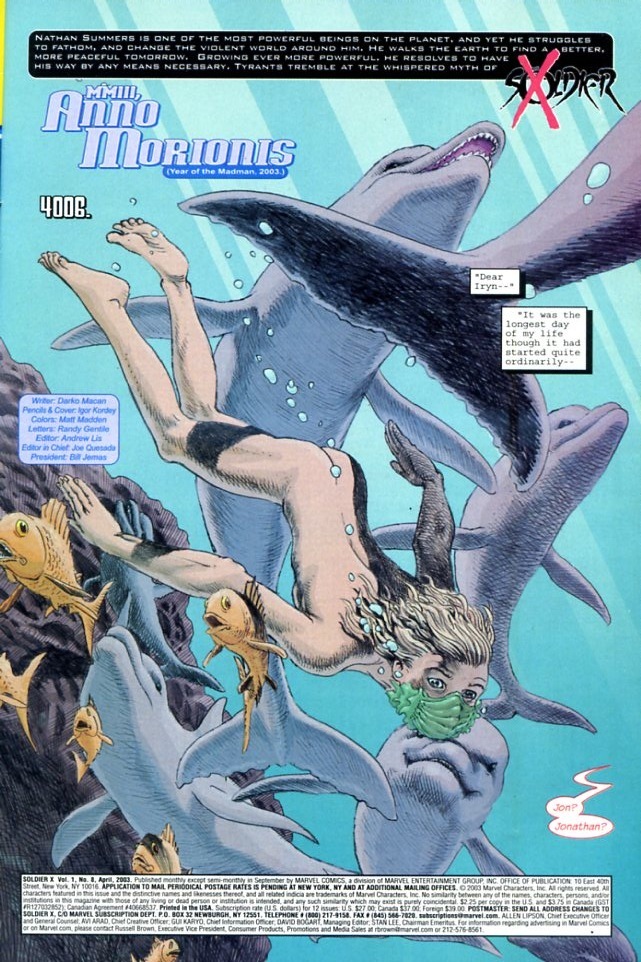

To finish up our Cable/Soldier X blogathon (here and here) Tucker and I harnessed the power of the internets for one of those virtual chats all the kids are talking about. Our conversation is below.

________________________________

STONE: So, I was trying to remember why it was we ended up doing a back-and-forth on these particular issues, and while I’m sure I could resort to searching my email, I think I’ll just take a guess and see if I’m right: you and I got tired of going back and forth and not feeling excited about the possibilities we were throwing at each other, and our exhaustion timed out around the same time that I suggested Cable/Soldier X. Does that sound right?

NB: Yes, I think that’s right. And so I ask you…why did you suggest these? Was it Jog’s discussion of them that inspired you? I know I’d never heard of them…and indeed, barely knew who Cable was. I had pretty much completely stopped paying attention to Marvel by the 90s, and certainly by the early 2000s when this came out.

STONE: It was a couple of things that put these on my radar. I don’t know which came first in my reading, but Jog had written about these comics for Savage Critics, and Sean Collins had written about them for Robot 6. (Marc Oliver Frisch had also mentioned them as well.) Another thing that made these interesting to me was that I had met a cartoonist–I’m not sure who, I think he’s a Spider-Man person, one of those people who drew it when it was coming out on a weekly basis–who drunkenly rambled about how Cable was “the perfect character” for a full 15 minutes one night at a party. It wasn’t a totally cogent argument, but it made an impression on me–like you came to realize, Cable isn’t that interesting of a character when you actually read Cable comics. The final thing, although this came up after we’d agreed to write about these, was a general curiosity about this “nu Marvel” time period, where Marvel was publishing oddball creative teams and seemingly letting people do whatever they’d like. I wasn’t reading comics during that time period, so it’s a total blind spot. I know a few people who don’t normally get into super-hero comics talk about that period fondly, and it’s got a bit of novelty because of that.

Also–I read some Cable comics a couple of years ago, and I actually enjoyed them. They were artistically all over the place–sometimes it would be Paul Gulacy, sometimes it would be Jaime McKelvie, and other times it was Ariel Olivetti–but it was a grindy, strange comic that didn’t seem to have any “importance” to it, and I seem to appreciate that a lot more nowadays than I do a comic that wants to be important and tries to make that clear on every other page.

