality couldn’t depend on fulfilling creators’ intentions, viz. that those intentions might well conflict in a collaborative work).

And there’s an even deeper problem with this suggestion, which is that it leaves entirely mysterious a central fact about how audiences respond to art: the fact that, in general, audiences don’t like bad art, or at least art that they take to be bad by their lights. Add a million caveats to that claim, or as many as you please — but it’s still a truism that, to at least some degree, bad art is, you know, bad. But why should audiences care about whether artists fulfil their intent — and, in particular, why should it be a good thing when they do, and a bad thing when they don’t, and why should our appreciation of the work follow suit?

One last point in passing: to rest our assessment of an artwork on the creator’s intentions is to commit the Intentional Fallacy, which is totally a fallacy for very good reasons and not just because I read on the internet that a couple of literary critics said so in the 40s, but I’m not going to go into the very good reasons here because hey look behind you is that a three-headed monkey?

ii)We just don’t like it

Here’s a different approach. So far we’ve been proceeding as if aesthetic goodness and badness are in some important sense mind-independent, as if there are objective facts of the matter here. But it’s just as plausible — indeed, perhaps even more so — that they are fundamentally based on our reactions to art, that all the different aesthetic failings I briefly listed, and the many others unlisted, are a matter of how we feel about various artworks. We can call this view aesthetic subjectivism.

Aesthetic subjectivism by itself does not entail a common measure of badness, however; it might still be that there are lots and lots of different subjective types of badness (just as there appear to be irreducibly many secondary properties which are each, nonetheless, subjective — and if that read like gibberish to you, don’t worry, it’s not important). So we would need to go further and suppose, not just that aesthetic badness is based on how we react to art, but that it can be simply boiled down to how much we dislike it. On such a theory, the list of vices above would merely be different ways of expressing the fact that we don’t like it.

If this were right, then the worst comic of all time would simply be the most disliked comic of all time. But there are problems here, too.

For a start, for all of the terrible, horrible, no good comics we have individually read, there are another hundred comics that are even worse, and another hundred that are even worse than that, and then there’s Paradise X. But, except for lunatics and sex perverts, most people don’t go out of their way to read comics that they think are going to be terrible, so there’s an inbuilt problem with trying to find the most disliked comic of all time: it may well not be the most dislikeable comic of all time.

So, all right, let’s make it dispositional: a bad comic is one that people would dislike, and the worst comic of all time is the one that people would dislike the most.

This does not get us out of trouble, however, for any comic is potentially dislikeable, under the right — or the wrong — circumstances. If you read a comic while distracted, or in a bad mood, or drunk, or sleep-deprived, you may have a worse opinion of it than otherwise; should we therefore call that comic bad, simply because people would dislike it in certain circumstances? Surely not. So we need to rule out those kinds of circumstances somehow, by saying that a bad comic is one that people would dislike under ideal circumstances, and the worst comic of all time is the one that people would dislike the most under ideal circumstances.

Here’s the question: which are the ideal circumstances? Because I’ve already tested everyone’s patience too long, I’m just going to make a bald assertion here (which we can hash out in the comments if anyone really, really, really, really wants to). There is no stable, principled way to specify ideal circumstances that does not beg one question or another — for instance, that has a good reason to discount the distaste of Nazis for “degenerate” art, or to favour dispassionate enjoyment of art over enjoyment in altered states of consciousness.

(Even more technical aside: there is a further, famous problem with aggregating individual preferences into a community-wide ranking, a problem which is known as Arrow’s impossibility theorem. I suspect this theorem scotches any hope of singling out any single comic as the most dislikeable of all time, but I don’t know enough about decision theory to be sure that the theorem is relevant here).

This does seem, I admit, to be the weakest part of my case, but, oh hey look behind you there’s that three-headed monkey again

…

and so, as I just conclusively proved while you were looking behind you, we can’t “reduce” the worst comic of all time to merely the most disliked comic of all time. Sorry you missed it; it was an awesome proof.

Part 6: The moral of the story

All right. Aesthetic badness is irreducibly plural and incommensurable. So what? So, basically, there is no way to rank all the comics along a single dimension of badness, and thus there is no way to single out any particular comic as the worst of all time.

