I started ingesting Jaime’s work through osmosis when I was a little kid hanging out in the back of my father’s comic book store — images in ads, articles, seeing the covers of his books on shelves, hearing conversations about Maggie and Hopey. Love and Rockets was an aesthetic space that existed for me in the abstract long before I ever read the comics themselves. (In one sense, that adds a layer of truth to Noah’s assertions re: nostalgia, in that the Locas stories all bring me a nostalgia for the mysterious allure they exerted on my young mind before I’d read them. I get wistful just looking at their cover fonts!)

Despite being around Love and Rockets comics since an early age, I didn’t read any of it until much, much later, and I didn’t start at the beginning. The first comic by Jaime Hernandez I ever read was “Flies on the Ceiling,” which still ranks among the most astonishing comics works I’ve ever laid eyes on.

Most of the elements that make Jaime one of my favorite cartoonists are present in “Flies on the Ceiling”:

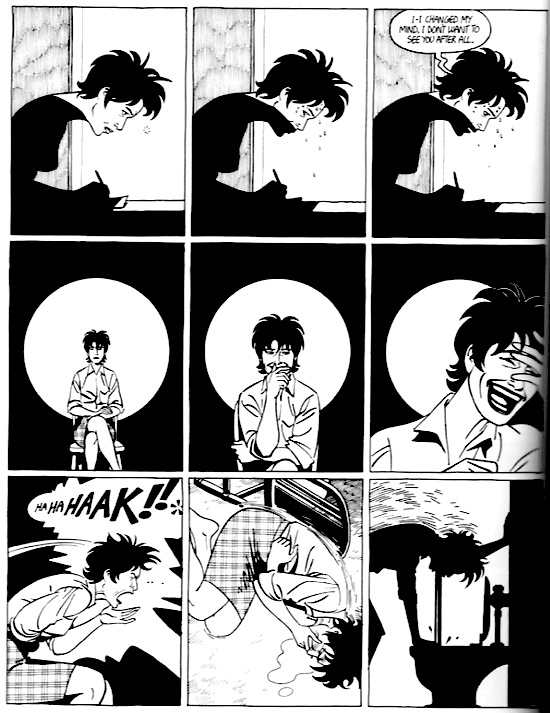

– the achingly beautiful drawings that find the perfect mixture of realism and cartooniness, seemingly effortless in pulling from the best of both worlds

– the breathtakingly controlled compositions, with their deep blacks and bright whites, attention to both diegetic space and abstract negative space to create enviromental

verisimilitude and broad visual dialectics at the same time

– the ability to draw the most nuanced facial expressions in the history of comics, and to know exactly when to give them up for broad caricature

And, above all: the gaps.

Reading a Jaime comic brings to mind the old cliche about listening to Jazz – “It’s not about the notes they play, it’s about the notes they DON’T play.” Jaime’s work is full of sudden narrative gaps – abrupt jump cuts and unexplained transitions that, for me, are the most exciting element of the reading experience. I get a rush whenever my brain has to reconcile two disparate moments next to each other on the page. This page from “Flies on the Ceiling” is one my favorite comics pages of all time:

There’s another kind of exciting narrative gap in Jaime’s work, which has most recently been cited as the cartoonist’s greatest flaw by Robert Stanley Martin in his essay for the roundtable: the persistent referencing of past or future events between Locas stories.

As I said, my first Locas story was “Flies on the Ceiling,” which coincidentally Martin uses as his prime example of what he thinks doesn’t work in Hernandez’s stuff. Rather witheringly, he writes, “as anyone who’s been around a Trekkie knows, fannish types place particular value on details and resonances that casual audiences either miss or don’t understand. It’s sad that Hernandez, with all his talent, undercuts his work by catering to this proclivity at a larger readership’s expense.”

Now, I don’t know that I’m a casual audience (though my gut suggests I may qualify as a large readership), but I do know this: when I first read “Flies,” I could absolutely tell that there were details and resonances that I wasn’t fully understanding – and I considered that a feature, rather than a bug. There was already so much to tease out of the dense and fragmented structure of the story that it made perfect sense to me to also have to ponder after unexplained history. I enjoyed the friction of the unknown.

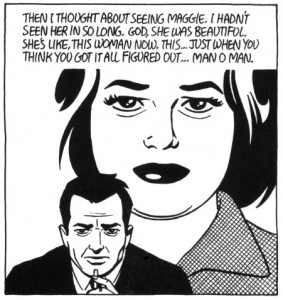

Similarly, and maybe more pertinent to the Locas stories as a whole (“Flies on the Ceiling” being in many ways a stylistic outlier), I read “Ninety-Three Million Miles from the Sun” with only a cursory non-textual idea of who Maggie and Hopey were, and no familiarity with any of the other characters aside from seeing the covers to some of the Penny Century comics. And I loved it – maybe as much for what I was missing as for what was there. The vibrancy of the characters and the visual mastery of the art was complemented by the vast ocean of story that appeared to float just beyond my reach, hinted at throughout but never fully explained.