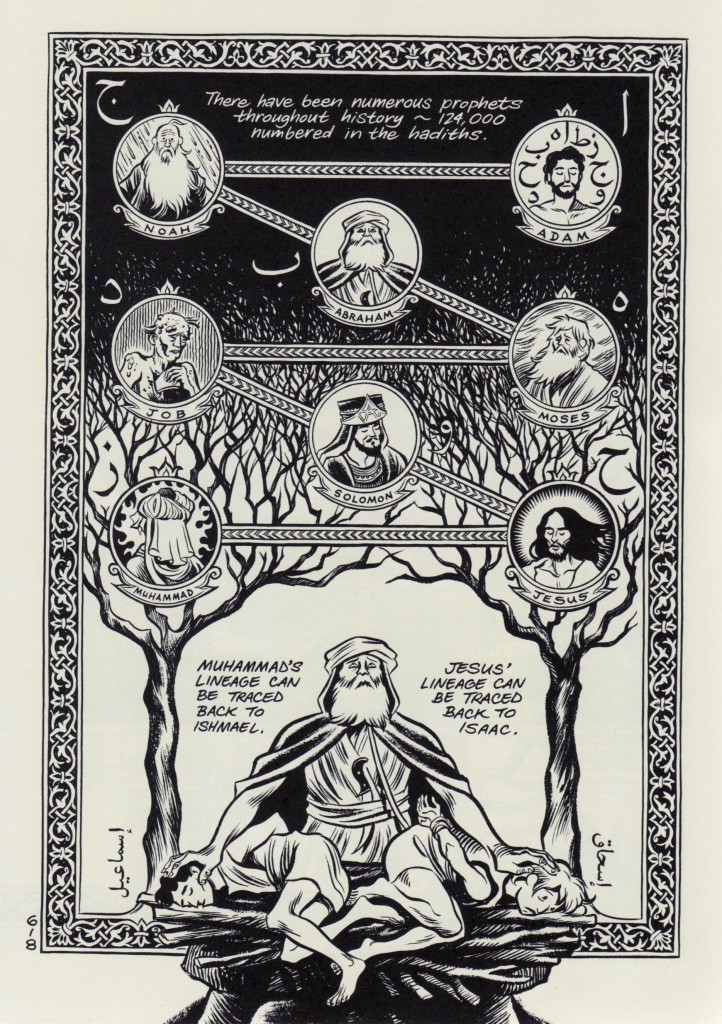

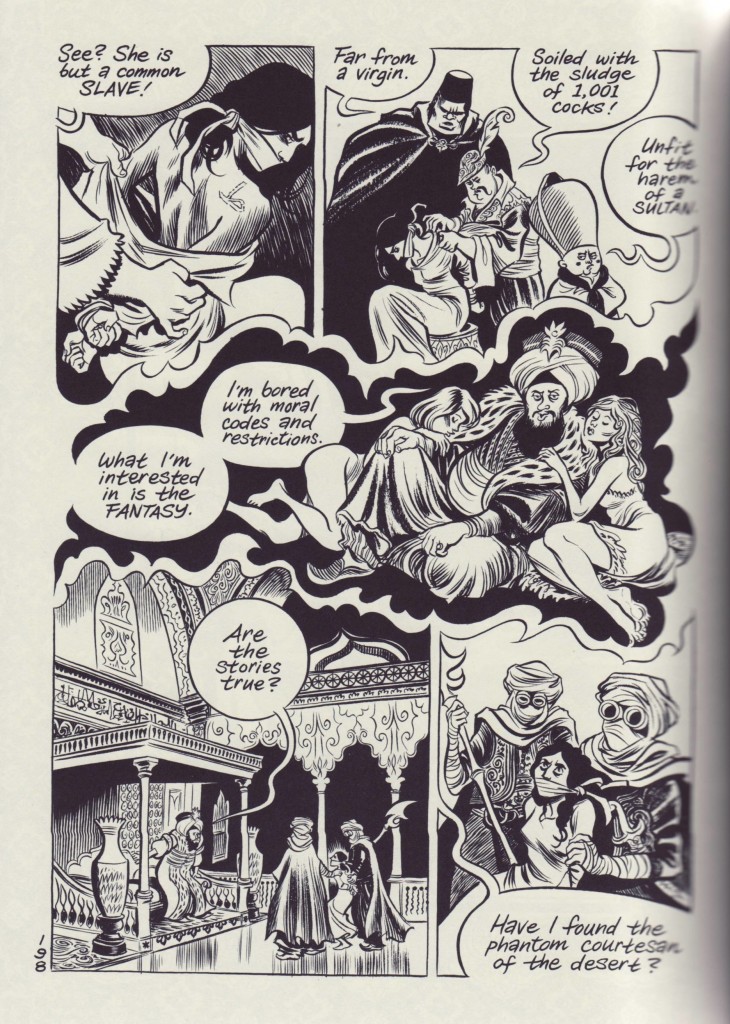

Paul Gulacy art for Cable

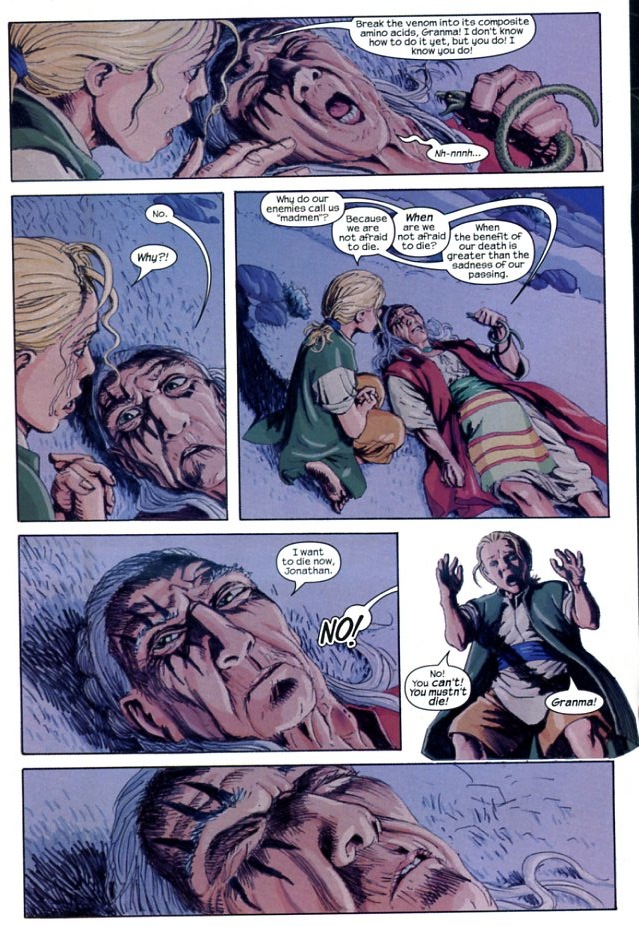

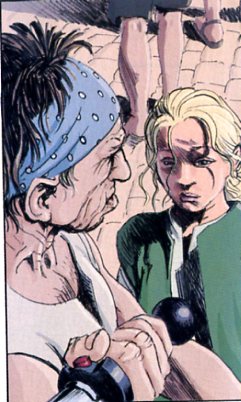

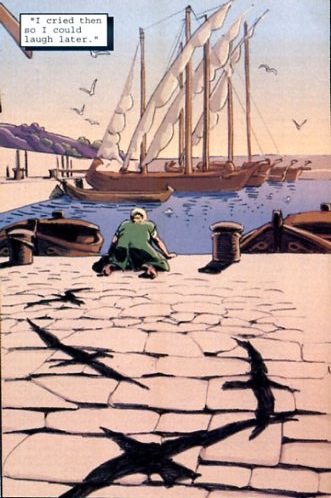

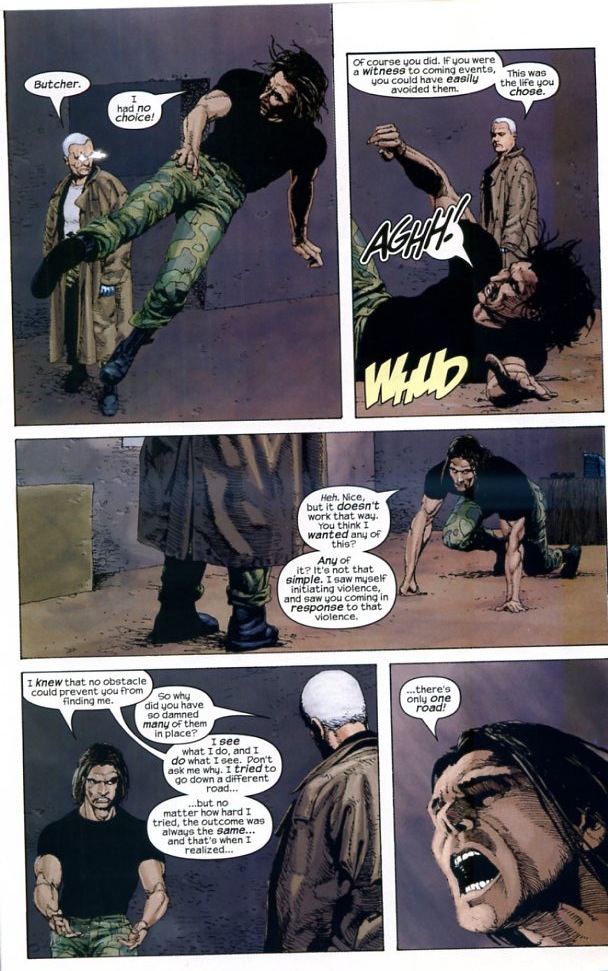

I know you didn’t really like these comics that much, but I was hoping you might be able to expand a bit more on the differences between the Kordey/Macan/Lis issues and what came after. Those last four issues are, as you noticed, fucking horrible–but they’re a lot more like what Marvel usually publishes.

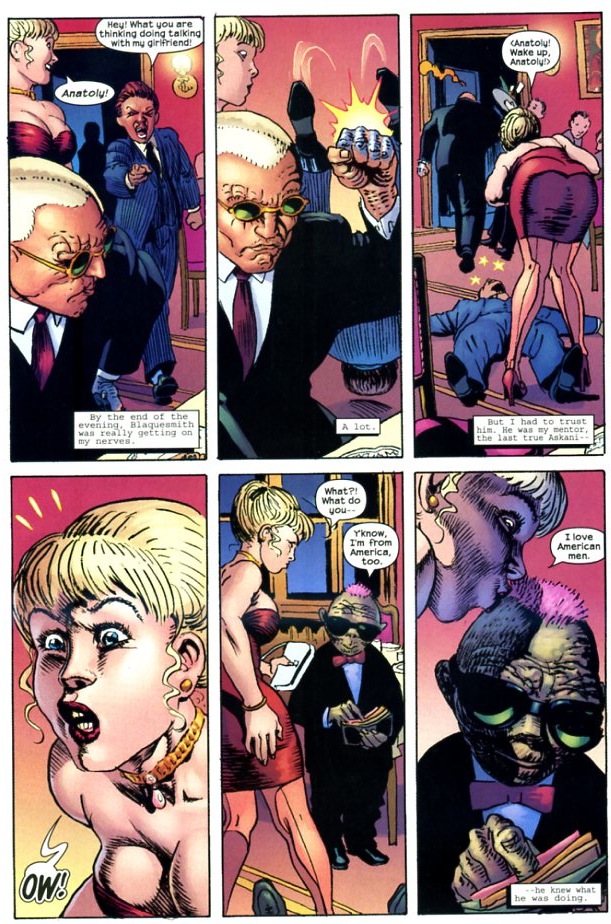

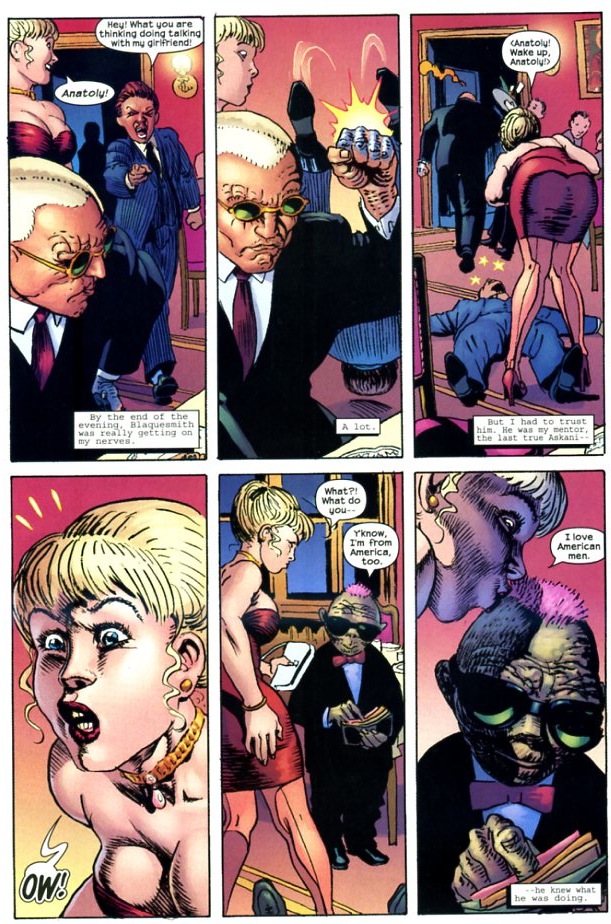

NB: Yeah; I didn’t hate the Macan/Kordey issues, thought it’s clear you were much more taken with them. Kordey is an interesting artist; not spectacular, or anything, but I like his bent for caricature and the enjoyment he takes in drawing weird stuff — he clearly had a lot of fun with Blaqu-whatever-his-name-was. And I appreciate his cheesecake too; he likes the women with the curves and sensuous street clothes. Compared to Power Girl’s boob window or super-proportioned bimbos in skintight nonsense and unsensible shoes, it’s really a relief to see just garden variety lascivious male-gaze with some mild suggestions of dwarf-porn. You feel like Kordey has probably met actual women on occasion, and maybe even had some sort of relationship with one. It’s refreshing.

