Megan Purdy hosted a Blog Carnival on Censure vs. Censor over at Women Write About Comics. I thought I’d mirror the organizational post here with links and such (as you’ll see, Kim O’Connor and I both contributed here at HU.)

The mirrored post is below.

_________

by Megan Purdy

Welcome back to WWAC’s irregular blog carnival! It’s been awhile. This time we teamed up with Hooded Utilitarian, Paper Droids, Panels, Comics Spire, and Deadshirt to talk about censorship. Here’s the question I put to our brave writers:

Censors and censures: What’s the difference? What is the social utility, if any, of them? What to do about the strange reaction to criticism of comics, where it’s all perceived as threatening, even post-Code, with Frederic Wertham invoked at every turn? Why are so many people so defensive, so Team Comics, about a medium that’s enjoying a creative renaissance?

Throughout the day, our partners have been publishing their responses. Here now, are all of them collected:

The Effect of Living Backwards, by Kim O’Connor at Hooded Utilitarian

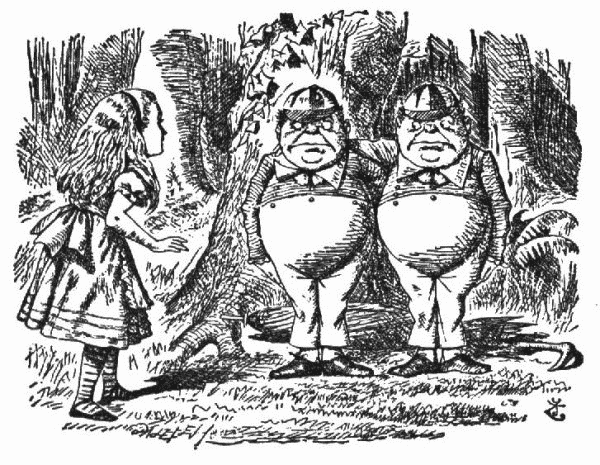

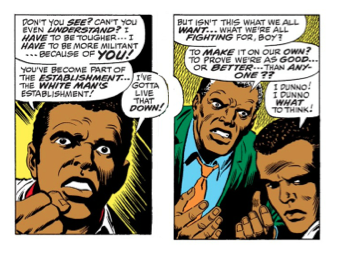

And yet, censorship is an accusation frequently hurled at “politically correct” liberal-leaning members of the comics community. The accusers are, like, Tinfoil Hat Bulbasaur, sometimes even using words like self-censorship and thought police to describe what most of us would call a conscience. We’re through the looking glass, where the people with the most power and the loudest voices are the ones who worry most about being silenced. Potent industry figures like Gary Groth are waging an imaginary war against opponents (“opponents”) who have no actual interest in stripping artists of their freedom of speech. So let me say it once, loud and clear for all the turkeys in the back: Expressing an opinion—even a harsh one—is not equivalent to arguing for censorship. It’s not even close.

Censoring the World: The Fight to Protect the Innocence of Children, by KM Bezner at Women Write About Comics

Parents want to protect their children. This isn’t a groundbreaking revelation or a new development, and of course is completely understandable. But it’s impossible to censor the world. Restricting their access to books can not only suppress a love of reading, it can also discourage them from seeking out answers to the questions they will inevitably have about sex, racism, religion, and violence. It’s important to remember that challenging a book is a decision that will impact children other than your own.

Diversity: There’s Plenty of Room in the Sandbox, by Swapna Krishna at Panels

It’s a great time to be a comics fan. The industry is enjoying such an amazing renaissance, with diverse titles releasing left and right. More people are getting into comics, are interested in exploring and trying the medium for the first time. With an increasing emphasis on diversity comes increased sales and a larger audience. This should be a good thing. Why, then, are so many people defensive about the way things were? Why are so many fans resistant to these changes?

A Superstitious and Cowardly Lot: Sexism, “Free Speech,” and Comics Fandom, by Joe Stando at Deadshirt

Among these tricks are clothing their harassment in progressive buzzwords. Free speech is good, right? And censorship is bad. This is America, after all. So even the most sexist remarks by creators, the most offensive artwork and the most prolonged harassment must be good, since they’re “free speech.” Similarly, anytime someone criticizes said speech, it must be censorship, because that’s the opposite, right?

My Problematic Faves: On Censureship and Self-Censorship in Comics, by Allison O’Toole, at Paper Droids.

We all enjoy stories that unintentionally do things wrong at times, but everyone has a different threshold for the kind of problematic content they can overlook. Personally, I think mine has something to do with other redeeming qualities in a comic. I believe it’s possible to point out that any story–comic, novel, movie, TV show, etc.–is deeply problematic while acknowledging that it has other strengths, and it’s up to each reader to decide whether they want to engage with that particular work or not.

The Morality of Free Speech, or Lack Thereof, by Noah Berlatsky at Hooded Utilitarian

For many who identify as comics fans, or as art fans, or as libertarians, or as some intersection of all those things, this may seem like heresy. Supporting free speech is often touted as a kind of iconic sign of open-mindedness; a stand against the philistines. Alternately, or in addition, to be against free speech is seen as supporting tyranny and that mighty argument-quashing shibboleth, Big Brother.

The Fightin’ Fans Vs. the Censorious Critics, by Steve Morris at The Spire

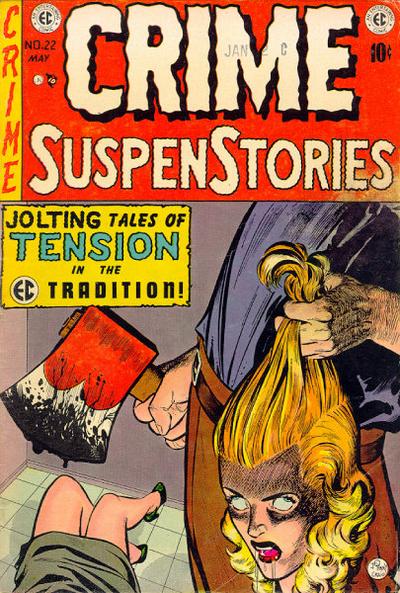

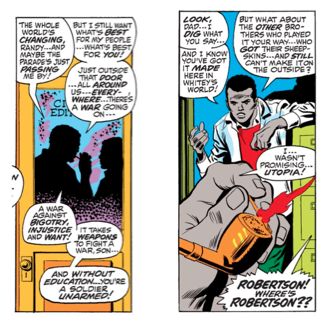

‘Mainstream’ comics, as they’re called for some reason, have been trained to react defensively to any new challenge – since Wertham managed to restrict the medium, fans and authors have wanted to prove that nothing will ever hold them back again. This led to some comics which went way over the line in their approach, and it also led to some of the strongest work in the medium. Right now, though, the comics themselves are being overshadowed by the people who’re buying them.