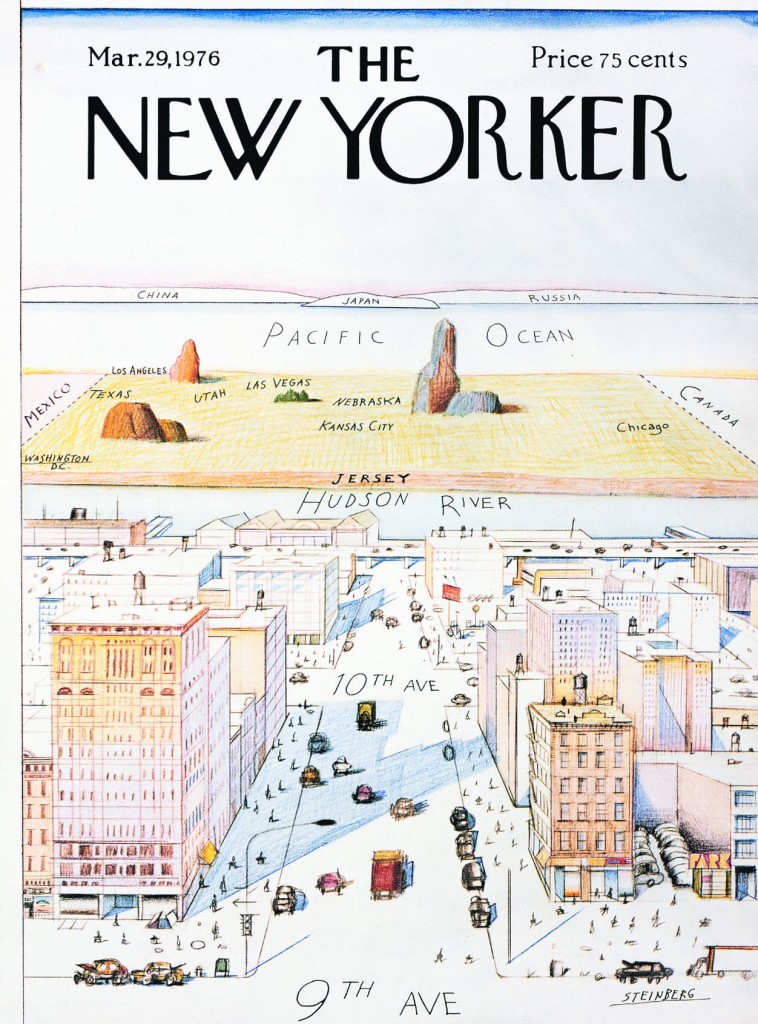

Here’s an analogy. Suppose you’re in Palomar, and you’re thinking about where other cities and towns are in relation to you — Central City, let’s say, is 4 miles to the east and 3 to the north; and Keystone City is 6 miles to the south and 8 miles to the east. (A less lazy author might have provided a diagram here) . We can represent the locations of these cities, and anywhere else on the surface of the Earth, in a two-dimensional space with Palomar at the origin, one axis for the east-west dimension and the other for north-south. Although these are two different spatial dimensions, they are commensurable — in that one mile along the east-west axis is just as far as one mile along the north-south axis. We can thus construct from these two dimensions a separate single line representing total distance from Palomar. Central City is (if I’ve done my Pythagorean sums right) 5 miles along that line and Keystone City is 10 miles along. Thus Keystone City is further away from Palomar than Central City and, if these were the only cities on the planet, we could say that Keystone is the furthest city from Palomar.

Now imagine aesthetic space as a massively multi-dimensional space, with as many axes as there are different types of aesthetic badness. For instance, we might have one axis representing lack of spatial clarity, another representing implausible characterisation, another representing being written by Brian Michael Bendis, and so on. If I’m right that the different types of aesthetic badness are incommensurable, then there is no way to do anything similar for aesthetic badness.

Suppose we’re comparing just two comics, (say) Judgment Day and Blue Monday. Let’s suppose that we can all agree that Judgement Day is worse than Blue Monday at spatial clarity (i.e. showing where characters are standing in a room, what their sight lines are, and so on). This would mean that Judgment Day was further along the axis for spatial unclarity than Blue Monday. Let’s also make things super-easy and suppose that we had some unproblematic way to quantify this dimension, so that (say) Judgment Day has a spatial unclarity rating of 17, and Blue Monday a rating of 5

So far, so good. It’s easy enough to compare comics along a single dimension. And let’s also suppose that we can say that Blue Monday is more derivative than Judgment Day, which means that Blue Monday is further along the axis of being derivative. Again, so far, so good. And, again, suppose there’s some unproblematic way to quantify derivative-hood, so that Blue Monday has 7 units of derivative-hood and Judgment Day only 1.