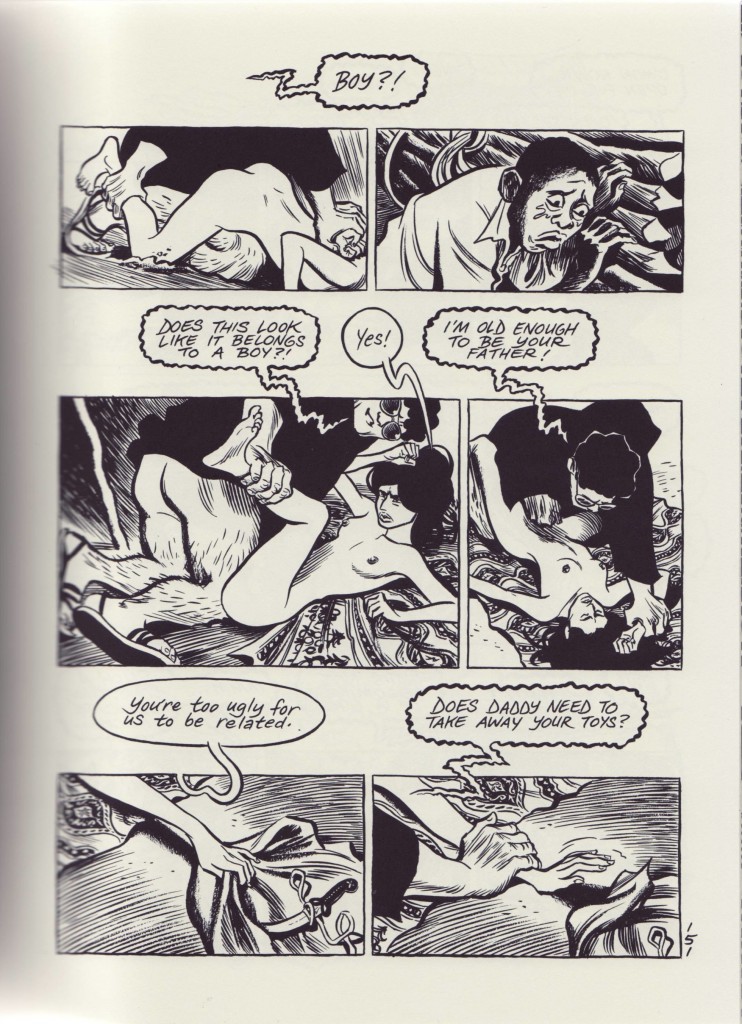

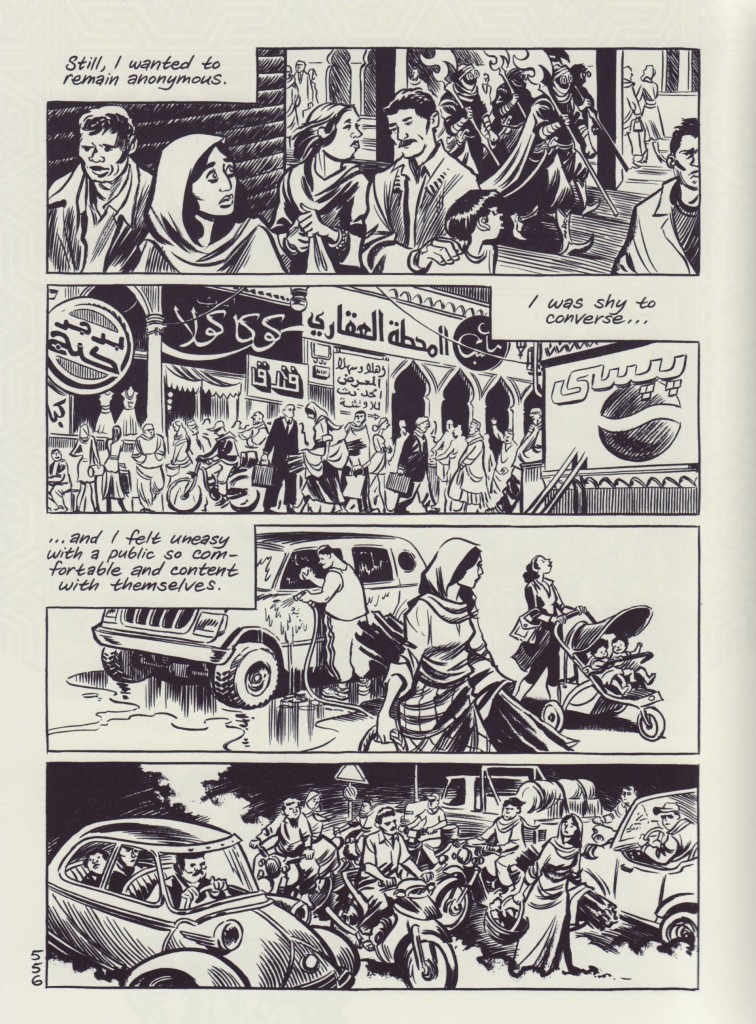

Macan/Kordey

STONE: I wonder–and I wonder this off and on, not just specifically because of our differing levels of enjoyment–how much my engagement with what Macan and Kordey tried for with Soldier X has to do with the fact that I’m more engaged with contemporary super-hero comics than you are, selling them, reading them, just knowing about them. I get a weird, pleasurable reaction off of this, and how much of that is because I know how rare it is to see one that’s drawn well? Hell, just Matt Madden’s colors in those issues he did–I can’t remember seeing a Marvel comic that’s colored that well from the last few years. Some of Dean White’s stuff on the Avengers is quite nice, but that comic has a tendency towards all talk, no show. But for the most part, this is just better looking than the rest of that shit.