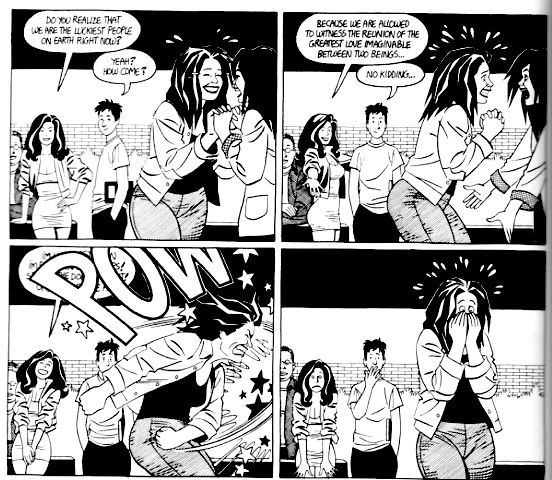

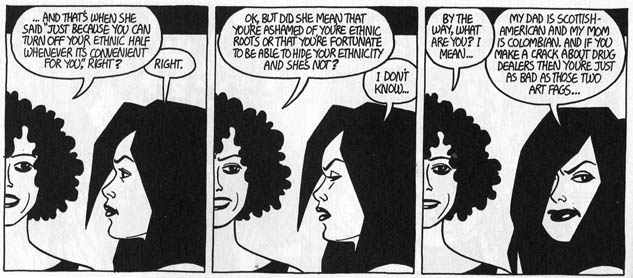

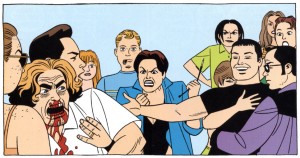

And let me be clear: I’m not saying that I was excited because I knew there was a huge backstory that I could eventually catch up on. I was excited by the suggested existence of backstory that as far as I was concerned may or may not actually exist as drawn stories. What I respond to the most in Jaime’s work is the gap between the captured moment and the suggested context. This sequence from “Ninety-Three Million Miles” (this is the entire sequence, by the way – an example of Jaime’s abrupt cutting) encapsulates everything I love about Jaime’s work not already on display in the earlier page from “Flies.” The mixture of realism and cartoon tropes, the chaotic, fun, and funny relationships between characters, and the embedding of this moment in an unseen narrative context.

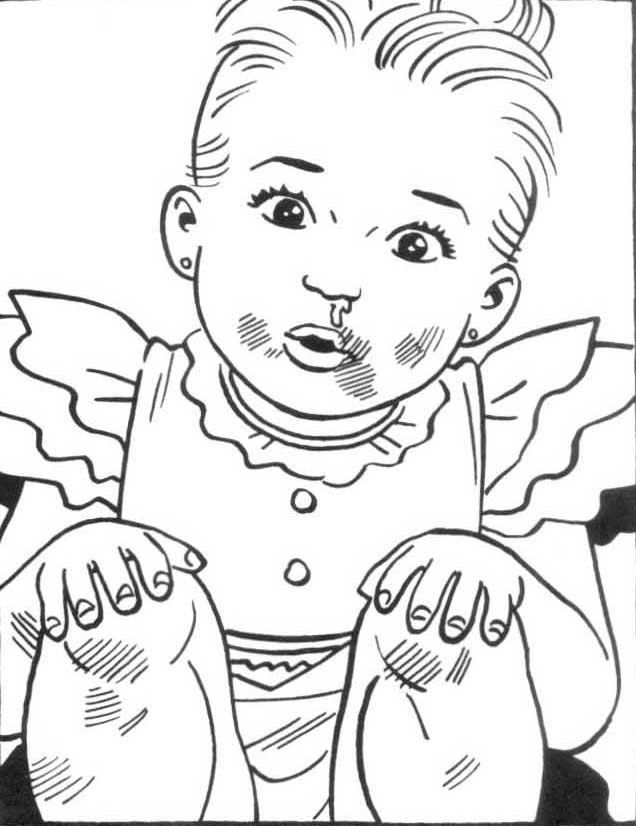

Even now, having read most of his work, there are still beautiful absences in the narrative understanding Jaime offers. One is the strange genre territory the Locas universe sits in, where someone like H.R. Costigan can exist alongside Ray Dominguez, where there can be rocket ships and super heroes and a mansion with 1000 rooms, and also the streets of Hoppers. Another is that, despite a voluminous body of work, Jaime has yet to exhaust the pasts or futures of his characters – witness the pairing of “Browntown” and “The Love Bunglers,” or the Lil’ Hopey sections embedded in “The Education of Hopey Glass” (the next book I read after “Ninety-Three Million Miles,” if you want to further chart the perversity of my Hernandez timeline). There are still things we can wonder after.