Now here’s the kicker: how do we then put those two dimensions together to say which comic is worse overall? Is it worse to be spatially unclear or to be derivative? How many units of derivative-hood are equivalent to one unit of spatial unclarity? And once we consider all other the dimensions of aesthetic badness beyond just these two, the problem explodes in complexity. Is it worse to be politically obnoxious to this degree, or murkily reproduced to that degree? Is it worse to pander this much or be that much reliant on dei ex machina? Is it worse to be a Sal Buscema Marvel comic from the 70s or a random daily episode of Cathy?

It’s crucial to realise that my point here is metaphysical, not epistemological. It’s not just that there’s no way to find out the answer, it’s that there is no answer to find out. There simply is no fact of the matter about how to compare all these different aesthetic dimensions, and so there is no fact of the matter about what is the worst comic of all time. There is no worst comic of all time.

Asking what is the worst comic of all time is like asking what is the worst sentence of all time, or the worst sandwich of all time. Is it a sandwich made from moldy bread and expired meat product? Is a rock the worst sandwich of all time? Is it a sandwich that gives you AIDS? Is it a poop sandwich? Is it a sandwich made by Hitler? Is it a poop sandwich made by Hitler? There is no worst sandwich of all time, because there are too many ways for a sandwich to be bad, and there is no worst comic of all time.

But if there was, J. Michael Straczynski would have written it.

PS: While we’re in the festive spirit, a big fuck-you to all the overrated, shitty comics I’ve ever read in the vain hope that they’d be better than they turned out to be. Fuck you, Guardian Devil, Nextwave and Jeffrey Brown. Fuck you, Kingdom Come. Fuck you, Aqua Leung. Fuck you, League of Extraordinary Gentlemen. Fuck you, Walking Dead. Fuck you, Scalped. Fuck you, Y the Last Man. Fuck you, Transmetropolitan. Fuck you, Invincible Iron Fist. Fuck you, One Piece. Fuck you, Sin City. Fuck you, Doctor 13 and the Architecture of Mortality. Fuck you, Final Crisis. Fuck you, every Batman story Grant Morrison has written. Fuck you, The Invisibles. Fuck you, New Frontier. Fuck you, A Drifting Life. Fuck you, In the Shadow of No Towers.

Fuck you, Umbrella fucking Academy.

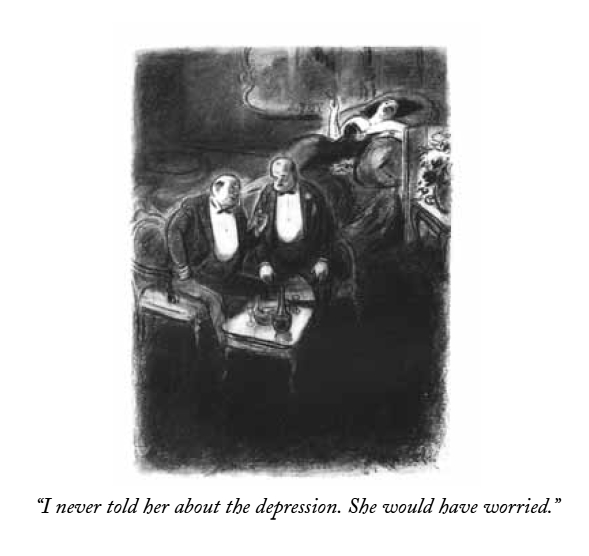

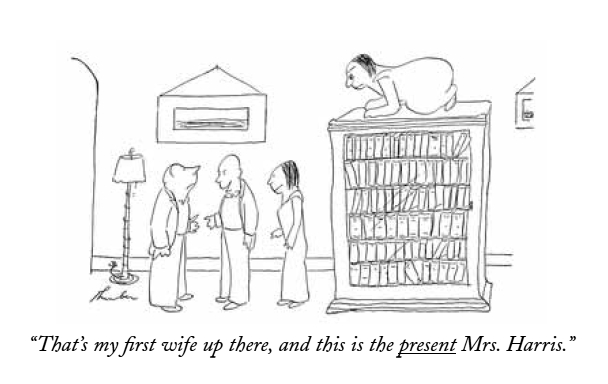

Image attribution: Images of comic critic — Dan Clowes, Eightball #3; Desert Dwellers — Al Milgrom, Joe Sinnott, Ken Feduniewicz, Janice Chiang and Steve Englehart, West Coast Avengers #17 (I think), scan taken from here; “it’s stupid” — James Kochalka, scan taken from here, don’t know where it was originally published.

__________

Click here for the Anniversary Index of Hate.