NB: Yeah…to get back to your question about the last four issues we read (were those the last four issues of the series? Did Soldier X go on?)…I mean, part of the reason I didn’t really talk about them that much is because the only way to adequately express how horrible they are is to ignore them. It’s not just the badness that gets me…there’s lots of bad art, obviously. I think the Macan/Kordey issues are kind of bad art for most purposes. They’re fairly incoherent, a lot of the ideas are stupid, the good ideas peter out or just sort of sit there thrashing stupidly, like someone hit in the head with a large haddock. That thing with the innocent girl turned cynic for example; it’s kind of funny and kind of creepy, but it’s really rushed and then she’s crying because she’s going to kill her mom — you get, what? A page of her being cynical and creepy and then she’s back to being traumatized little girl again — the pacing is just a mess. I wouldn’t consider that something I’d be excited about reading under normal circumstances.

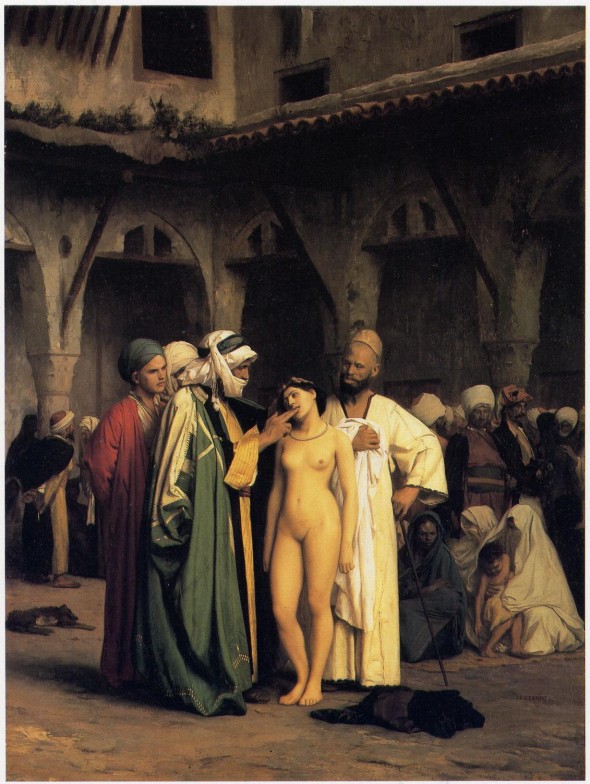

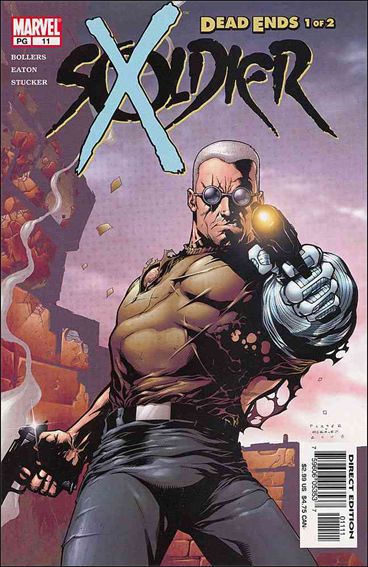

Soldier X #11, Bollers/Eaton/Stucker

But, you compare that to the last four issues of the series and holy shit, Macan and Kordey look like geniuses. The art is just garishly, ridiculously horrible, of course; horrible pacing, anatomy a mess, layout cluttered — but, you know, I expect that from mainstream comics, pretty much. But then the writing is so egregiously pointless. I do get what you were saying about enjoying comics that aren’t trying to be important, and I hear that…but these are comics whose whole purpose appears to be to have Cable wander around more or less aimlessly till the page count runs down. The first two part series (Bollers and Ranson, I guess) is basically just, well this precog foresaw he would meet Cable, and then he does, and he loses his precog ability and kills himself. Which might be fun if there was a hint that anyone involved had figured out that this made a mockery of the whole adventure/superhero format…but no one seems to be in on the joke. It’s all terrorists and this-guy-is-a-deadly-supervillain and overemoting nonsense….