In theory, I understand that the continuity and references might keep some people from enjoying the work because they think that they’re missing something. But in practice, I have a hard time really accepting that as a legitimate complaint about LOCAS. For me, Jaime’s work isn’t a continuous narrative to be ingested in order and “properly understood.” It’s a web of moments, interconnected but not interdependent. Noah’s right in his article on nostalgia that “simply knowing there’s a whole is itself a delight,” but I think he misses (or simply disagrees) that the moments themselves are also a delight, and that the moments exist in a constant tension with the unseen whole that provides something more than merely nostalgia.

I think part of the reason Jaime’s work functions this way for me is the much-ballyhooed “realism” of his characters. I’ve lost track of what everyone means by “real” or “authentic” in these discussions, so to clarify: I mean that the characters in LOCAS exhibit an emotional verisimilitude that convinces me above and beyond suspension of disbelief for the purposes of a story that they “exist” in some way. Jaime’s mastery of body language and facial expression is part of it, as is his finding that sweet spot between specific realistic draftsmanship and universal cartoonish simplicity. But it’s also in the way his characters act towards one another, the way they speak in the sometimes-clunky but always genuine dialogue. There’s no good way to put it that doesn’t sound fannish or essentialist, but Jaime’s characters just convince me. So much so that in any given moment of a Hernandez comic, I feel as if I’m stealing a glimpse of a fully formed reality, the rest of which is just concealed from view.

(I know Caro has asked, rhetorically, why “real” should count as an inherent positive quality of a fictional character when we are all surrounded by actually real people who would be more deserving of our attention if what we’re looking for is emotional verisimilitude. To me, this is a false equivalency. A person is a person and a character is a character. I don’t watch my friends and family with an omnipotent eye for my own entertainment. There are inherent responsibilities and detachments, different empathies that come into play, interacting with a fellow real human being. The purpose of a “real” character isn’t to supplant real life, but to reflect it, offering you a way of experiencing and thinking about people that actual people can’t ever supply. Conversely, real people offer experiences that fiction can never supply. That’s why we need BOTH.)

(I also don’t quite understand or believe Caro’s comment that “Emotional verisimilitude and compelling characters and being real are just the bare minimum I expect of competent fiction. It’s not what gets you praised; it’s what gets you published.” There’s a difference between a character being well realized enough for you to go along with a story; another for you to be truly convinced of the character’s inner life. If the latter is really as ubiquitous as she seems to imply, then she exists in a literary universe I am unfamiliar with.)

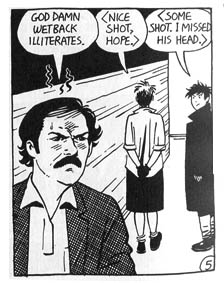

Lastly (and this is a point too important to bury at the end of an overly long and discombobulated essay, but here I go anyway) Jaime’s work sends me because I have an inherent love for the aesthetic of comics themselves, and his comics exalt those aesthetics. This is a position our host tends to disagree with – it seems (and Noah, please correct me) that he places more value on plot and character choices independent of form than on the ways in which formal choices craft plot and character. I camp out on the opposite side of that formulation. For example, in his Jaime essay, Noah called attention to this two-panel sequence in order to say of it, “You see Maggie from a distance, and then in close up. It’s not an especially interesting or involving visual sequence…”

Whereas, to me, there’s a wealth of information in these two panels. In the first panel, Calvin is standing between the young kids and the young adults. He’s clearly apart from both, but he’s turning away from youth and facing a sexually fraught tableau – his blossoming older sister flirting with his rapist. The dark shadows on the underside of the tree make the scene in the distance forbidding but also contrasts with and then highlights the two figures below. The second panel is dramatic not for its shifting perspective, and not for the readers seeing Maggie as post-pubescent for the first time (as Noah posits), but for Calvin seeing his sister as a complex and somewhat frightening part of a world he doesn’t understand but which causes him pain and humiliation. It’s Calvin seeing the laughter in her eyes next to the older boy, and it’s the dismissiveness of her words cast against Calvin’s confused feelings of jealousy and protectiveness towards her. These are all present in the form itself, and are inseperable from the content.

The greatness of Jaime’s characters and storytelling has as much to do with the way his drawings exist on the page as with the particulars of his plots. To me, there is joyful aesthetic purpose in characters existing inside stark black-and-white fields, in characters existing simultaneously as realistic and cartoonish, and in the composition and arrangement of images on a page to create a sense of movement and life. These elements are just as much a part of “who” these characters “are” as their actions within the plots they inhabit. Just spending time with these drawings – with these characters (same thing) – is enough for me to say that Jaime is one of the best.

___________

The index to the Locas Roundtable is here.