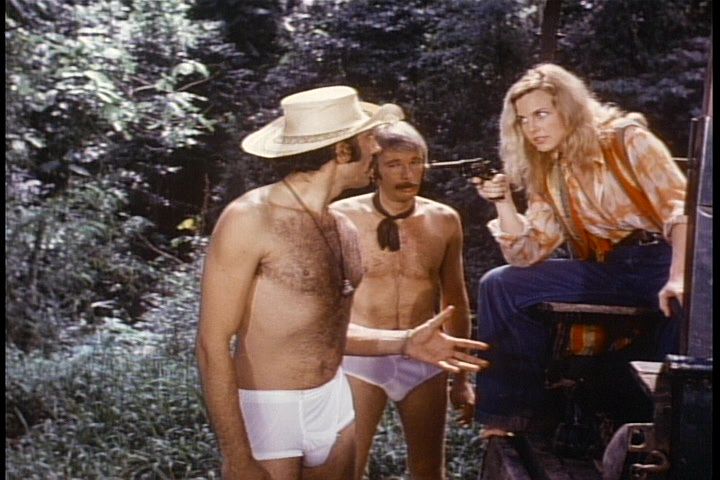

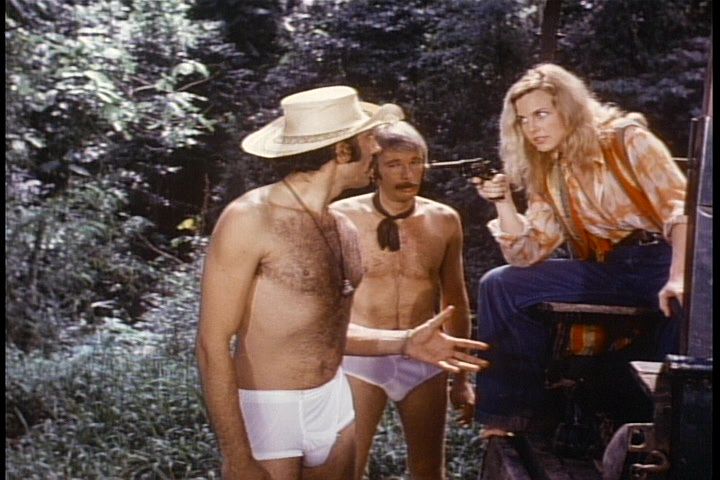

I guess what gets me is really the lack of professionalism; the inability to even deliver the really stupid genre product you’re attempting to deliver. Which is what drives me crazy about mainstream comics in general. Because I really like pulp genre crap, you know? I’ve just been rewatching Jack Hill’s women in prison films, and they’re amazing — shower scene, mudfight scene, torture scene — you’ve got the idiotic, prurient genre trappings, and you work a movie around them that gets in as much of genius and energy and passion as you can. Macan and Kordey were trying to do that, basically — not as successfully as Jack Hill, but they seem to be trying. Whereas Bollers and Ranson and…oh I guess it was still Bollers with different artists — anyway, the point is, these guys don’t even seem to know how their own genre works. I mean, obviously they’ve got a superhero there, but they can’t figure out how to put together a story that is even marginally entertaining as a superhero story. In some ways, I don’t even know if it registers as bad; it’s just a blank. I’d rather look at blank pages. There’s just no reason for these stories to exist.

Still from Jack Hill’s The Big Doll House (1971)

It’s not unlike what I thought about looking at Richard’s review of JL 1. The baseline for publishing a comic just seems to be, “well you’ve got these characters in it. People like these characters. Put that sucker out there.” With women in prison films, you’ve got to at least figure out how to get everyone to the shower scene, but in superhero comics that’s not even a worry; all you need to do is make sure you print the name right on the title, and after that nobody seems to care.

So that’s a long answer to your question which could basically I guess be answered by just saying that Macan and Kordey didn’t wow me, but they clearly have a bare minimum level of competence, and appear to have occasional flashes of brain activity. Bollers writes like…I can’t come up with an analogy. He writes like a bad mainstream comics writer. There isn’t anything more insulting to say.

STONE: I can’t get with women in prison films, but I can see your point. I also totally agree that those final issues of Soldier X (Cable went on to do a buddy comedy comic with Deadpool that lasted for years, I’ve never read it) are fucking terrible, terrible comics. Really out and out stupid, but then again: I’m not sure how much of the blame can be ladled atop Bollers shoulders. Super-hero comics, especially ones made at the bottom (which I’m sure these must have been) get assembled in such a clusterfuck of problems that the blame really has to be shared amongst the tribe of names you see listed next to the word “editor” in the back matter.

I don’t really care to mount a defense of the guy. Those are shitty comics, I agree.

I wonder how much of the problems of things like these are more a reflection of the way they’re made, though. Justice League–I don’t think it’s a good comic, but I also didn’t find myself getting that worked up about it being a bad one, either. It didn’t have enough of a pulse either way to make an impact, there’s just no way on Earth I’ll be able to remember what happened in it. But how could it be good? It has too much to do, too many editorial gaps and story requirements to set up. It’s the base-line of this dumbass publishing initiative, it exists as a comic because you can’t make money off of selling an explanatory brochure.

I need to specify something really quick: earlier, when I said “important”, I think you took that to mean “has something to say”. That’s my fault for not being clear. I don’t want to read super-hero comics like Justice League–super-hero comics that are trying to build franchises or explain super-hero continuity, or basically do anything driven by wider, soap-operatic need. The weird Cable issues I liked–not these, but the ones I mentioned from a few years ago–were just like that. Nothing ever happened in them, the characters just wandered around from place to place, trying to escape one another. Side characters were created, murdered, and that was it. It was totally repetitive, pretty silly, and I loved it. I would totally enjoy a Batman comic where he didn’t do shit, ever. But there’s a fine line between that, and a boring super-hero comic where the characters talk about meeting editorial demands, or each other’s feelings, or whatever else. Ramshackle super-hero comics that are at the bottom of the sales rung, written and drawn by hungry, work-craving freaks. Those interest me.

NB: That’s fair enough about Bollers; I find it difficult to believe he could do anything I liked after reading those issues, but people do often do their absolute worst work for the mainstream — there’s no reason he couldn’t have done something significantly better than those four comics.

Also, just to be clear…there are many, many horrible women in prison films. Incoherent, rambling messes of movies; poorly constructed tottering scaffoldings on which indifferent slabs of incompetent sleaze are dumped more or less at random.

I guess the thing I would say about even the worst of them, though, is…I sort of understand what they’re trying to do. That is, you make a women in prison film, you’re aiming for prurient interest on a low budget. They’re kind of obsolete now that the internet has blessed us with infinite porn…but the result of that has been that they’ve largely disappeared. There was this demand, and these things met this demand, sometimes with skill and verve, like in Jack Hill’s films, and sometimes with utter incompetence and wretched stupidity. But competent or incompetent, I understand where they’re coming from.

But the Bollers stuff is baffling. Why would you want to write that? This is true for the Macan/Kordey books too, to some extent. Wanting to see T&A I get. James Bond I get. Twilight I get. Superman, Batman, Wonder Woman, Spider-Man, Sailor Moon, Harry Potter, Ben Ten, even the X-Men — I don’t necessarily love or even like all those things, but I understand what’s happening. But Cable? You have to write a story in which Cable does godlike things, mutters about his incomprehensible backstory, and whines? Who wants to read that? What’s wrong with them? What the hell?

I sort of wonder if that ties into what you said in one of your posts:

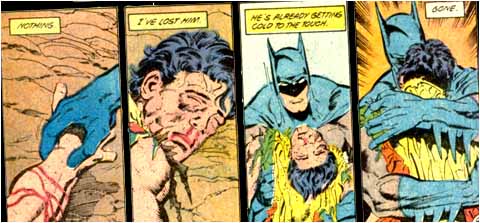

“I doubt whether the color selections had any specific meaning, but doesn’t it add a certain layer of…not seriousness, not maturity, but a certain adultness to the material? You know, that sort of fake adultness that super-hero comics still, even now, does better than iCarly or Big Time Rush? Maybe it’s just me. I doubt it, that I’m the only one who still gets a bit jacked in when super-hero comics play at being grown-up and serious in ways beyond somebody cutting the Joker’s face off and hanging it on a wall while the Joker makes a joke about how said torture made him cum. (That example is from a comic that was released today.) It’s that feeling, the one you get when fake-Thing realizes what friendship can mean in “This Man, This Monster”, or what Bruce Wayne’s say when he shakes his fist at his empty costume in “Death in the Family”, that feeling that has nothing to do with being a real grown-up but still encompasses what you thought being a grown-up meant.”

I think it’s interesting that the first in that list is a Lee/Kirby story, because Lee/Kirby is arguably when comics started really being aimed at an audience that was older — 15 year olds, maybe, rather than 8 year olds. Now, though…who was reading those Cable comics? Not 8 year olds; probably not 15 year olds; these are early 2000s, right, which means that the audience for them is probably thirtysomethings. So really, if the comics are about the allure of adulthood, it’s not about imagining what you thought being a grown-up meant so much as about being a grown-up imagining being a kid imagining what being a grown-up meant.

That sort of sounds like Lacan actually: for Lacan your self-image is always a mistake, a kind of misreflection. And actually he sees it especially in infants mistaking their image for being older than it is; the child sees itself and thinks it’s grown up and is euphoric. You could see mainstream comics as maybe a way for adults to try to go back and recapture that; trying to remember what it was like to have mistaken themselves for adults. That works with Cable too; this weird cobbled-together cyborg going back into the past to reimagine the future.

I guess the result of that is that the nerd-knowledge itself, the fact that the character makes no sense except to the initiated, ends up being the draw; to see yourself in Cable is to see yourself as a time-lost master of nostalgia-fu; the imaginary grown-up is a joyfully integrated comics consumer…..

STONE: The answer to your Bollers question is this: Marvel knew the comic was getting cancelled, and they brought on Bollers to keep the Cable money coming in until the next version of the series was ready to launch. And Bollers probably agreed to take on what amounts to a thankless task simply because he wanted to get his foot in the door, he wanted to have the note “is a good employee who will take one for the team” attached to his name when editors were looking for better, plusher gigs. It’s the same reason anybody does something for these companies–so they can do more stuff for these companies, and maybe that “more” might include something they’ll have more control over. I don’t believe there’s anything else to it.

I’m trying to find a way to combat some of what you’re saying, but I don’t know that I really can. I think there’s definitely some accuracy to the idea you’re describing at the end there, that part of the attraction to Cable (or other needlessly complicated super-hero characters) is the needless complication itself, the inherent difficulty and time-expenditure that it might have once required. (Obviously, wikipedia and digital piracy remove all difficulty from the “learning about Cable” hobby.) But that presupposes the idea that satisfaction can be automatically found in “mastering” nostalgic super-hero information, and I think that requires a certain set of personality quirks to be true–and obviously, not everyone who gets into Cable and enjoys Cable comics is necessarily going to have the same type of personality.

I really have a hard time answering to the question “what these are trying to do”, because I’m honestly no longer sure that the answer isn’t a hard line “absolutely nothing”. They’re the back side of trading cards expanded to 22 pages, and the only purpose of a trading card is to be bought and sold, and that makes super-hero comics…you see what I mean? At the same time, I do think that answer is inherently problematic and hole-pokable, because it’s obvious to me that there’s a lot of pleasure found in certain strands of super-hero comics if the person is a fan of extended, serial soap opera stuff, because there’s some of them that clearly still do that. (The X-Men are a prime example, I think, although I’ve had at least one conversation about the various women Bruce Wayne dated to know that DC did used to know how to get that right too.)

I’m not sure if the passage you quoted has a lot of connection here, although there’s a bit of willfull obtuseness on my part that might prevent me from spotting it anyway. Generally, I just wanted to acknowledge that the way those covers were colored jumped out at me as being a blatant sign of Kordey behaving as an artist when the product itself–and the environment it was produced in–would have been just as content for him to behave more like a product designer, a maker of widgets, an industrial supplier. Those moments are the sort of reminders I’m starving to find when I come to this stuff, the sense that the people involved are doing something that’s just beyond what’s being asked of them, and the gamble is paying off. Starlin and Aparo spent quite a few pages in Death in the Family failing to make it clear exactly what Bruce Wayne was going through, except for the part where they succeeded, and that success is what sticks in my memory. It’s the proof that somebody was trying, maybe? That makes more sense than “adult”. No big deal though, it got you to bring up that Lacan stuff. Worked out for the best.

Steranko/Aparo, “A Death in the Family”

NB: Yeah…not sure anyone else is ever really happy to have me bring up Lacan.

I will stop talking about him in a moment…but I should maybe point out just briefly that as far as I understand it, Lacan doesn’t like anything having to do with the imaginary. Presuming you were able to create some sort of alternate reality where you could resurrect him and force him to read large swathes of popular culture, it seems extremely unlikely that he would distinguish between Cable comics and, say, Harry Potter…or maybe even Jane Austen. It’s all false reflections in the mirror.

But! Leaving the dead phallus guy aside for the moment; it’s absolutely true that there’s some sense in which Bollers is doing what he’s doing for money, period. The thing is, though…the same is true of Mariah Carey, or Jack Hill, or Janet Evanovich, or tons of manga (all the BL titles kinukitty reviews, for example.) Pulp crap is pulp crap…but that isn’t quite the same as an explanation, I don’t think. Even if it’s just a machine grinding out product — why that product? Why do people want to see this, or, at least, why do the creators think people want to see this? Why does Marvel think people want to read a Cable story where a mutant sacrifices herself in order to show that mutants aren’t above the law while Cable fights giant dogs in her head? Like I said, I can understand the appeal of a lot of pop culture crap which is made for money; with superhero comics, I have real trouble.

I do sometimes wonder (and you kind of say this in your last response) whether part of the appeal for some readers isn’t the abject awfulness; the stuff is so bad, that there’s a charge in seeing glimmers of competence; in watching folks like Macan and Kordey take this totally bullshit concept that nobody could possibly care about and cobbling together a couple of moments of meaningful narrative out of it.

There’s something of that in exploitation film too — the scrappiness of the filmmaking, the

often rudimentary acting, the glommed together costumes, the patchwork scripts — there’s this kind of corporatist punk rock aesthetic, this naked, desperate scramble for cash which gives the moments of beauty or genius a kind of gutter purity. That’s definitely a feature rather than a bug if you like those films; “Friday the 13th” or “I Spit on Your Grave” with high gloss production values and Shakespearian actors would be worse movies, not better ones. Getting rid of the exploitation in exploitation gives you a more pretentious movie, not necessarily a better one.

For me, I just feel like superhero comics are in general bad by those standards; like the moments when somebody manages to do something interesting with the corporate dictats are fewer and farther between than in exploitation film or post-disco pop. Britney Spears or Macan and Kordey — I mean, that’s not even close. I like Macan and Kordey okay, but Britney has been making bizarre, sublime robotic confections for a decade now.

Do you strongly disagree with that? Would you make the argument Macan/Kordey > Friday the 13th? or >Britney? Or is it the fact that it’s worse that in some ways is the appeal; that there’s so little gold in mainstream superhero comics that each little bit of it is all the more precious?

STONE: I don’t know, Noah. From where I sit right now, I enjoyed what Macan and Kordey brought to the table…I don’t have a gauge on whether that was a higher level or a lower level of pleasure, just that it existed. Matt Seneca’s recent writing on the Justice League makes a great case for the lack of depth that most super-hero comics usually have to offer, to say nothing of their various artistic failings. Soldier X was trying to do something interesting, it wasn’t just trying to do something different–different is easy in super-hero comics, they shoot outside the box so rarely, they’ve followed the same patterns for so long–but interesting is really rare, it’s harder. Craftsmanship–which I think Kordey had, and has, when he’s not working at the pace that Soldier X demanded–is just as rare.

I know that I’m not being fair, by the way. I’m giving credit to my imagined, idealistic version of what I think these guys were doing. But I look at where they are now–all of them are gone from Marvel, with some measure of dignity and integrity still intact–and I can’t not be impressed by the sight of it.

You’re right about what would happen to Friday the 13th and I Spit On Your Grave if they were “made better”, but I don’t know that I can participate in the compare/contrast in the way you seem to be doing there. For one, I dislike both of those particular movies in every iteration, I’d just rather watch Spooks, or another one of those slick Korean crime thrillers that keeps getting churned out. But for the other, I just don’t have it in me (today, I could totally have it in me tomorrow) to claim Roz Meyers hanging bankers > Igor Kordey drawing slaughter in a 9-panel grid. My brain isn’t firing in that direction right now.

I totally agree that the moments when corporate hero comics “get it right” are fiendishly rare. I wonder though–how much of that is due to the thing that people like Alan Moore and Jodorowsky have been recommending for so long? How much of it is because the people who once would have been stuck churning out awesomeness can go somewhere else, and do something better? I don’t know if you’ve read things like Hellboy or BPRD, things like Bone or Amulet or Usagi Yojimbo or, really, whatever, competent, creepy shit like Locke and Key, but how, if you’re a halfway intelligent cartoonist with something interesting to say, do you end up doing what guys like Jim Aparo (who you know I love) did? You’d have to be fucking crazy to sit around and draw or write super-hero comics for any length of time that doesn’t exactly equal however much you HAVE to do it, to get something else going. Mike Mignola, Jeff Smith, Stan Sakai–those guys could do a pretty cool Batman comic, I’m sure. But why the fuck would they ever do that? Why would anybody who doesn’t have to? How is that not the ambition of something with no ambition whatsoever? It would be like Vince Gilligan giving up on Breaking Bad so he can write episodes of CSI Miami.

I know I haven’t covered your Britney question, but that’s okay with me. I’ll leave that one for next time.

NB: Nobody wants to talk Britney, damn it. I love that picture of her I posted above where she’s got no hair. I think it’s the only picture of her where she looks happy and cute rather than kind of vapidly terrifying. She somehow seems most herself when she’s a mannequin.

Is it embarrassing if I admit I’d never heard of Jodorowsky?

Anyway, I don’t disagree with you; I think it can maybe be summed up by saying that it’s a serious problem when a popular genre loses its audience but somehow keeps generating product anyway. It’s not a good situation to be in aesthetically.

Maybe to end I should just say that, though I didn’t love or even quite like these comics, I have respect for Macan and Kordey and what they were trying to do. They wanted to make good comics, and I think had the ability to make good comics; it just wasn’t really a time or a place or a venue where good comics were a possibility, I don’t think. I’d certainly look at work by either of them again (which wasn’t something I was saying about Steve Gerber after I read Man-Thing.) I wish I’d been able to read the story they wanted to tell here, too. That’s comics, though, I guess.